ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Allegro Maestoso 2. Concerto N 1 Pour Piano Et Orchestre

DISC: 1 1. Concerto n 1 pour piano et orchestre en mi bemol majeur - 1. allegro maestoso 2. Concerto n 1 pour piano et orchestre en mi bemol majeur - Argerich Martha 3. Concerto n 1 pour piano et orchestre en mi bemol majeur - Argerich Martha 4. Concerto n 1 pour piano et orchestre en mi bemol majeur - allegro marziale animato - Argerich Martha 5. Concerto pour piano et orchestre en sol majeur - 1. allegramente - Abbado Claudio 6. Concerto pour piano et orchestre en sol majeur - 2. adagio assai - Abbado Claudio 7. Concerto pour piano et orchestre en sol majeur - 3. presto - Abbado Claudio 8. Concerto pour piano et orchestre n 3 op 30 en re mineur - 1. allegro ma non tanto - Chailly Riccardo 9. Concerto pour piano et orchestre n 3 op 30 en re mineur - 2. intermezzo (adagio) - Chailly Riccardo 10. Concerto pour piano et orchestre n 3 op 30 en re mineur - 3. finale (alla breve) - Chailly Riccardo DISC: 2 1. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - sinfonia - Argerich Martha 2. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - allemande - Argerich Martha 3. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - courante - Argerich Martha 4. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - sarabande - Argerich Martha 5. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - rondeau - Argerich Martha 6. Partita n 2 bwv 826 en ut mineur - capriccio - Argerich Martha 7. Sonatine - modere - Argerich Martha 8. Sonatine - mouvement de menuet - Argerich Martha 9. Sonatine - anime - Argerich Martha 10. Gaspard de la nuit 3 poemes pour piano - ondine - Argerich Martha 11. -

András Schiff, Piano II

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Wednesday, February 29, 2012, 8pm Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Thirty-Three Variations on a Waltz by Zellerbach Hall Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 (1819, 1822–1823) Thema — Vivace I. Alla Marcia maestoso András Schiff, piano II. Poco Allegro III. L’istesso tempo IV. Un poco più vivace V. Allegro vivace PROGRAM VI. Allegro ma non troppo e seriouso VII. Un poco più allegro VIII. Poco vivace Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Three-Part Inventions (Sinfonias), IX. Allegro pesante e risoluto bwv 787–801 (1720) X. Presto XI. Allegretto No. 1 in C major, bwv 787 XII. Un poco più moto No. 2 in C minor, bwv 788 XIII. Vivace No. 3 in D major, bwv 789 XIV. Grave e maestoso No. 4 in D minor, bwv 790 XV. Presto scherzando No. 5 in E-flat major,bwv 791 XVI. Allegro No. 6 in E major, bwv 792 XVII. Allegro No. 7 in E minor, bwv 793 XVIII. Poco moderato No. 8 in F major, bwv 794 XIX. Presto No. 9 in F minor, bwv 795 XX. Andante No. 10 in G major, bwv 796 XXI. Allegro con brio — meno allegro No. 11 in G minor, bwv 797 XXII. Allegro molto (alla “Notte e giorno faticar” No. 12 in A major, bwv 798 from Mozart’s Don Giovanni) No. 13 in A minor, bwv 799 XXIII. Allegro assai No. 14 in B-flat major,bwv 800 XXIV. Fughetta. Andante No. 15 in B minor, bwv 801 X X V. A llegro XXVI. (Piacevole) XXVII. Vivace Béla Bartók (1881–1945) Sonata for Piano, Sz. -

Peter Serkin, Piano Thema — Vivace I

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Tuesday, May 8, 2012, 8pm Hertz Hall Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Thirty-Three Variations on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 (1819, 1822–1823) Peter Serkin, piano Thema — Vivace I. Alla Marcia maestoso II. Poco Allegro III. L’istesso tempo IV. Un poco più vivace PROGRAM V. Allegro vivace VI. Allegro ma non troppo e seriouso VII. Un poco più allegro Oliver Knussen (b. 1952) Variations for Piano, Op. 24 (1989) VIII. Poco vivace IX. Allegro pesante e risoluto X. Presto XI. Allegretto Toru Takemitsu (1930–1996) For Away (1972) XII. Un poco più moto XIII. Vivace XIV. Grave e maestoso XV. Presto scherzando Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) Adagio (2011) XVI. Allegro XVII. Allegro XVIII. Poco moderato XIX. Presto INTERMISSION XX. Andante XXI. Allegro con brio — meno allegro XXII. Allegro molto (alla “Notte e giorno faticar” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni) XXIII. Allegro assai XXIV. Fughetta. Andante X X V. A llegro XXVI. (Piacevole) Funded by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ XXVII. Vivace 2011–2012 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. XXVIII. Allegro XXIX. Adagio ma non troppo Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. XXX. Andante, sempre cantabile XXXI. Largo, molto espressivo XXXII. Fuga. Allegro XXXIII. Tempo di Minuetto moderato 20 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 21 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Oliver Knussen (b. 1952) Contemporary Music Group, and holder of adage that East and West would never meet by of 1957, inspired by the death of his friend and Variations for Piano, Op. -

Beethoven Classical Music: Be an Instant Expert

CLASSICAL MUSIC: BE AN BEETHOVEN INSTANT EXPERT About the Instant Expert Series Many people think that learning about classical music and the people that create it would require so much time and energy that the prospect of diving in overwhelms them. Naxos, the world’s leading classical label, has mined its vast catalog of recordings (and the brains of its global staff of classical music connoisseurs) to design a new series called “Instant Expert” which is available by Beethoven download only. Each “Instant Expert” volume focuses on the music of one composer, featuring a Classical Music: Be An curated collection of that composer’s greatest hits as well as some unique or historically significant Instant Expert compositions. In addition, each download is accompanied by a podcast hosted by Raymond Bisha, Naxos of America Director of Media Relations, and a booklet containing track information and an abridged biography of the composer. – Kelly M. Rach, National Publicist, Naxos of America –2– Ludwig van Beethoven (12/17/1770 - 3/26/1827) Born in Bonn in 1770, the eldest son of a singer in the Kapelle of the Archbishop-Elector of Beethoven Cologne and grandson of the Archbishop’s Kapellmeister, Beethoven moved in 1792 to Classical Music: Be An Vienna. There he had some lessons from Haydn Instant Expert and others, quickly establishing himself as a remarkable keyboard player and original composer. By 1815 increasing deafness had made public performance impossible and accentuated existing eccentricities of character, patiently tolerated by a series of rich patrons and his royal pupil the Archduke Rudolph. Beethoven did much to enlarge the possibilities of music and widen the horizons of later generations of composers. -

RONALD BRAUTIGAM Fortepiano the RAGE OVER a LOST PENNY

RONALD BRAUTIGAM fortepiano THE RAGE OVER A LOST PENNY RONDOS & KLAVIERSTÜCKE BIS-1892 2013-12-18 11.17 BIS-1892_f-b.indd 1 van BEETHOVEN, Ludwig (1770–1827) Complete Works for Solo Piano – Volume 13 Rondos & Klavierstücke 1 Rondo in C major, WoO 48 (1783) 2'30 Allegretto 2 Rondo in A major, WoO 49 (1783) 2'41 Allegretto 3 Rondo in B flat major, Kinsky-Halm Anh. 6 7'10 4 Rondo in C major, Op. 51 No. 1 (1796–97) 5'58 Moderato e grazioso 5 Rondo in G major, Op. 51 No. 2 (1800?) 9'06 Andante cantabile e grazioso Der Gräfin Henriette v. Lichnowsky gewidmet 6 Rondo a capriccio in G major, Op. 129 (1795–98?) 5'59 „Alla ingharese quasi un capriccio“ („Die Wut über den verlorenen Groschen, ausgetobt in einer Caprice“) 7 Ecossaise in E flat major, WoO 86 (1825) 0'20 8 Six Ecossaises, WoO 83 (c. 1806?) 2'09 2 9 Andante in F major, WoO 57 (1809) 8'50 „Andante favori“ Andante grazioso con moto 10 Fantasie, Op. 77 (1800?) 9'40 Dem Grafen Franz v. Brunsvik gewidmet 11 Polonaise in C major, Op. 89 (1814) 5'21 Alla Polacca, vivace Der Kaiserin Elisabeth Alexiewna von Russland gewidmet 12 Klavierstück ‘Für Elise’ 3'35 (1810, rev. version of 1822, ed. Barry Cooper) (Novello) Molto grazioso 13 Andante maestoso in C major (1826) 3'11 („Ludwig van Beethoven’s letzter musikalischer Gedanke“) TT: 68'28 Ronald Brautigam fortepiano [1–8] Instrument by Paul McNulty (No. 161), after Walter & Sohn, c. 1805 (see page 28) [9–13] Instrument by Paul McNulty (No. -

' R Kû ¾Wˆp ¼,Æðþë

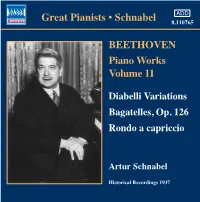

110765 bk Schnabel 9/05/2005 09:09am Page 5 Producer’s Note Artur Schnabel: BEETHOVEN: Piano Works, Vol. 11 ADD Artur Schnabel’s pioneering Beethoven Sonata Society recordings were originally issued on 204 78 rpm sides in Thirty-Three Variations on a Waltz by ¤ Variation 31: Largo, molto espressivo 5:29 Great Pianists • Schnabel fifteen volumes, each containing six or seven discs. The first twelve sets contained the thirty-two sonatas, usually Anton Diabelli in C major, Op. 120 ‹ Variation 32: Fuga. Allegro; Poco adagio 2:49 8.110765 packaged as one early, one middle and one late sonata per album. Variations, bagatelles and sundry short pieces › Variation 33: Tempo di Minuetto moderato, occupied the final three volumes. The sets were released in the UK on His Master’s Voice with some volumes also 1 Tema. Vivace 0:54 ma non tirarsi dietro 3:46 being issued on French Disque Gramophone, German Electrola and (for the Hammerklavier Sonata only) Victor in 2 Variation 1: Alla Marcia maestoso 1:41 the United States. In this eleven-CD reissue series, the first nine discs have been devoted to the sonatas, presented 3 Variation 2: Poco allegro 1:13 Recorded 30th October and 2nd November, 1937 in in their order of composition, while the final two volumes feature the other works. 4 Variation 3: L’istesso tempo 1:17 EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 BEETHOVEN Because the original discs rarely turn up in any form other than British pressings, the problem of how to deal 5 Variation 4: Un poco più allegro 1:03 Matrices: 2EA 5540-1, 5541-1, 5542-1, 5543-1, 5544-1, with the higher-than-average level of surface crackle inherent in HMV shellac has led previous transfer engineers 6 Variation 5: Allegro vivace 0:54 5545-3, 5546-2, 5547-2, 5548-1, 5549-1, 5550-1, 5551-1, down one of two paths. -

Franz LISZT (1811-1886)

DOCUMENTS SUR Franz LISZT (1811-1886) (Mise à jour le 20 mai 2013) Médiathèque Musicale Mahler 11 bis, rue Vézelay – F-75008 Paris – (+33) (0)1.53.89.09.10 www.mediathequemahler.org Médiathèques Musicale Mahler – Franz Liszt 2011 Livres et documents sur Franz LISZT (1811-1886) LIVRES Sur Franz Liszt 3 Liszt dans les biographies d'autres compositeurs 14 Liszt dans les ouvrages thématiques 17 PARTITIONS 25 ENREGISTREMENTS SONORES 45 Liszt dans les disques d'autres compositeurs 75 REVUES 94 ARCHIVES NUMÉRISÉES 95 FONDS D'ARCHIVES 97 2 Médiathèques Musicale Mahler – Franz Liszt 2011 LIVRES BIOGRAPHIES DE FRANZ LISZT Anna Maria Liszt, die Mutter des Musikers : ein Leben in Briefen : Katalog der Ausstellung, 24. 4. - 30. 9. 1986, Historisches Museum Krems, Dominikanerkirche, Körnermarkt. - Wien Krems : Niederösterreich-Gesellschaft für Kunst und Kultur : Historisches Museum, 1986. - (BM LIS A6) Franz Liszt / préf. de S. Gut. - Paris : Place, 2002. - (BM LIS E3) Franz Liszt : ein Genie aus dem pannonischen Raum Kindheit und Jugend : Katalog der Landessonderausstellung, aus Anlass des Liszt-Jahres 1986, 100. Todestag 31. Juli, 175. Geburtstag 22. Oktober. - Eisenstadt : Burgerländische Landesmuseen, 1986. - (BM LIS A4) Franz Liszt Kring : speciale uitgave ter gelegenheid van het festival op vrijdag17 en zondag 19 oktober 1980 in Utrecht met de programmatoelichtingen. - Utrecht : Liszt Kring, 1980. - (BM LIS A5) Franz Liszt. - München : Text + kritik, 1980. - (BM LIS E1) Franz Liszt. - Wien : Lafite, 1961. - (BM LIS E4) L'Education musicale, n° 570, mars-avril 2011. - Paris : Beauchesne, 2011. - (BM LIS E5) Les Amours d'une cosaque. - Paris : Degorce-Cadot, 1875. - (BM LIS C X2 (Réserve)) Liszt. -

Program Notes © 2021 Keith Horner

Rockport Music Program Page 40th ANNUAL ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL Friday, September 3 :: 5 & 8 PM JAN LISIECKI, piano RONDO A CAPRICCIO, OP. 129 (‘THE RAGE OVER A LOST PENNY’) (C1795) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) RONDO CAPRICCIOSO, OP. 14 (1828-30) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) LIEDER OHNE WORTE (SONGS WITHOUT WORDS), BOOK 6, OP. 67 (PUBL. 1845) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) No. 31, in E-flat major, Op. 67, No. 1 No. 32, in F-sharp minor, Op. 67, No. 2 No. 33, in B-flat major, Op. 67, No. 3 No. 34, in C major, Op. 67, No. 4, Spinnerlied (Spinning Song) No. 35, in B minor, Op. 67, No. 5 No. 36, in E major, Op. 62, No. 6 NOCTURNE IN B MAJOR, OP. 62 NO. 1 (1846) NOCTURNE IN E MAJOR, OP. 62 NO. 2 (1846) Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) BALLADE NO. 1, IN G MINOR, OP. 23 (c1825) Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) VARIATIONS SÉRIEUSES, OP. 54, MWV U156 (1841) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY STEPHEN PERRY AND OLIVER RADFORD Thank you to our Corporate Sponsor Rockport Music Notes “It would be hard to conceive of anything more amusing than this little escapade. How I laughed when I played it for the first time! And how astonished I was when, a second time through, I read a footnote telling me that this capriccio, discovered among Beethoven's manuscripts after his death, bore the title: "Fury over the Lost Penny, Vented in a Caprice" . Oh! It's the most adorable, futile fury, like that which seizes you when you can't get a boot off, and you sweat and swear and the boot looks up at you, phlegmatically-and unmoved! . -

RONALD BRAUTIGAM Fortepiano FÜR ELISE the Complete Bagatelles

RONALD BRAUTIGAM fortepiano FÜR ELISE The Complete Bagatelles BIS-SACD-1882 BIS-SACD-1882_f-b.indd 1 11-04-19 14.00.40 van BEETHOVEN, Ludwig (1770–1827) Complete Works for Solo Piano – Volume 10 The Complete Bagatelles Sieben Bagatellen, Op. 33 (1802) 18'53 1 1. Andante grazioso, quasi allegretto 3'25 2 2. Scherzo. Allegro 2'42 3 3. Allegretto 2'11 4 4. Andante 2'38 5 5. Allegro, ma non troppo 2'46 6 6. Allegretto, quasi andante (Con una certa espressione parlante) 2'59 7 7. Presto 1'53 Bagatelles 1795–1804 8 Allegretto in C minor, Hess 69 (c.1797) 3'06 9 Bagatelle in C major, Hess 73 (1800) 0'23 10 Bagatelle in E flat major, Hess 74 (1800) 0'20 11 Allegretto in C minor, WoO 53 (1796–98) 3'19 12 Andante in C major (1792–95) 0'59 13 Klavierstück in C major ‘Lustig – traurig’, WoO 54 (c.1798) 1'34 14 Bagatelle in C major, WoO 56 (1803–04) 1'43 15 Bagatelle in C minor, WoO 52 (1795) 3'38 Elf Neue Bagatellen, Op. 119 (1820–22) 13'17 16 1. Allegretto 2'14 17 2. Andante con moto 0'58 18 3. à l’Allemande 1'35 2 19 4. Andante cantabile 1'25 20 5. Risoluto 0'59 21 6. Andante – Allegretto 1'31 22 7. Allegro, ma non troppo 0'50 23 8. Moderato cantabile 1'15 24 9. Vivace moderato 0'37 25 10. Allegramente 0'11 26 11. Andante, ma non troppo 1'17 Bagatelles 1810–25 27 Bagatelle in A minor ‘Für Elise’, WoO 59 (1810) 2'37 28 Klavierstück in B flat major, WoO 60 (1818) 1'07 29 Klavierstück in B minor, WoO 61 (1821) 2'01 30 Klavierstück in G minor, WoO 61a (1825) 0'27 31 Bagatelle in C major, Hess 57 (1823–24) 0'46 Sechs Bagatellen, Op. -

Beethoven.Qxp PH????? Booklet Gamben/Handel 17.06.19 08:51 Seite 1

HC19032.Booklet.16CD.Beethoven.qxp_PH?????_Booklet_Gamben/Handel 17.06.19 08:51 Seite 1 BEETHOVEN Complete Piano Works MARTINO TIRIMO 16 CDs HC19032.Booklet.16CD.Beethoven.qxp_PH?????_Booklet_Gamben/Handel 17.06.19 08:51 Seite 2 BEETHOVEN MARTINO TIRIMO BEETHOVEN Introduction perienced financial difficulties and his third Variation in the second movement of be delighted by them. I, myself, so en- Does Ludwig van Beethoven need any in- romantic relationships were often hampe- his last Sonata Op.111, are amazed at joyed ‘discovering’ the youthful Sonatas troduction? He is, after all, one of the red by the issue of class. Also, perhaps the similarity to the jazz idiom. Whether and other Sonata movements, some en- greatest of the great composers and one only a musician can appreciate fully the the founders of jazz were aware of Beet- chanting Variation sets, some delectable of the most popular. Many of his works loss of the sense of hearing. All these hoven’s astonishing expression is doubtful, Dances and Bagatelles, Preludes and are performed endlessly and audiences experiences deepened his emotional but this is surely the earliest ‘jazzy’ piece Rondos and much else. The whole journey throughout the world flock to concert halls world and sharpened his intellect. They of all! was an education and, if anything, increased to hear them. helped him in his reach for an expression my admiration for this giant of music. most musicians cannot even envisage. Elsewhere, the listener can only marvel at My question is: would he have produced the wealth of invention. Beethoven loved There are a handful of pieces, which may the remarkable number and quality of His piano output alone is enormous and to experiment and it was in his works for or may not be authentic. -

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

DOCUMENTS SUR Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897) (Mise à jour le 17 mai 2013) Médiathèque Musicale Mahler 11 bis, rue Vézelay – F-75008 Paris – (+33) (0)1.53.89.09.10 www.mediathequemahler.org Médiathèque Musicale Mahler – Johannes Brahms Livres et documents sur Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) LIVRES Sur Johannes Brahms 3 Brahms dans les biographies d'autres compositeurs… 9 Brahms dans les ouvrages thématiques… 11 PARTITIONS 17 ENREGISTREMENTS SONORES 22 Brahms dans les disques d'autres compositeurs 69 REVUES 89 ARCHIVES NUMÉRISÉES 89 FONDS D'ARCHIVES 90 2 Médiathèque Musicale Mahler – Johannes Brahms LIVRES SUR JOHANNES BRAHMS Aimez-vous Brahms "the progressive" ?. - München : Text + kritik, 1989. – (BM BRA E2) Brahms / préf. de J.C. Teboul. - Paris : Place, 1997. – (BM BRA E3) Brahms. 2 / préf. de J.C. Teboul. - Paris : Place, 1999. – (BM BRA E4) Johannes Brahms : Leben, Werk, Interpretation, Rezeption : Kongressbericht zumIII. Gewandhaus-Symposium anlässlich der "Gewandhaus-Festtage 1983". - Leipzig : Gewandhaus zu Leipzig, 1983. – (BM BRA D3) Johannes Brahms : les symphonies. - Paris : L'Avant-Scène, 1983. – (BM BRA G Symph Ge) Johannes Brahms : the autograph manuscripts of the clarinet sonatas op. 120 numbers 1 and 2 : auction Friday 5 december 1997..., Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place, London. - London : Sotheby's, 1997. – (BM BRA G Musique de chambre) Thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher im Druck erschienenen Werke von Johannes Brahms. - Berlin : Simrock, 1902. – (BM BRA A1 (Réserve)) Thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher im Druck erschienenen Werke von Johannes Brahms. - Berlin : Simrock, 1904. – (BM BRA A2 (Réserve)) ALLEY Marguerite. - A passionate friendship : Clara Schumann and Brahms / translated by Mervyn Savill. - London : Staples Press, 1956. – (BM BRA B14) ALLEY Marguerite. -

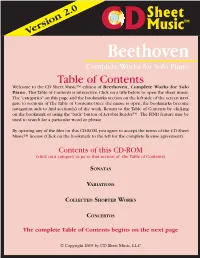

View the Table of Contents

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 Beethoven Complete Works for Solo Piano Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of Beethoven, Complete Works for Solo Piano. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “categories” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navi- gate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Contents of this CD-ROM (click on a category to go to that section of the Table of Contents) SONATAS VARIATIONS COLLECTED SHORTER WORKS CONCERTOS The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 SONATAS Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 2, No. 1 Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Op. 2, No. 2 Sonata No. 3 in C Major, Op. 2, No. 3 Sonata No. 4 in Eb Major, Op. 7 Sonata No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 10, No. 1 Sonata No. 6 in F Major, Op.