All-Saints-Monksilver-Church-Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stags.Co.Uk 01823 256625 | [email protected]

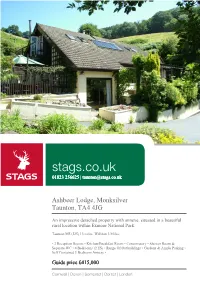

stags.co.uk 01823 256625 | [email protected] Ashbeer Lodge, Monksilver Taunton, TA4 4JG An impressive detached property with annexe, situated in a beautiful rural location within Exmoor National Park. Taunton/M5 (J25) 13 miles. Williton 3 Miles. • 2 Reception Rooms • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Conservatory • Shower Room & Separate WC • 4 Bedrooms (2 ES) • Range Of Outbuildings • Gardens & Ample Parking • Self Contained 1 Bedroom Annexe • Guide price £415,000 Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London Ashbeer Lodge, Monksilver, Taunton, TA4 4JG Situation appointed family home. The accommodation is Ashbeer Lodge occupies a beautiful rural location flexible and gives the ability to utilise rooms for a within the Exmoor National Park. There are variety of uses. It is currently arranged to provide superb views from the property and the a sitting room, dining room, kitchen/breakfast surrounding countryside. The popular village of room, two ground floor bedrooms and two further Monksilver is considered by many to be one of bedrooms on the first floor. the most attractive villages in West Somerset and Accommodation has an ancient church and popular inn. A sitting room with an open fireplace and door Monksilver is located at the foot of the Brendon leads through to the dining room which inturn Hills, just within the Exmoor National Park leads through to the kitchen/breakfast room, boundary. A large range of facilities are available which is fitted with a range of modern units and in the rural town of Williton, which is about three LPG fired Rayburn providing cooking, central miles, and includes stores, supermarkets and heating and hot water. -

West Somerset Railway

How to find us As the Longest Heritage Railway in England Special Events & Days Out 2017 Bridgwater Bay WE ARE MILE FOR MILE BETTER VALUE Burnham- Festive Specials on-Sea J22 With lots of special trains through the festive period, there is something A39 Minehead Steam & Cream Special for everyone - but please pre-book your tickets as these will sell out fast! Porlock A38 WEST SOMERSET Railway Galas Combine your return journey with our Steam and CAROL TRAINS Williton J23 A39 Spring Steam Gala 27th -30th April 2017 Cream Special, where a cream tea will be served Warm up those vocal chords and join us on the 16:30 Minehead to Bishops Lydeard. A396 Diesel Gala & Rail Ale Trail 9th – 11th June 2017 for a special journey of carol singing at Bridgwater 26th March 2017 • 2nd June 2017 • 16th June 2017 Brendon Hills J24 the stations along the way. You will be Exmoor Quantock Late Summer Weekend 2nd – 3rd September 2017 7th July 2017 • 21st July 2017 • 1st September 2017 provided with a carols song book so if you Hills M5 Autumn Steam Gala 5th – 8th October 2017 15th September 2017 Bishops Special Price offered for those combining with don’t know all the words already it doesn’t Dulverton Prices Lydeard A358 TIMETABLE,RAILWAY SPECIAL EVENTS & DAYS OUT GUIDE 2017 Winter Steam Festival 29th – 30th December 2017 matter! Our carol trains are hauled by a Cheese & Cider Special. Taunton heritage steam locomotives to recreate start from J25 the era of Christmas gone by. A38 A358 £245.00 Wellington Dates: 11th and 12th December 2017 J26 Prices: Adult/Senior -

The Old Post Office the Old Post Office Stogumber, Taunton, TA4 3TA Taunton - 14 Miles, Minehead - 12 Miles

The Old Post Office The Old Post Office Stogumber, Taunton, TA4 3TA Taunton - 14 miles, Minehead - 12 miles • Large Open Plan Sitting Room • Separate Fitted Kitchen • 3 Good Sized Bedrooms • Gardens With Wonderful Views • Many Period Features • Fitted Bathroom Suite • Downstairs WC • Popular Village Location Guide price £299,950 Description The Old Post Office is a fine example of a 17th Century, Grade II Listed, village house, which has been through an interesting history and is believed to have once been two cottages. During the 20th Century the cottage was made into one premises and used as the village Post Office. The King George post box is still in the wall of the cottage with post being collected twice a day. The cottage was then turned into a private residence in 1970 A beautifully presented Grade II listed 17th Century, thatched and had one owner for over 30 years. The current owners have fully refurbished the property but have been mindful to retain cottage situated in this highly sought after village. many of the period features, which include two deep inglenook fireplaces, one with a woodburning stove, heavy beamed ceilings and pretty glazed sash windows. Accommodation The accommodation includes an entrance porch, which opens through to a large open plan sitting/dining room. The sitting room area has an inglenook fireplace with inset woodburning stove, beam over and tiled hearth. There are two front aspect sash windows, an arched display recess, fitted cupboard, further storage cupboard, part of the original spiral wooden staircase that used to lead to the first floor and a door to the rear hallway. -

Published by ENPA November 2009 1 EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK

EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK EMPLOYMENT LAND REVIEW Published by ENPA November 2009 1 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 1st Floor, Westville House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0EL Offices also in T 029 2043 5880 London F 029 2049 4081 Manchester Newcastle upon Tyne [email protected] www.nlpplanning.com Contents2 Executive Summary 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 11 Scope of the Study 11 The Implications of Exmoor’s Status as a National Park 13 Methodology 15 Report Structure 18 2.0 Local Context 19 Geographical Context 19 Population 21 Economic Activity 22 Distribution of Employees by Sector 25 Qualifications 28 Deprivation 29 Commuting Patterns 32 Businesses 36 Conclusion 36 3.0 Policy Context 37 Planning Policy Context 37 Economic Policy Context 42 Conclusion 48 4.0 The Current Stock of Employment Space 50 Existing Stock of Employment Floorspace 50 Existing Employment Land Provision 55 Conclusion 61 5.0 Consultation 63 Agent Interviews 63 Stakeholder Consultation 65 Business Consultation 68 Previous Consultation Exercises 73 Conclusion 80 6.0 Qualitative Assessment of Existing Employment Sites 81 Conclusion 90 7.0 The Future Economy of Exmoor National Park 92 Establishing an Economic Strategy 92 Influences upon the Economy 93 Key Sectors 95 1 30562/517407v2 Conclusion 97 8.0 Future Need for Employment Space 99 Employment Growth 99 Employment Based Space Requirements 105 Planning Requirement for Employment Land 112 9.0 The Role of Non-B Class Sectors in the Local Economy 114 Introduction 114 Agriculture 114 Public Sector Services 119 Retail 122 10.0 -

Accents, Dialects and Languages of the Bristol Region

Accents, dialects and languages of the Bristol region A bibliography compiled by Richard Coates, with the collaboration of the late Jeffrey Spittal (in progress) First draft released 27 January 2010 State of 5 January 2015 Introductory note With the exception of standard national resources, this bibliography includes only separate studies, or more inclusive works with a distinct section, devoted to the West of England, defined as the ancient counties of Bristol, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Note that works on place-names are not treated in this bibliography unless they are of special dialectological interest. For a bibliography of place-name studies, see Jeffrey Spittal and John Field, eds (1990) A reader’s guide to the place-names of the United Kingdom. Stamford: Paul Watkins, and annual bibliographies printed in the Journal of the English Place-Name Society and Nomina. Web-links mentioned were last tested in summer 2011. Thanks for information and clarification go to Madge Dresser, Brian Iles, Peter McClure, Frank Palmer, Harry Parkin, Tim Shortis, Jeanine Treffers-Daller, Peter Trudgill, and especially Katharina Oberhofer. Richard Coates University of the West of England, Bristol Academic and serious popular work General English material, and Western material not specific to a particular county Anderson, Peter M. (1987) A structural atlas of the English dialects. London: Croom Helm. Beal, Joan C. (2006) Language and region. London: Routledge (Intertext). ISBN-10: 0415366011, ISBN-13: 978-0415366014. 1 Britten, James, and Robert Holland (1886) A dictionary of English plant-names (3 vols). London: Trübner (for the English Dialect Society). Britton, Derek (1994) The etymology of modern dialect ’en, ‘him’. -

Flood Risk Management Plan

LIT 10224 Flood risk management plan South West river basin district summary March 2016 What are flood risk management plans? Flood risk management plans (FRMPs) explain the risk of flooding from rivers, the sea, surface water, groundwater and reservoirs. FRMPs set out how risk management authorities will work with communities to manage flood and coastal risk over the next 6 years. Risk management authorities include the Environment Agency, local councils, internal drainage boards, Highways Authorities, Highways England and lead local flood authorities (LLFAs). Each EU member country must produce FRMPs as set out in the EU Floods Directive 2007. Each FRMP covers a specific river basin district. There are 11 river basin districts in England and Wales, as defined in the legislation. A river basin district is an area of land covering one or more river catchments. A river catchment is the area of land from which rainfall drains to a specific river. Each river basin district also has a river basin management plan, which looks at how to protect and improve water quality, and use water in a sustainable way. FRMPs and river basin management plans work to a 6- year planning cycle. The current cycle is from 2015 to 2021. We have developed the South West FRMP alongside the South West river basin management plan so that flood defence schemes can provide wider environmental benefits. Both flood risk management and river basin planning form an important part of a collaborative and integrated approach to catchment planning for water. Building on this essential work, and in the context of the Governments 25-year environment plan, we aim to move towards more integrated planning for the environment over the next cycle. -

Minutes of the Meeting of STOGUMBER PARISH COUNCIL

Stogumber Parish Council. Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held in Deane Close Common Room on 12th January 2017 The meeting started at 19:50 Present J. Spicer (Chairman), M Symes, T Vesey, C Bramall, C Matravers, J Hull, T Brick , V Sellick C Morrison-Jones, Clerk C Lawrence (County Councillor), A Trollope-Bellew (District Councillor) Item Topic. 1. Apologies G Tuckfield 2. Declarations of Interest and requests for Dispensations. M Symes and T Vesey (Village Signs, financial contribution, item 17) 3. Public comments, questions or suggestions. There were no public comments, questions or suggestions made. 4. Minutes It was resolved that the draft minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on 10/11/16 plus planning meetings held on 23/11 & 17/12/16 were a true and correct record of the meetings. 5. Matters Arising from the minutes None 6. County Councillor Report Williton and Minehead hospitals: Cllr Christine Lawrence reported that she had met with the clinical commissioning group to ascertain the Williton & Minehead hospitals situation. Wards in Minehead had been closed, due to lack of staff, and patients moved to Williton which is now full. The real problem is due to difficulties in recruiting staff, not finance, and this brings with it grave concerns as the area has a high proportion of elderly residents. Further talks are planned for two weeks’ time with the partnership board regarding training and the need to encourage young people to train and remain in the area once qualified. Buses: the Porlock to Minehead service has been kept running for the present. -

Coleridge Bridle

Coleridge Bridle Way 15 ST 073 374 MONKSILVER With the Notley Arms and church on your R take next road R, where main road bears left, and after 50 yards take bridleway on L signed to A horse riding route from the Quantock Hills to Exmoor Colton Cross. Continue up Bird’s Hill bridleway for around one mile to 33 Miles from Nether Stowey to Exford road at Colton Cross. 2. The Brendon Hills 16 ST 057 362 Ride along road directly opposite. After around 400 yards, look out for MONKSILVER TO LUXBOROUGH a gate on the R signposted to Sticklepath. Go through gate and go directly across field to the corner of the wood ahead and with woodland General Description on your R carry on to gate. Go through gate into woodland and follow A challenging section with some steep climbs and descents blue waymarked bridleway straight ahead, ignoring all paths off left and and a large number of gates, with some stock in fields. right, down hill. Near the bottom take L hand fork uphill signed to Ralegh’s Cross. Between Windwhistle Farm and Lype Hill the route may go alongside shoots at certain times of year. 17 ST 047 361 A one mile climb up Bird’s Hill (soft sunken lane) from After a short distance you pass through a gate and continue on track. Monksilver. Steady down hill and then steady uphill on soft When you reach an open field go through gate on L and follow track woodland tracks and across grassy fields to Ralegh’s Cross. -

Flooding in West Somerset: Overview of Local Risks and Ideas for Action

FLOODING IN WEST SOMERSET: OVERVIEW OF LOCAL RISKS AND IDEAS FOR ACTION A discussion document by the West Somerset Flood Group June 2014 The West Somerset Flood Group WHO WE ARE We are a group of town and parish councils (and one flood group) actively working to reduce flood risk at local level. We have come together because we believe that the communities of West Somerset should have a voice in the current debate on managing future flood risk. We also see a benefit in providing a local forum for discussion and hope to include experts, local- authority officers and local landowners in our future activities. We are not experts on statutory duties, powers and funding, on the workings of local and national government or on climate change. We do, however, know a lot about the practicalities of working to protect our communities, we talk to both local people and experts, and we are aware of areas where current structures of responsibility and funding may not be working smoothly. We also have ideas for future action against flooding. We are directly helped in our work by the Environment Agency, Somerset County Council (Flood and Water Management team, Highways Department and Civil Contingencies Unit), West Somerset Council, Exmoor National Park Authority and the National Trust and are grateful for the support they give us. We also thank our County and District Councillors for listening to us and providing support and advice. Members: River Aller and Horner Water Community Flood Group, Dulverton TC, Minehead TC, Monksilver PC, Nettlecombe PC, Old Cleeve PC, Porlock PC, Stogursey PC, Williton PC For information please contact: Dr T Bridgeman, Rose Villa, Roadwater, Watchet, TA23 0QY, 01984 640996 [email protected] Front cover photograph: debris against Dulverton bridge over the River Barle (December 23 2012). -

Williton Parish Council

Welcome to Williton Parish Council. The Parish of Williton covers Williton and the villages of Doniford, Egrove, Stream, parts of Five Bells and to the outskirts of Washford, Samford Brett, Watchet, Monksilver and West Quantoxhead. Williton is a Village and has been the administrative centre for the District of West Somerset since 1974. Williton is situated at the junction of the A39 and the A358. It is almost equidistant between Minehead, Bridgwater and Taunton. Williton Parish has two railway stations, Williton station and Doniford Halt which serves the nearby Haven Holiday centre. The stations form part of the West Somerset Railway who operate services using both heritage steam and diesel trains. Doniford has a popular beach accessed via a car park and ramp which the Parish rent for the Community to use. Williton Parish Council comprises of up to twelve elected members from our Community which are unpaid for their work, (Parish Councillors) we administer the Parish for the community. The Parish Council also employs two Clerks to facilitate this process. Williton Parish Council act as the Trustee of the Williton War Memorial Recreation Ground. This involves the day to day maintenance of the field. Including contracting groundworks, grass cutting, shrub/hedge maintenance and to maintain the play equipment. The Parish Council also maintain the War Memorial. Recently the Parish have installed CCTV on the Recreation Ground to improve security for all users. The Parish Council hold regular events on the Recreation Ground including Duck Racing and the Village Fete. The Parish Council leases land for the Community at: • Doniford , where we maintain the car park for the beach • The Copse , near Saint Peters Church, which the Parish Council have planted with some trees and is popular with dog owners • Bellamy’s Corner (corner of High Street and Bank Street) which is maintained as an open space with picnic tables for all to use. -

Musgrove Park Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

COUNCIL OF GOVERNORS’ QUALITY AND PATIENT EXPERIENCE GROUP Wednesday 4 November 2020, 2.00 – 4.00 pm Microsoft Teams Agenda 14:00 1. Welcome and apologies: Verbal Apologies have been received from Neil Thomas 2. Draft minutes of the meeting held on 4 August 2020 Enc A 3. Review of the action log and matters arising Enc B 4. To ratify the appointment of: JG Enc C Vice-Chairman Mental Health Act Committee representative FOR DISCUSSION 14:15 5. Patient and Public Involvement Manager’s Report HH Enc D – To follow Complaints and PALS Manager report Recent national survey results Patient section of the Performance Report Enc E 14.45 6. Raising Awareness of Suicide Prevention and AVL Enc F Presentation Mental Health Transformation Update Enc F1 Report In attendance: Alison Van Laar, associate director of mental health and learning disability care 15:15 7. QPI Review 2020/21 ST Verbal KPI Setting 2021/22 15:20 8. Workplan Review and Meeting Dates for 2021 All Enc G FOR INFORMATION 15:25 9. Community support for families/children – The Big Report Enc H Tent 10. Good to Know Log JG Enc I 11. Feedback from the Quality and Governance JG Enc J Committee 12. Feedback from the Mental Health Act Committee PB Enc K 13. Report from the Signage and Wayfaring Committee KB Enc L 14. Carers and Triangle of Care Report HH Enc M – To Follow 15. Any communication issues arising out of items on All Verbal the agenda 16. Future agenda items All Verbal 17. AOB JG Verbal The chair should be advised of any matters to be raised under Any Other Business in advance of the meeting. -

Changes to Your Waste Collections – Sort It Plus

WS BIN Somerset Waste Partnership Monmouth House, Blackbrook Park Avenue Taunton, Somerset TA1 2PX www.somersetwaste.gov.uk E-mail: [email protected] CHANGES TO YOUR WASTE COLLECTIONS – SORT IT PLUS In October 2011, new Sort It Plus collections for your domestic waste will be introduced. A FORM is enclosed if you wish to request the following changes to the The new services will involve: standard service provided: Weekly recycling collections for paper, A different sized refuse bin (see p.2); cardboard, glass, plastic bottles, cans, foil, A recycling box if you have not got one clothes, shoes and car batteries; or your current one is damaged; Weekly collections of food waste; Arrange a new assisted collection. Fortnightly collections for refuse; To make a request, please return the Optional (charged) fortnightly collections for enclosed form by 7th September 2011 garden waste. These collections already work very successfully in other Somerset districts. They have proved to be very popular and make a big difference. Sort It Plus leads to twice as much waste being recycled and halves the amount of rubbish sent to landfill. This benefits our environment by conserving resources, saving energy and reducing carbon emissions. It also avoids rising costs of waste disposal, as landfill now costs over £75 per tonne and will increase to over £100 per tonne in 2014. For the new collections, we will provide: A kitchen caddy and small bin for food waste; A second recycling box; If your property is suitable, a wheeled bin for your refuse. Garden waste will not be accepted with refuse collections for disposal.