AGENDA ITEM 5 & 6 APPENDIX 3 2016/0195/DET and 2016/0196/LBC CONSERVATION STATEMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Pipe Band Championships » Pg 14

the www.scottishbanner.com Scottishthethethe North American EditionBanner 37 Years StrongScottish - 1976-2013 BannerA’ Bhratach Albannach ScottishVolumeScottish 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international BannerBanner Scottish newspaper May 2013 40 Years Strong - 1976-2016 www.scottishbanner.com Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international ScottishA’ Bhratach newspaper May 2013 Albannach VolumeVolumeVolume 40 36 36 Number Number Number 3 11 The 11 The world’sThe world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper September May May 2013 2013 2016 The 2016 World Pipe Band Championships » Pg 14 Celts Exploring Celtic culture » Pg 26 Andy Australia $3.75; North American $3.00; N.Z. $3.95; U.K. £2.00 An Orkney tragedy-100 years on .. » Pg 7 Scotland in Budapest ...................... » Pg 10 Scott The first modern pilgrimage Scotland’s man of steel to Whithorn ........................................ » Pg 25 An artist’s journey round the Moray Coast ............................... » Pg 27 » Pg 12 The ScoTTiSh Banner By: Valerie Cairney Scottishthe Volume Banner 40 - Number 3 The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Editor & Publisher Valerie Cairney A Royal love affair with Scotland Australian Editor Sean Cairney Britain’s Royal Family have long had a love affair with Scotland. Scotland has played a role in EDItorIAL StaFF royal holidays, education, marriages and more. This month the Braemar Gathering will again Jim Stoddart Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot take place highlighting the Royal Family’s special bond with Scotland. From spectacular castle’s, The National Piping Centre David McVey events and history Scotland continues to play its role in shaping one of the world’s most famous families. -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

Parkhill Cottage Lumphanan Banchory AB31 4RP Parkhill Cottage Lumphanan Banchory AB31 4RP

Parkhill Cottage Lumphanan Banchory AB31 4RP Parkhill Cottage Lumphanan Banchory AB31 4RP This four bedroom, detached home enjoys an idyllic rural location on the outskirts of the picturesque village of Lumphanan and close to the bustling towns of Banchory and Aboyne. Within easy commuting distance of Westhill and Kingswells, the property has been sympathetically modernised to include modern day comforts whilst retaining much of the original character and charm. Warmly decorated, with natural wood finishes, and “Georgian “ style windows, the property has retained an original Inglenook granite fireplace in the lounge which has been fitted with a wood burning stove. A superb Dining Kitchen/Family Room is complemented by a charming lounge while a separate Dining Room leads, via French doors to a paved patio. A Bedroom and Bathroom are also located on the ground floor along with a Sun Porch and useful Utility Room. On the upper level there is a spacious Master Bedroom, two further Double Bedrooms and Bathroom. Externally, garden grounds extend to approximately two acres and incorporate a large garage, three sheds, drying area, lawns, woodland and a well stocked vegetable garden. • Detached Dwelling House • Oil Fired Central heating • Four Double Bedrooms • Septic Tank Drainage • 2 Acres Garden Ground • Mains Water Terms Council Tax Band F EPC Band E Entry By arrangement Viewing Contact Solicitors on 013398 87665 or 013398 83354/ 07775 734204 NB. Whilst these particulars are believed to be correct they are not guaranteed and do not form part -

Aboyne 22 Appendix 5

Winter Maintenance Operational Plan Issued 2016 7 Path BALNAGOWAN WAY 8 An Acail B 9094 9 Kildonan 16 10 8 9 Track 7 El Sub Sta GOLF CRESCENT 5 East Mains CASTLE CRESCENT 17 12 11 10 22 8 Schiehallion Cumbrae 10 6 6 5 2 1 6 15 FB 11 35 BALNAGOWAN DRIVE11 1 15 50 16 19 5 15 Cattle Grid GOLF PLACE 3 4 GOLF ROAD 31 2 26 21 7 23 37 Ardgrianach 1 1 4 20 1 Allachside 9 43 The Pines 4 16 18 17 Invergarry Cottage Alberta Huntlyfield Firhurst 1 24 27 22 18 130.2m 55 12 Highlands Formaston 10 Rosebank Pine Villa The Mill House Mill Lodge Alt-Mor Cottage Cottage The CHARLTON 4 2 Birches 123.7m LB 25 8 41 TCB 26 20 Pine Villa AVENUE Hawthorne 23 1 3 A 93 18 Willowbank Morvich 126.8m 8 4 Glen-Etive Laurelbank 2 The Pines CHARLTON CRESCENT 7 BALLATER ROAD 11 15 27 Burnview 15 11 Tigh-an-allt 21 7 5 Charleston 1 Lodge Hall LOW ROAD The Junipers SheilingThe East 1-2 Millburn Toll Glen Rosa Cottages El FB 123.7m Path (um) 1 to 3 5 1 Sub Woodend Dee View FB El Sub Sta Tennis Hillview Sta Path 1 Courts Charleston Buildings 8-9 BONTY PLACE 4 CottageStanley Warrendale Brimmond 4 Runchley 6 Pavilion Howe Burn Thistle 16 CairnwellGlas Down Path Well Bank Cottage Old Bakery 6 Industrial Estate Maol Pavilion PC Cottage EDGEWOOD PLACE CRES Bowling 12 14 Fountain Path Carnmohr Vale PO War Memorial Green Lilyvale TOLL Woodside Buildings (Hall) Bonty Cemetery 120.8m Allachburn Bank Court Firmaron Cottage (Old People's Home) WEST Arntilly 10 Rowanbank 11 Craighouse 11 1 Oakwood Car Park Shelter STATION SQUARE Southerton Woodland Dunmuir Glenisla Bridge LB View Bank -

Aberdeenshire)

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Kincardine O'Neil-Old Roads Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is a pleasant walk in a mixed rural landscape on Deeside. The ascent from the river to the old grazing pastures on the ridge of the Hill of Dess is gradual. There are good views throughout, and many historical associations. Duration: 2.5 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Frequent Stagecoach bus service along Deeside. Check timetables. On-street, or small car-park near the village hall, off The Spalings road. Length: 7.550 km / 4.72 mi. Height Gain: 163 meter. Height Loss: 163 meter. Max Height: 204 meter. Min Height: 94 meter. Surface: Moderate. On good paths and tracks. Good walking surfaces throughout and some sections have walking posts to assist route-finding. Difficulty: Medium. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance and overall ascent. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead on public roads and near to farm animals. Refreshments: Freshly made sandwiches in village shop. Also, newly opened cake shop across the road. Description This walk, in an elongated figure of eight, provides a range of country and riverside environments to enjoy in scenic Deeside. The walk starts and finishes at the historic ruin of the Church of St Mary in Kincardine O’Neil, the oldest village on Deeside. The present structure dates back to the 14thC but it is believed to have been a place of Christian worship from the 6thC. This walking route takes in a number of old roads, starting with Gallowhill Road, its purpose deriving from Medieval times when every feudal baron was required to erect a gibbet (gallows) for the execution of male criminals, and sink a well or pit, for the drowning of females! Soon after, the route follows a short section of the Old Deeside Road, now a farm track, which dates to before the great agricultural improvements that started in the 1700's. -

Norton House, 1 North Deeside Road, Kincardine O'neil, Aboyne, Aberdeenshire

NORTON HOUSE, 1 NORTH DEESIDE ROAD KINCARDINE O’NEIL, ABOYNE, ABERDEENSHIRE NORTON HOUSE, 1 NORTH DEESIDE ROAD, KINCARDINE O’NEIL, ABOYNE, ABERDEENSHIRE Detached Victorian 6/7 bedroom property with beautiful garden grounds in the heart of Royal Deeside. Aboyne 4 miles ■ Banchory 8 miles ■ Aberdeen 30 miles ■ 3 reception rooms. 6/7 bedrooms ■ Fine traditional property ■ Annex accommodation ■ Beautiful garden grounds ■ Around 1 acre in total ■ Royal Deeside location Aberdeen 01224 860710 [email protected] SITUATION Kincardine O’Neil is one of the oldest villages in Deeside and lies on the north side of the River Dee within the heart of Royal Deeside, between the desirable towns of Banchory, only 8 miles, and Aboyne, 4 miles. The location is about 10 minutes’ drive from the Cairngorms National park boundary and offers an array of outdoor leisure activities including salmon fishing on the River Dee, horse riding, mountain biking, forest and hill walking, good local and international golf courses, gliding, canoeing, shooting, skiing and snowboarding. The popular Deeside Way runs west through Kincardine O’Neil towards Aboyne and east toward Banchory, offering numerous walking, cycling and hacking options. In only a few minutes you can enjoy the trail along the North banks of the River Dee by foot or bike and the ski centres at Glenshee & the Lecht are within a short travelling distance.Schooling is provided at Kincardine O’Neil Primary School whilst secondary education is catered for at Aboyne Academy. Banchory Academy may be possible with the necessary applications. Private education is available in Aberdeen at Robert Gordon’s, St. -

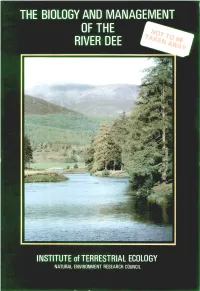

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

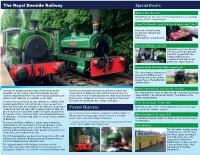

Final Deeside Railway Inside

The Royal Deeside Railway Special Events Mothers Day - March 26 Bring Mum and the rest of the family along for our opening service of 2017. Steam hauled Cream Tea Specials - April 15-16, May 28, July 16, Aug 13, Sep 17 Enjoy one of our famous Cream Teas onboard our Buet Car. Trains will be steam hauled. Victorian Weekend - June 3-4 Experience our recreation of the 1860s when the Deeside Line first opened with the railway sta in period costume Cream Teas in the Buet Car. Steam hauled. Deeside Steam & Vintage Rally - August 19-20 This ever-popular event takes place in the Milton Events Fieldadjacent to the station. Cream Teas in the Buet Car. Steam hauled. Return of Bon-Accord - September 30 - October 1 The Deeside Railway operates train services from April to The line was regularly patronised by the Royal Family and December on the original route of the Deeside Line. All other visitors to Balmoral Castle until it closed in 1966 as a We celebrate the return of “Bon-Accord”, our Victorian steam journeys depart from Milton of Crathes station and take 20-25 result of the notorious Beeching Report. Thirty years later the engine built for Aberdeen Gas Works, from duties in the minutes. Refreshments are available on the train. Royal Deeside Railway Preservation Society was formed and South. Steam hauled. the work of restoring the line commeced in 2003. Steam services are hauled by our resident loco 'Salmon', built End of Season Gala - October 14-15 by Andrew Barclay in 1942. Later in the season, we welcome back sister loco 'Bon-Accord' built for the Aberdeen Corporation Private Charters Non-stop steam services throughout the weekend to mark Gasworks in 1897 and owned by Grampian Transport Museum. -

Place-Names of the Cairngorms National Park

Place-Names of the Cairngorms National Park Place-Names in the Cairngorms This leaflet provides an introduction to the background, meanings and pronunciation of a selection of the place-names in the Cairngorms National Park including some of the settlements, hills, woodlands, rivers and lochs in the Angus Glens, Strathdon, Deeside, Glen Avon, Glen Livet, Badenoch and Strathspey. Place-names give us some insight into the culture, history, environment and wildlife of the Park. They were used to help identify natural and built landscape features and also to commemorate events and people. The names on today’s maps, as well as describing landscape features, remind us of some of the associated local folklore. For example, according to local tradition, the River Avon (Aan): Uisge Athfhinn – Water of the Very Bright One – is said to be named after Athfhinn, the wife of Fionn (the legendary Celtic warrior) who supposedly drowned while trying to cross this river. The name ‘Cairngorms’ was first coined by non-Gaelic speaking visitors around 200 years ago to refer collectively to the range of mountains that lie between Strathspey and Deeside. Some local people still call these mountains by their original Gaelic name – Am Monadh Ruadh or ‘The Russet- coloured Mountain Range’.These mountains form the heart of the Cairngorms National Park – Pàirc Nàiseanta a’ Mhonaidh Ruaidh. Invercauld Bridge over the River Dee Linguistic Heritage Some of the earliest place-names derive from the languages spoken by the Picts, who ruled large areas of Scotland north of the Forth at one time. The principal language spoken amongst the Picts seems to have been a ‘P-Celtic’ one (related to Welsh, Cornish, Breton and Gaulish). -

Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies

1 From mountain to sea Aberdeenshirep Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies December 2017 2 | Contents 1 BENEFITS 3 2 CHILDCARE AND RESPITE 23 3 COMMUNITY ACTION 43 4 COMPLAINTS 50 5 EDUCATION AND LEARNING 63 6 Careers 81 7 FINANCIAL HELP 83 8 GENERAL SUPPORT 103 9 HEALTH 180 10 HOLIDAYS 194 11 HOUSING 202 12 LEGAL ASSISTANCE AND ADVICE 218 13 NATIONAL AND LOCAL SUPPORT GROUPS (SPECIFIC CONDITIONS) 223 14 SOCIAL AND LEISURE OPPORTUNITIES 405 15 SOCIAL WORK 453 16 TRANSPORT 458 SEARCH INSTRUCTIONS 1. Right click on the document and select the word ‘Find’ (using a left click) 2. A dialogue box will appear at the top right hand side of the page 3. Enter the search word to the dialogue box and press the return key 4. The first reference will be highlighted for you to select 5. If the first reference is not required, return to the dialogue box and click below it on ‘Next’ to move through the document, or ‘previous’ to return 1 BENEFITS 1.1 Advice for Scotland (Citizens Advice Bureau) Information on benefits and tax credits for different groups of people including: Unemployed, sick or disabled people; help with council tax and housing costs; national insurance; payment of benefits; problems with benefits. http://www.adviceguide.org.uk 1.2 Attendance Allowance Eligibility You can get Attendance Allowance if you’re 65 or over and the following apply: you have a physical disability (including sensory disability, e.g. blindness), a mental disability (including learning difficulties), or both your disability is severe enough for you to need help caring for yourself or someone to supervise you, for your own or someone else’s safety Use the benefits adviser online to check your eligibility. -

The Parish of Durris

THE PARISH OF DURRIS Some Historical Sketches ROBIN JACKSON Acknowledgments I am particularly grateful for the generous financial support given by The Cowdray Trust and The Laitt Legacy that enabled the printing of this book. Writing this history would not have been possible without the very considerable assistance, advice and encouragement offered by a wide range of individuals and to them I extend my sincere gratitude. If there are any omissions, I apologise. Sir William Arbuthnott, WikiTree Diane Baptie, Scots Archives Search, Edinburgh Rev. Jean Boyd, Minister, Drumoak-Durris Church Gordon Casely, Herald Strategy Ltd Neville Cullingford, ROC Archives Margaret Davidson, Grampian Ancestry Norman Davidson, Huntly, Aberdeenshire Dr David Davies, Chair of Research Committee, Society for Nautical Research Stephen Deed, Librarian, Archive and Museum Service, Royal College of Physicians Stuart Donald, Archivist, Diocesan Archives, Aberdeen Dr Lydia Ferguson, Principal Librarian, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Harper, Durris, Kincardineshire Nancy Jackson, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Katy Kavanagh, Archivist, Aberdeen City Council Lorna Kinnaird, Dunedin Links Genealogy, Edinburgh Moira Kite, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire David Langrish, National Archives, London Dr David Mitchell, Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Margaret Moles, Archivist, Wiltshire Council Marion McNeil, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Effie Moneypenny, Stuart Yacht Research Group Gay Murton, Aberdeen and North East Scotland Family History Society, -

Medieval Burgh : Staff, Students Andthegeneral Public

AB DN VisitAberdeen // Weekend Aberdeen Old Town 04 Sports Village 34 Cathedrals 06 AFC 36 Ancestral 08 Satrosphere 38 Universities 10 Transition Extreme 40 //YOUR VISIT Walks + Beach Walks 12 Shopping 42 Parks 14 The Merchant Quarter 44 HMT and Music Hall 16 Whisky 46 Happy to meet, sorry to part, happy Live Events 18 Castles 48 to meet again; that is the official Art Gallery 20 Royal Deeside 50 toast of the city of Aberdeen and Maritime Museum 22 Wildlife 52 one you won’t forget after your Gordon Highlanders 24 Banffshire Coast 54 own visit. From its vibrant nightlife, Harbour 26 Stonehaven 56 historic architecture and abundance Urban Dolphins + 28 Skiing 58 of culture, you’re truly spoilt for Harbour Cruises Food 60 Drink 62 choice in the city. Aberdeen is also :contents Fittie 30 Local Produce 64 Golf 32 packed full of lovely places to stay, Map 66 fantastic restaurants with a range of delicious menus from around the world and fun-filled activities to keep your itinerary thoroughly entertaining. You’ll be safe in the knowledge that Aberdeen’s Visitor Information Centre located on Union Street, is staffed by local experts who are more than willing to help you explore what the city has to offer. Alternatively you can bookmark www.visitaberdeen. com on your phone or download the MyAberdeen mobile app. So what are you waiting for? Enjoy your visit! Steve Harris, Chief Executive 3 //OLD TOWN The history of Aberdeen has Robert The Bruce was Aberdeen’s greatest benefactor always been a tale of two gifting Royal lands to the people in 1319 after they cities, whose modern role helped him repel English invaders.