Klaveren, Tijdens, Hughie-Williams, Ramos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Brief Series

The Migration, Environment Migration, Environment and Climate Change: and Climate Change: Policy Brief Series is produced as part of the Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP) project funded by the European Union, implemented Policy Brief Series by IOM through a consortium with ISSN 2410-4930 Issue 4 | Vol. 2 | April 2016 six research partners. 2012 East Azerbaijan earthquakes © Mardetanha, 2012 Environmental migration and displacement in Azerbaijan: Highlighting the need for research and policies Irene Leonardelli, IOM Introduction From a geological and environmental point of view, the 362). Simultaneously, due to climate change, the country Caucasus region ‒ where the Republic of Azerbaijan is increasingly exposed to slow-onset processes, such (hereafter “Azerbaijan”) is located ‒ is a very active as water scarcity, salinization and pollution, rising and hazardous area; this is mainly reflected in the temperatures, sea-level fluctuation, droughts and soil intensity and the frequency of floods, storms, landslides, degradation. While natural disasters have displaced mudflows and earthquakes (ogli Mammadov, 2012:361, 67,865 people between 2009 and 2014 (IDMC, 2014), the YEARS This project is funded by the This project is implemented by the European Union International Organization for Migration 44_16 Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Policy Brief Series Issue 4 | Vol. 2 | April 2016 2 progressive exacerbation of environmental degradation Extreme weather events and slow-onset is thought to have significant adverse impacts on livelihoods and communities especially in certain areas processes in Azerbaijan of the country. Azerbaijan’s exposure to severe weather events and After gaining independence in 1991 as a result of the negative impacts on the population are increasing. -

Azerbaijan Azerbaijan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN National Report on the State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Azerbaijan Baku – December 2006 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 1. -

World Bank Document

75967 Review of World Bank engagement in the Public Disclosure Authorized Irrigation and Drainage Sector in Azerbaijan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized February 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized © 2012 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000I Internet: www.worldbank.org This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

SUD-CAUCASE.Ai

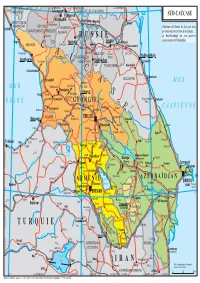

vers RÉP. DES v. PSEBAÏ vers TCHERKESSK vers GUEORGUIEVSK vers ASTRAKHAN 48° TOUAPSÉ ADYGUÉS Essentouki TERRITOIRE DE STAVROPOL ï 44° Piatigorsk Kra novka SUD-CAUCASE Kislovodsk Prokhladnyï Te TERRITOIRE DE Mozdok re Karatchaïevsk Baksan Kizliar k KRASNODAR RÉP. DES L'Abkhazie et l'Ossétie du Sud sont deux Sotchi KABARDINO- Terek KARATCHAÏS-TCHERKESSES BALKARIE provinces sécessionnistes de la Géorgie. Teberda R U S S I E Le Haut-Karabagh est une province Gagra Elbrous Grozny sécessionniste de l'Azerbaïdjan. 5642 T Naltchik Nazran Goudermes ABKHAZIE C yrnyaouz Khassaviourt Kardjine Argoun Goudaouta A Beslan - Kiziliourt 5204 INGOUCHIE Ourous Mestia OSSÉTIE DU Martan Makhatchkala uri Soukhoumi T go U Alaguir Vladikavkaz Kaspiïsk kvartcheli n NORD I TCHÉTCHÉNIE Bouïnaksk Otchamtchire C Kazbek Atchissou Oni 5037 Izberbach Zougdidi A 4492 DAGUESTAN Ossétie M E R M E R Tskhaltoubo Satchkhere du Sud Koutaïssi Tskhinvali Poti Senaki Tchiatoura S Zestafoni Samtredia Tianeti Daguestanskiïe Derbent N O I R E G É O R G I E Bejta Ogni Kaspi 4127 Ozourgueti Khachouri Telavi Kvareli E C A S P I E N N E Kobouleti Borjomi Gori Mtskheta ADJARIE B TBILISSI Gourodjaani Batoumi akouriani Zaqatala r mou Akhaltsikhe Roustavi Tchnori Sa Xaçmaz Hopa Bolnissi Akhalkalaki Qax Marneouli Dedoplis-Tskaro Quba e K I e o e Ardesen ou ri 4466 Kura ra S ki D v ci Trabzon Rize Pazar Artvin Ardahan (K Bazardüzü Alaverdi ü ee Çayeli Tachir Qazax r) Siy z n Tovuz Réservoir de Sürmene 3932 Lac de Ming e çevir Çildir Spitak Idjevan Minguetchaouri e Vanadzor e Gandja (Ming çevir) -

Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Transport Road Transport Services Department

Supplementary Appendix C Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Transport Road Transport Services Department EAST–WEST HIGHWAY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT RESETTLEMENT PLAN June 2005 THIS IS NOT AN ADB BOARD APPROVED DOCUMENT To: Head of the Road Maintenance Agency of Gornboy/Yevlax/Ganja/Xanlar The draft Resettlement Plan for the Rehabilitation of the East-West Corridor Road of the Azerbaijan Republic has been prepared by the Road Transport Service Department in accordance with the Azerbaijan law and ADB guidelines on resettlement. The Resettlement Plan covers land acquisition and other resettlement aspects for the rehabilitation of the road segments from Yevlax to Ganja and from Gazax to the border with Georgia. The draft Resettlement Plan is based on the studies of social and economic conditions of businesses, ordinary people and families that have been affected by the above mentioned road rehabilitation project as well as on the consultations with local authorities. The impact shown in the Resettlement Plan reflects the results of the Technical Assistance provided by the ADB. The draft Resettlement Plan will be upgraded and completely finalized in 2006 . This draft Resettlement Plan has been approved by RTSD and ADB and may be disclosed to all affected communities and people. We authorize your agency to disclose the Resettlement Plan to all concerned parties as necessary. Attachment: draft resettlement Plan – 54 pages Head of the Road Maintenance Division V. Hajiyev CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Outline of the Project 1.2 Status of the Road Reserve 2. SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN THE PROJECT AREA 2.1 Project Impact Areas 2.2 Social Profile of the Project Areas 3. -

Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

FT SPECIAL REPORT Azerbaijan Thursday March 12 2015 www.ft.com/reports | @ftreports Roman times. It did not stop Azerbaijan from hosting the 2012 Eurovision Song Inside Contest, and in June it hosts the inaugu- ral European Games, the biggest inter- Reform offers nationalsportseventeverstagedthere. Nagorno-Karabakh The games will take place against a conflict backdrop of troubling geopolitical and Important oil and gas economic developments for the young pipelines run close to state. The Ukrainian uprising that top- the front line the best hope pled President Viktor Yanukovich in February 2014 disturbed President Page 2 Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan. Not only was it a popular revolution against an authoritarian ruler, but the US and its Economy under for national western allies, regarded as partners in pressure Baku,openlysympathisedwiththepro- Devaluation and job democracyforcesonthestreetsofKiev. losses as oil price In what looked like an effort to forestall similar events at home, the slide hits hard stability Azerbaijani authorities began to crack Page 3 Foreign policy focuses on independence A long stretch of low Delicate balancing act Oil has given this former Soviet state great wealth oil prices would test the amid regional and but it still struggles on many fronts, says Tony Barber country’s economic model global powers Page 3 aterfront skyscrapers an experience it has no desire to repeat. downonpoliticaldissentandindepend- and blustery winds Azerbaijanstandsatacrossroadsofcivi- ent media even more than in the first Baku seeks a fresh role from the Caspian Sea lisations and markets, old and new, and decade under Mr Aliyev, who replaced in energy markets make Baku, Azerbai- derives its identity from multiple HeydarAliyev,hisfather,aspresidentin Plans are in train to W jan’s capital, look and sources. -

Ecosystems Assessment Report Azerbaijan.Pdf

Identification and implementation of adaptation response to Climate Change impact for Conservation and Sustainable use of agro-biodiversity in arid and semi-arid ecosystems of South Caucasus Ecosystem Assessment Report Baku, 2012 List of abbreviations ANAS Azerbaijan National Academy of Science EU European Union ECHAM 4 European Center HAMburg 4 IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change GIZ German International Cooperation GIS Geographical Information System GDP Gross Domestic Product GFDL Global Fluid Dynamics Model MENR Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources PRECIS Providing Regional Climate for Impact Studies REC Regional Environmental Center UN United Nations UNFCCC UN Framework Convention on Climate Change WB World Bank Table of contents List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. 6 I. Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 7 II. General ecological and socio-economic description of selected regions ....................................................... 8 2.1. Agsu district .............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1. General -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR5276 Implementation Status & Results Azerbaijan Second National Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P109961) Operation Name: Second National Water Supply and Sanitation Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 05-Jul-2011 (P109961) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Azerbaijan Approval FY: 2008 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): State Amelioration and Water Management Agency of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (SAWMA), State Amelioration and Water Management Company Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 27-May-2008 Original Closing Date 28-Feb-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 05-Jul-2011 Effectiveness Date 13-Jul-2009 Revised Closing Date 28-Feb-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To improve the availability, quality, reliability and sustainability of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services in selected regional (rayon) centers in Azerbaijan. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Component A: Rayon Investments 392.00 Component B: Institutional Modernization 15.80 Component C: Project Implementation and Management 1.60 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview This information is based on recent implementation support mission led by Manuel Marino and composed of Hadji Huseynov, Deepal Fernando, Gulana Hajiyeva and Norpulat Daniyarov and carried out through October 31- November 4, 2011. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Former President Kocharyan Arrested for Using Deadly Force in 2008 Russian, Armenian KOCHARYAN, from Page 1 Serious Concern About It

AUG 4, 2018 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXIX, NO. 3, Issue 4547 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Armenian Companies Former President Kocharyan Arrested To Take Part in Japan Tourism Expo For Using Deadly Force in 2008 YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Seven Armenian tourism companies will participate in Tourism YEREVAN (RFE/RL and Armenpress) — politically motivated. of a disputed presidential election held in Expo Japan 2018, from September 20 to 23, in Lawyers for former President Robert One of them, Aram Orbelian, said that February 2008, two months before he com- Tokyo, the Small and Medium Entrepreneurship Kocharyan said on Monday, July 30, that they expect Armenia’s Court of Appeals to pleted his second and final term. The accusa- Development National Center (SME DNC) founda- they will appeal a Yerevan district court’s start considering their petition this week. tion stems from the use of deadly force on tion announced. decision to allow law-enforcement authori- Kocharyan was arrested late on Friday, July On July 27, SME DNC executive director Arshak ties to arrest the former Armenian presi- 27, one day after being charged with “over- Grigoryan, president of the Tourism Committee, dent on coup charges which he denies as throwing the constitutional order” in the wake Hripsime Grigoryan, and executive director of the Tourism Development Foundation of Armenia Ara Khzmalyan signed a memorandum of cooperation for properly preparing and successfully participat- ing in the expo. According to the document, the sides will exchange their experience, knowledge and infor- mation with each other. -

Economic Research Centre Strengthening Municipalities In

Economic Research Centre Strengthening Municipalities in Azerbaijan Concept Paper This paper has been prepared within the framework of Oxfam, GB and ICCO, Netherlands co-funded project “The Role of Local self-governments in Poverty reduction in Azerbaijan” Expert group members working on the concept: Research Team Leader: Rovshan Agayev: Other Team Members: Gubad Ibadoglu Azer Mehtiyev Aydin Aslanov Translated by: Elshad Mikayilov Baku 2007 1 INTRODUCTION Democratic political system, creation of effective public management and eradication of socio-economic recession are the major challenges facing most of the world countries. The analysis of experience across highly developed countries reveals that the road to democratic and economic prosperity is quite clear. The matter has more to deal with the rejection of authoritarian type of management both in political and economic realms, establishment of market oriented relations and liberal economic environment. Liberal political and economic system in the country first and foremost presupposes deeper decentralization along with the autonomous strong municipal institutions from the perspectives of administration and financial capacity. However, a number of transition countries do not have any precise policy or concept for decentralization. They seem to be conservative towards any other external efforts or initiatives with that respect. The situation is even more complicated by a higher level of corruption in public administration and high-rank public officials preponderantly pursuing their own -

2018 BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report

BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report 2018 The energy we produce serves to power economic growth and lift people out of poverty. In the future, the way heat, light and mobility are delivered will change. We aim to anchor our business in these changing patterns of demand, rather than in the quest for supply. We have a real contribution to make to the world’s ambition of a low carbon future. For a secure, affordable and sustainable energy future. bp.com/sustainability Introduction from our regional president Sustainability is at the heart of BP’s strategy. meeting the dual challenge that we all face Azerbaijan. We hit this important milestone in We believe that a long-term business can only today: how to deliver more of the energy our cooperation with the government, SOCAR and prosper if it is constantly striving to bring a growing world needs but with fewer other co-venturers as part of our long-term sustainable positive impact to the societies in greenhouse gas emissions. As a result of strategy and commitment to enhancing which it operates. these efforts we achieved more than 95,000 nationalization of staff and development of our tonnes of sustainable GHG emissions workforce. For more than 26 years that we have been in reductions in our operations in Azerbaijan in Azerbaijan, BP has been committed to As a good corporate citizen and responsible 2018, which is over 75% more than in 2017. conducting a safe and sustainable business that neighbour of the communities where we At the same time, despite the significant benefits all our stakeholders and the wider operate, we continued our efforts in creating reduction in flaring from the Deepwater society.