Underwater Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plymouth Shipwrecks Commercial Diving in Spain

INTERNATIONAL DIVING SCHOOLS ASSOCIATION EDITION NO.26 JULY 2015 PLYMOUTH SHIPWRECKS COMMERCIAL DIVING IN SPAIN DEVELOPMENTS IN SICILIAN LAW THE ANNUAL MEETING Cygnus DIVE Underwater Wrist-Mountable Ultrasonic Thickness Gauge Wrist-mountable Large bright AMOLED display Measures through coatings On-board data logging capability Topside monitoring with measurements video overlayed Twin crystal probe option for extreme corrosion and anchor chains t: +44 (0)1305 265533 e: [email protected] w: www.cygnus-instruments.com Page 3 FROM THE Editors: Alan Bax and Jill Williams CHAIRMAN Art Editor: Michael Norriss International Diving Schools Association 47 Faubourg de la Madeleine 56140 MALESTROIT FRANCE Phone: +33 (0)2 9773 7261 e-mail: [email protected] web: Dear Members www.idsaworldwide.org F irst may I welcome the Aegean Diving Services as an Associate Member. Another year has gone by, and we are again looking at the Annual Meeting, this year teaching Level 1 and increased in Cork where our hosts – the through Level 2, 3 & 4 ? Irish Naval Diving Section – are offering a very warm welcome, ••Obtaining an ISO Approval both professionally and socially. ••Liaison with other organisa- It looks to be an interesting tions meeting and currently the Board Several of these items might is considering the following items affect the future shape and for the Agenda: operations of the Association, A Commercial Diving Instruc- •• therefore we would very much like tor Qualification to receive comments on these ••The need for an IDSA Diver items, fresh suggestions will be Training Manual most welcome, as will ideas for ••The revision of the Level 2 presentations - I am sure many Standard to include the use of members to know that Rory mixed gases in Inland /Inshore Golden has agreed to recount his Operations. -

The Muddy Puddle :

WWW.CroydonBsac.Com . : : : : : : The Muddy Puddle : : Upcoming dives May 2008 Issue 2 for 2008 Easter Plymouth What kind of people do we attract?? 24-26 Falmouth weekend May You may think earer El Presidente, as singing all dancing must that the club attracts a well as other named 31st Oceana 25m have toy it is now, it was fairly varied type of peo- members and ex- a collection of text May ple from all walks of like members of the club, pages for computer who are primarily inter- plus the usual learn to geeks, but now every- 14th Kerryado 42m ested in Diving. dive, London dive clubs one and everything must June We all dress up etc searches criteria. have a webpage, and as in rubber at weekend, 21st Littlehampton 35m we all know the club has However, some some of us in skin tight june max a website detailing the are into the more rubber (Shouldn’t be al- activities, history and ‘Westward Bound’ cate- lowed for some) but most 27-5th Scapa Flow characters from the gory of searches, which of us in expensive bin- July club. would lead a casual ob- liners, but we seem to be server to believe the 6th July Ramsgarth 25m However, in re- attracting some attention club is more an extreme cent months the website of a different kind. ‘swinger’ type of club has been picked up on The public face and the only diving we 12-13 Ioleanthe(40m) & some strange searches. of the club has moved on do does not require July Salsette (45m) Our webmaster collects over the past few years weight belts. -

Seattle 2015

Peripheries and Boundaries SEATTLE 2015 48th Annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology January 6-11, 2015 Seattle, Washington CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS (Our conference logo, "Peripheries and Boundaries," by Coast Salish artist lessLIE) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 01 – Symposium Abstracts Page 13 – General Sessions Page 16 – Forum/Panel Abstracts Page 24 – Paper and Poster Abstracts (All listings include room and session time information) SYMPOSIUM ABSTRACTS [SYM-01] The Multicultural Caribbean and Its Overlooked Histories Chairs: Shea Henry (Simon Fraser University), Alexis K Ohman (College of William and Mary) Discussants: Krysta Ryzewski (Wayne State University) Many recent historical archaeological investigations in the Caribbean have explored the peoples and cultures that have been largely overlooked. The historical era of the Caribbean has seen the decline and introduction of various different and opposing cultures. Because of this, the cultural landscape of the Caribbean today is one of the most diverse in the world. However, some of these cultures have been more extensively explored archaeologically than others. A few of the areas of study that have begun to receive more attention in recent years are contact era interaction, indentured labor populations, historical environment and landscape, re-excavation of colonial sites with new discoveries and interpretations, and other aspects of daily life in the colonial Caribbean. This symposium seeks to explore new areas of overlooked peoples, cultures, and activities that have -

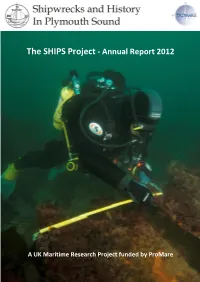

Annual Report 2012

The SHIPS Project - Annual Report 2012 A UK Maritime Research Project funded by ProMare 1 SHIPS Project Report 2012 ProMare President and Chief Archaeologist Dr. Ayse Atauz Phaneuf Project Manager Peter Holt Foreword The SHIPS Project has a long history of exploring Plymouth Sound, and ProMare began to support these efforts in 2010 by increasing the fieldwork activities as well as reaching research and outreach objectives. 2012 was the first year that we have concentrated our efforts in investigating promising underwater targets identified during previous geophysical surveys. We have had a very productive season as a result, and the contributions that our 2012 season’s work has made are summarized in this document. SHIPS can best be described as a community project, and the large team of divers, researchers, archaeologists, historians, finds experts, illustrators and naval architects associated with the project continue their efforts in processing the information and data that has been collected throughout the year. These local volunteers are often joined by archaeology students from the universities in Exeter, Bristol and Oxford, as well as hydrography and environmental science students at Plymouth University. Local commercial organisations, sports diving clubs and survey companies such as Swathe Services Ltd. and Sonardyne International Ltd. support the project, particularly by helping us create detailed maps of the seabed and important archaeological sites. I would like to say a big ‘thank you’ to all the people who have helped us this year, we could not do it without you. Dr. Ayse Atauz Phaneuf ProMare President and Chief Archaeologist ProMare Established in 2001 to promote marine research and exploration throughout the world, ProMare is a non-profit corporation and public charity, 501(c)(3). -

“T I T a N I C 3 D”

“T I T A N I C 3 D” “Titanic was called the Ship of Dreams. And it was. It really was...” In 1997, James Cameron’s TITANIC set sail in theaters -- and one of the world’s most breathtaking and timeless love stories was born. The film’s journey became an international phenomenon as vast as its name, garnering a record number of Academy Award® nominations, 11 Academy Awards® and grossing over $1.8 billion worldwide. On April 6th, 2012, precisely a century after the historic ship’s sinking and 15 years after the film’s initial theatrical release, TITANIC resurfaces in theaters in state-of-the-art 3D. Upon its original release, TITANIC was celebrated for transporting audiences back in time, right into the belly of the R.M.S Titanic in all her glory and into the heart of a forbidden love affair entwined with the ship’s epic collision with human arrogance, nature and fate. Now, the leading edge of 3D conversion technology has allowed Oscar® winning director James Cameron to bring moviegoers the most visceral and dynamic screen experience of TITANIC yet imagined. The artistic process of re-visualizing TITANIC in three dimensions was overseen entirely by Cameron himself, along with his long-time producing partner Jon Landau – who both pushed the conversion company Stereo D literally to unprecedented visual breadth. Cameron guided them to use the latest visual tools not only to intensify the film’s sweeping race for survival, but to reveal the power of 3D to make the film’s most stirring emotions even more personal. -

RNLI Services 1945

Services by the Life-boats of the Institution, by Shore-boats and by Auxiliary Rescue- boats during 1945 During the year life-boats were launched 497 times. Of these launches 118 were to vessels and aeroplanes in distress through attack by the enemy or from other causes due to the war. The Record Month by Month Vessels Lives Number Lives which Lives Rescued of Rescued Life-boats Rescued by 1945 Life-boat by Saved or by Auxiliary Launches Life-boats Helped Shore-boats Rescue- to Save boats January . 63 100 6 4 - February . 53 22 6 5 - March . 43 45 5 10 - April . 41 56 18 1 7 May* . 26 25 2 4 - June . 28 80 3 26 - July . 40 24 6 14 - August . 39 13 7 - - September . 36 49 6 30 - October . 50 116 4 10 - November . 28 - - 22 - December . 50 23 2 1 - Totals . 497 553 65 127 7 * The war ended on the last minute of the eighth of May I Three Medals for Gallantry ANGLE, PEMBROKESHIRE On the 16th July, 1945, the Angle life-boat rescued nine of the crew of the S.S. Walter L. M. Russ. COXSWAIN JAMES WATKINS was awarded a clasp to his bronze medal. ST. IVES, CORNWALL On the 24th October, 1945, the St. Ives life-boat rescued two persons from the ketch Minnie Flossie, of Bideford. COXSWAIN WILLIAM PETERS was awarded the silver medal. WALTON AND FRINTON, ESSEX On the 21st December, 1945, the Walton and Frinton life-boat rescued the crew of five naval ratings of the motor fishing vessel No. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, January 30, 2012 1:44:57PM School: Firelands Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 46618 EN Cats! Brimner, Larry Dane LG 0.3 0.5 49 F 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 31584 EN Big Brown Bear McPhail, David LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 84997 EN Colors and the Number 1 Sargent, Daina LG 0.4 0.5 81 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor LG 0.5 0.5 77 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 31858 EN Hop, Skip, Run Leonard, Marcia LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 26922 EN Hot Rod Harry Petrie, Catherine LG 0.5 0.5 63 F 69269 EN My Best Friend Hall, Kirsten LG 0.5 0.5 91 F 60939 EN Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 26927 EN Bubble Trouble Hulme, Joy N. -

'Liberty'cargo Ship

‘LIBERTY’ CARGO SHIP FEATURE ARTICLE written by James Davies for KEY INFORMATION Country of Origin: United States of America Manufacturers: Alabama Dry Dock Co, Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards Inc, California Shipbuilding Corp, Delta Shipbuilding Co, J A Jones Construction Co (Brunswick), J A Jones Construction Co (Panama City), Kaiser Co, Marinship Corp, New England Shipbuilding Corp, North Carolina Shipbuilding Co, Oregon Shipbuilding Corp, Permanente Metals Co, St Johns River Shipbuilding Co, Southeastern Shipbuilding Corp, Todd Houston Shipbuilding Corp, Walsh-Kaiser Co. Major Variants: General cargo, tanker, collier, (modifications also boxed aircraft transport, tank transport, hospital ship, troopship). Role: Cargo transport, troop transport, hospital ship, repair ship. Operated by: United States of America, Great Britain, (small quantity also Norway, Belgium, Soviet Union, France, Greece, Netherlands and other nations). First Laid Down: 30th April 1941 Last Completed: 30th October 1945 Units: 2,711 ships laid down, 2,710 entered service. Released by WW2Ships.com USA OTHER SHIPS www.WW2Ships.com FEATURE ARTICLE 'Liberty' Cargo Ship © James Davies Contents CONTENTS ‘Liberty’ Cargo Ship ...............................................................................................................1 Key Information .......................................................................................................................1 Contents.....................................................................................................................................2 -

Hollywood Places Biggest 3-D Bet Yet on 'Avatar'

Hollywood Places Biggest 3-D Bet Yet on 'Avatar' By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Published: July 24, 2009 Filed at 12:44 p.m. ET SAN DIEGO (AP) -- When James Cameron directed his first 3-D film, ''Terminator 2: 3-D,'' for Universal Studios theme parks more than a decade ago, the bulky camera equipment made some shots awkward or impossible. The 450-pound contraption -- which had two film cameras mounted on a metal frame -- was so heavy that producers had to jury-rig construction equipment to lift it off the ground for shots from above. The cameras, slightly set apart, had to be mechanically pointed together at the subject, then locked into place like an unwieldy set of eyes to help create the 3-D effect. At $60 million, the 12-minute film was the most expensive frame-for-frame production ever. Now, five months from its release, Cameron's ''Avatar,'' the first feature film he has directed since ''Titanic'' (1997), promises to take 3-D cinematography to an unrivaled level, using a more nimble 3-D camera system that he helped invent. Cameron's heavily hyped return also marks Hollywood's biggest bet yet that 3-D can bolster box office returns. News Corp.'s 20th Century Fox has budgeted $237 million for the production alone of ''Avatar.'' The movie uses digital 3-D technology, which requires audience members to wear polarized glasses. It is a vast improvement on the sometimes headache-inducing techniques that relied on cardboard cutout glasses with red and green lenses and rose and fell in popularity in the 1950s. -

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

MC Quizlist Embed Port US Ltr

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, January 30, 2012 1:44:04PM School: Firelands Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 77402 EN 10 Best Things About My Dad, The Loomis, Christine LG 2.1 0.5 244 F 103833 EN 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric LG 2.4 0.5 404 F 64468 EN 100 Monsters in My School Bader, Bonnie LG 2.4 0.5 1,304 F 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf LG 1.4 0.5 189 F 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Buller, Jon LG 2.5 0.5 1,121 F Sea 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon MG 3.8 1.0 10,043 F 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie LG 4.4 1.0 6,737 NF 140211 EN 3 Little Dassies, The Brett, Jan LG 3.7 0.5 893 F 121986 EN 42 Miles Zimmer, Tracie Vaughn MG 5.8 1.0 5,067 F 128693 EN 4x4 Trucks Von Finn, Denny MG 3.9 0.5 576 NF 1551 EN Aaron Copland Venezia, Mike LG 5.5 0.5 1,436 NF 19346 EN Abby's Lucky Thirteen Martin, Ann M. MG 4.9 4.0 24,399 F 17601 EN Abe Lincoln: Log Cabin to White North, Sterling MG 8.4 4.0 24,236 NF House 45400 EN Abe Lincoln Remembers Turner, Ann LG 4.1 0.5 738 F 127685 EN Abe's Honest Words Rappaport, Doreen LG 4.9 0.5 1,367 NF 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William MG 5.9 3.0 17,610 F 127405 EN Abigail Breslin Tieck, Sarah LG 3.9 0.5 1,024 NF 39787 EN Abigail Takes the Wheel Avi LG 2.9 0.5 1,960 F 86635 EN Abominable Snowman Doesn't Dadey, Debbie LG 4.0 1.0 6,644 F Roast Marshmallows, The 74824 EN Abraham Lincoln Knox, Barbara LG 2.1 0.5 214 NF 42301 EN Abraham Lincoln (United States Welsbacher, Anne MG