Oral History Interview with Marguerite Van Cook, 2016 September 19-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Ouch Podcast

Ouch Talk Show 21 December 2016 bbc.co.uk/ouch Presented by Damon Rose, Beth Rose and Emma Tracey Punk Therapy EMMA Before we get into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch I just want to tell you about an event Ouch will be holding in early 2017. It’s a live storytelling night and the theme is love and relationships. So, if you have a suitable story that you fancy telling in front of a live audience email it to [email protected]. Maybe you’re blind and your partner snogged someone right in front of you at a party. Or maybe your differences make intimacy a little tricky. All we ask is that you are disabled, that the story is true and that it’s about disability in some way. Bookmark bbc.co.uk/ouch/disability for further details. Now, let’s get back into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch. [Music playing – Christmas as a Punk] What do you when you’ve turned 18 or finished formal education if you’ve got learning disabilities? Electric Umbrella sought a solution and wound up with an amazing Christmas single, and they’re here on a quest to make Christmas As A Punk number one. This is Inside Ouch; I’m Emma Tracey in Edinburgh. In London we have Damon Rose. DAMON Hello. EMMA We have Beth Rose. BETH Hi there. EMMA And we have three members of Electric Umbrella. Hello. BAND Hello! EMMA Awesome. So, we’ve got Tom Billington. TOM Hello. EMMA Used to be in Mohair touring with Razorlight and the The Killers. -

1912 Durfee Record

The Durfee Record Senior Class PUBLISHED B Y B . M . C. Durfee Hígh School 1912 To Principal George F. Pope : This book isrespectfully dedicated , as a mark obymembersfteem thees of the class of 1912. Principal George F . Pope e Faculty GEORGE FREDERICK POPE, A . M . Principal . Mathematics. WILLARD HENRY POOLE, A . B . Vice-Principal Physics and Chemistry . HANNAH REBECCA ADAMS, English . DAVID EMERSON GREENAWAY, A . B . History and Civil Government EMILY ELLEN WINWARD , French . WILLIAM JOHN WOODS, S. B ., Mechanics DAVID YOUNG COMSTOCK, A . M ., Latin . and Drawing . SAMUEL N . F. SANFORD, Secretary an d Librarian . JAMES WALLIS, Commercial Department . CHARLES FREDERIC WELLINGTON , A . B . GERTRUDE MARY BAKER, English . Assistant Secretary . HARRIET ANTHONY MASON SMITH, French . HELEN HATHEWAY IRONS, B . L ., French . ASA ELDRIDGE GODDARD, A . M ., Mathe- LENA PEASE ABBE, A. B ., Algebra . matics, Astronomy and Geology . FLORENCE ESTHER LOCKE, A. B ., German . HARRIET TRACY MARVELL, A. B . , Physiography, Physiology, Reviews . HARRIET DAVIS PROCTOR, A. B ., German and English . HERBERT MIL LER CHACE SKINNER, S. B . Mechanics and Drawing . ANSEL SYLVESTER RICHARDS, A . M . , English . EUNICE ALMENA LYMAN, A . B ., History . SUSAN WILLIAMS STEVENS, German an d CHARLES ADAMS PERRY, Mechanics an d Mathematics . Drawing. ROBERT REMINGTON GOFF, A . B ., Mathe- CECIL THAYER DERRY, A . B ., A . M . matics . Greek and Latin . JOHN SMITH BURLEY, PH . B ., English. BLANCHE AVELINE VERDER, B . S ., English WILLIAM WILSON GARDNER, A . B., English and History. and Mathematics . ALICE GERTRUDE LANGFORD, A. B ., Lati n LINDA RICHARDSON, A . M ., History and and History. Latin . WILLIAM DUNNIGAN MORRISON, A. B., ALICE BOND DAMON, A. -

Dennis Chambers

IMPROVE YOUR ACCURACY AND INDEPENDENCE! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE FUSION LEGEND DENNIS CHAMBERS SHAKIRA’S BRENDAN BUCKLEY WIN A $4,900 PEARL MIMIC BLONDIE’S PRO E-KIT! CLEM BURKE + DW ALMOND SNARE & MARCH 2019 GRETSCH MICRO KIT REVIEWED NIGHT VERSES’ ARIC IMPROTA FISHBONE’S PHILIP “FISH” FISHER THE ORIGINAL. ONLY BETTER. The 5000AH4 combines an old school chain-and-sprocket drive system and vintage-style footboard with modern functionality. Sought-after DW feel, reliability and playability. The original just got better. www.dwdrums.com PEDALS AND ©2019 Drum Workshop, Inc. All Rights Reserved. HARDWARE 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 LAYER » EXPAND » ENHANCE HYBRID DRUMMING ARTISTS BILLY COBHAM BRENDAN BUCKLEY THOMAS LANG VINNIE COLAIUTA TONY ROYSTER, JR. JIM KELTNER (INDEPENDENT) (SHAKIRA, TEGAN & SARA) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (STUDIO LEGEND) CHARLIE BENANTE KEVIN HASKINS MIKE PHILLIPS SAM PRICE RICH REDMOND KAZ RODRIGUEZ (ANTHRAX) (POPTONE, BAUHAUS) (JANELLE MONÁE) (LOVELYTHEBAND) (JASON ALDEAN) (JOSH GROBAN) DIRK VERBEUREN BEN BARTER MATT JOHNSON ASHTON IRWIN CHAD WACKERMAN JIM RILEY (MEGADETH) (LORDE) (ST. VINCENT) (5 SECONDS OF SUMMER) (FRANK ZAPPA, JAMES TAYLOR) (RASCAL FLATTS) PICTURED HYBRID PRODUCTS (L TO R): SPD-30 OCTAPAD, TM-6 PRO TRIGGER MODULE, SPD::ONE KICK, SPD::ONE ELECTRO, BT-1 BAR TRIGGER PAD, RT-30HR DUAL TRIGGER, RT-30H SINGLE TRIGGER (X3), RT-30K KICK TRIGGER, KT-10 KICK PEDAL TRIGGER, PDX-8 TRIGGER PAD (X2), SPD-SX-SE SAMPLING PAD Visit Roland.com for more info about Hybrid Drumming. Less is More Built for the gigging drummer, the sturdy aluminum construction is up to 34% lighter than conventional hardware packs. -

Reinblättern (Pdf)

Philipp Meinert Von den Sechzigern bis in die Gegenwart Philipp Meinert, 1983 ausgerechnet in Gladbeck geboren, erlebte im Ruhrgebiet eine solide Punksozialisation. Inhalt Studium der Sozialwissenschaften in Bochum. Seit 2010 neben seiner Lohnarbeit regelmäßiger Schreiber und Interviewer für verschiedene Online- und Print- medien, hauptsächlich für das »Plastic Bomb Fanzine«. Über dieses Buch und Einleitung ...................................... 9 2013 gemeinsam mit Martin Seeliger Herausgeber des Sammelbandes »Punk in Deutschland. Sozial- und kultur- »A walk on the wild side« 15 wissenschaftliche Per spektiven«. Lebt in Berlin. Die ziemlich queere Welt des Prä-Punks in New York ................... Lou Reed: Der bisexuelle Pate des Punk .................................. 17 Glam: Glitzernde Vorzeichen des Punk .................................. 25 »Personality Crisis« Die New York Dolls als Bindeglied 30 zwischen Punk und Glam ............................................. »Hey little Girl! I wanna be your boyfriend.« Mit den Ramones 35 wird es heterosexueller................................................ »Immer der coolste Typ im Raum« - Interview Danny Fields ............... 38 »Man Enough To Be a Woman« – Jayne County, die transsexuelle 44 Punkgeburtshelferin ................................................... Punk-Genese in England .............................................. 57 Die englische Punkrevolution als kreative Befreiung von Frauen ............. 67 Interview mit Bertie Marshall ......................................... -

Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9Pm

For Immediate Release contact [email protected], 646-492-4076 Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9pm I think that my art serves as a way of putting out the fuse before it becomes a ballistic bomb of some sort. Some people are at odds with the world and they become serial killers, and others become artists. –Jayne County From February 4 – March 11, 2018, PARTICIPANT INC is honored to present Jayne County, Paranoia Paradise, the first retrospective exhibition of County’s visual artwork, curated by Michael Fox. Although County’s artistic output began in experimental theater in the late 1960s-early ‘70s, including work with Theater of the Ridiculous and in Andy Warhol’s Pork, she is perhaps most well-known as a rock singer and performer. This exhibition takes its title from one of County’s songs, Paranoia Paradise, which she famously performed as the character of “Lounge Lizard” in Derek Jarman’s 1978 film, Jubilee. Selections of her earliest known paintings and works on paper made in the early ‘80s while living in Berlin will be exhibited alongside works made up until the present, with approximately eighty pieces on view from County’s studio as well as several private collections. A presentation of related ephemeral materials from County’s archive, as well as photographs by Bob Gruen, Leee Black Childers, and Michael Fox will accompany the exhibition and further illuminate her legendary contributions to music, film, performance, as well her role as forebear and gender pioneer as the first openly transgender rock performer. -

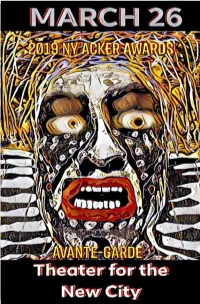

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

“Heretic Streak”: the Orwellian Aesthetic in Ray Davies' Song Writing And

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE AGH Tom 15/2 • 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2016.15.2.7 Izabela Curyłło-Klag* Jagiellonian University in Krakow UTOPIA, DYSTOPIA AND THE “HERETIC STREAK”: THE ORWELLIAN AESTHETIC IN RAY DAVIES’ SONG WRITING AND OTHER CREATIVE PROJECTS The article explores the infl uence of Orwell’s fi ction on the creative output of Ray Davies, one of Britain’s fi nest songwriters and the erstwhile frontman of The Kinks, a ‘British Invasion’ group. The Davies oeuvre can be placed alongside Orwell’s work due to its entertainment value, sharpness of ob- servation and complex, confl icted socio-political sympathies. By balancing utopian visions with dystopian premonitions and by offering regular critiques of the culture they hold dear, Orwell and Davies represent the same tradition of cautious patriotism. They also share a similar aesthetic, communicating their insights through humour, self-mockery and acerbic wit. Keywords: Orwell, Ray Davies, pop culture, dystopia, utopia In the opening frame of a documentary on The Kinks, Hugh Fielder, a well-known English music critic, comments: “If George Orwell wrote songs, and was not a member of the socialist party, he’d be writing Ray Davies’ songs”. He then immediately checks himself: “Sorry, that’s a literary allusion, it’s probably gonna go whoosh” (The Kinks Story 2010: 3’21). Mentioning literature with reference to a British Invasion band is not exactly the done thing: rockers do not usually enthuse over writers, even if they share their love of words. Not long ago for instance, the frontman of Oasis declared that reading fi ction is a waste of time, and dismissed the whole publishing business as elitist, since it allows “people who write and read and review books [to put] themselves a tiny little bit above the rest of us” (Gallagher 2013). -

Download PDF Booklet

www.zerecords.com CAN YOU IMAGINE ALL THAT MILK? The year was 1980, and Detroit was getting ready to play host to thousands of Re- publican conventioneers who were holding their quadrennial shindig in the Motor City. In a breathtaking moment of silliness, someone decided to install brand-new awnings CAN WE WHO on the windows of the recently abandoned Statler Hotel, so as not to offend any of the visiting GOP functionaries with the depressing urban financial realities of the day. Meanwhile, the members of Detroit band Was (Not Was) were engaging in a bold mu- sical experiment, splicing the genes of jazz, rock, R&B, and funk. With their futuristic grooves and intelligent (if twisted) lyrics, Was (Not Was) didn’t hide the local decay MAN TH E SHIP behind fake awnings. It gathered its ethnically diverse ranks, dressed the decay up in some fine threads and took it out dancing. The band’s ringleaders were Don Was (Donald Fagenson) and David Was (David Weiss). These brothers (of the soul variety) were in a good position to point out the absurdities of American life in the early ‘80s. Hailing from the scrubbed inner-ring De- OF STATE DENY troit suburb of Oak Park, the pair met in eighth grade, appropriately enough when they were both waiting in the principal’s office for discipline. The young friends cut their teeth listening to the homegrown sounds of Motown singles and the MC5. Add plenty of LSD and a healthy dose of the Firesign Theater to their natural mischievousness, mix well, and you’ve got a good idea of the part of the woodwork these freaks creaked IT IS SOME WHAT out of. -

A Guide to Local Shops

A GUIDE TO EAST VILLAGE LOCAL SHOPS EIGHTH EDITION CAFÉS, ETC. 1 – 56 SHOP LOCAL! BAKERY / CAFE / CANDY & CHOCOLATE / EGG CREAM / ICE CREAM / JUICE BAR / TEA SHOP When you spend your money locally, you... • ENSURE economic diversity and stability • KEEP more of your money in your community FASHION 57 – 163 • CREATE local jobs with fair living wages ACCESSORIES / BRIDAL & FORMAL / CHILDREN’S / CLOTHING • SUSTAIN small business owners / HATS / HOME ACCESSORIES & FURNITURE / JEWELRY / • STRENGTHEN the local economy LEATHER WORK / SHOES / VINTAGE, THRIFT, CONSIGNMENT • DEFEND our neighborhood’s identity and creativity GALLERIES 164 – 175 Get Local! is an initiative of the East Village Community Coalition to help build long-lasting communities that keep our neighborhood unique, independent, and sustainable. GIFTS, ETC. 176 – 193 FLORIST / GIFTS / POTTERY / RELIGIOUS GOODS / TOYS ABOUT EVCC We work to recognize, sustain, and support the architectural HEALTH & BEAUTY 194 – 310 and cultural character of the East Village. BARBER SHOP / CUSTOM PERFUME / DENTAL & MEDICAL EVCC MEMBERS CARE / HAIR SALON / HAIR SUPPLY / OPTICIANS & EYEWEAR / •Advocate for the preservation of local historic resources PHARMACY / SPA / TATTOOS & BODY PIERCING / and significant architecture YOGA, PILATES & FITNESS •Promote Formula Retail regulations to protect small busi- nesses and maintain our diversified, livable neighborhood CULTURE, MUSIC, •Publish the Get Local! Guide to encourage shoppers to & ENTERTAINMENT 311 – 357 support diverse, locally-owned retail AUDIO EQUIPMENT / BOOKS / COMIC BOOKS / CONCERT JOIN US! If you feel as passionately as we do about & EVENT PROMOTION / CULTURAL & ARTS VENUES / FILM / local community in the East Village, join the cause: INSTRUMENTS / NEWSPAPERS & MAGAZINES / POETRY CLUB / RECORDS / VIDEO GAMES / VIDEO RENTAL Become a member Visit evccnyc.org to join. -

John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and Much, Much More

The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine of Art, Literature and Music! Number 9 $5.95 John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and much, much more . SENSITIVE SKIN MAGAZINE is also available online at www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com. Publisher/Managing Editor: Bernard Meisler Associate Editors: Rob Hardin, Mike DeCapite & B. Kold Music Editor: Steve Horowitz Contributing Editors: Ron Kolm & Tim Beckett This issue is dedicated to Chris Bava. Front cover: Prime Directive, by J.D. King Back cover: James Romberger You can find us at: Facebook—www.facebook.com/sensitiveskin Twitter—www.twitter.com/sensitivemag YouTube—www.youtube.com/sensitiveskintv We also publish in various electronic formats (Kindle, iOS, etc.), and have our own line of books. For more info about SENSITIVE SKIN in other formats, SENSITIVE SKIN BOOKS, and books, films and music by our contributors, please go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/store. To purchase back issues in print format, go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/back-issues. You can contact us at [email protected]. Submissions: www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/submissions. All work copyright the authors 2012. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner. All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. ISBN-10: 0-9839271-6-2 Contents The Forgetting