Spatial and Temporal Considerations of Hydroelectric Energy Production in Northern Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

Report on Public Forum

Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights, Freedoms and Democracy Report and Recommendations for Policy Direction of a Public Forum organized by the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group Ottawa, February 17, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................2 ABOUT THE ICLMG .............................................................................................................2 BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................4 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY DIRECTION ..........................................................14 PROCEEDINGS......................................................................................................................16 CONCLUDING REMARKS...................................................................................................84 ANNEXES...............................................................................................................................87 ANNEXE I: Membership of the ICLMG ANNEXE II: Program of the Public Forum ANNEXE III: List of Participants/Panelists Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights Freedoms and Democracy 2 __________________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Forum session reporting -

2010-2011 Annual Report

First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority CONTACT INFORMATION Head Office Box 10460 Opaskwayak, Manitoba R0B 2J0 Telephone: (204) 623-4472 Facsimile: (204) 623-4517 Winnipeg Sub-Office 206-819 Sargent Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 0B9 Telephone: (204) 942-1842 Facsimile: (204) 942-1858 Toll Free: 1-866-512-1842 www.northernauthority.ca Thompson Sub-Office and Training Centre 76 Severn Crescent Thompson, Manitoba R8N 1M6 Telephone: (204) 778-3706 Facsimile: (204) 778-3845 7th Annual Report 2010 - 2011 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 16 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 FIRST NATION AGENCIES OF NORTHERN MANITOBA ABOUT THE NORTHERN AUTHORITY First Nation leaders negotiated with Canada and Manitoba to overcome delays in implementing the AWASIS AGENCY OF NORTHERN MANITO- Aboriginal Justice Inquiry recommendations for First Nation jurisdiction and control of child welfare. As a result, the First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority (Northern BA Authority) was established through the Child and Family Services Authorities Act, proclaimed in November 2003. Cross Lake, Barren Lands, Fox Lake, God’s Lake Narrows, God’s River, Northlands, Oxford House, Sayisi Dene, Shamattawa, Tataskweyak, War Lake & York Factory First Nations Six agencies provide services to 27 First Nation communities and people in the surrounding areas in Northern Manitoba. They are: Awasis Agency of Northern Manitoba, Cree Nation Child and Family Caring Agency, Island Lake First Nations Family Services, Kinosao Sipi Minosowin Agency, CREE NATION CHILD AND FAMILY CARING Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation FCWC and Opaskwayak Cree Nation Child and Family Services. -

Appendix 1 What We Heard from Policy Communities

Appendix 1 What we heard from policy communities Background In the Terms of Reference issued by the Minister of Conservation on September 1 2011, the Clean Environment Commission was asked to “hear evidence from Manitobans regarding the impacts of Lake Winnipeg regulation since the project was put into commercial use by Manitoba Hydro on August 1, 1976.” Over the period of approximately one month (January 12, 2015 to February 18, 2015), the Clean Environment Commission (CEC) attended 17 communities surrounding Lake Winnipeg.1 They also held two evening public sessions in Winnipeg and received a number of written submissions from the public.2 The CEC heard from many residents and users around the Lake including: cottage owners, permanent residents, Indigenous people, agricultural farmers, commercial and subsistence fishermen, and people and organizations from the tourism and recreation industry. There is disagreement in terms of the implications of Lake Winnipeg Regulation on Lake Winnipeg. Manitoba Hydro argues that its effects are generally either positive, benign or insignificant. Others take the position that LWR in conjunction with other Hydro activities has adverse and ongoing effect on the Lake. Among the prominent concerns are: • Lack of confidence in Manitoba Hydro, the Province and the CEC Hearing process on LWR • Lack of transparency of Manitoba Hydro and Manitoba Government operations of LWR • Lack of meaningful ongoing engagement • Sense of exclusion by upstream, downstream and Indigenous people • A sense that Manitoba hydro -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Accession No. 1986/428

-1- Liberal Party of Canada MG 28 IV 3 Finding Aid No. 655 ACCESSION NO. 1986/428 Box No. File Description Dates Research Bureau 1567 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. I July 1981 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Saskatchewan, Vol. I and Sept. 1981 II Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Alberta, Vol. II May 20, 1981 1568 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Manitoba, Vols. II and III 1981 Liberal caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. IV 1981 Elections & Executive Minutes 1569 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings Apr. 29, 1979 to Apr. 13, 1980 Poll by poll results of October 1978 By-Elections Candidates' Lists, General Elections May 22, 1979 and Feb. 18, 1980 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings June-Dec. 1981 1984 General Election: Positions on issues plus questions and answers (statements by John N. Turner, Leader). 1570 Women's Issues - 1979 General Election 1979 Nova Scotia Constituency Manual Mar. 1984 Analysis of Election Contribution - PEI & Quebec 1980 Liberal Government Anti-Inflation Controls and Post-Controls Anti-Inflation Program 2 LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA MG 28, IV 3 Box No. File Description Dates Correspondence from Senator Al Graham, President of LPC to key Liberals 1978 - May 1979 LPC National Office Meetings Jan. 1976 to April 1977 1571 Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John's West (Nfld) Riding Profiles St. John's East (Nfld) Riding Profiles Burin St. George's (Nfld) Riding Profiles Humber Port-au-Port-St. -

Collection: Green, Max: Files Box: 42

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Green, Max: Files Folder Title: Briefing International Council of the World Conference on Soviet Jewry 05/12/1988 Box: 42 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name GREEN, MAX: FILES Withdrawer MID 11/23/2001 File Folder BRIEFING INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL & THE WORLD FOIA CONFERENCE ON SOVIET JEWRY 5/12/88 F03-0020/06 Box Number THOMAS 127 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages 1 NOTES RE PARTICIPANTS 1 ND B6 2 FORM REQUEST FOR APPOINTMENTS 1 5/11/1988 B6 Freedom of Information Act - [5 U.S.C. 552(b)] B-1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA) B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA) B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA) B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted Invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA) B-7 Release would disclose Information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA) B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA) B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA) C. -

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a Foundation in Northern Manitoba

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba Karla Zubrycki Dimple Roy Hisham Osman Kimberly Lewtas Geoffrey Gunn Richard Grosshans © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org November 2016 Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is one Head Office of the world’s leading centres of research and innovation. The Institute provides practical solutions to the growing challenges and opportunities of 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 integrating environmental and social priorities with economic development. Winnipeg, Manitoba We report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained Canada R3B 0T4 through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, stronger global networks, and better engagement among researchers, citizens, Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 businesses and policy-makers. Website: www.iisd.org Twitter: @IISD_news IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province -

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: the Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: The Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976 by Joel Kropf, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 31,2007 © 2007 Joel Kropf Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

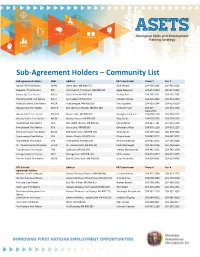

Sub-‐Agreement Holders – Community List

Sub-Agreement Holders – Community List Sub-Agreement Holders Abbr. Address E&T Coordinator Phone # Fax # Garden Hill First Nation GHFN Island Lake, MB R0B 0T0 Elsie Monias 204-456-2085 204-456-9315 Keewatin Tribal Council KTC 23 Nickel Rd, Thompson, MB R8N 0Y4 Aggie Weenusk 204-677-0399 204-677-0257 Manto Sipi Cree Nation MSCN God's River, MB R0B 0N0 Bradley Ross 204-366-2011 204-366-2282 Marcel Colomb First Nation MCFN Lynn Lake, MB R0B 0W0 Noreena Dumas 204-356-2439 204-356-2330 Mathias Colomb Cree Nation MCCN Pukatawagon, MB R0B 1G0 Flora Bighetty 204-533-2244 204-553-2029 Misipawistik Cree Nation MCN'G Box 500 Grand Rapids, MB R0C 1E0 Melina Ferland 204-639- 204-639-2503 2491/2535 Mosakahiken Cree Nation MCN'M Moose Lake, MB R0B 0Y0 Georgina Sanderson 204-678-2169 204-678-2210 Norway House Cree Nation NHCN Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Tony Scribe 204-359-6296 204-359-6262 Opaskwayak Cree Nation OCN Box 10880 The Pas, MB R0B 2J0 Joshua Brown 204-627-7181 204-623-5316 Pimicikamak Cree Nation PCN Cross Lake, MB R0B 0J0 Christopher Ross 204-676-2218 204-676-2117 Red Sucker Lake First Nation RSLFN Red Sucker Lake, MB R0B 1H0 Hilda Harper 204-469-5042 204-469-5966 Sapotaweyak Cree Nation SCN Pelican Rapids, MB R0B 1L0 Clayton Audy 204-587-2012 204-587-2072 Shamattawa First Nation SFN Shamattawa, MB R0B 1K0 Jemima Anderson 204-565-2041 204-565-2606 St. Theresa Point First Nation STPFN St. Theresa Point, MB R0B 1J0 Curtis McDougall 204-462-2106 204-462-2646 Tataskweyak Cree Nation TCN Split Lake, MB R0B 1P0 Yvonne Wastasecoot 204-342-2951 204-342-2664 -

970 Canada Year Book 1980-81 the Senate

970 Canada Year Book 1980-81 The Hon. Charles Ronald McKay Granger, The Hon. Monique Begin, September 15,1976 September 25, 1967 TheHon. Jean-Jacques Blais, September 15, 1976 The Hon. Bryce Stuart Mackasey, February 9, 1968 The Hon. Francis Fox, September 15, 1976 The Hon. Donald Stovel Macdonald, April 20, The Hon. Anthony Chisholm Abbott, September 1968 15,1976 The Hon. John Can- Munro, April 20, 1968 TheHon. lonaCampagnolo, September 15, 1976 The Hon. Gerard Pelletier, April 20, 1968 The Hon. Joseph-Philippe Guay, November 3, The Hon. Jack Davis, April 26, 1968 1976 The Hon. Horace Andrew (Bud) Olson, July 6, The Hon. John Henry Horner, April 21,1977 1968 The Hon. Norman A, Cafik, September 16, 1977 The Hon. Jean-Eudes Dube, July 6, 1968 The Hon, J. Gilles Lamontagne, January 19, 1978 The Hon. Stanley Ronald Basford, July 6, 1968 The Hon. John M. Reid, November 24, 1978 The Hon. Donald Campbell Jamieson, July 6, 1968 The Hon. Pierre De Bane, November 24, 1978 The Hon. Eric William Kierans, July 6, 1968 The Rt. Hon. Jutes Leger, June 1, 1979 The Rt. Hon. Joe Clark, June 4, 1979 The Hon. Robert Knight Andras, July 6, 1968 The Hon. Walter David Baker, June 4, 1979 The Hon. James Armstrong Richardson, July 6, The Hon. Flora MacDonald, June 4, 1979 1968 The Hon James A. McGrath, June 4, 1979 The Hon. Otto Emil Lang, July 6, 1968 The Hon, Erik H. Nielsen, June 4, 1979 The Hon. Herbert Eser Gray, October 20, 1969 The Hon. Allan Frederick Lawrence, June 4, 1979 The Hon. -

Hansard 33 1..146

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 137 Ï NUMBER 105 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, October 30, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 6695 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, October 30, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. kidney in its title rather than having a relatively obscure academic title. Prayers The petitioners call upon parliament to encourage the Canadian institutes of health research to explicitly include kidney research as one of the institutes in its system to be named the institute of kidney ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS and urinary tract diseases. Ï (1005) *** [English] [Translation] YUKON NORTHERN AFFAIRS PROGRAM DEVOLUTION QUESTIONS ON THE ORDER PAPER TRANSFER AGREEMENT Mr. Geoff Regan (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of Hon. Robert Nault (Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern the Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I Development, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I have the honour to table, in both would ask that all questions be allowed to stand. official languages, the Yukon Northern Affairs Program Devolution Transfer Agreement. The Deputy Speaker: Is that agreed? *** Some hon. members: Agreed. GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS Mr. Geoff Regan (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, GOVERNMENT ORDERS pursuant to Standing Order 36(8) I have the honour to table, in both official languages, the government's response to two petitions. Ï (1010) *** [English] COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE CONSTITUTION OF CANADA PROCEDURE AND HOUSE AFFAIRS Hon.