Verbatim and Māori Theatre Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Mason, James K. Baxter, Mervyn Thompson, Renée and Robert Lord, Five Playwrights

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. METAMORPHOSIS AT 'THE MARGIN': BRUCE MASON, JAMES K. BAXTER, MERVYN THOMPSON, RENtE AND ROBERT LORD, FIVE PLAYWRIGHTS WHO HAVE HELPED TO CHANGE THE FACE OF NEW ZEALAND DRAMA. A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy III English at Massey University [Palmerston North], New Zealand Susan Lillian Williams 2006 11 DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my grandfather and my mother, neither of whom had the privilege of gaining the education that they both so much deserved. I stand on their shoulders, just as my son, David, will stand on mine. The writing of this thesis, however, would not have been possible without the unstinting assistance of Ainslie Hewton. Finally, to my irreplaceable friend,Zeb, the puppy I wanted and never had as a child. Zeb nurtured me throughout this long project and then, in the last week of completion, was called by the black rabbit. Thank you for everything you taught me Zebedee. You and I will always be playing alongside your beloved riverbank. III ABSTRACT Drama has been the slowest of the arts to develop an authentic New Zealand 'voice.' This thesis focuses on the work of five playwrights: Bruce Mason, James K. Baxter, Mervyn Thompson, Renee and Robert Lord, all of whom have set out to identify such a 'voice' and in so doing have brought about a metamorphosis in the nature of New Zealand drama. -

Chapter 13: Drama and Theatre in and for Schools:

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Drama and Theatre in and for Schools: Referencing the nature of theatre in contemporary New Zealand A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Degree Master of Arts in Theatre Studies) at The University of Waikato by Jane Isobel Luton _________ The University of Waikato 2010 Abstract This thesis considers the nature of drama and theatre in and for schools and references the nature of theatre in contemporary New Zealand. Drama in schools in New Zealand has developed from the earliest school productions in the 1800's, through its perceived role to enrich lives, to becoming a discrete Arts subject within the New Zealand educational curriculum in 1999. -

(No. 6)Craccum-1986-060-006.Pdf

m mm or kwmm w r a K m r Of w m m - 4 APR 1986 * A f'R 1986 a m * u t t t f r Auckland University Students Association, Incorporated FREE Our Beloved VOL 60, NO. 6: 1 APRIL, 1986. Deputy-Leader, Nuclear Scientist rejects "Star Richard Steel, Wars". EDITORS shows intrepid determination in page 3 Nuclear Scientist Rejects VIEW fighting corruption "Star W ars". CRACCUM is a source of free expression and information for the Auckland University Dr Hugh de W itt, Senior Physicist Students and the University Community. — The SHOCK story on page 23. at the Livermore National Laboratory, said that the concept of a "perfect This weeks CRACCUM featuring the population defence of the United States is technically unfeasible for ★ Arts in Review many decades, if not a century." ★ Music While on a brief visit to Auckland, RICHARD STEEL he spoke with Craccum reporter ★ Theatres’ Film Galleries Elizabeth Pritchett. Dr de Witt has I f , access to classified material on nuclear ★ Books MURDER weapons research being carried out at Livermore, although he does not work ★ t .v . in Quad ? on nuclear arms developm ent. Intrigue surrounds "Continuation of S tar W ars is ★ Previews Anti-Watson moves. endangering arms control After discussing the petitidn of 20 negotiations," he said. See next members calling for a Special General week's Craccum for the interview. Meeting of the Association, Executive decided not to call a meeting because, subsequently and before Executive had a t met to discuss the petition, a letter was 'S\ received from three of the petitioners wishing to withdraw their names, announced the AUSA Secretary, Pilar An Award for Alba. -

Broadcasting Our Reo and Culture

Putanga 08 2008 CELEBRATING MÄORI ACHIEVEMENT Paenga Whäwhä – Haratua Paenga BROADCASTING OUR REO AND CULTURE 28 MÄORI BATTALION WAIKATO MÄORI NETBALL E WHAKANUI ANA I TE MÄORI 10 FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE – LEITH COMER Putanga GOING FORWARD TOGETHER 08 Tënä tätou katoa, Te Puni Kökiri currently has four bills being considered by 2008 Parliament – the Mäori Trustee and Mäori Development Bill, the Stories in Kökiri highlight the exciting and Mäori Purposes Bill (No 2), the Mauao Historic Reserve Vesting Bill inspirational achievement of Mäori throughout and the Waka Umanga (Mäori Corporations) Bill. New Zealand. Kökiri will continue to be a reservoir These bills, along with other Te Puni Kökiri work programmes, Paenga Whäwhä – Haratua Paenga of Mäori achievement across all economic, social highlight Mäori community priorities, including rangatiratanga, and cultural areas. iwi and Mäori identity, and whänau well-being, while The feedback we are getting is very supportive and encompassing government priorities including national identity, positive and it reinforces the continuation of our families – young and old, and economic transformation. Kökiri publication in its current form. We feel sure that the passage of these bills will lead to more Behind the scenes in areas that do not capture much success stories appearing in Kökiri where Mäori have put the public attention is a lot of important and worthwhile legislative changes to good effect in their communities. policy and legislative work that Te Puni Kökiri is intimately involved in. Leith Comer Te Puni Kökiri – Manahautü 2 TE PUNI KÖKIRI | KÖKIRI | PAENGA WHÄWHÄ – HARATUA 2008 NGÄ KAUPAPA 5 16 46 28 Mäori Battalion 5 Waikato 16 Mäori Netball 46 The 28th annual reunion of 28 Mäori In this edition we profi le Aotearoa Mäori Netball celebrated Battalion veterans, whänau and Te Puni Kökiri’s Waikato region – its 21st National Tournament in Te friends was hosted by Te Tairäwhiti’s its people, businesses, successes Taitokerau with a fantastic display of C Company at Gisborne’s Te Poho and achievements. -

This Online Version of the Thesis Uses Different Fonts from the Printed Version Held in Griffith University Library, and the Pagination Is Slightly Different

NOTE: This online version of the thesis uses different fonts from the printed version held in Griffith University Library, and the pagination is slightly different. The content is otherwise exactly the same. Journeys into a Third Space A study of how theatre enables us to interpret the emergent space between cultures Janinka Greenwood M.A., Dip Ed, Dip Tchg, Dip TESL This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1999 Statement This work has not been previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university, To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. Janinka Greenwood 17 December 1999 Acknowledgments Thanks are due to a number of people who have given me support and encouragement in completing this thesis. Firstly I am very grateful for the sustained encouragement and scholarly challenges given by my principal supervisor Associate Professor John O’Toole and also by my co-supervisor Dr Philip Taylor. I appreciate not only their breadth of knowledge in the field of drama, but also their courageous entry into a territory of cultural differences and their insistence that I make explicit cultural concepts that I had previously taken for granted. I am grateful also to Professor Ranginui Walker who, at a stage of the research when I felt the distance between Australia and New Zealand, consented to “look over my shoulder”. Secondly, my sincere thanks go to all those who shared information, ideas and enthusiasms with me during the interviews that are reported in this thesis and to the student teachers who explored with me the drama project that forms the final stage of the study. -

Seeing Ourselves on Stage

Seeing Ourselves on Stage: Revealing Ideas about Pākehā Cultural Identity through Theatrical Performance Adriann Anne Herron Smith Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Otago 2010 Acknowledgements Thanks to my Kaitiaki Rangimoana Taylor My Supervisors: Henry Johnson, Jerry Jaffe, Erich Kolig (2004-July 2006), Martin Tolich (July 2007 onwards) Thanks to my children Ruth Kathryne Cook and Madeline Anne Hinehauone Cook for supporting me in this work. Thanks also to Hilary Halba and Alison East for their help, encouragement and invigorating discussion; to friend and poet Roma Potiki who offered the title for this thesis and also engaged in spirited discussion about its contents; to Monika Smith, Adrienne Jansen, Geesina Zimmermann, Annie Hay Mackenzie and to all of my friends who have supported this project; Thanks to Louise Kewene, Trevor Deaker, Martyn Roberts and Morag Anne Baillie for technical support during this project. Thanks to all of the artists who have made this work possible: Christopher Blake, Gary Henderson, Lyne Pringle, Kilda Northcott, Andrew London and to Hilary Norris, Hilary Halba, Alison East and Lisa Warrington who contributed their time, experience and passion for the work of Aotearoa/New Zealand to this endeavour. ii Abstract This is the first detailed study of New Zealand theatrical performance that has investigated the concepts of a Pākehā worldview. It thus contributes to the growing body of critical analysis of the theatre Aotearoa/New Zealand, and to an overall picture of Pākehā New Zealander cultural identity. The researcher‘s experience of being Pākehā has formed the lens through which these performance works are viewed. -

Matt Chamberlain. Height 182 Cm

Actor Biography Matt Chamberlain. Height 182 cm Feature Film. 2010 Hook Line and Sinker Frank Torchlight Productions Dir. Andrea Bosshard/Shane Loader 2009 Insatiable Moon Tony De Villiers The Insatiable Moon Ltd (Support) Dir. Rosemary Riddell Prd. Mike Riddell, Pip Piper&Rob Taylor 2008 Under The Mountain Uncle Cliff Redhead Films Ltd (Support) Dir. Jonathan King Prd. Richard Fletcher 2007 Avatar Lieutenant Colonel 880 Productions Dir. James Cameron 2006 Black Sheep Oliver Oldsworth Live Stock Films (Support) Dir. Jonathan King Prd. Philippa Campbell 2004 King Kong Venture Crew Big Primate Pictures (Support) Dir. Peter Jackson 2003 In My Fathers Den Jeff IMFD Productions/UK (Support) Dir. Brad McGann 2000 Stickmen Hugh Stick Films Dir. Hamish Rothwell 1995 Frighteners Wayne WingNut Films Dir. Peter Jackson 1993 The Last Tattoo Helmsman Capella International /Plumb Productions (Support) Dir. John Reid PO Box 78340, Grey Lynn, www.johnsonlaird.com Tel +64 9 376 0882 Auckland 1245, NewZealand. www.johnsonlaird.co.nz Fax +64 9 378 0881 Matt Chamberlain. Page 2 Short Film. 2011 Stumped Farmer This Tall To Ride Productions (Lead) Dir. Jack Nicol 1992 Rush Hour New Zealand Drama School Productions Dir. Ian Mune Television. 2021 One Lane Bridge Season 2 D. I Preston Great Southern Television NZ (Recurring Guest) Dir. Peter Burger 2019 One Lane Bridge D I David Preston Great Southern Television Dir. Various Prd. Carmen Leonard 2018 Murder is Forever Leo Fisher Dir. Chis Dudman Prd. Netflix 2017 The Interns Performer TVNZ Prd. Gareth Williams & Tim Batt 2017 Roman Empire 2 Germanicus Stephen David Entertainment (Guest) Dir. John Ealer Prd. -

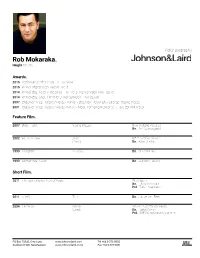

Rob Mokaraka. Height 180 Cm

Actor Biography Rob Mokaraka. Height 180 cm Awards. 2015 Performance of the Year - All Our Sons 2015 Winner of Best Actor Award - Inc 'd 2014 Winner-Best Actor in the Short Film INC 'D, Wairoa Maori Film Festival 2014 Winner-Best Short Film INC 'D, Wairoa Maori Film Festival 2007 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards - Winner - Best New Playwright - Strange Resting Places 2001 Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards -Winner - Most Promising Newcomer - Have Car Will Travel Feature Film. 2007 Bride Flight Young Mozzie New Holland Pictures Dir. Ben Sombogaart 2002 Aidiko Insane Jobs NZ Film Commission (Pimp) Dir. Adam Larkin 1999 A Night In Voo Doo Dir. Mike Wallace 1999 Speechless, Nurse Dir. Graham Tuckett Short Film. 2011 The Lawn Mower Men Of Kapu Blue Batch Dir. Libby Hakaraia Prd. Tainui Stephens 2011 UpHill Tim Dir. Jackie Van Beek 2004 Tama Tu Waika Aio Films /Defender Films (Lead) Dir. Taika Cohen Prd. Cliff Curtis&Ainsley Gardiner PO Box 78340, Grey Lynn, www.johnsonlaird.com Tel +64 9 376 0882 Auckland 1245, NewZealand. www.johnsonlaird.co.nz Fax +64 9 378 0881 Rob Mokaraka. Page 2 Short continued... 2002 The Freezer Rob MF Films Dir. Paolo Rotondo Television. 2018 It Takes a Village Ropata Awa Films Dir. Tammy Davis Prd. Julian Arahanga 2018 The Dead Lands Hako Randolph TDL Limited Dir. Peter Meteherangi Taiko Burger, Michael Hurst Prd. Matthew Metcalfe, Fraser Brown 2014 When We Go to War Maori Captain Jump Film and TV Limited Dir. Peter Burger Prd. Robin Scholes and Janine Dickins 2011 Nga Reo Hou-Strange Resting Places Various Eyeworks New Zealand Ltd /Black Inc Media Ltd Dir. -

The Bicultural Landscape & Māori Theatre

The bicultural landscape & Māori theatre Note: Teachers can decide for themselves when to provide this contextual material to their class in relation to the work on the plays – before (to set the context), during (as issues arise), or after (as a discovery from the plays) – depending on individual class dynamics and teacher planning preferences. The interest in working with Purapurawhetū and The Pohutukawa Tree together is that they stand fifty years apart in the history of New Zealand theatre, and show fifty years of difference in the way they evoke New Zealand identity. We can take them as marker posts in defining our bicultural landscape. A working definition of ‘bicultural’ We live in a country that draws on both Māori and ‘Western’ cultures for its mainstream heritages. We call that two-fold cultural heritage ‘biculturalism’. Although many diverse immigrant groups fit into the mix of New Zealand society, the value systems and history that define our national identity are Māori and ‘Western’. The term ‘Western’ does not, of course, refer only the geographical west of Europe (which is the origin of the term) – it has become a way of naming the English-speaking global culture. In New Zealand we call it Pākehā. The relationship between the two cultures, as we know, is not stable. It is always changing, just as the cultures themselves are changing. The term ‘bicultural’ describes this interaction, not a place of arrival. This section of the project offers a brief history of the way theatre has approached bicultural interaction in New Zealand, and invites the making of new performances that describe that interaction – both as it has been in the past and as it may be in the future. -

Annual Report 2017–2018

Annual Report 2017–2018 1 Image: The Breaker Upperers 2 Cover Image: Waru G19 Report of the New Zealand Film Commission for the year ended 30 June 2018 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June 2018. Kerry Prendergast Tom Greally ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• CHAIR BOARD MEMBER NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2017/18 33 Highlights • The New Zealand Film Commission launched its Te Rautaki Māori, a strategy based on developing an ongoing partnership with the Māori screen industry. To support the strategy, new funding opportunities and support for Māori filmmakers were also announced. • Karen Waaka-Tibble became the NZFC’s inaugural Pou Whakahare, a role established to assist in implementing Te Rautaki Māori. • The 125 Fund, a feature film fund for projects where at least two of the key creatives, including the director, are women was launched, and opened for applications in June. • Eleven feature films (including four documentaries) with NZFC production financing were released theatrically in New Zealand in the period. The title which generated the highest box office wasThe Breaker Upperers with a gross of $1,762,706 (to 30 June 2018). • The New Zealand Screen Production Grant (NZSPG) International attracted New Zealand Qualifying Production Expenditure (NZQPE) totalling $693,892,538 in the period, which triggered grant payments of $149,265,574. • 42 final NZSPG certificates were issued, 13 to New Zealand productions and 29 to international productions. -

Breaking the Stage: from Te Matatini to Footprints/Tapuwae

7. Breaking the Stage: From Te Matatini to Footprints/Tapuwae TE RITA PAPESCH, SHARON MAZER The post-imperial writers of the Third World therefore bear their past within them – as scars of humiliating wounds, as instigation for different practices, as potentially revised visions of the past tending towards a post-colonial future, as urgently reinterpretable and redeployable experiences, in which the formerly silent native speaks and acts on territory reclaimed as part of a general movement of resistance, from the colonist.1 You can take my marae to the stage but don’t bring the stage to my marae.2 Mihi Kei te mingenga e pae nei, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa. Ahakoa i tukuna ngā mihi i nākuanei kua riro māku anō te mihi nā māua ki a koutou i tēneki wā, nā reira, nau mai, haere mai ki ‘Ka Haka – Empowering Performance’. Ko te tūmanako ka areare ngō koutou taringa ki ngā māua kōrero. Ki te kore waiho ngā kōrero ki ngā pā tū o te whare neki ki reira 1 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (1993. London: Vintage, 1994) 256. 2 John Te Ruruhe Rangihau, personal communication with Te Rita Papesch, 2007. 108 Breaking the Stage: From Te Matatini to Footprints/Tapuwae iri atu ai hei kohinga kōrero mā ngā uri whakaheke. Kāti. Ka huri ki a Sharon māna tā māua kauwhau e whakatūwhera.3 Kaupapa There’s too much talk of decolonising the stage, as if the theatre were not itself a colonial artefact, a hangover from the settlers’ desire to appear civilised in what they saw as a savage land. -

Rituals of the New Zealand Maori

New Zealand Māori Marae Rituals applied to Theatre Jane Boston in conversation with Annie Ruth to discuss how the social improvisatory framework of encounters on the marae (Maori meeting place) can teach theatre practitioners a great deal about meeting and connecting with audiences. The combination of structure and improvisation, aligned to clarity around role and purpose, can shift the paradigm of the encounter. This event took place at Central School of Speech & Drama on 25 October 2011. Improvisation and structure Karanga (0.00 – 1.57) Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa Welcome, thrice welcome Kō te ipu kawe korero e poipoi ne May the pitcher of our talk nourish us Te kaupapa o te wā With the processes that we share Haria mai ra ngā kotou kete kōreo Bring out the baskets to fill with our mutual talk. E noho tahi tatou e Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa Again welcome, thrice welcome. Whaikōrero Ka mihi tuatahi kia Papatuanuku e takoto nei I greet the earth mother beneath us raua ko Ranginui ki runga and the sky father above us. Te whare ō Central School of Speech & I greet the house of Central tena koe School of Speech and Drama Annie Ruth - A huge welcome to you and thank you for coming today, I want to acknowledge you in the words that I said before. I acknowledged our ancestors yours and mine, I acknowledged the earth mother and the sky father and this place in which we are now gathered. I started with a Karanga with words that were particularly given to me to use in these kinds of occasions, Because this is not when you normally do a Karanga, but I wanted to do something of that sort to give you a visceral feel of what some elements of the Pōwhiri are like so you know a little of what I’m talking about as we go forward.