John L. Sublett (Part 1 of 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorandum Board of Supervisors

MEMORANDUM OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY OF PLACER TO: Honorable Board of Supervisors FROM: Jennifer Montgomery Supervisor, District 5 DATE: October 9,2012 SUBJECT: RESOLUTION - Adopt and present a Resolution to Clarence Emil "Bud" Anderson for his outstanding service to his country and his community. ACTION REQUESTED Adopt and present a Resolution to Clarence Emil "Bud" Anderson for his outstanding service to his country and his community. BACKGROUND Colonel Anderson has over thirty years of military service, and was a test pilot at Wright Field where he also served as Chief of Fighter Operations. He also served at Edwards Air Force Base where he was Chief of Flight Test Operations and Deputy Director of Flight Test. Colonel Anderson served two tours at The Pentagon and commanded three fighter organizations. From June to December 1970, he commanded the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, an F-105 Thunderchief unit, during its final months of service in the Vietnam War, and retired in March 1972. He was decorated twenty-five times for his service to the United States. After his retirement from active duty as a Colonel, he became the manager of the McDonnell Aircraft Company's Flight Test Facility at Edwards AFB, serving there until 1998. During his career, he flew over 100 types of aircraft, and logged over 7,000 hours. Anderson is possibly best known for his close friendship with General Chuck Yeager from World War II, where both served in the 35th Fighter Group, to the present. Yeager once called him "The best fighter pilot I ever saw". -

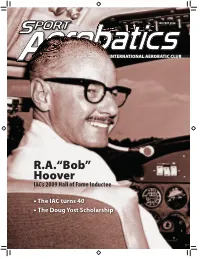

“Bob” Hoover IAC’S 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee

JANUARY 2010 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF TTHEHE INTERNATIONALI AEROBATIC CLUB R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee • The IAC turns 40 • The Doug Yost Scholarship PLATINUM SPONSORS Northwest Insurance Group/Berkley Aviation Sherman Chamber of Commerce GOLD SPONSORS Aviat Aircraft Inc. The IAC wishes to thank Denison Chamber of Commerce MT Propeller GmbH the individual and MX Aircraft corporate sponsors Southeast Aero Services/Extra Aircraft of the SILVER SPONSORS David and Martha Martin 2009 National Aerobatic Jim Kimball Enterprises Norm DeWitt Championships. Rhodes Real Estate Vaughn Electric BRONZE SPONSORS ASL Camguard Bill Marcellus Digital Solutions IAC Chapter 3 IAC Chapter 19 IAC Chapter 52 Lake Texoma Jet Center Lee Olmstead Andy Olmstead Joe Rushing Mike Plyler Texoma Living! Magazine Laurie Zaleski JANUARY 2010 • VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 1 • IAC SPORT AEROBATICS CONTENTS FEATURES 6 R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee – Reggie Paulk 14 Training Notes Doug Yost Scholarship – Lise Lemeland 18 40 Years Ago . The IAC comes to life – Phil Norton COLUMNS 6 3 President’s Page – Doug Bartlett 28 Just for Starters – Greg Koontz 32 Safety Corner – Stan Burks DEPARTMENTS 14 2 Letter from the Editor 4 Newsbriefs 30 IAC Merchandise 31 Fly Mart & Classifieds THE COVER IAC Hall of Famer R. A. “Bob” Hoover at the controls of his Shrike Commander. 18 – Photo: EAA Photo Archives LETTER from the EDITOR OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Doug Bartlett by Reggie Paulk IAC Manager: Trish Deimer Editor: Reggie Paulk Senior Art Director: Phil Norton Interim Dir. of Publications: Mary Jones Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh Contributing Authors: Doug Bartlett Lise Lemeland Stan Burks Phil Norton Greg Koontz Reggie Paulk IAC Correspondence International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

“One of the World's Best Air Shows” Coming to Goldsboro, NC Seymour

For Immediate Release “One of the world’s best air shows” coming to Goldsboro, NC USAF Thunderbirds – Courtesy Staff Sgt Richard Rose Jr. Seymour Johnson AFB – Goldsboro, NC – “Wings Over Wayne is one of the world’s best air shows,” said Chuck Allen, Mayor of Goldsboro. “Seymour Johnson does a phenomenal job attracting the best lineup of airpower and performers, alongside the F-15E Strike Eagle and KC-135 aircraft already stationed at the base.” Located in Goldsboro, the seat of Wayne County, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base will stage and choreograph the Wings Over Wayne Air Show on Saturday and Sunday, April 27-28. Headlining the exhibition from Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, is the premier Air Force jet demonstration team, the Thunderbirds. The gates open each day at 9 AM, with aerial displays from 11 AM until 4:30 PM. “As our guests, you will be able to see world-class acrobatics and ground demonstrations that are truly a sight to be seen,” said Colonel Donn Yates, Commander of Seymour Johnson’s 4thFighter Wing. “Some of the performers scheduled include the F- 35 Demonstration Team, Tora! Tora! Tora!, the US Army Black Daggers, the B-2 Spirit, and other elite aircraft within the Air Force Arsenal.” Wings Over Wayne is a family-friendly expo including the Kids’ Zone, occupying one of the largest aircraft hangars on the base. A $10 admission charge covers access to the Zone for the entire day. “There is something for everyone,” said Colonel Yates. “Come out and witness this spectacular show while enjoying great food and fun with your family and ours.” “For the more serious air show enthusiasts, the two-day show has evolved into an air show week,” said Mayor Allen. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

1945-12-11 GO-116 728 ROB Central Europe Campaign Award

GO 116 SWAR DEPARTMENT No. 116. WASHINGTON 25, D. C.,11 December- 1945 UNITS ENTITLED TO BATTLE CREDITS' CENTRAL EUROPE.-I. Announcement is made of: units awarded battle par- ticipation credit under the provisions of paragraph 21b(2), AR 260-10, 25 October 1944, in the.Central Europe campaign. a. Combat zone.-The.areas occupied by troops assigned to the European Theater of" Operations, United States Army, which lie. beyond a line 10 miles west of the Rhine River between Switzerland and the Waal River until 28 March '1945 (inclusive), and thereafter beyond ..the east bank of the Rhine.. b. Time imitation.--22TMarch:,to11-May 1945. 2. When'entering individual credit on officers' !qualiflcation cards. (WD AGO Forms 66-1 and 66-2),or In-the service record of enlisted personnel. :(WD AGO 9 :Form 24),.: this g!neial Orders may be ited as: authority forsuch. entries for personnel who were present for duty ".asa member of orattached' to a unit listed&at, some time-during the'limiting dates of the Central Europe campaign. CENTRAL EUROPE ....irst Airborne Army, Headquarters aMd 1st Photographic Technical Unit. Headquarters Company. 1st Prisoner of War Interrogation Team. First Airborne Army, Military Po1ie,e 1st Quartermaster Battalion, Headquar- Platoon. ters and Headquarters Detachment. 1st Air Division, 'Headquarters an 1 1st Replacementand Training Squad- Headquarters Squadron. ron. 1st Air Service Squadron. 1st Signal Battalion. 1st Armored Group, Headquarters and1 1st Signal Center Team. Headquarters 3attery. 1st Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. 19t Auxiliary Surgical Group, Genera]1 1st Special Service Company. Surgical Team 10. 1st Tank DestroyerBrigade, Headquar- 1st Combat Bombardment Wing, Head- ters and Headquarters Battery.: quarters and Headquarters Squadron. -

PRESS RELEASE – Chuck Yeager

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE YEAGER AIRPORT MOURNS PASSING OF GENERAL CHUCK YEAGER Yeager Airport Staff and the Central West Virginia Regional Airport Board Members are mourning the loss of Brig. Gen. Charles “Chuck” Yeager today. His bravery and dedication will be remembered around the world for generations to come. “Gen. Yeager is a true pioneer in the world of aviation,” said Yeager Airport Director and CEO NicK Keller. “It is rare to be the first to ever do something, and Gen. Yeager did that by breaking the sound barrier and putting our great country ahead of its time in aviation.” General Yeager got his start as a pilot in 1941 when he signed for the Army Air Corps, now Known as the U.S. Air Force. Yeager’s military career spanned six decades and four wars. During World War II, Gen. Yeager flew 64 missions and shot down 13 German planes. Yeager’s plane was shot down over France in 1944 but he escaped capture. After the war, in true West Virginia fashion, Yeager continued serving his country as a flight instructor and test pilot at Wright Field in Ohio. It was there that his exceptional sKills were quicKly recognized, and he was chosen to be the first to fly the rocKet-powered Bell X-1. “General Yeager exemplified everything it means to be a West Virginian”, said Central West Virginia Regional Airport Authority Board Chairman Ed Hill. “Born and raised in Lincoln County, General Yeager’s hard work, dedication, skill, and bravery defined his historic career. Our entire Board is saddened by the loss of a fellow West Virginian, and a leader in aviation.” Yeager made history in 1947, when his Bell X-1 broke the speed of sound over a lake in Southern California. -

George Cooper

George Cooper NASA Ames Hall of Fame The popular conception of a test pilot is of a glamorous, romantic figure, composed of equal parts of right-stuff cool and devil-may-care bravado. In reality, though, test flying is a demanding and exacting task which requires not only the steel nerves and exceptional skill of the expert pilot, but also the analytical mind and insatiable curiosity of the dedicated engineer. In almost thirty years at Ames, George Cooper displayed all these qualities as he made invaluable contributions to aeronautical knowledge -- contributions whose impact continues long after his retirement from NASA. After serving as a fighter pilot with the Army Air Force in World War II, Cooper became a NACA test pilot at Ames in 1945. He did extensive research in transonic performance with various aircraft, exploring the tricky and treacherous qualities of near-Mach 1 handling characteristics (and incidentally breaking the sound barrier almost routinely, notwithstanding the more storied exploits of Muroc rocket jockeys such as Chuck Yeager and Scott Crossfield!). Cooper also performed detailed tests developing design criteria for one of the most dangerous tasks faced by any aviator: carrier approach and landings. Using the F-94 fighter, he developed methods of in-flight thrust reversal to better control the aircraft’s speed and flightpath, including its final approach, resulting in improved touchdown precision and safer landings. Although nearly every parameter of an aircraft's performance can be tested, described and ultimately predicted with mathematical precision, one essential factor has always been difficult to isolate: the interface between the individual aircraft and the human being flying it. -

Brigadier General Chuck Yeager Collection, 1923-1987

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2010 0455: Brigadier General Chuck Yeager Collection, 1923-1987 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons GENERAL CHARLES E. "CHUCK" YEAGER PAPERS Accession Number: 1987/0455 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2010 • GENERAL CHARLES E. "CHUCK" YEAGER PAPERS Accession Number: 455 Processed by: Kathleen Bledsoe, Nat DeBruin, Lisle Brown, Richard Pitaniello Date Finally Completed: September 2010 Location: Special Collections Department Chuck Yeager and Glennis Yeager donated the collection in 1987. Collection is closed to the public until the death of Charles and Glennis Yeager . • -2- TABLE OF CONTENTS Brigadier General Chuck E. "Chuck" Yeager ................................................................................ 4 The Inventory - Boxed Files ....................................................................................................... 9 The Inventory - Flat Files ......................................................................................................... 62 The Inventory - Display Cases in the General Chuck Yeager Room ....................................... 67 Accession 0234: Scrapbook and Clippings compiled by Susie Mae (Sizemore) Yeager..................75 -

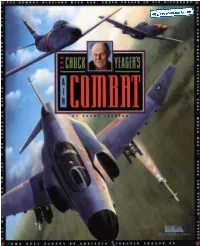

Chuck Yeagers Air Combat - Manual.Pdf

★ AIR COMBAT ★ 1 A DIFFERENT KIND OF COMBAT You’ve spent your life training to be a fighter pilot and dreaming of the day you’d actually get to fly. Hours, weeks, years invested in practice and training. All your hard work and time finally pay off and you develop into a world renown ace. You owe a lot to the flying aces that came before you. The teachers who taught you excellence. You pay them back by teaching other green boys about what it takes to be a flying ace and the edge they need for fighting well. You put back what you took out so more pilots can train and defend the nation. There are, however, some selfish aces out there who don’t give a damn about anyone else. These aces take all they can and say ‘to hell with the pros who came before’. Software publishing is much the same: most consumers pay for their software, but some green boys out there don’t. They copy software and don’t pay their dues to the teams responsible for bringing them the goods in the first place. When that happens, software companies don’t have the money they need to keep turning out the best software they can — some even go under. Electronic Arts is an ace in the field, giving you the best we can. Help us to keep putting out the best by stopping software piracy. As a member of the Software Publishers Association (SPA), Electronic Arts supports the fight against the illegal copying of personal computer software. -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

Famed Air Force Pilot Chuck Yeager Dies Associated Press Said in a Statement

e PARTLYEdition SUNNY 57 • 46 | TUESDAY, DECEMBER 8, 2020 | theworldlink.com Follow us online: facebook.com/theworldnewspaper twitter.com/TheWorldLink instagram.com/theworldlink Famed Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager dies Associated Press said in a statement. the hills of West Virginia, flew “Sure, I was apprehensive,” he apart,” Yeager said. “Gen. Yeager’s pioneering and for more than 60 years, including said in 1968. “When you’re fool- Sixty-five years later to the Retired Air Force Brig. Gen. innovative spirit advanced Amer- piloting an X-15 to near 1,000 ing around with something you minute, on Oct. 14, 2012, Yeager Charles “Chuck” Yeager, the ica’s abilities in the sky and set mph (1,609 kph) at Edwards in don’t know much about, there commemorated the feat, flying in World War II fighter pilot ace our nation’s dreams soaring into October 2002 at age 79. has to be apprehension. But you the back seat of an F-15 Eagle as and quintessential test pilot who the jet age and the space age. He “Living to a ripe old age is not don’t let that affect your job.” it broke the sound barrier at more showed he had the “right stuff” said, ‘You don’t concentrate on an end in itself. The trick is to The modest Yeager said in than 30,000 feet (9,144 meters) when in 1947 he became the first risks. You concentrate on results. enjoy the years remaining,” he 1947 he could have gone even above California’s Mojave person to fly faster than sound, No risk is too great to prevent said in “Yeager: An Autobiogra- faster had the plane carried more Desert. -

Public Edition

http://www.caffrenchwing.fr AIRSHOWCAF FRENCH WING - BULLETIN MENSUEL - MONTHLY NEWSLETTER http://www.lecharpeblanche.fr PUBLIC EDITION http://www.worldwarbirdnews.com Volume 19 - N°12 - December 2014 EDITORIAL Merry Christmas erial activites being A scarce these days, I hope you will enjoy this new issue of our newsletter prepared by our friend Bertrand. In it you will read a very interesting article by Roger Robert about the B-29/B-24 and Happy New Year ! Squadron with a presentation of Vic Agather, who was behind the acquisition of the bomber which has become the emblem of the CAF: the B-29 «Fifi» You will also discover with : CAF B-29/B-24 Squadron pleasure the first part of the photos taken by Greek Photo pilot “Pappy” Manthos, which Bertrand had presented in the previous issue of Airshow. I would like to end by wishing you all a Merry Christmas, with lots of aviation presents beneath the Christmas tree! - Stéphane Duchemin CAF B-29/B-24 SQUADRON : Atlee «Pappy» Manthos «Pappy» : Atlee Photo «PAPPY» MANTHOS’ PHoto ALBUMS Airshow - Public Edition Airshow is the monthly newsletter of the CAF French Wing. This "public" edition is meant for people who are not members of the association. Content which is for members only may have been removed from this edi- tion. To subscribe to the public edition of Airshow, go to our website and fill in the subscription form: Subscribe to the public edition of Airshow NB: Subscription to the public edition of Airshow is completely free and can be cancelled at any time.