The Industrialization of Animal Agriculture in the Developing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

OTTAWA HUMANE SOCIETY 2019•20 ANNUAL REPORT YOU give so many homeless and injured animals a second chance at a better life. Thank you for rescuing, reuniting and rehoming Ottawa’s most vulnerable animals. Mission: To lead Ottawa in building a humane and compassionate community for all animals. By the Numbers: You Save Lives Veterinarians performed 2,804 surgeries on animals in the care of the Ottawa Humane Society last year. They completed: Spays and Dental Diagnostic 2,804 neuters procedures X-rays procedures Surgeries 2,622 541 761 210 In the Nick of Time Last November, Elsie, a After the surgery, Elsie was beautiful chocolate lab, wrapped in a warm blanket was rushed to the OHS. and left to gently wake up in She was dehydrated and critical care. The surgery may malnourished from refusing have been a success, but there to eat for two weeks. were still many steps on her She was suffering from road to recovery. She needed the advanced stages of medications, dental care and pyometra — an infection of tests to check for side effects the uterus that is fatal if left from the surgery. untreated. Elsie’s condition was critical but thanks to Thanks to you, Elsie’s story you, she was given hope. has a happy ending. Once she was fully healed, the There was little time. OHS OHS made her available for veterinarians had to act fast. adoption and she soon went Elsie’s entire uterus had to be removed along with home with her forever family. From the surgery, to the all the pus built up from the infection. -

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020 AUTHORED BY: Jeff Moyer, Andrew Smith, PhD, Yichao Rui, PhD, Jennifer Hayden, PhD REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE IS A WIN-WIN-WIN CLIMATE SOLUTION that is ready for widescale implementation now. WHAT ARE WE WAITING FOR? Table of Contents 3 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 A Potent Corrective 11 Regenerative Principles for Soil Health and Carbon Sequestration 13 Biodiversity Below Ground 17 Biodiversity Above Ground 25 Locking Carbon Underground 26 The Question of Yields 28 Taking Action ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 30 Soil Health for a Livable Future Many thanks to the Paloma Blanca Foundation and Tom and Terry Newmark, owners of Finca Luna Nueva Lodge and regenerative farm in 31 References Costa Rica, for providing funding for this paper. Tom is also the co-founder and chairman of The Carbon Underground. Thank you to Roland Bunch, Francesca Cotrufo, PhD, David Johnson, PhD, Chellie Pingree, and Richard Teague, PhD for providing interviews to help inform the paper. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The environmental impacts of agricultural practices This introduction is co-authored by representatives of two The way we manage agricultural land 140 billion new tons of CO2 contamination to the blanket of and translocation of carbon from terrestrial pools to formative organizations in the regenerative movement. matters. It matters to people, it matters to greenhouse gases already overheating our planet. There is atmospheric pools can be seen and felt across a broad This white paper reflects the Rodale Institute’s unique our society, and it matters to the climate. no quarreling with this simple but deadly math: the data are unassailable. -

Program Guide For: Newly Adopted Course of Study Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources Cluster, and Argiscience Middle School

2020-2021 PROGRAM GUIDE FOR: NEWLY ADOPTED COURSE OF STUDY AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND NATURAL RESOURCES CLUSTER, AND ARGISCIENCE MIDDLE SCHOOL NOVEMBER 20, 2020 ALABAMA STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION CAREER AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION ANDY CHAMNESS, EDUCATION ADMINISTRATOR COLLIN ADCOCK, EDUCATION SPECIALIST JERAD DYESS, EDUCATION SPECIALIST MAGGIN EDWARDS, ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT (334) 694-4746 Revised 2/23/2021 Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources Cluster This cluster prepares students for employment in career pathways that relate to the $70 billion plus industry of agriculture. The mission of agriscience education is to prepare students for successful careers and a lifetime of informed choices in the global agriculture, food, fiber and natural resource industries. There are six program areas in this cluster: General Agriculture, Animal Science, Plant Science, Environmental and Natural Resources, Industrial Agriculture and Middle School. Extended learning experiences to enrich and enhance instruction are reinforced through learner participation in the career and technical student organization related to agriculture education. The National FFA organization (FFA) serves as the CTSO for this cluster. Additionally, project-based learning experiences, otherwise known as a Supervised Agriculture Experience (SAE) are an integral part of agriculture education. General Agriculture Program Pathway Career (Must teach three courses from this program list within two years) Pathway This program is designed to deliver a variety of agricultural disciplines -

Handout 3.1: Looking at Industrial Agriculture and Agricultural Innovation

Handout 3.1: Looking at Industrial Agriculture and Agricultural Innovation Agricultural Innovation:1 “A form of modern farming that refers to the industrialized production of livestock, poultry, fish and crops. The methods it employs include innovation in agricultural machinery and farming methods, genetic technology, techniques for achieving economies of scale in production, the creation of new markets for consumption, the application of patent protection to genetic information, and global trade.” Benefits Downsides + Cheap and plentiful food ‐ Environmental and social costs + Consumer convenience ‐ Damage to fisheries + Contribution to the economy on many levels, ‐ Animal waste causing surface and groundwater from growers to harvesters to sellers pollution ‐ Increased health risks from pesticides ‐ Heavy use of fossil fuels leading to increased ozone pollution and global warming Factors that influence agricultural innovation • Incentive or regulatory government policies • Different abilities and potentials in agriculture and food sectors • Macro economic conditions (i.e. quantity and quality of public and private infrastructure and services, human capital, and the existing industrial mix) • The knowledge economy (access to agricultural knowledge and expertise) • Regulations at the production and institution levels The Challenge: Current industrial agriculture practices are temporarily increasing the Earth’s carrying capacity of humans while slowly destroying its long‐term carrying capacity. There is, therefore, a need to shift to more sustainable forms of industrial agriculture, which maximize its benefits while minimizing the downsides. Innovation in food Example (Real or hypothetical) processing Cost reduction / productivity improvement Quality enhancement / sensory performance Consumer convenience / new varieties Nutritional delivery / “healthier” Food safety 1 www.wikipedia.org . -

Brock Watt Sandra 2006.Pdf (2.336Mb)

Utilitarianism and Buddhist Ethics: A Comparative Approach to the Ethics of Animal Research Sandra F. Watt, B.A. Department of Philosophy Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master alArts Faculty of Humanities, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © July, 2006 cMMEs AGIBSON LIBRARY BlOCK UNIVERSITY 8f.OO'HAIUNES ON Abstract This thesis explores the comparison utilitarianism and Buddhist ethics as they can be applied to animal research. It begins by examining some of the general discussions surrounding the use of animals in research. The historical views on the moral status of animals, the debate surrounding their use in animals, as well as the current 3R paradigm and its application in Canadian research are explored. The thesis then moves on to expound the moral system of utilitarianism as put forth by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, as well as contemporary additions to the system. It also looks at the basics of Buddhist ethics well distinguishing the Mahayana from the Therevada. Three case studies in animal research are used to explore how both systems can be applied to animal research. It then offers a comparison as to how both ethical systems function within the field of animal research and explores the implications in their application on its practice. Table of Contents Introduction pg 1 Chapter One pg 7 1.1 The Moral Status of Animals pg 8 1.2 The Debate Surrounding Animal Research pg 17 1.3 The Benefits of Animal Research pg 21 1.4 The Current Paradigm: The Three Rs pg23 1.5 Current Canadian -

50 Things You May Not Know About the Ottawa Humane Society 1

50 Things You May Not Know about the Ottawa Humane Society 1. The Ottawa Humane Society is a very old organization. The OHS was founded in 1888, as the Women's Humane Society. Last year was our 125th Anniversary. 2. We are the parent of the Children's Aid Society. The OHS was founded to protect the welfare of animals and children. The Children's Aid Society branched off from the OHS several years later. 3. The Ottawa Humane Society is a not-for-profit and a registered charity. We are governed by a board of 14. 4. The OHS may be bigger than you think. Last year, our regular staff compliment was 102 full- and part-time staff. (Though almost half are part-time.) Our budget is $6.2 million. Nearly two-thirds of this comes from donors and supporters. 5. The OHS is now located at 245 West Hunt Club Many people still don't know that we relocated in June 2011. 6. West Hunt Club is the OHS's fourth shelter. The first was built on Mann Avenue in 1933. 7. The new OHS West Hunt Club shelter is more than three times the size of the old Champagne Ave. Shelter. Despite its size, one month after it opened in June 2011, the new shelter was full. 8. The OHS cares for over 10,000 animals every year. Last year, 6,181 were cats; 2,111 were dogs; 1,279 were wildlife; 411 were small animals 9. Despite the fact that Ottawa is growing, the number of homeless animals is not. -

2019 Biennial Compensation and Benefits Survey EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Information Submitted on Or Before May 7, 2020

2019 Biennial Compensation and Benefits Survey EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Information Submitted on or before May 7, 2020 I N T R O D U C T I O N A N D I N S I G H T S Organizations in the field of animal welfare employ a unique workforce with distinctive expertise in leadership, organizational governance, animal protection, animal cruelty investigation, behavior rehabilitation, veterinary care, adoption, fundraising, advocacy, human resources, finance, community education and collaboration. Although compensation and benefits surveys exist for many industries, no salary study is compatible with the knowledge and skills needed for mastery of animal welfare. For that reason, The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement (The Association) leadership were compelled to begin collecting data in 2003 (based on FY 2002 data). Since 2003, animal welfare services have evolved: adoption is no longer the main activity at animal care facilities as the numbers of homeless dogs and cats have declined in many regions; community needs have altered; collaborations and mergers have increased; and, animal focused legislation has fluctuated. In response, animal care facilities models continue to adapt to community and animal needs. Consequently The Association volunteer leadership continually reviews the compensation and benefits survey adding or altering job descriptions and accessing needs for additional decision making data. For instance, the effect on salary of those achieving Certified Animal Welfare Administrator (CAWA) status; or, being a male/female in the same role are now studied. In 2019 the first “digital” survey was launched, based on FY 2018 data, allowing participants to instantly compare their data with other regions and budget size over a variety of key performance indicators. -

Industrial Agriculture, Livestock Farming and Climate Change

Industrial Agriculture, Livestock Farming and Climate Change Global Social, Cultural, Ecological, and Ethical Impacts of an Unsustainable Industry Prepared by Brighter Green and the Global Forest Coalition (GFC) with inputs from Biofuelwatch Photo: Brighter Green 1. Modern Livestock Production: Factory Farming and Climate Change For many, the image of a farmer tending his or her crops and cattle, with a backdrop of rolling fields and a weathered but sturdy barn in the distance, is still what comes to mind when considering a question that is not asked nearly as often as it should be: Where does our food come from? However, this picture can no longer be relied upon to depict the modern, industrial food system, which has already dominated food production in the Global North, and is expanding in the Global South as well. Due to the corporate take-over of food production, the small farmer running a family farm is rapidly giving way to the large-scale, factory farm model. This is particularly prevalent in the livestock industry, where thousands, sometimes millions, of animals are raised in inhumane, unsanitary conditions. These operations, along with the resources needed to grow the grain and oil meals (principally soybeans and 1 corn) to feed these animals place intense pressure on the environment. This is affecting some of the world’s most vulnerable ecosystems and human communities. The burdens created by the spread of industrialized animal agriculture are wide and varied—crossing ecological, social, and ethical spheres. These are compounded by a lack of public awareness and policy makers’ resistance to seek sustainable solutions, particularly given the influence of the global corporations that are steadily exerting greater control over the world’s food systems and what ends up on people’s plates. -

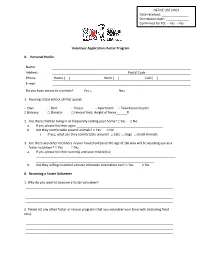

Volunteer Application: Foster Program A. Personal Profile Name

OFFICE USE ONLY Date received: _______________ Orientation date: _____________ Confirmed for FO: □ Yes □ No Volunteer Application: Foster Program A. Personal Profile Name: Address: Postal Code Phone: Home ( ) Work ( ) Cell ( ) E-mail: Do you have access to a vehicle? Yes □ No□ 1. Housing status (check all that apply): □ Own □ Rent □ House □ Apartment □ Townhouse/duplex □ Balcony □ Elevator □ Fenced Yard; Height of fence______ft 2. Are there children living in or frequently visiting your home? □ Yes □ No a. If yes, please list their ages: ________________________________________________ b. Are they comfortable around animals? □ Yes □ No i. If yes, what are they comfortable around? □ Cats □ Dogs □ Small Animals 3. Are there any other members in your household (over the age of 18) who will be assisting you as a foster volunteer? □ Yes □ No a. If yes, please list their name(s) and your relation(s): ______________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ b. Are they willing to attend a foster volunteer orientation too? □ Yes □ No B. Becoming a Foster Volunteer 1. Why do you want to become a foster volunteer? 2. Please list any other foster or rescue programs that you volunteer your time with (including feral cats): 3. Please provide a brief description of your experience with very young, ill, injured, or under socialized animals: 5. Please indicate the amount of time per day that you have to dedicate to your foster animal(s): 6. How many hours will your foster animal(s) be alone on a regular basis? 7. We ask foster volunteers to make a commitment of one year to the foster program. Is there anything in the next year that will prevent you from maintaining this commitment (for example: traveling down south for the winter)? 8. -

Opting out of Industrial Meat

OPTING OUT OF INDUSTRIAL MEAT HOW TO STAND AGAINST CRUELTY, SECRECY, AND CHEMICAL DEPENDENCY IN FOOD ANIMAL PRODUCTION JULY 2018 www.centerforfoodsafety.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: CRUELTY, SECRECY, & CHEMICAL DEPENDENCY 1 II. WHAT IS “INDUSTRIAL MEAT”? 7 III. TEN REASONS TO OUT OPT OF INDUSTRIAL MEAT 11 For Our Health 11 For Food Workers 13 For Pollinators 14 For Water Conservation 15 For Animals 17 For Climate 18 For Healthy Communities 19 For Food Safety 19 For Farmers 21 For Local Economies 22 IV. HOW TO OPT OUT OF INDUSTRIAL MEAT 23 1. Eat Less Meat Less Often 24 2. Choose Organic, Humane, and Pasture-Based Meat Products 26 3. Eat More Organic and Non-GMO Plant Proteins 28 V. CONCLUSION & POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS CHARTS Plant-Based Sources of Protein 30 Fish 31 ENDNOTES 32 CENTER FOR FOOD SAFETY OPTING OUT OF INDUSTRIAL MEAT INTRODUCTION: CRUELTY, SECRECY, & CHEMICAL DEPENDENCY hat came first—the chicken or the egg? ible toll on our climate, water, soils, wildlife, and WIt’s difficult to know whether increasing health. What’s more, massive production of animals consumer demand for meat and poultry in these conditions requires intensive production products has driven drastic increases in production of grains for feed, which contributes to high pes - levels, or vice versa. What we do know with cer - ticide use and threatens wildlife. 1 tainty, though, is that demand for and production of meat and poultry products has increased dra - Nevertheless, demand for meat and poultry con - matically in the U.S. and globally in the last 70 years. -

Pack (Team) Challenge Kit

Pack (team) Challenge Kit Wiggle Waggle Walkathon & Run for the Animals Sunday, September 13th, 2015 - Queen Juliana Park, Dow’s Lake Participating in the Pack (team) Challenge at the Ottawa Humane Society’s Wiggle Waggle Walkathon and/or Run for the Animals is fun and easy! This Pack kit gives you all the information you need to register, enter a Pack, and raise pledges for the walkathon and/or run. Please contact us at 613-725-3166 x 238 or at [email protected] with any questions or concerns. ottawahumane.ca/walk ottawahumane.ca/run Pack Challenge 2015 Rules and Guidelines What is a Pack? A Pack is a group of at least four registered individuals, including but not limited to corporations (profit, non- profit, government), the general public, sports teams and community groups. How to Participate in the Pack Challenge: Every Pack must have a Pack Captain, who motivates, informs their team about the walkathon/run, and acts as a liaison between the team and the OHS. The Pack Captain’s responsibilities include: 1. ONLINE REGISTRATION a. Register their Pack online, and encourage all Pack members to register and solicit online (www.ottawahumane.ca/walk or www.ottawahumane.ca/run.) b. Come to kit pick up/pre-registration on Thursday, Sept 10 from 5 – 8 p.m. at the OHS OR Saturday Sept 12 from 12-4 p.m. at Queen Juliana Park, Dow’s Lake to register and collect incentive prizes (if applicable) to distribute to Pack members. OR 2. OFFLINE REGISTRATION a. The Pack Captain notifies the Ottawa Humane Society that they are entering a Pack into the walkathon/run by completing the Pack Information Sheet (attached) and submitting it via email to [email protected] or by fax to 613-725-5674 or in person at 245 West Hunt Club Rd, Ottawa, ON, K2E 1A6. -

Download Standard

The Vol 2 No 2 2019 Ecological ISSN 2515-1967 A peer-reviewed journal Citizen www.ecologicalcitizen.net CONFRONTING HUMAN SUPREMACY IN DEFENCE OF THE EARTH IN THIS ISSUE Saving wild rivers The ‘why’ and ‘how’ Pages 131 and 173 The case against ‘enlightened inaction’ Applying lessons from Henry David Thoreau Page 163 AN INDEPENDENT JOURNAL No article access fees | No publication charges | No financial affiliations About the Journal www.ecologicalcitizen.net The An ecocentric, peer-reviewed, Ecological free-to-access journal EC Citizen ISSN 2515-1967 Cover photo Aims Copyright A protest against damming of 1 Advancing ecological knowledge The copyright of the content belongs to the Vjosa on the river’s banks 2 Championing Earth-centred action the authors, artists and photographers, near Qeserat, Albania. 3 Inspiring ecocentric citizenship unless otherwise stated. However, there is Oblak Aljaz 4 Promoting ecocentrism in political debates no limit on printing or distribution of PDFs 5 Nurturing an ecocentric lexicon downloaded from the website. Content alerts Translations Sign up for alerts at: We invite individuals wishing to translate www.ecologicalcitizen.net/#signup pieces into other languages, helping enable the Journal to reach a wider audience, to contact Social media us at: www.ecologicalcitizen.net/contact.html. Follow the Journal on Twitter: www.twitter.com/EcolCitizen A note on terminology Like the Journal on Facebook: Because of the extent to which some non- www.facebook.com/TheEcologicalCitizen ecocentric terms are embedded in the English language, it is sometimes necessary Editorial opinions for a sentence to deviate from a perfectly Opinions expressed in the Journal do not ecocentric grounding.