Program Notes © 2021 Keith Horner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

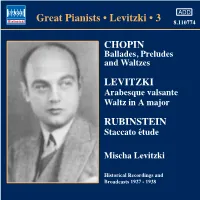

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected]

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2014 A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation Inouye, Michiko, "A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major" (2014). Honors Thesis Collection. 224. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/224 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann’s Phantasie in C Major Michiko O. Inouye Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Wellesley College Music Department April 2014 Copyright 2014 Michiko Inouye Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the wonderful guidance, feedback, and mentorship of Professor Charles Fisk. I am deeply appreciative of his dedication and patience throughout this entire process. I am also indebted to my piano teacher of four years at Wellesley, Professor Lois Shapiro, who has not only helped me grow as a pianist but through her valuable teaching has also led me to many realizations about Op. 111 and the Phantasie, and consequently inspired me to come up with many of the ideas presented in this thesis. Both Professor Fisk and Professor Shapiro have given me the utmost encouragement in facing the daunting task of both writing about and working to perform such immortal pieces as the Phantasie and Op. -

Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words

Friday 04 – Sunday 06 March 2016 RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS WELCOME The RNCM Chamber Music Festival plays an enormous role in the story of the College and is a major event in our calendar. Chamber music is at the core at what we do - the RNCM has a proud tradition of chamber ensemble training and our alumni appear with high profile ensembles such as the Elias, Heath and Navarra String Quartets plus the Gould Piano Trio to name but a few. Every year, the Chamber Music Festival goes from strength to strength, presenting the opportunity to see our wonderful students, internationally renowned staff and special guests perform beautiful music across a jam-packed weekend. This year is no exception, as we explore German Romanticism in Songs Without Words. We focus particularly on the music of Mendelssohn and Schumann and our students will be involved in a major composition project, as they are asked to create responses to Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. So the Festival will include works from across the 19th century but will also dip into the 20th century with composers such as Richard Strauss. This year’s line-up features some of the finest musicians performing today including the Talich Quartet, Elias Quartet, Michelangelo Quartet, plus RNCM Junior Fellows the Solem Quartet and our International Artist chamber ensemble the Diverso String Quartet. We also welcome chamber groups from Chetham’s, St Mary’s, Junior RNCM, the Royal Irish Academy of Music and Sheffield Music Academy. So please join us and immerse yourself in this weekend of lush musical landscapes. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Saison 2021 /22 Saison 2021 /22 Herzlich Willkommen! Alte Oper Frankfurt Inhaltsverzeichnis

SAISON 2021 /22 SAISON 2021 /22 HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN! ALTE OPER FRANKFURT INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Einmal mit den Flügeln INHALT schlagen und abheben bitte. Starten Sie mit uns einen Flug über die Alte Oper, mitten ins IM ÜBERBLICK ABONNEMENTS 19 Herz der Stadt! FESTIVALS UND SCHWERPUNKTE 33 KONGRESSE UND EVENTS 51 DAS OFFENE HAUS 55 DANK 73 DIE KONZERTSAISON 2021/22 DIE KONZERTE DER ALTEN OPER TAG FÜR TAG 81 ANGEBOTE DER PARTNER 161 SERVICE 177 NEUE PERSPEKTIVEN So haben Sie das Konzerthaus noch nie gesehen. Halten Sie einfach die Kamera Ihres Smartphones auf den abgebildeten Code, um die Alte Oper aus ungewohnter Perspektive zu entdecken. Oder gehen Sie auf www.alteoper.de/rundflug 2 3 GELEITWORT ZUM PROGRAMM GELEITWORT ZUM PROGRAMM PETER FELDMANN DR. MARKUS FEIN Oberbürgermeister der Stadt Frankfurt am Main Intendant und Geschäftsführer der Alten Oper Frankfurt Vorsitzender des Aufsichtsrats der Alten Oper Frankfurt Es ist gut, Perspektiven zu haben – nicht nur in Krisenzeiten. Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, Wenn ich das Programm der Alten Oper betrachte, entdecke ich liebe Besucher*innen der Alten Oper, neue Perspektiven in mehrfacher Hinsicht: Es sind einerseits Aus- sichten auf die Rückkehr zur Normalität im Kulturbetrieb. Aber Die Alte Oper ohne Publikum? Das war für uns unvorstellbar, und zugleich zeigen sich andere Blickwinkel. Mich freut, wie sich auch nach Monaten des Lockdowns können und wollen wir uns zahlreiche Projekte auf Frankfurt selbst konzentrieren und in die nicht daran gewöhnen. Zu wichtig ist uns der Dialog mit Ihnen, Stadt hineinwirken. Derzeit sind mehr denn je Zusammenhalt unserem Publikum. Die Alte Oper ist ein Haus, das sich vielfältig und gegenseitiges Verständnis gefordert. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

Beethoven, Bonn and Its Citizens

Beethoven, Bonn and its citizens by Manfred van Rey The beginnings in Bonn If 'musically minded circles' had not formed a citizens' initiative early on to honour the city's most famous son, Bonn would not be proudly and joyfully preparing to celebrate his 250th birthday today. It was in Bonn's Church of St Remigius that Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized on 17 December 1770; it was here that he spent his childhood and youth, received his musical training and published his very first composition at the age of 12. Then the new Archbishop of Cologne, Elector Max Franz from the house of Habsburg, made him a salaried organist in his renowned court chapel in 1784, before dispatching him to Vienna for further studies in 1792. Two years later Bonn, the residential capital of the electoral domain of Cologne, was occupied by French troops. The musical life of its court came to an end, and its court chapel was disbanded. If the Bonn music publisher Nikolaus Simrock (formerly Beethoven’s colleague in the court chapel) had not issued several original editions and a great many reprints of Beethoven's works, and if Beethoven's friend Ferdinand Ries and his father Franz Anton had not performed concerts of his music in Bonn and Cologne, little would have been heard about Beethoven in Bonn even during his lifetime. The first person to familiarise Bonn audiences with Beethoven's music at a high artistic level was Heinrich Karl Breidenstein, the academic music director of Bonn's newly founded Friedrich Wilhelm University. To celebrate the anniversary of his baptism on 17 December 1826, he offered the Bonn première of the Fourth Symphony in his first concert, devoted entirely to Beethoven. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Concerto And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Concerto and Recital Works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Poulenc and Rachmaninoff A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Performance by Peter Shannon May 2016 The graduate project of Peter Shannon is approved: _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Soo-Yeon Chang Date _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Alexandra Monchick Date _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Dmitry Rachmanov, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page ii Abstract iv Section 1: Toccata in F-sharp Minor BWV 910 by J.S. Bach 1 Section 2: Piano Sonata Op. 109 in E major by L.V. Beethoven 4 Section 3: Variations Sérieuses in D minor by Felix Mendelssohn 7 Section 4: Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor by Frédéric Chopin 9 Section 5: Barcarolle in F-sharp major by Frédéric Chopin 10 Section 6: Napoli Suite, FP 40 by Francis Poulenc 13 Section 7: Etude-Tableau Op. 39 no. 9 by Sergei Rachmaninoff 17 Bibliography 20 Appendix A: Program I (Concerto) 21 Appendix B: Program II (Solo Recital) 22 iii Abstract Recital and Concerto Works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Poulenc and Rachmaninoff By Peter Shannon Master of Music in Music, Performance Johann Sebastien Bach (1685-1750) explored the genres and forms of the Baroque period with astonishing complexity and originality. Bach used the form of the toccata to couple the rigorous logic of Baroque counterpoint to the fantastic possibilities of improvisational harmony. The Piano Sonata Op. 109 in E major is the first of the final three piano sonatas by the German composer Ludwig van Beethoven. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music London’s Symphony Orchestra Celebrating LSO Members with 20+ years’ service. Visit lso.co.uk/1617photos for a full list. LSO Season 2016/17 Free concert programme London Symphony Orchestra LSO ST LUKE’S BBC RADIO 3 LUNCHTIME CONCERTS – AUTUMN 2016 MOZART & TCHAIKOVSKY LAWRENCE POWER & FRIENDS Ten musicians explore Tchaikovsky and his The violist is joined by some of his closest musical love of Mozart, through songs, piano trios, collaborators for a series that celebrates the string quartets and solo piano music. instrument as chamber music star, with works by with Pavel Kolesnikov, Sitkovetsky Piano Trio, Brahms, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven and others. Robin Tritschler, Iain Burnside & with Simon Crawford-Phillips, Paul Watkins, Ehnes String Quartet Vilde Frang, Nicolas Altstaedt & Vertavo Quartet For full listings visit lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Monday 19 September 2016 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT Leif Ove Andsnes Beethoven Piano Sonata No 18 (‘The Hunt’) Sibelius Impromptus Op 5 Nos 5 and 6; Rondino Op 68 No 2; Elegiaco Op 76 No 10; Commodo from ‘Kyllikki‘ Op 41; Romance Op 24 No 9 INTERVAL Debussy Estampes Chopin Ballade No 2 in F major; Nocturne in F major; Ballade No 4 in F minor Leif Ove Andsnes piano Concert finishes at approximately 9.25pm 4 Welcome 19 September 2016 Welcome Kathryn McDowell Welcome to this evening’s concert at the Barbican Centre, where the LSO is delighted to welcome back Leif Ove Andsnes to perform a solo recital, and conclude the critically acclaimed LSO Artist Portrait series that he began with us last season. -

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades William Rothstein There is a style of music which may be called natural, because it is not the offspring of science or reflection, but of an inspiration which sets at defiance all the strictness of rules and convention. I mean popular music, and especially that of the peasantry. How many exquisite compositions are born, live and die, among the peasantry, without ever having been dignified by a correct notation, without ever having deigned to be confined within the absolute limits of a distinct and definite theme. The unknown artist who improvises his rustic ballad while watching his flocks, or guiding his ploughshare, and there are such even in countries which would seem the least poetical, will experience great difficulty in retaining and fixing his fugitive fancies. He communicates his ballad to other musicians, children like himself of nature, and these circulate it from hamlet to hamlet, from cot to cot, each modifying it according to the bent of his own individual genius. It is hence that these pastoral songs and romances, so artlessly striking or so deeply touching, are for the most part lost, and rarely exist above a single century in the memory of their rustic composers. Musicians completely formed under the rules of art rarely trouble themselves to collect them. Many even disdain them from very lack of an intelligence sufficiently pure, and a taste sufficiently elevated to admit of their appreciating them. Others are dismayed by the difficulties which they encounter the moment they endeavor to discover that true and original version, which, perhaps, no longer retains its existence even in the mind of its author, and which certainly was never at any time recognised as a definite and invariable type by any one of his numerous interpreters...