A Critical Friendship Elizabeth Murphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

22. the Immortal Bhaktas

22. The Immortal Bhaktas AMONG all forms of Sadhana, Bhakti (devotion to the Lord) is the easiest and holiest. Bhakti is derived from the root "Bhaj", with the suffix "thi." It means Seva (Service). It denotes a feeling of friendship coupled with awe. For one who is a creature of the gunas (Satwa, Rajas, Tamas), to understand what transcends the gunas, an attitude of humility and reverence is required. "Bhaja Sevaayaam" (worship the Divine through Seva). Bhakti calls for utilising the mind, speech and body to worship the Lord. It represents total love. Devotion and love are inseparable and interdependent. Bhakti is the means to salvation. Love is the expression of Bhakti. Narada declared that worshipping the Lord with boundless love is Bhakti. Vyasa held that performing worship with love and adoration is Bhakti. Garga Rishi declared that serving the Lord with purity of mind, speech and body is Bhakti. Yajnavalkya held that true Bhakti consists in controlling the mind, turning it inwards and enjoying the bliss of communion with the Divine. Another view of Bhakti is concentration of the mind on God and experiencing oneness with the Divine. Win love through love Although many sages have expressed different views about the nature of Bhakti, the basic characteristic of devotion is Love. Love is present in every human being in however small a measure. The riva (individual) is an aspect of the Divine, who is the supreme embodiment of Love. Man also is an embodiment of Love, but because his love is directed towards worldly objects, it gets tainted and he is unable to get a vision of God in all His beauty. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Letters Mingle Soules

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 8 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Spring 1987 Article 2 5-15-1987 Letters Mingle Soules Ben Howard Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Recommended Citation Howard, Ben (1987) "Letters Mingle Soules," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howard: Letters Mingle Soules Letters Mingle Soules Si1; mure than kisses) letters mingle Soules; Fm; thus friends absent speake. -Donne, "To Sir Henry Wotton" BEN HOWARD EW LITERARY FORMS are more inviting than the familiar IF letter. And few can claim a more enduring appeal than that imi tation of personal correspondence, the letter in verse. Over the centu ries, whether its author has been Horace or Ovid, Dryden or Pope, Auden or Richard Howard, the verse letter has offered a rare mixture of dignity and familiarity, uniting graceful talk with intimate revela tion. The arresting immediacy of the classic verse epistles-Pope's to Arbuthnot, Jonson's to Sackville, Donne's to Watton-derives in part from their authors' distinctive voices. But it is also a quality intrinsic to the genre. More than other modes, the verse letter can readily com bine the polished phrase and the improvised excursus, the studied speech and the wayward meditation. The richness of the epistolary tradition has not been lost on con temporary poets. -

Lovesickness” in Late Chos Ǒn Literature

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reinterpreting “Lovesickness” in Late Chos ǒn Literature A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Janet Yoon-sun Lee 2014 © Copyright by Janet Yoon-sun Lee 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reinterpreting “Lovesickness” in Late Chos ǒn Literature By Janet Yoon-sun Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Peter H. Lee, Chair My dissertation concerns the development of the literary motif of “lovesickness” (sangsa py ǒng ) in late Chos ǒn narratives. More specifically, it examines the correlation between the expression of feelings and the corporeal symptoms of lovesickness as represented in Chos ǒn romance narratives and medical texts, respectively, of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As the convergence of literary and medical discourse, lovesickness serves as a site to define both the psychological and physical experiences of love, implying the correlation between mind and body in the non-Western tradition. The analysis itself is re-categorized into the discussions of the feeling and the body. In the discussion of the feeling, it will be argued that the feeling of longing not only occupies an important position in literature, but also is gendered and structured in lyrics and narratives of the seventeenth century. In addressing the rubric of feelings of “longing,” this part seeks the ii theoretical grounds of how the intense experience of longing is converted to language of love and to bodily symptoms to constitute the knowledge of lovesickness. The second part concerns the representation of lovesick characters in Korean romance, particularly concerning the body politics of the Chos ŏn society. -

Aristotle on Love and Friendship

ARISTOTLE ON LOVE AND FRIENDSHIP DAVID KONSTAN Philia is exceptional among ancient Greek value terms for the number of still unre- solved, or at least intensely debated, questions that go to the heart of its very nature.1 Does it mean “friendship”, as it is most commonly rendered in discussions of Aris- totle, or rather “love”, as seems more appropriate in some contexts? Whether it is love, friendship, or something else, is it an emotion, a virtue, or a disposition? The same penumbra of ambiguity surrounds the related term philos, often rendered as “friend” but held by some to include kin and other relations, and even to refer chiefly to them. Thus, Elizabeth Belfiore affirms that “the noun philos surely has the same range as philia, and both refer primarily, if not exclusively, to relationships among close blood kin” (2000: 20). In respect to the affective character of philia, Michael Peachin (2001: 135 n. 2) describes “the standard modern view of Roman friendship” as one “that tends to reduce significantly the emotional aspect of the relationship among the Ro- mans, and to make of it a rather pragmatic business”, and he holds the same to be true of Greek friendship or philia. Scholars at the other extreme maintain that ancient friendship was based essentially on affection. As Peachin remarks (ibid., p. 7), “D. Konstan [1997] has recently argued against the majority opinion and has tried to inject more (modern-style?) emotion into ancient amicitia”. Some critics, in turn, have sought a compromise between the two positions, according to which ancient friend- ship involved both an affective component and the expectation of practical services. -

Singing Accent Americanisation in the Light of Frequency Effects: Lot Unrounding and Price Monophthongisation in Focus

Research in Language, 2018, vol. 16:2 DOI: 10.2478/rela-2018-0008 SINGING ACCENT AMERICANISATION IN THE LIGHT OF FREQUENCY EFFECTS: LOT UNROUNDING AND PRICE MONOPHTHONGISATION IN FOCUS MONIKA KONERT-PANEK University of Warsaw [email protected] Abstract The paper investigates – within the framework of usage-based phonology – the significance of lexical frequency effects in singing accent Americanisation. The accent of Joe Elliott of a British band, Def Leppard is analysed with regard to LOT unrounding and PRICE monophthongisation. Both auditory and acoustic methods are employed; PRAAT is used to provide acoustic verification of the auditory analysis whenever isolated vocal tracks are available. The statistical significance of the obtained results is verified by means of a chi- square test. In both analysed cases the percentage of frequent words undergoing the change is higher compared with infrequent ones and in the case of PRICE monphthongisation the result is statistically significant, which suggests that word frequency may affect singing style variation. Keywords: frequency effects, LOT unrounding, popular music, PRICE monophthong- gisation, singing accent, usage-based phonology 1. Introduction The phenomenon of style-shifting involved in pop singing in general and the Americanisation of British singing accent in particular have been investigated from various theoretical perspectives (Trudgill 1983, Simpson 1999, Beal 2009, Gibson and Bell 2012 among others). Depending on the theoretical standpoint, the notions of identity, reference style or default accent have been brought to light and assigned major explanatory power. Trudgill (1983) in his seminal paper on the sociolinguistics of British pop-song pronunciation interprets the emulation of the American accent as a symbolic tribute to the origins of popular music and provides the list of six characteristic features of this stylisation (1), two of which ((1c) and (1d)) are addressed in the present paper. -

Live, Laugh, Limerence

Live, Laugh, Limerence An Opera Buffa in four acts Libretto by Marijke De Roover 2019 De Roover’s introductory notes: The performance needs the naturalism of the text. All characters exist all at once all as one. The landscape in which the experience is set could be a metropolitan studio apartment, an AA meeting, a deep dream or a dead star (more chance of it being a karaoke booth tbh). The I in the text is collective, the time suggestive. The simultaneity of the four parts of the text can be portrayed any which way. Me to me: You have a responsibility towards your audience. Please keep all the ducks in a row! The ducks: 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS When reading this story out loud, please use the following voices: ELETTRA: fast-paced, sweet, melodic. LOTTE (V.O.): distant but sensitive, straight forward. TURANDOT (V.O.): wild but judgemental (but their friendship is like this). → darlin’, this kind of love is not viable (I can just see it with this fat american country accent lol) Or (Marilyn is so sweet and Jane is much more rough/tough) NARRATOR (V.O.): voice of god (distant), ironic, calm . 2 SCENES PROLOGUE: IN WHICH THE NARRATOR EXPRESSES HER DOUBTS ACT ONE: THE DAY I STOPPED DRINKING I BECAME A PLAYWRIGHT THAT JUST SITS IN COFFEE BARS Which introduces us to the tragedy and its Scene 1: protagonist A brief encounter Scene 2: I took a deep breath and listened to the old bray Scene 3: of my heart. I am. I am. I am A realistic portrayal of someone using love as an Scene 4: escapist drug ACT TWO: A KISS. -

Laurence Donovan Papers (ASM0124)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Laurence Donovan papers (ASM0124) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0124 Laurence Donovan papers Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 8 id7855, Correspondence, 1945-2001 ........................................................................................................... -

Donald Justice - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Donald Justice - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Donald Justice(12 August 1925 - 6 August 2004) Donald Justice was an American poet and teacher of writing. <b>Life and Career</b> Justice grew up in Florida, and earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Miami in 1945. He received an M.A. from the University of North Carolina in 1947, studied for a time at Stanford University, and ultimately earned a doctorate from the University of Iowa in 1954. He went on to teach for many years at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, the nation's first graduate program in creative writing. He also taught at Syracuse University, the University of California at Irvine, Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Florida in Gainesville. Justice published thirteen collections of his poetry. The first collection, The Summer Anniversaries, was the winner of the Lamont Poetry Prize given by the Academy of American Poets in 1961; Selected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1980. He was awarded the Bollingen Prize in Poetry in 1991, and the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry in 1996. His honors also included grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1997 to 2003. His Collected Poems was nominated for the National Book Award in 2004. Justice was also a National Book Award Finalist in 1961, 1974, and 1995. -

Roots & Rituals

ROOTS & RITUALS The construction of ethnic identities Ton Dekker John Helsloot Carla Wijers editors Het Spinhuis Amsterdam 2000 Selected papers of the 6TH SIEF conference on 'Roots & rituals', Amsterdam 20-25 April 1998 This publication was made possible by the Ministery of the Flemish Community, Division of the non-formal adult education and public libraries, in Bruxelles ISBN 90 5589 185 1 © 2000, Amsterdam, the editors No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright owners. Cover design: Jos Hendrix Lay-out: Ineke Meijer Printed and bound in the Netherlands Het Spinhuis Publishers, Oudezijds Achterburgwal 185, 1012 DK Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ix Ton Dekker, John Helsloot & Carla Wijers SECTION I Ethnicity and ethnology Wem nützt 'Ethnizität'? 3 Elisabeth & Olaf Bockhorn Ethnologie polonaise et les disciplines voisines par rapport à l'identification nationale des Polonais 11 Wojciech Olszewski Üne ethnie ingérable: les Corses 25 Max Caisson SECTION II Ethnie groups, minorities, regional identities Ethnic revitalization and politics of identity among Finnish and Kven minorities in northern Norway 37 Marjut Anttonen Division culturelle du travail et construction identitaire dans le Pinde septentrional 53 Evangelos Karamanes Managing locality among the Cieszyn Silesians in Poland 67 Marian Kempny Musulmanisches Leben im andalusischen Granada -

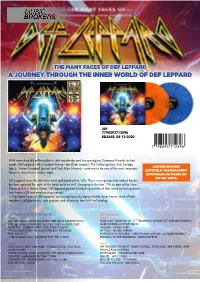

A Journey Through the Inner World of Def Leppard

THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD A JOURNEY THROUGH THE INNER WORLD OF DEF LEPPARD 2LP 7798093712896 RELEASE: 04-12-2020 With more than 65 million albums sold worldwide and two prestigious Diamond Awards to their credit, Def Leppard with its current line-up –Joe Elliott (vocals), Phil Collen (guitar), Rick Savage LIMITED EDITION (bass), Vivian Campbell (guitar) and Rick Allen (drums)— continue to be one of the most important GATEFOLD TRANSPARENT forces in rock music.n many ways, ORANGE/BLUE MARBLED 180 GR. VINYL Def Leppard were the definitive hard rock band of the ‘80s. There were groups that rocked harder, but few captured the spirit of the times quite as well. Emerging in the late ‘70s as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Def Leppard gained a following outside of that scene by toning down their heavy riffs and emphasizing melody. In The Many Faces of Def Leppard, we are going to dig deep into the lesser known work of their members, collaborations, side projects and of course, their hit-filled catalog. LP1 - THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD LP2 - THE SONGS Side A Side A ALL JOIN HANDS - ROADHOUSE FEAT. PETE WILLIS & FRANK NOON POUR SOME SUGAR ON ME - LEE THOMPSON, JOHNNY DEE, RICHARD KENDRICK, I WILL BE THERE - GOMAGOG FEAT. PETE WILLIS & JANICK GERS MARKO PUKKILA & HOWIE SIMON DOIN’ FINE - CARMINE APPICE FEAT. VIVIAN CAMPBELL HYSTERIA - DANIEL FLORES ON A LONELY ROAD - THE FROG & THE RICK VITO BAND LET IT GO - WICKED GARDEN FEAT. JOE ELLIOTT ROCK ROCK TIL YOU DROP - CHRIS POLAND, JOE VIERS & RICHARD KENDRICK OVER MY DEAD BODY - MAN RAZE FEAT.