Development and Testing of a Procedural Model for the Assessment of Human/Wetland Interaction in the Tobari System on the Sonoran Coast, Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Sonora, Mexico

52 A. J. van Rossem Occ. Papers Order FALCONIFORMES Birds of PreY Family Cathartidae American Vultures Coragyps atratus (Bechstein) Black Vulture Vultur atratus Bechstein, in Latham, Allgem. Ueb., Vögel, 1, 1793, Anh., 655 (Florida). Coragyps atratus atratus van Rossem, 1931c, 242 (Guaymas; Saric; Pesqueira: Obregon; Tesia); 1934d, 428 (Oposura). — Bent, 1937, 43, in text (Guaymas: Tonichi). — Abbott, 1941, 417 (Guaymas). — Huey, 1942, 363 (boundary at Quito vaquita) . Cathartista atrata Belding, 1883, 344 (Guaymas). — Salvin and Godman, 1901. 133 (Guaymas). Common, locally abundant, resident of Lower Sonoran and Tropical zones almost throughout the State, except that there are no records as yet from the deserts west of longitude 113°, nor from any of the islands. Concentration is most likely to occur in the vicinity of towns and ranches. A rather rapid extension of range to the northward seems to have taken place within a relatively few years for the species was not noted by earlier observers anywhere north of the limits of the Tropical zone (Guaymas and Oposura). It is now common nearly everywhere, a few modern records being Nogales and Rancho La Arizona southward to Agiabampo, with distribution almost continuous and with numbers rapidly increasing southerly, May and June, 1937 (van Rossem notes); Pilares, in the north east, June 23, 1935 (Univ. Mich.); Altar, in the northwest, February 2, 1932 (Phillips notes); Magdalena, May, 1925 (Dawson notes; [not noted in that locality by Evermann and Jenkins in July, 1887]). The highest altitudes where observed to date are Rancho La Arizona, 3200 feet; Nogales, 3850 feet; Rancho Santa Bárbara, 5000 feet, the last at the lower fringe of the Transition zone. -

Seventh Arizona .- A- in Each of the Other Election Pie- - '! Ç':,'',.: Cincts of the County

- 1 .147 .14 0.7 fo' 1! ,7 lot Zite order 4Tidettr. 14tv07 Nf NZ N01 V 7 2! PROFESSIONAL CARDS. ..m,.,w'Ww.oWso.,ftw,mw,i0.14w.em.o,..,,,m,,,,.,omo'.010 THE NOGALES COLD STORAGE, AMERICAN DRUG 2 OCTOBER 14, 1011. FRANK Ji DUFFY, STORE, Attorney-at-La- w L. E. CARRILLO, PROP. MS'S SAM:Ulan. Prop. 74 CONFICZ IN MCi NTYNN BOULDING Supervisors' Notice of Primary Gen- .,1GENTS Stenographer, Typewriter and Notary CON1PLETE ASSORTMENT eral Election FOR SCI1MTZ BEER OF 'il The poor.as well as the rich man's.depot. Public in Office Confectionery, Pure Drugs, WHERRAS: The Secretary of Arizona A Call and see me and get worth of money. Bond Bonds, has prepared and transmitted to the 41 the your K. Chemicals undersigned, the Clerk of the Board E. CUMMING. Perfumeries, of Supervisors of Santa Cruz County ii Telephone 371. P. O. Box 322. NOTARY PUBLIC and of Arizona a writ- Toilet Articles, etc. Patent Territory. notion in Æ Medicines. ing desiguating the offices for which 1T CD CD-AI- 3, - - - A TR, NOGALES, - - ARIZONA . r - L. : candidates are to be nominated at the 7.1 zi, ,s--O- 3.0v ensuing primary: S. F. NOON F. J. BARRY New Stock, Courteous Treatment. NOW, THEREFOnE: A primary Ili i election is hereby called in the several & of county, NOON BARRY OH PRICES ARE RIGHT.") precincts said under the Attorneys Counseders-at-La- w provisions of the law relating to pri- and mary elections, to wit; under the pro- NOGALES, ARIZONA Ili - visions of Chapter 24. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

115 Markow, TA and N. Maveety. Arizona State Wasserman & Koepfer

June 1985 Research Notes DIS 61 - 115 Markow, T.A. and N. Maveety. Arizona State Wasserman & Koepfer (1977) described character dis- University, Tempe, Arizona USNA. More placement for reproductive isolation between two character displacement for reproductive sibling species, D.mojavensis and D.arizonensis of isolation in the Mulleri complex. the mulleri complex of the repleta group. Zouros & d'Entremont (1980) demonstrated that the presence of D.arizonensis in the Sonoran part of the range of D.mojavensis is the cause of reproductive isolation between the two geographic races of D.mojavensis (race A in Sonora and race B in Baja California). The discovery of the third, undes- cribed sibling species, D. "species" Figure 1. Distribution of D.niojavensis and N" ("from Navojoa', Mexico) raises D. "species N" in Mexico and southwestern the question of additional character United States (after Heed 1982). displacement for sexual behavior in areas where this species is sympatric with the others. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the three species in Mexico and the United States; D. "species N" is sympatric with 4.'. D.mojavensis in southern Sonora and northern Sinaloa. There is no gene 'p flow between peninsular and mainland D.mojavensis. We tested for intensity of sexual isolation between D.mojavensis and D. "species" N" from sympatric and allopatric strains of both species. Experiments were conducted using procedures reported by Markow (1981) and Markow et al. (1983) in which 10 pairs from 2 different species are placed in an observation chamber for 1 hr. Results are shown in Table 1. When either D.mojavensis or D. -

Membership Register MBR0009

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF FEBRUARY 2020 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL DIST IDENT NBR CLUB NAME COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3000 015032 AGUA PRIETA MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 19 0 0 0 0 0 19 3000 015035 ARIZPE MEXICO B 1 4 03-2018 24 0 0 0 0 0 24 3000 015038 CABORCA MEXICO B 1 4 07-2019 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3000 015039 CANANEA MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 51 3 0 0 -8 -5 46 3000 015043 CIUDAD OBREGON MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 25 2 0 0 -1 1 26 3000 015047 CUMPAS MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 27 0 0 0 -2 -2 25 3000 015050 ENSENADA MEXICO B 1 4 12-2019 13 0 0 0 -1 -1 12 3000 015055 GUAYMAS MEXICO B 1 4 10-2019 19 0 0 0 0 0 19 3000 015057 HERMOSILLO MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 9 0 0 0 0 0 9 3000 015062 MAGDALENA MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 16 0 0 0 -1 -1 15 3000 015064 MEXICALI MEXICO B 1 4 03-2019 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 3000 015066 NACOZARI MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 16 0 1 0 0 1 17 3000 015067 NAVOJOA MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 25 3 0 0 -8 -5 20 3000 015069 NOGALES MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 22 6 0 0 -1 5 27 3000 015070 PLAYAS DE TIJUANA MEXICO B 1 4 01-2020 40 0 0 0 -5 -5 35 3000 015071 PUERTO PENASCO MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 18 0 0 0 -3 -3 15 3000 015076 SAN LUIS RIO COLO MEXICO B 1 4 08-2019 40 0 0 0 0 0 40 3000 015078 SONOYTA MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 14 0 0 0 -1 -1 13 3000 015079 TECATE MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 44 1 1 0 -7 -5 39 3000 015080 TIJUANA MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 32 1 0 1 -5 -3 29 3000 015081 TIJUANA LA MESA MEXICO B 1 4 02-2020 23 3 9 1 -16 -3 20 3000 036453 IMURIS MEXICO -

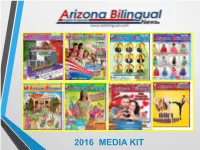

2016 MEDIA KIT a B O U T U S

2016 MEDIA KIT A b o u t U s Arizona Bilingual Newspaper is the only bilingual Over 2,000 points of publication locally owned. distribution in Tucson, Oro Valley, Marana, Connecting over 150,000 combined readers every Sahuarita, Green month through 25,000 printed editions, Internet, Valley, Rio Rico, Social Media and local community events. Nogales, Sierra Vista, Wilcox, Douglas and Arizona Bilingual Newspaper, has been contributed San Manuel. in outreach our bilingual and Hispanic community in Tucson, Southern Arizona and Sonora Mexico. Including 150 Circke K’s in Southern Our local community events mainly focusing in Arizona education, health, business, community and resources have been a great success for the last five years. Our mission is primarily to provide our community with articles of news with truthful reliable content, including education, business and community matters to inform and entertain our readers focusing in delivering the perfect message to our Hispanic Arizona Bilingual and bilingual community. Newspaper is also widely distributed South of the Border; in Arizona Bilingual Newspaper is a very well balanced 245 S. Plumer Ave Suite 14 Nogales, Hermosillo, publication linking our general to the Hispanic Tucson, AZ 85719 Puerto Peñasco/Rocky market obtaining excellent and satisfying results for Office (520) 305-4110 Point, Guaymas/San Fax (520) 829-7708 our new and stablished clients. Carlos, Obregon, Email: [email protected] Douglas/Agua Prieta, Website: If you give us the opportunity, we could also bring Magdalena, -

La Construcci6n De Una Agrociudad En El Noroeste De Mexico

SECOENClfi Secuencia (2006), 64, enero-abril, 113-143 Revistadehistorjaycienciassociales ISSN: 0186-0348, ISSN electrónico: 2395-8464 La construcci6n de una agrociudad en el noroeste de Mexico. Ciudad Obregon (1925-1960)* Mario Cerutti** ste trabajo inicial sobre Ciudad los sesenta del siglo xx- en eje de referen- Obregon y su entorno productivo1 cia y funcionamiento para un muy dinarni- E procurara describir las condiciones co espacio agrfcola del noroeste de Mexico, que hicieron nacer y transformaron a esta de un arnbito que incluye el sur de Sonora urbe -entre los afios veinte y la decada de y el norte de Sinaloa. Para una interpreta- ci6n mas adecuada de este proceso regional habremos de utilizar un par de conceptos * Con la colaboraci6n de Marcela Preciado Nava. ** Profesor-investigador de la Universidad Aut6- muy instrumentales, heredados de la mas noma de Nuevo Le6n. Miembro del Sistema Nacional reciente literatura sobre la Europa del sur: de lnvestigadores (nivel III). Especializado en la his- sistema productivo local.y agrociudad. toria econ6mica y empresarial de! norte de Mexico, ha El texto se concentrara en: a) brindar publicado resultados de investigacion en Alemania, una sucinta referencia sobre ambas nocio- Italia, Holanda, Espana, Portugal, Inglaterra, Suecia, nes; b) ubicar historicarnente y delinear el Escados Unidos, Argentina, Brasil, Colombia, Vene- territorio (o el espacio regional) que ani- zuela, Uruguay y Mexico. Entre sus libros destacan: do el surgimiento de la principal urbe que Propietarios, empresarios y empresa en el norte de Mexico, Si- existe hoy entre Hermosillo y Culiacan; glo XXI, Mexico, 2000; Del mercado protegido al mer c) practicar una resefia de la agricultura cado global. -

PUNTOS RESOLUTIVOS DE LAS SENTENCIAS DICTADAS POR LOS TRIBUNALES AGRARIOS Dictada El 8 De Julio De 1996

Lunes 2 de diciembre de 1996 BOLETIN JUDICIAL AGRARIO 3 PUNTOS RESOLUTIVOS DE LAS SENTENCIAS DICTADAS POR LOS TRIBUNALES AGRARIOS Dictada el 8 de julio de 1996 JUICIO AGRARIO: 449/T.U.A.-28/95 Pob.: “VILLA HIDALGO” Mpio.: Villa Hidalgo Dictada el 8 de julio de 1996 Edo.: Sonora Acc.: Reconocimiento de derechos Pob.: “VILLA HIDALGO” agrarios. Mpio.: Villa Hidalgo Edo.: Sonora PRIMERO. Es improcedente el Acc.: Reconocimiento de derechos reconocimiento de derechos agrarios solicitado agrarios. por JOSÉ DURAZO VELÁZQUEZ, derivado de la aceptación de la Asamblea General de PRIMERO. Es improcedente el Ejidatarios celebrada el catorce de junio de mil reconocimiento de derechos agrarios solicitado novecientos noventa y cuatro, en el Poblado por IGNACIO MORENO LEYVA, derivado "VILLA HIDALGO", Municipio de Villa de la aceptación de la Asamblea General de Hidalgo, Sonora, conforme a lo razonado en el Ejidatarios celebrada el catorce de junio de mil último considerando de esta resolución. novecientos noventa y cuatro, en el Poblado SEGUNDO. Se deja a salvo los derechos "VILLA HIDALGO", Municipio de Villa del C. JOSÉ DURAZO VELÁZQUEZ, para Hidalgo, Sonora, conforme a lo razonado en el que en su oportunidad pueda volver a ejercitar último Considerando de esta resolución. la acción pretendida en el presente asunto. SEGUNDO. Se deja a salvo los derechos TERCERO. Notifíquese personalmente al del C. IGNACIO MORENO LEYVA, para interesado, y publíquense los puntos que en su oportunidad pueda volver a ejercitar resolutivos de esta fallo en el Boletín Judicial la acción pretendida en el presente asunto. Agrario y en los estrados de este Tribunal. En TERCERO. -

Pest-Free Areas

Pest-Free Areas The following table lists countries and associated areas that meet the APHIS requirements for designated pest-free areas in accordance with 7 CFR 319.56- 5. Country Pest(s) Pest-free Area Argentina Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly) Cer- The Patagonia Provinces of Neuguen, Rio Negro, atitis capitata and Anastrepha spp. Chabut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego. This includes fruit flies areas along the valleys of the Rio Colorado and Rio Negro rivers and areas of the southern part of the Men- doza Province, south of the following coordinates: lat 33o 13’ 40.98” S, length 69o 54’ 36.86” W; lat 33o 13’ 40.98” S, length 69o 04’ 18.24” W; lat 33o 29’ 29” S, length 68o 59’ 20” W; lat 34o 02’ 47” S, length 67o 57’ 17” W; lat 34o 02’ 47” S, length 66o 44’ 06.05” W Australia Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly) (Cer- The Riverland district of South Australia, defined as the atitis capitata), the Queensland fruit county of Hamley; the geographical subdivisions, called fly (Bactrocera tryoni or QFF) and hundreds, of Bookpurnong, Cadell, Eba, Fisher, Forster, other fruit flies destructive of citrus Gordon, Hay, Holder, Katarapko, Loveday, Markaranka, Morook, Murbko, Murtho, Nildottie, Paisley, Parcoola, Paringa, Pooginook, Pyap, Ridley, Skurray, Stuart, and Waikerie; and the Parish of Onley of the Shire of Mildura, Victoria Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly) (Cer- Tasmania atitis capitata) and the Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni) Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly) (Cer- Eastern Australia, defined as the Northern Territory, atitis capitata) -

Flycatcher 0305-06.P65

May-June 2003 Vermilionlycatcher Tucson Audubon Society F www.tucsonaudubon.org Leaders in Conservation & Education since 1949 Volume 47, Number 8 ISSN 1094-9909 Tucson Audubon Societys FOURTH ANNUAL Spring Appeal Don’t forget to open your spring appeal letter. Let spring migration inspire you to send The ironwood symbolizes the richness The Festival will open at 3:00 p.m. with a in a donation soon. of the Sonoran Desert. It is our finest tree— blessing by the Tohono O’odham Nation’s re- durable, timeless, and nurturing. There is spected elder, Daniel Preston, and will continue no better way to learn about its beauty and into the evening with a variety of activities and its vital role in nature than to attend the entertainment for all ages amidst the bloom- Inside Ironwood Festival hosted by Tucson Au- ing ironwoods and towering saguaros of the na- dubon Society. ture preserve. Included – David Yetman, host of among the activities cel- the public television show ebrating the regional beauty, Calendar .................. 10 The Desert Speaks. diversity, and cultural rich- Tucson Audubon News 4 ness of the Sonoran Desert Dastardly Duos ........ 20 Join us on Saturday, May are live animal presenta- Field Trips .................. 6 3 as the Tucson Audubon So- tions, nature walks, Field Trip Reports ...... 8 ciety hosts the 4th annual Iron- storytelling, cultural perfor- Mason Audubon Center wood Festival with a rich pro- mances, tree planting, News ...................... 12 gram of activities and enter- hands-on booth activities, Meeting program ...... 28 tainment. More than 500 regional food and beverages, Membership people are expected to attend and musical entertainment. -

A GEOGRAPHIC STUDY of the TOURIST INDUSTRY of MEXICO by 1957. MASTER of SCIENCE

A GEOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE TOURIST INDUSTRY OF MEXICO By WILLIAM Mo BRYAN ';}".~ Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater i, Oklahoma 1957. Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 1957 ? .• OKlAHOMk\ STATE UN1VER,SFt•·..t " lf8RARY " OCT 1 1957 A GEOGRAPHIC ·STUDY OF ' THE TOURIST INDUSTRY OF MEXICO Thesis Approved: > Dean of the Graduate School 385416 ii PREFACE American citizens do not visualize tourism as a complete industryo They think of the hotel., restaurant 9 souvenir.I) transportation9 garage and filling stations 9 and sporting goods businesses as individual enterprises rather than one large combined industryo Our demooracy 9 high economic standards 9 and liberal wa:y of life allow the American a:i tizen much time to spend in travel. An over~all look at tourism in one country 9 Mexico.I) has shown me that a large number of enterprisers are interested in this industryll and that country's government goes to great lengths to promote and build up a good tourist trade. While in the United States Navy, I first noticed the great impact of tourism in foreign lands., especially Hawaiio I became interested in Mexico while working in San Antonio., Texaso While there., several trips were made to border towns., and the large tourist trade between the United States and Mexico was realizedo A background in geography has given me a deeper knowledge of Mexi~oj and a reconn.aissanoe trip to that country provided the incentive to make this study. -

Iota Directory of Islands Regional List British Isles

IOTA DIRECTORY OF ISLANDS sheet 1 IOTA DIRECTORY – QSL COLLECTION Last Update: 22 February 2009 DISCLAIMER: The IOTA list is copyrighted to the Radio Society of Great Britain. To allow us to maintain an up-to-date QSL reference file and to fill gaps in that file the Society's IOTA Committee, a Sponsor Member of QSL COLLECTION, has kindly allowed us to show the list of qualifying islands for each IOTA group on our web-site. To discourage unauthorized use an essential part of the listing, namely the geographical coordinates, has been omitted and some minor but significant alterations have also been made to the list. No part of this list may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. A shortened version of the IOTA list is available on the IOTA web-site at http://www.rsgbiota.org - there are no restrictions on its use. Islands documented with QSLs in our IOTA Collection are highlighted in bold letters. Cards from all other Islands are wanted. Sometimes call letters indicate which operators/operations are filed. All other QSLs of these operations are needed. EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN # ENGLAND / SCOTLAND / WALES B EU-005 G, GM, a. GREAT BRITAIN (includeing England, Brownsea, Canvey, Carna, Foulness, Hayling, Mersea, Mullion, Sheppey, Walney; in GW, M, Scotland, Burnt Isls, Davaar, Ewe, Luing, Martin, Neave, Ristol, Seil; and in Wales, Anglesey; in each case include other islands not MM, MW qualifying for groups listed below): Cramond, Easdale, Litte Ross, ENGLAND B EU-120 G, M a.