Lesson Eleven: the Processes of Amending Or Adopting a Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Signers of the U.S. Constitution

CONSTITUTIONFACTS.COM The U.S Constitution & Amendments: About the Signers (Continued) The Signers of the U.S. Constitution On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention came to a close in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were seventy individuals chosen to attend the meetings with the initial purpose of amending the Articles of Confederation. Rhode Island opted to not send any delegates. Fifty-five men attended most of the meetings, there were never more than forty-six present at any one time, and ultimately only thirty-nine delegates actually signed the Constitution. (William Jackson, who was the secretary of the convention, but not a delegate, also signed the Constitution. John Delaware was absent but had another delegate sign for him.) While offering incredible contributions, George Mason of Virginia, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts refused to sign the final document because of basic philosophical differences. Mainly, they were fearful of an all-powerful government and wanted a bill of rights added to protect the rights of the people. The following is a list of those individuals who signed the Constitution along with a brief bit of information concerning what happened to each person after 1787. Many of those who signed the Constitution went on to serve more years in public service under the new form of government. The states are listed in alphabetical order followed by each state’s signers. Connecticut William S. Johnson (1727-1819)—He became the president of Columbia College (formerly known as King’s College), and was then appointed as a United States Senator in 1789. -

U.S. Constitution Role Play Who Really Won?

handout U.S. Constitution Role Play Who Really Won? How did the Writers of the U.S. Constitution decide the issues that you debated in class? Find the actual outcome of these questions by looking in the Constitution. On a separate sheet of paper, for each of the following, indicate 1. What the class Constitutional Convention decided; and 2. What the actual U.S. Constitutional Convention decided. The parentheses after each question indicate at least one section of the Constitution that will help you find an answer. 1a Should slavery be legal in any of the United States? (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1) 1b. Should the slave trade continue to be allowed? (Article I, Section 9, Clause 1) 1c. Should northerners be forced to turn over runaway (fugitive) slaves to their owners? (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3) 2. Will it be legal for state legislatures to pass laws allowing debts to be paid “in kind”? (Article I, Sec- tion 10, Clause 1) 3. Should bonds issued during the Revolutionary War be paid back? (Article VI, Clause 1) 4. Who should be allowed to vote in general elections? (The Constitution says nothing about who shall vote, therefore who could vote was left up to individual states. At the time, no states allowed women or enslaved people to vote; many states had laws requiring individuals to own a certain amount of property before they could vote. Most states did not allow free blacks to vote.) 5. Conclusion: In your opinion, which social group or groups won the real Constitutional Convention? Explain your answer. -

The Constitutional Quest Is an Easy and Fun Way to Explore Our Museum

www.constitutioncenter.org www.constitutioncenter.org 215-409-6600 215-409-6600 Philadelphia, PA PA Philadelphia, Answers: 6. Because Americans felt that black robes are more suitable for a Independence Mall Mall Independence democratic nation and Americans wanted to distinguish them- selves from the red robes the British wore. National Constitution Center Center Constitution National 1. Mickey Mouse 7. books 2. New York Answers on back page. page. back on Answers 8. 1966 3. [Your choice] 9. The state. 4. [Your choice] museum. See how many you can find! find! can you many how See museum. 10. Richard Bassett, Gunning Bedford Jr., Jacob Broom, John 5. Preserve, protect, and defend Dickenson, or George Reed numbered arrows and solve mysteries throughout the the throughout mysteries solve and arrows numbered explore our museum. Follow Follow museum. our explore the clues that match the the match that clues the The Constitutional Quest is an an is Quest Constitutional The easy and fun way to to way fun and easy 1. You may recognize this cartoon charac- 5. Take the Presidential Oath and list the three promises 6. Try on a black robe like the ones judges wear. ter, but did you know that his original you, as President, make. Why are all judges’ robes black? name was “Steamboat Willie”? ___________, __________________, ________________ Find him by looking for big ears! ____________________________________ What’s his name? ____________________________________ ______________________ 3 4 2 5 6 7. In this exhibit something is piled up 2. Find the state Constitution from one of the high that’s also used in school. -

The Beauty of the Historic Brandywine Valley Proquest

1/10/2017 The beauty of the historic Brandywine Valley ProQuest 1Back to issue More like this + The beauty of the historic Brandywine Valley Kauffman, Jerry . The News Journal [Wilmington, Del] 04 Sep 2012. Full text Abstract/Details Abstract Translate The Victorian landscape movement was popular and in 1886 Olmstead recommended that the Wilmington water commissioners acquire the rolling creek-side terrain as a park to protect the city's water supply. Full Text Translate The landmark decision by the Mount Cuba Foundation and Conservation Fund to acquire the 1,100-acre Woodlawn Trustees property for a National Park was a watershed for the historic Brandywine Valley. Coursing through one of the most beautiful landscapes in America, no other river of its size can rival the Brandywine for its unique contributions to history and industry. The Brandywine rises in the 1,000-feet high Welsh Mountains of Pennsylvania and flows for 30 miles through the scenic Piedmont Plateau before tumbling down to Wilmington. The river provides drinking water to a quarter of a million people in two states, four counties, and 30 municipalities. Attracted to the pastoral countryside and nearby jobs in Wilmington and Philadelphia, 25,000 people have moved here since the turn of the century. Its watershed is bisected by an arc traced in 1682 by William Penn that is the only circular state boundary in the U.S. Though 90 percent of the catchment is in Pennsylvania, the river is the sole source of drinking water for Wilmington, Delaware's largest city. Delaware separated from Pennsylvania in 1776, but the two states remain joined by a common river. -

JACOB BROOM a Biographical Sketch by Nuala M. Drescher

JACOB BROOM A Biographical Sketch by Nuala M. Drescher Hagley Museum July 1959 JACOB BROOM Jacob Broom had a varied and successful life and career, centered about the ever-growing borough of Wilmington, Delaware. He began his business career as a surveyor of land and conveyor of title; took an active role in the political life of his city and colony; supported the Revolution; and continued his interest in local, state and national politics following tne suspension of hostilities. Born and educated in Wilmington, Broom rapidly rose to prominence in the business world and died in Philadelphia in 1810 after a brief illness, while in that city on a business trip relative to his merchant interests. Jacob Broom was tne son of Janes Broom and Esther Willis Broom. His father was a native Delawarean, a blacksmitu who had turned farmer. His will reveals that wnile ne was considered to be a "yeoman", ne was actually a man of considerable property.^" Broom's mother, Esther Willis, was the daughter of John and Mary Willis of Thornbury, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Mr. Willis was a member of the Society of Friends, and as his daugnter held similar religious views, it is not surprising that no record can be found of the baptism of her eldest child, Jacob, bom in Wilmington in 1752.2 Following the tradition of the area, Broom was educated at home until about his thirteenth year when he "enjoyed the advantage of substantive 3 schooling, both secular and religious" at the Old Academy on Market Street. He was trained as a surveyor and conveyor of title; and in 1772 he was advertising in the Pennsylvania Gazette that he had been regularly instructed in the practice of surveying and conveying and had set up an office on"the 4 corner of Market Street and Third Street, in the Borough of Wilmington." At -2- the same time, he advertised that he acted as an investor in real estate, an indication of the already blossoming diversification of his business interests and abilities. -

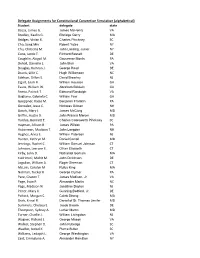

Delegate Assignments for Constitutional Convention Simulation (Alphabetical) Student Delegate State Bozza, James G

Delegate Assignments for Constitutional Convention Simulation (alphabetical) Student delegate state Bozza, James G. James McHenry VA Bradley, Kaelin G. Elbridge Gerry MA Bridges, Vivian K. Charles Pinckney SC Cho, Sung Min Robert Yates NY Chu, Christina M. John Lansing, Junior NY Cone, Jacob T. Richard Bassett DE Coughlin, Abigail M. Gouvernor Morris PA Deholl, Danielle L. John Blair VA Douglas, Kamran J. George Read DE Dravis, Lillie C. Hugh Williamson NC Edelson, Dillon S. David Brearley NJ Elgart, Leah R. William Houston GA Evans, William W. Abraham Baldwin GA Femia, Patrick T. Edmund Randolph VA Gagliano, Gabriela C. William Few GA Goeppner, Kacie M. Benjamin Franklin PA Gonzalez, Jesse C. Nicholas Gilman NH Gosch, Mary I. James McClurg MD Griffin, Austin D. John Francis Mercer MD Hardee, Bennett E. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney SC Hayman, Allison B. James Wilson PA Huberman, Madison T. John Langdon NH Hughes, Anna E. William Paterson NJ Hunter, Kathryn M. Daniel Carroll MD Jennings, Rachel C. William Samuel Johnson CT Johnson, Lee-ann E. Oliver Ellsworth CT Kirby, John D. Nathanial Gorham MA Kudrimoti, Mohit M. John Dickinson DE Logsdon, William A. Roger Sherman CT McLain, Carolyn M. Rufus King MA Norman, Tucker K. George Clymer PA Pace, Gracen T. James Madison, Jr VA Page, Evan P. Alexander Martin NC Page, Madison N. Jonathan Dayton NJ Pitner, Mary K. Gunning Bedford, Jr. DE Pollock, Morgan C. Caleb Strong MA Shah, Krinal R. Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer MD Summers, Chelsea E. Jacob Broom DE Thompson, Sydney A. Luther Martin MD Turner, Charlie J. William Livingston NJ Wagner, Richard J. -

High School | 9Th–12Th Grade

High School | 9th–12th Grade American History 1776The Hillsdale Curriculum The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum 9th–12th Grade HIGH SCHOOL American History 2 units | 45–50-minute classes OVERVIEW Unit 1 | The American Founding 15–19 classes LESSON 1 1763–1776 Self–Government or Tyranny LESSON 2 1776 The Declaration of Independence LESSON 3 1776–1783 The War of Independence LESSON 4 1783–1789 The United States Constitution Unit 2 | The American Civil War 14–18 classes LESSON 1 1848–1854 The Expansion of Slavery LESSON 2 1854–1861 Toward Civil War LESSON 3 1861–1865 The Civil War LESSON 4 1865–1877 Reconstruction 1 Copyright © 2021 Hillsdale College. All Rights Reserved. The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum American History High School UNIT 1 The American Founding 1763–1789 45–50-minute classes | 15–19 classes UNIT PREVIEW Structure LESSON 1 1763–1776 Self-Government or Tyranny 4–5 classes p. 7 LESSON 2 1776 The Declaration of Independence 2–3 classes p. 14 LESSON 3 1776–1783 The War of Independence 3–4 classes p. 23 LESSON 4 1783–1789 The United States Constitution 4–5 classes p. 29 APPENDIX A Study Guide, Test, and Writing Assignment p. 41 APPENDIX B Primary Sources p. 59 Why Teach the American Founding The beginning is the most important part of any endeavor, for a small change at the beginning will result in a very different end. How much truer this is of the most expansive of human endeavors: founding and sustaining a free country. The United States of America has achieved the greatest degree of freedom and prosperity for the greatest proportion of any country’s population in the history of humankind. -

The Continental Army At

The Continental Army at “Headquarters Towamensing” October 8-16, 1777 From the chapter “A Respite from A Revolution” in the book “Paper Quill and Ink, The Diaries of George Lukens 1768-1849 Towamencin Township Quaker - Farmer - Schoolmaster - Abolitionist, And A History of Towamencin Township” by Brian Hagey published 2016 by the Mennonite Historians of Eastern Pennsylvania. Copyright © 2016 Brian Hagey. Edition Two or years a sign hung on the wall beside the front desk of a hotel along the Sumneytown Pike in Kulpsville that read "At this spot on July 4, 1776 not a damn thing happened." F The satirical phrase with roots in the Bicentennial Celebration is a humorous and crude reminder that nothing noteworthy happened on that quiet summer day in pastoral Towamencin Township, as compared to a world-changing event that took place the same day 23 miles to the south in colonial Philadelphia. After much debate among the delegates and several rewrites by Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, the Second Continental Congress approved a recent congressional vote to declare independence from King George III of Great Britain. On July 4, 1776, the birth of our new nation was announced and Towamencin’s future, as well as the rest of the world, was soon to be very much affected. A mile marker along the Sumneytown Pike in Kulpsville states 23 miles to Philadelphia. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Philadelphia was the largest city in the British colonies; an important marketplace for Towamencin farmers as well as the birthplace of our nation. The war that began in Lexington, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775, over a year before independence was declared, eventually made its way to Towamencin. -

America's Founding Fathers -- Who Are They? Thumbnail Sketches of 164 Patriots

AMERICA’S FOUNDING FATHERS Who are they? Thumbnail sketches of 164 patriots JACK STANFIELD Universal Publishers USA • 2001 America's Founding Fathers -- Who are they? Thumbnail sketches of 164 patriots Copyright © 2001 Jack R. Stanfield All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except in case of review, without the prior written permission of the author. Author’s Note: The information is accurate to the extent the author could confirm it from readily available sources. Neither the author nor the publisher can assume any responsibility for any action taken based on information contained in this book. Universal Publishers/uPUBLISH.com USA • 2001 ISBN: 1-58112-668-9 www.uPUBLISH.com/books/stanfield.htm To my wife Barbara who inspired this book, and without whose patience and encouragement, it would not have been completed. Content INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 SETTING THE STAGE 10 SKETCHES OF THE FOUNDING FATHERS 23 CHAPTER 2 FOUNDING FATHERS FROM CONNECTICUT 24 Andrew Adams, Oliver Ellsworth, Titus Hosmer, Samuel Huntington, William Samuel Johnson, Roger Sherman, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott CHAPTER 3 FOUNDING FATHERS FROM DELAWARE 32 Richard Bassett, Gunning Bedford, Jacob Broom, John Dickinson, Thomas McKean, George Read, Caesar Rodney, Nicolas Van Dyke CHAPTER 4 FOUNDING FATHERS FROM GEORGIA 39 Abraham Baldwin, William Few, Button Gwinnett, Layman Hall,William Houstoun, -

Delaware Role-Min

Delaware Day 4th Grade Competition Lesson Three What was Delaware’s Role? Students will be able to: Identify the five Delawareans who attended the federal convention which resulted in the Constitution and explain why these particular men might have been chosen. (Panel 2:1) Explain when and where Delaware ratified the proposed Constitution (Panel 2:2) Identify how many Delawareans were involved in voting to ratify the Constitution, where they were from and whether the vote was unanimous. (Panel 2:3) Express an opinion regarding why Delawareans should be proud that we were the first state to ratify the Constitution. (Panel 2:4) This lesson contains information, resources and ideas to help students understand Delaware’s role in the creation and ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Teachers will determine best practices and methods for instruction. 1. Introductory Activity for “The Delaware Five” (a phrase coined by students from Brader Elementary School in Newark) a. Distribute Document 1: What Makes A Good Leader? and give students time to write their answers. On the board, list their answers. (If you wish, you can make two columns – one for positive qualities and one for negative qualities.) b. Write the following names on the board: Richard Bassett, Gunning Bedford, Jr., Jacob Broom, John Dickinson and George Read. Explain that these five men from Delaware were chosen to go to Philadelphia to help write the Constitution. Documents 2a, 2b, 2c, 2d, 2e: The Delaware Five include one signer per page. Create groups and distribute one document per group. Ask the students to make a list of reasons why their leader might have been chosen to attend such an important convention. -

PEAES Guide: Historical Society of Delaware

PEAES Guide: Historical Society of Delaware http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/dhs.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One Historical Society of Delaware 505 Market Street, Wilmington, DE Phone: (302) 655-7161 http://www.hsd.org/library.htm Contact Person: Constance Cooper, [email protected] Overview: The Historical Society of Delaware’s, founded in 1864, holds over 1 million manuscript documents covering the period of this study. The diverse collections are strongest for early Wilmington and New Castle County merchants and millers. HSD’s collections on Brandywine Mills are extensive for the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and strong on mercantile activity, agriculture (including a considerable number of valuable diaries), and transportation. Finally, the HSD holds a significant number of late eighteenth and nineteenth century general store records. HSD does not have many finding aids or indexes to collections; however, searches of the card catalog will yield important sources and connections. Also please see: Carol E. Hoffecker, Delaware: A Bicentennial History (New York, 1977); J. Thomas Scharf, History of Delaware, 1609-1888, 3 vols. (Philadelphia, 1888); and M. McCarter and B. F. Jackson, Historical and Biographical Encyclopedia of Delaware (Wilmington, 1882). RODNEY FAMILY HSD holds an extensive collection of papers relating to Thomas Rodney (1744-1811), many of which have changed names over time. At HSD the current Rodney Collection. (ca. 24 boxes) is the same as the H.F. Brown Collection. It contains the papers of both Caesar and Tomas Rodney. Elsewhere, researchers will find correspondence between Thomas and his brother Caesar (1728-84), and between Thomas and his son Caesar A. -

Act Electing and Empowering Delegates, 3 February 1787

Act Electing and Empowering Delegates, 3 February 1787 An ACT appointing Deputies from this State to the Convention, proposed to be held in the City of Philadelphia, for the Purpose of revising the Foederal Constitution. Whereas the General Assembly of this State are fully convinced of the Necessity of revising the Foederal Constitution, and adding thereto such further Provisions as may render the same more adequate to the Exigencies of the Union; and whereas the Legislature of Virginia have already passed an Act of that Commonwealth, appointing and authorizing certain Commissioners to meet, at the City of Philadelphia, in May next, a Convention of Commissioners or Deputies from the different States: And this State being willing and desirous of co-operating with the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the other States in the Confederation, in so useful a Design; Sect. 1. BE IT THEREFORE ENACTED by the General Assembly of Delaware, That George Read, Gunning Bedford, John Dickinson, Richard Bassett, and Jacob Broom, Esquires, are hereby appointed Deputies from this State to meet in the Convention of the Deputies of other States, to be held at the City of Philadelphia on the Second Day of May next. And the said George Read, Gunning Bedford, John Dickinson, Richard Bassett, and Jacob Broom, Esquires, or any Three of them, are hereby constituted and appointed Deputies from this State, with Powers to meet such Deputies as may be appointed and authorized by the other States to assemble in the said Convention at the City aforesaid, and to join with