3 World War II Sirens and Blackouts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 ECT Annual Report

ECT Annual Report 2019 1 HE TAU WHAKATUTUKI A YEAR OF ACTION 2019 ANNUAL REPORT TE PŪRONGO Ā TAU 2019 2 Section Name ECT Annual Report 2019 3 KA MAHI NGĀTAHI, KIA TIPU, KIA PUĀWAI TE HĀPORI. TOGETHER, CREATING A POSITIVE, PROSPEROUS AND ATTRACTIVE COMMUNITY Image credit: Damon Meade PRIORITY TWO: GROWING OUR REGIONAL ECONOMY CONTENTS TE WHAKAURU RAWA, TAIMA HOKI HEI WHAKATIPU I TE OHANGA A TE ROHE ME TE GDP A IA TANGATA PART B - TOURISM IN TAIRĀWHITI 52 INTRODUCTION Tairāwhiti Gisborne 54 The year at a glance 6 TRENZ and eXplore 56 Our purpose 8 Dive Tatapouri 57 Our structure 9 Tairāwhiti Gisborne Spirited Women All Women's Adventure Race 58 Chairman’s and Chief Executive’s message 10 Maunga Hikurangi Experience 59 Your Eastland Community Trust Trustees 14 Asset Library 60 Activate Tairāwhiti Board Members 16 Waka Voyagers Tairāwhiti 61 Community wellbeing 18 2018/2019 Cruise season 62 Cycle Gisborne 63 PRIORITY ONE: MAINTAINING A FINANCIALLY SUSTAINABLE TRUST i-SITE 64 WHAINGA MATUA TAHI: TEWHAKAŪ TARATI WHAI RAWA 22 Railbike Adventures 65 Eastland Community Trust Financial Highlights 24 Eastern Regional Surf Lifesaving Championship 66 Eastland Group 26 Maunga to Moana 67 Te Ahi O Maui 27 Eastland Port 28 Eastland Network 29 PRIORITY THREE: SUPPORTING OUR COMMUNITY WHAINGA MATUA TORU: TE TAUTOKO A-HAPORI, ANA RŌPŪ ME ANA RAWA 68 Smart Energy Solutions 70 PRIORITY TWO: GROWING OUR REGIONAL ECONOMY Te Hā Sestercentennial Trust 71 TE WHAKAURU RAWA, TAIMA HOKI HEI WHAKATIPU I TE OHANGA 72 A TE ROHE ME TE GDP A IA TANGATA Hospice Tairāwhiti -

East Coast Inquiry District: an Overview of Crown-Maori Relations 1840-1986

OFFICIAL Wai 900, A14 WAI 900 East Coast Inquiry District: An Overview of Crown- Maori Relations 1840-1986 A Scoping Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal Wendy Hart November 2007 Contents Tables...................................................................................................................................................................5 Maps ....................................................................................................................................................................5 Images..................................................................................................................................................................5 Preface.................................................................................................................................................................6 The Author.......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................ 6 Note regarding style........................................................................................................................................... 6 Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Property Guide, January 30, 2020

gisborneCOMMERCIAL • RESIDENTIALproperty • RURAL GISBORNE MREINZ • Thursday, January 30, 2020 Exceptional 6 3 2 BRONWYN KAY AGENCY LTD. MREINZ LICENSED UNDER THE REA 2008 2 gisborne property Gisborne's Largest Independent Agency New Listing Exceptional 6 3 2 4 Silverstone Place This contemporary home offers four bedrooms plus two offices. If you have a large family, appreciate quality and work View Sun 2nd Ref BK2363 from home then this is possibly the home for you. 1:00-1:30pm Generous garaging, internal access. Agent Bronwyn Kay A private setting of 1746sqm with established trees and a courtyard to be the envy of many. A rural outlook giving you Auction Thu 5th Mar at 0274 713 836 the impression of being in the country. 1:00pm (Unless sold prior) Close to Schools and the Gisborne Hospital. This home has it all. Pure Beach Front 4 2 2 18 Pare Street This wave-like home is nestled amongst native plants creating a natural environment on the East Coast of Gisborne. View Sun 2nd Ref BK2345 The more than generous bedrooms allow for extended family or long term guests. Large sliding doors open to a private 12:00-12:30pm deck overlooking the ocean. Positioned well for early morning sunrise (The first City to see the sun). The large kitchen Agent Bronwyn Kay dining area invites you to entertain or just sit and ponder the beginning of the day. A great spot for surfing and long Auction Thu 27th Feb at 0274 713 836 leisurely walks upon the sand. Living in a caring community just minutes from the city, with the walkway/cycle way 1:00pm available for those that choose to walk or cycle and for those with school age children, Wainui Beach school is just (Unless sold prior) metres away. -

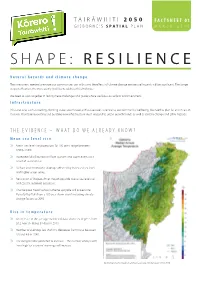

Shape: Resilience

TAIRĀWHITI 2 0 5 0 FACTSHEET 01 GISBORNE’S SPATIAL PLAN MARCH 2019 SHAPE: RESILIENCE Natural hazards and climate change The investment needed to ensure our communities can withstand the effects of climate change and natural hazards will be significant. The longer we put off action, the more costly it will be to address this challenge. We need to work together in facing these challenges and guide where we focus our efforts and investment. Infrastructure Infrastructure, such as roading, drinking water, stormwater and wastewater, is central to our community wellbeing. We need to plan for and invest in it wisely. Maintaining existing and building new infrastructure must respond to urban growth trends as well as climate change and other hazards. THE EVIDENCE – WHAT DO WE ALREADY KNOW? Mean sea level rise Mean sea level rise projections for 100 years range between » 0.55m-1.35m Increased risk of inundation from tsunami and storm events as a » result of sea level rise. Surface and stormwater drainage affected by increased sea level » and higher water tables. Restriction of Waipaoa River mouth possible due to sea level rise » and coastal sediment processes. The Waipaoa Flood Control Scheme upgrade will protect the » Poverty Bay Flats from a 100-year storm event including climate change factors to 2090. Rise in temperature An increase in the average number of days above 25 degrees from » 24.2 now to about 34 days in 2040. Number of evenings less than 0°C decreases from 8.5 to between » 3.6 and 4.6 in 2040. Fire danger index predicted to increase – the number of days with » ‘very high’ or ‘extreme’ warnings will increase. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Chairperson’s Report 02 reports 02 Chief Executive’s Report 03 Our Board 04 our people 04 Our Team 05-06 Our Partners & Sponsors 07 statistics 08 At a Glance 08-09 Coaching 10-11 community sport 10 Officials 12 Volunteers 13 Community Development Code Forums 14 contents Touch Rugby 15 Bikes in Schools 16 Sport on the Move 17 Top Up Scheme 17 Talent Development 18 Step2Move 19 active health 19 Green Prescription 20-21 Active Families 22 Active Mokopuna 23 active youth 23 Primary/Intermediate School 24 Crackerjack Kids 25 KiwiSport 26-27 Secondary School 28 Signature Events 29-30 events 29 Partner Events 31-32 Compilation Report 33 PERFORMANCE 33 Approval of Performance Report 34 Entity Information 35 REPORT 00 Statement of Service Performance 36 Statement of Performance 37 Statement of Financial Position 38 Statement of Cash Flow 39 Statement of Accounting Policies 40 Photography Credit Notes to the Financial Report 41-47 A special thank you to The Gisborne Herald for Depreciation Schedule 48-49 providing many of the Independent Auditor’s Report 50-52 photos in this report. from the chair PRUE YOUNGER This year as I celebrate 10 years as the Chair of Sport Gisborne Tairawhiti, I can reflect that every year seems to have been filled with new ideas, new strategies and new regional challenges that we have been involved with to benefit the health and wellbeing of our community. Memories of this period can only be positive and the organisation has gone from strength to strength. This has been in the majority due to the outstanding contribution of our departing CEO, Brent Sheldrake who left the organisation in August to work for Sport New Zealand where he remains closely linked to SGT as With the changing of the guard, we welcomed in our Area Manager. -

Property Guide, February 18, 2021

Thursday, February 18, 2021 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 108A ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO a sunny gem 90m² 455m² 2+ 1 1 What a fabulous property, there is just so much to love about 108A Ormond Road, Whataupoko; there is something for everyone with this sweetie. LAST CHANCE • LOCATION: close to Ballance • JUST EASY: a pocket-size section that St Village with all the day to day packs a lot of punch. A manageable conveniences you may need – a super 455m2, with dual parking options given handy convenient location; the corner site. Nicely fenced, some • A LITTLE RETRO: a classic 1950s. Solid gardens in place, and fully fenced out structure, native timberwork and hardy back for your precious pets, or little weatherboard exterior. Good size ones; lounge, and kitchen/dining, and, both • EXTRAS: a shed for ‘tinkering’, and an bedrooms are double. Lovely as is, but outdoor studio for guests, hobbies, or with room to add value; maybe working from home? And Investors, if you are looking for a rock-solid property with IMPECCABLE tenants – get this one to the top of your list. tender Closes: 12pm Tuesday 23rd February 2021 (unless sold prior) VIEWING: Saturday 1pm-1:30pm Or call Tracy to view 70 ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO it’s the location… 152m² 522m² 4 1+ 1 As a buyer you know it’s all about LOCATION & OPPORTUNITY, and they say “buy the worst house in the best street” to get ahead in the property game. LAST CHANCE To be fair, potentially not the ‘worst house’ but definitely one that piques the curiosity; and it’s located in a ‘best street’ a fabulous part of Gisborne – WHATAUPOKO. -

Local Government on the East Coast

Local Government on the East Coast August 2009 Jane Luiten A Report Commissioned by HistoryWorks for the Crown Forestry Rental Trust 1 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 5 Local Government.................................................................................................................. 5 Project Brief ........................................................................................................................... 7 Statements of Claim ............................................................................................................... 9 The Author ........................................................................................................................... 11 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 13 Part One: The Historical Development of Local Government................................................. 27 1. Local Government in the Colonial Context: 1840-1876................................................... 28 1.1 Introduction.............................................................................................................. 28 1.2 Local Government in the Crown Colony, 1840-1852.............................................. 29 1.3 Constitution Act 1852 .............................................................................................. 35 1.4 Financing -

Schedule G15 : Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies

Schedule G15 : Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies Note: This Schedule was formerly Schedule 1 of the Regional Freshwater Plan. Schedule G15 contains a list of Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies. There are five parts to the Schedule. Schedule G15A contains the nationally and regionally significant habitats and migratory habits of native fish. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within; the name of the river/stream or lake and/or stream tributary schedule and a list of the native fish that are known to use the waterbodies for habitat and migration. The schedule was developed based on the work undertaken under the RIVAS studies identifying nationally and regionally significant native fish habitat. Schedule G15B contains the additional key habitats for Long Finned Eel – a nationally threatened native species which the Gisborne region is recognised as providing a national stronghold for populations. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within and the name of the river and/or stream tributary schedule where long finned eel populations are known to exist. Schedule G15C contains the freshwater habitats of threatened indigenous flora and fauna. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within; the name of the river/stream or lake/wetland/river mouth and the threatened species present in the waterbody. Schedule G15D contains the known whitebait spawning sites in the region. The schedule contains the catchment, river or stream and location of the spawning site. Schedule G15E contains the important habitats of trout. The schedule contains the catchment, river or stream. It also outlines whether the stream is a nationally, regionally or locally significant habitat. -

Research Report 3: Waimata River Sheridan Gundry

TE AWAROA: RESTORING NEW ZEALAND RIVERS RESEARCH REPORT 3: WAIMATA RIVER SHERIDAN GUNDRY THE WAIMATA RIVER: SETTLER HISTORY POST 1880 The Waimata River – Settler History post 1880 Sheridan Gundry, Te Awaroa Project Report No. 3 Land within the Waimata River catchment, comprising about 220 square kilometres1, began to be available for purchase after the passing of the Native Lands Act 1865 and subsequent land surveys and issuing of legal Crown title. The lower reaches of the Waimata River – including parts of the Kaiti, Whataupoko and Pouawa blocks – were the first to go into European ownership from around 1880, when John and Thomas Holden bought the 7000 acre Rimuroa block; the Hansen brothers bought about 8000 acres comprising Horoeka, Maka and Weka; Bennet bought the 1100 acre Kanuka block; and Charles Gray, the Waiohika block. The next year, in 1881, the Kenway brothers bought the 3000-acre Te Pahi further upriver. The Kenways gave the property the name Te Pahi, meaning The End, because at the time it was at the end of the road with nothing beyond.2 This soon changed with further purchases of Maori land beyond Te Pahi continuing through to the late 1890s. Further land became available in the south, east and north Waimata with the New Zealand Native Land Settlement Company offering about 20,000 acres for sale in late 1882. The blocks “conveyed to the company” were approved by the Trust Commissioner and titles were to be registered under the Land Transfer Act.3 The areas involved were Waimata South, 9,555; Waimata East, 4,966; Waimata North, 4,828. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

3052 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. '113 MILITARY AREA No. 7 (NAPIER)-oontinued. MILITARY AREA No. 7 (NAPIER)-oontinuea. 522853 Chrystal, ,Gerald Terawhiti, farmer, Tutira. 497000 Coppin, Ezra Noah, teacher, c/o Empire Hotel. 625399 Cibilich, Anton Matov, labourer, " Glenburn " Station, 569693 Corbett, Arthur, labourer, Bay View. Private Bag, Masterton. 543279 Corbett, Clarence George, tallow foreman, 6 Clifford St., 485400 Clanachan, James, Y.M.C.A. secretary, Y.M.C.A., Bartletts. · Gisborne. · 594150 Clapcott, · Wilfrid Henry, signal adjuster, Ackinson St., 481900 Corbett, Reginald Samuel, fertilizer department, 46 Somer ' Woodville. ville St., Wairoa. 485386 Clapham, Stanley Lewis, P. and T. clerk, 4 Birrell St., 500118 Corbett, Richard Frank Louis, bulldozer~driver, c/o Post Gisborne. office, Bay View. 462135 Clapp, James Henry, wool-store employee, Westshore Ex- 481903 Corbett, William Flurence, freezing-works employee, 11 tension. , Brian Ave., Wairoa. 539376 Clapperton, James Alfred, farm-manager, Guppys Rd., 508989 Corlett, FredrickJames, barman, 800 Gordon Rd., Hastings. Taradale. 500127 Corn, Israel, chemist, 117 Iranui Rd., Gisborne. 468829 Clare, George Stanley Gordon, civil servant, 609 Massey St., 469746 Cornish, Kenneth Edward, wool-valuer, 18 Roslyn Rd. Hastings. 571672 Corry, Francis Ernest Leeming, bank officer, 177 Dixon St., 544124 Clark, Francis Horsman, linesman, c/o P.W.D., Tuai. Masterton. 545733 Clark, James, N.Z.R. ganger, 21 Awapuni Rd., Gisborne. 543024 Corskie, Arthur Alick George, assistant manager, 31 Pownall 545732 Clark, James, waterside worker, 2.A. Havelock Rd. St., Masterton. 487456 Clark, Reginald Allan, transport _driver, 606 King St., 481442 Cotter, Gordon Pierce, electrician, Oxford St., Martin Hastings. borough. 58582t Clark, Sydney William, driver-mechanic, 43 Campbell St., 585795 Cotter, Spencer Harold, dairy-farmer, 158 Renall St., 523758 Clark, William, contractor ploughman, Park Rd., Hastings. -

Gizzybus Timetable Download PDF File (315.9

Bus stop T S Bus stop - route point ON T Y A Direction of travel T POTAE AVE Lytton S Rest homes between 8.45am - 3.30pm West S D T RLE S A A R Y ST A EMIL H P C U A R P Medical centres D Mangapapa R E School ANGA PL M Lytton High M Timetable School Y ALR D FERGUSSON DR T HAN S E E T H S S T R D R Botanical D D ALBE R Y R Gardens Te Hapara E L School N MILL A Girls High T S School T HERBERT S LI E RA T S S I D N T GLA DE DS Y S TON OB B E C HAIG ST BULWER RD RD R Co DE untd own T S Pak n Elgin Save School RVON A Gisborne T S RD ananga S CHILDER Te W T ARN C o Aotearoa S Intermediate A A School T S T AR Court T BRIGHT EL E S O E House T P OW L T KA S H UTI E A ST S ELL ST U BIRR HO M O T S U AWAPUNI RD C T S D R SALISBURY RD Gisborne NT E K ON Airport T T Y L CITY – HOSPITAL – TE HAPARA – CITY CITY – ELGIN – HOSPITAL – CITY Bright St Ballance Hospital Te Wiremu Bright St Bright St YMCA Elgin Hospital Bright St 1A Terminal Street Rest Home Terminal 2B Terminal Shops Terminal AM 7.45 7.55 8.05 8.20 8.30 AM 7.00 7.05 7.15 7.30 7.45 AM 9.45 9.55 10.05 10.20 10.30 AM 8.45 8.50 9.00 9.15 9.30 AM/PM 11.45 11.55 12.05 12.20 12.30 AM 9.45 9.50 10.00 10.15 10.30 PM 1.45 1.55 2.05 2.20 2.30 AM 10.45 10.50 11.00 11.15 11.30 PM 3.45 3.55 4.05 4.20 4.30 AM/PM 11.45 11.50 12.00 12.15 12.30 GizzyBus services PM 5.10 5.15 5.20 5.30 5.35 PM 12.45 12.50 1.00 1.15 1.30 CITY – ELGIN – CITY PM 1.45 1.50 2.00 2.15 2.30 in Gisborne city PM 2.45 2.50 3.00 3.15 3.30 Bright St Desmond Rugby Elgin Bright St PM 5.15 5.20 5.25 5.30 5.45 1B Terminal Road Park Shops -

November 2020 RESIDENTIAL SALES GISBORNE

market facts november 2020 RESIDENTIAL SALES GISBORNE SUBURB 2017 RV PRICE RV/SP % BEDS FLOOR LAND BEACH $635,000 $1,100,000 73.23% 3 210 1213 BEACH $1,069,000 $1,500,000 40.32% 3 90 1528 BEACH $418,000 $930,000 122.49% 3 171 526 BEACH – AVERAGE SALE PRICE % OVER 2017 RV 76.68% CITY $225,000 $420,000 86.67% 3 122 317 CITY $267,000 $440,000 64.79% 3 150 556 CITY $212,000 $480,000 126.42% 2 85 364 CITY $230,000 $800,000 247.83% 3 182 APTMENT CITY $340,000 $365,000 7.35% 3 150 APTMENT CITY CENTRAL – AVERAGE SALE PRICE % OVER 2017 RV 106.61% INNER KAITI $182,000 $347,000 90.66% 2 100 CROSS-LEASE INNER KAITI $491,000 $940,000 91.45% 4 167 2120 INNER KAITI $281,000 $550,000 95.73% 3 130 717 INNER KAITI $209,000 $605,000 189.47% 3 110 670 INNER KAITI $650,000 $1,034,500 59.15% 5 280 2023 INNER KAITI – AVERAGE SALE PRICE % OVER 2017 RV 105.29% KAITI $199,000 $375,000 88.44% 2 80 859 KAITI $185,000 $435,000 135.14% 2 132 635 KAITI $562,000 $950,000 69.04% 3 220 825 KAITI $124,000 $350,000 182.26% 3 94 658 KAITI $259,000 $455,000 75.68% 3 103 1012 KAITI – AVERAGE SALE PRICE % OVER 2017 RV 110.11% LYTTON WEST $384,000 $625,000 62.76% 2 119 555 LYTTON WEST $442,000 $780,000 76.47% 3 150 533 LYTTON WEST $387,000 $655,000 69.25% 3 123 400 LYTTON WEST $384,000 $833,000 116.93% 2 123 684 LYTTON WEST – AVERAGE SALE PRICE % OVER 2017 RV 81.35% tracy real estate 121 Ormond Road, Gisborne P 06 929 1933 | M 027 553 5360 | E [email protected] Tracy Bristowe, AREINZ | Licensed Real Estate Agent REA 2008 www.tracyrealestate.co.nz PAGE 1 OF 3 market