Kingcome Village's Estuarine Gardens As Contested Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

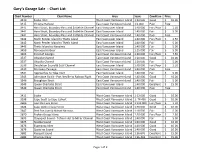

Gary's Charts

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

A Nitrogen Budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with Emphasis on Particulate Nitrogen and Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen

Biogeosciences, 10, 7179–7194, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7179/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7179-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. A nitrogen budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with emphasis on particulate nitrogen and dissolved inorganic nitrogen J. N. Sutton1,2, S. C. Johannessen1, and R. W. Macdonald1 1Institute of Ocean Sciences, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 9860 West Saanich Road, P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, British Columbia, V8L 4B2, Canada 2Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, California, 94720, USA Correspondence to: J. N. Sutton ([email protected]) Received: 6 March 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 23 April 2013 Revised: 29 September 2013 – Accepted: 10 October 2013 – Published: 12 November 2013 Abstract. Balanced budgets for dissolved inorganic N (DIN) 1 Introduction and particulate N (PN) were constructed for the Strait of Georgia (SoG), a semi-enclosed coastal sea off the west coast of British Columbia, Canada. The dominant control on the The nitrogen (N) cycle is a crucial underpinning of marine N budget is the advection of DIN into and out of the SoG biological productivity (Gruber and Galloway, 2008). Dur- via Haro Strait. The annual influx of DIN by advection from ing the past 150 yr, the global N cycle has been dramati- the Pacific Ocean is 29 990 (±19 500) Mmol yr−1. The DIN cally changed by human activities that have loaded reactive N flux advected out of the SoG is 24 300 (±15 500) Mmol yr−1. into ecosystems in amounts that rival natural sources (Rabal- Most of the DIN that enters the SoG (∼ 23 400 Mmol yr−1) ais, 2002; Galloway et al., 2004). -

Reduced Annualreport1972.Pdf

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND CONSERVATION HON. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS, Minister LLOYD BROOKS, Deputy Minister REPORT OF THE Department of Recreation and Conservation containing the reports of the GENERAL ADMINISTRATION, FISH AND WILDLIFE BRANCH, PROVINCIAL PARKS BRANCH, BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL MUSEUM, AND COMMERCIAL FISHERIES BRANCH Year Ended December 31 1972 Printed by K. M. MACDONALD, Printer to tbe Queen's Most Excellent Majesty in right of the Province of British Columbia. 1973 \ VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 To Colonel the Honourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., O.B.E., Q.C., LLD., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: Herewith I beg respectfully to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS Minister of Recreation and Conservation 1_) VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 The Honourable Robert A. Williams, Minister of Recreation and Conservation. SIR: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. LLOYD BROOKS Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation CONTENTS PAGE Introduction by the Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation_____________ 7 General Administration_________________________________________________ __ ___________ _____ 9 Fish and Wildlife Branch____________ ___________________ ________________________ _____________________ 13 Provincial Parks Branch________ ______________________________________________ -

PROVINCI L Li L MUSEUM

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCI_l_Li_L MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY • FOR THE YEAR 1930 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to tbe King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1931. \ . To His Honour JAMES ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Administrator of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1930. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Pt·ovincial Secretary. Pt·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.O., March 26th, 1931. PROVINCIAl. MUSEUM OF NATURAl. HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 26th, 1931. The Ho1Wm·able S. L. Ho11ie, ProvinciaZ Secreta11}, Victo1·ia, B.a. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1930, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE. Staff of the Museum ............................. ------------ --- ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------- 6 Object.. .......... ------------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------------- -- ---------- -- ------------------------ ----- ------------------- 7 Admission .... ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Tissue Variability in the Infaunal Bivalve Axinopsida Serricata

Tissue variability in the infaunal bivalve Axinopsida serricata (Lucinacea: Thyasiridae) exposed to a marine mine-tailings discharge; and associated population effects. Douglas Arthur Bright Bachelor of Science, University of Victoria, 1984 Master of Science, University of Victoria, 1987 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY A L L h r J. L IJ jn Department FACULTY OF bRADUATY STUDIlib ofBiology ------------------ •<“— '— We accept this thesis as conforming jCffi} - 03— &zjL t0 recluirec^ standard 1 Dr." OV* M is Dr_A.R. Fontaine ' Dr. V.I^Tunnicliffe Dr. A. McAuley Dr. E. Vander Flier-Keller Dr. N. F. Bourne ©Doug A. Bright, 1991 UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA January, 1991 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. 11 Supervisor: Dr. D.V Ellis ABSTRACT Axinopsida serricata (Bivalvia) is abundant in coastal waters of British Columbia subjected to natural and anthropogenic disturbance. To investigate the monitoring potential of histological lesions, field populations were sampled in Holberg Inlet and Quatsino Sound, British Columbia, from benthic habitats affected by the submarine discharge of copper-mine tailings, and from a reference site in Mill Bay, Saanich Inlet. Based on a quantitative analysis of the digestive gland, ctenidia, kidney, gonad and stomach, the relationship between histological variation and site, size, season, sex and parasitism was explored. The relationship between occurrence of histological lesions in this species and further ecological consequences of mine- tailings discharge was also explored by comparing population characteristics of clams living in deposited tailings with clams from the reference site. -

Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Region of British Columbia

MARINE RECREATION IN THE DESOLATION SOUND REGION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA by William Harold Wolferstan B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography @ WILLIAM HAROLD WOLFERSTAN 1971 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December, 1971 Name : William Harold Wolf erstan Degree : Master of Arts Title of Thesis : Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Area of British Columbia Examining Committee : Chairman : Mar tin C . Kellman Frank F . Cunningham1 Senior Supervisor Robert Ahrens Director, Parks Planning Branch Department of Recreation and Conservation, British .Columbia ABSTRACT The increase of recreation boating along the British Columbia coast is straining the relationship between the boater and his environment. This thesis describes the nature of this increase, incorporating those qualities of the marine environment which either contribute to or detract from the recreational boating experience. A questionnaire was used to determine the interests and activities of boaters in the Desolation Sound region. From the responses, two major dichotomies became apparent: the relationship between the most frequented areas to those considered the most attractive and the desire for natural wilderness environments as opposed to artificial, service- facility ones. This thesis will also show that the most valued areas are those F- which are the least disturbed. Consequently, future planning must protect the natural environment. Any development, that fails to consider the long term interests of the boater and other resource users, should be curtailed in those areas of greatest recreation value. iii EASY WILDERNESS . Many of us wish we could do it, this 'retreat to nature'. -

Flea Village—1

Context: 18th-century history, west coast of Canada Citation: Doe, N.A., Flea Village—1. Introduction, SILT 17-1, 2016. <www.nickdoe.ca/pdfs/Webp561.pdf>. Accessed 2016 Nov. 06. NOTE: Adjust the accessed date as needed. Notes: Most of this paper was completed in April 2007 with the intention of publishing it in the journal SHALE. It was however never published at that time, and further research was done in September 2007, but practically none after that. It was prepared for publication here in November 2016, with very little added to the old manuscripts. It may therefore be out-of-date in some respects. It is 1 of a series of 10 articles and is the final version, previously posted as Draft 1.5. Copyright restrictions: Copyright © 2016. Not for commercial use without permission. Date posted: November 9, 2016. Author: Nick Doe, 1787 El Verano Drive, Gabriola, BC, Canada V0R 1X6 Phone: 250-247-7858 E-mail: [email protected] Into the labyrinth…. Two expeditions, one led by Captain Vancouver and the other led by Comandante Galiano, arrived at Kinghorn Island in Desolation Sound from the south on June 25, 1792. Their mission was to survey the mainland coast for a passage to the east—a northwest passage. At this stage of their work, they had no idea what lay before them as the insularity of Vancouver Island had yet to be established by Europeans. The following day, all four vessels moved up the Lewis Channel and found a better anchorage in the Teakerne Arm. For seventeen days, small-boat expeditions set out from this safe anchorage to explore the Homfray Channel, Toba Inlet, Pryce Channel, Bute Inlet, and the narrow passages leading westward through which the sea flowed back and forth with astounding velocity. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 W Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug

Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 w Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug. 1995 July 2005 Port Townsend 25,000 47 w Puget Sound – Point No Point to Alki Point 50,000 Mar. 1996 Sept. 2003 Everett 12,500 48 w Puget Sound – Alki Point to Point Defi ance 50,000 Dec. 1995 Aug. 2011 A Tacoma 15,000 B Continuation of A 15,000 50 w Puget Sound – Seattle Harbor 10,000 Mar. 1995 June 2001 Q1 Continuation of Duwamish Waterway 10,000 51 w Puget Sound – Point Defi ance to Olympia 80,000 Mar. 1998 - A Budd Inlet 20,000 B Olympia (continuation of A) 20,000 80 w Rosario Strait 50,000 Mar. 1995 June 2011 1717w Ports in Juan de Fuca Strait - July 1993 July 2007 Neah Bay 10,000 Port Angeles 10,000 1947w Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound 139,000 Oct. 1893 Sept. 2003 2531w Cape Mendocino to Vancouver Island 1,020,000 Apr. 1884 June 1978 2940w Cape Disappointment to Cape Flattery 200,000 Apr. 1948 Feb. 2003 3125w Grays Harbor 40,000 July 1949 Aug. 1998 A Continuation of Chehalis River 40,000 4920w Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 Mar. 2005 - 4921w Queen Charlotte Sound to / à Dixon Entrance 525,000 Oct. 2008 - 4922w Vancouver Island / Île de Vancouver-Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Queen 525,000 Mar. 2005 - Charlotte Sound 4923w Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 Mar. -

The British Columbia Coast 1967

SHRIMP EXPLORATION ON THE BRITISH COLUMBIA COAST 1967 BY M.S.SMITH AND T.H.BUTLER FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION , NANAIMO B.C. CIRCULAR NO.85 FEBRUARY 1968 ~ < SHRIMP EXPLORATION ON THE BRITISH COLUMBIA COAST 1967 BY M.S.SMITH AND T.H.BUTLER FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION , NANAI MO B.C. CIRCULAR NO.85 FEBRUARY 1968 INTRODUCTION The Fisheries Research Board of Canada, with the aid of funds provided by the Industrial Development Service of the Department of Fisheries, con- f . tinued to carry out exploration for new shrimp grounds in 1967. Two observers ^ from the Biological Station at Nanaimo, British Columbia, were aboard a ^ . chartered vessel from July 4 to September 9, 1967. The objective of the survey was to find concentrations of shrimp on the outer continental shelf of British Columbia. The programme, consisted of studying areas considered to have commercial potential and re-assessing the potential of grounds found in past shrimp explorations. VESSEL AND EXTENT OF SURVEY The commercial trawler M.V. Ocean Traveller, under Captain Frank Gale, was chartered to carry out the programme. The vessel is a conventional wooden-hulled combination vessel of 80 gross tons (63 ft keel length) powered by a 220 hp diesel engine. Deck equipment included a hydraulic powered combination seine-trawl winch and a hydraulic net reel, conven tionally rigged for double gear trawling* Each winch drum carried approximately 400 fathoms of 9/16" galvanized wire. Auxiliary equipment included an Ekolite 9B sounder, radar, loran and radios. (This was the same captain and vessel that conducted the Industrial Development Service exploratory groundfish surveys in.1965 and 1966). -

Department Of· Fisheries of Canada Vancouver, B. C

DEPARTMENT OF· FISHERIES OF CANADA VANCOUVER, B. C. 1968 This booklet lists the names and shows the locat·ions of all main stem salmon spawning streams in British Columbia, exclusive of those streams draining through Southeastern Alaska. Not all tributary streams have been included in the listing. I I This material represents a portion of the information being . ' collected for the preparation of an inventory of salmon bearing streams in the Pacific Region. PREPARED BY RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT BRANCH IN COLLABORATION ·WITH CONSERVATION & PROTECTION BRANCH Edited by C. E. Walker DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA PACIFIC AREA MAP SHOWING PROTECTION DISTRICTS AND STATISTICAL ,l\.REAS '- ·-" " . ~--L~-t--?.>~1> ,j '\ "·, -;:.~ '-, ~ .., -" '.) \ 'Uppe_r Arrow Loire \ ) \ ' ('ZC:t;I ;-Koafenoy ;:Lower (!~ LoJ<e Cranb~~"\ \Arrow ',\ ·• ·~ ·\. 1 i 1.AP NU. P. DIS1 • STA'rI3TICAL lAREAS LOCA'rION ..... ··-· ..... -~ ...... ... ~- ............... .. - . ................. ~ .. - ····-·~ --· ·---' --~ .. -'•··--·--·---- .. ·--""'· .. ..._..-~ ...-- ....... ..~---·-··-.-·- ... ---·· l 1 Sub-~District Cari boo ') 1 Sub-District Prince GeorGe ') .) 1 3ub-·-DJ.strict Kamloops.--Lj_llooet· 2 ~issioti-Harrison: Chilli.'wa ck--HoyJe Lower Fraser River ~~ 28 & 29 Howe Sound: New Jestminster 6 3 17, 18, 19 & 20 Nanaimo, Duncan, Victoria c.: 'Port San Juan 7 3 l~· Comox 8 3 15 Toba Inlet (~estview) () ,/ 3 16 Pender Harbour 10 Li- 22 & 23 Nitinat & Barkley Sound 11 Li- 24 Clayoquot Sound 12 l+ 25 Nootka Sound 13 l+ 26 Kyuquot Sound 14 5 J.l Seymour - Belize 15 5 12 Alert Bay (Broughton) 16 5 12 Alert Bay (Knight Inlet) , 1 ..... 17 5 --J Campbell River .., () ..L ~) 5 27 Quatsino Sound 6 9 &·10 Rivers Inlet & Smith Inlet ,..., ,.. 20 ( 0 Butedale (Fraser I\each) 21 '7 6 Butedale (Ki tima t Ar::.1) ') ') l.-t·- '7 7 Bella Bella r'"J ( 8 Bella Coola 8 3 Nass .. -

Oceanographic and Environmental Conditions in the Discovery Islands, British Columbia

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2017/071 National Capital Region Oceanographic and environmental conditions in the Discovery Islands, British Columbia P.C. Chandler1, M.G.G. Foreman1, M. Ouellet2, C. Mimeault3, and J. Wade3 1Fisheries and Oceans Canada Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 West Saanich Road Sidney, British Columbia, V8L 5T5 2Fisheries and Oceans Canada Marine Environmental Data Section, Ocean Science Branch 200 Kent Street Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0E6 3Fisheries and Oceans Canada Aquaculture, Biotechnology and Aquatic Animal Health Science Branch 200 Kent Street Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0E6 December 2017 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2017 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Chandler, P.C., Foreman, M.G.G., Ouellet, M., Mimeault, C., and Wade, J. 2017. Oceanographic and environmental conditions in the Discovery Islands, British Columbia. DFO Can. Sci. Advis.