S41598 018 19779 Z.Pdf (3.656Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting the Concept of Host Range of Plant Pathogens

PY57CH04_Morris ARjats.cls July 18, 2019 12:43 Annual Review of Phytopathology Revisiting the Concept of Host Range of Plant Pathogens Cindy E. Morris and Benoît Moury Pathologie Végétale, INRA, 84140, Montfavet, France; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019. 57:63–90 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on evolutionary history, network analysis, cophylogeny, host jump, host May 13, 2019 specialization, generalism The Annual Review of Phytopathology is online at phyto.annualreviews.org Abstract https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718- Strategies to manage plant disease—from use of resistant varieties to crop 100034 rotation, elimination of reservoirs, landscape planning, surveillance, quar- Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019.57:63-90. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. antine, risk modeling, and anticipation of disease emergences—all rely on All rights reserved knowledge of pathogen host range. However, awareness of the multitude of Access provided by b-on: Universidade de Lisboa (ULisboa) on 09/02/19. For personal use only. factors that influence the outcome of plant–microorganism interactions, the spatial and temporal dynamics of these factors, and the diversity of any given pathogen makes it increasingly challenging to define simple, all-purpose rules to circumscribe the host range of a pathogen. For bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, and viruses, we illustrate that host range is often an overlapping continuum—more so than the separation of discrete pathotypes—and that host jumps are common. By setting the mechanisms of plant–pathogen in- teractions into the scales of contemporary land use and Earth history, we propose a framework to assess the frontiers of host range for practical appli- cations and research on pathogen evolution. -

Puccinia Striiformis in Australia

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Molecular and Host Specificity studies in Puccinia striiformis in Australia By Jordan Bailey A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sydney Plant Breeding Institute May 2013 Statement of Authorship This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university, and to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by any other person, except where references are made in text Jordan Bailey i Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Cooperative Research Centre for National Plant Biosecurity for supporting this project and myself. -

A Survey of Trunk Disease Pathogens Within Citrus Trees in Iran

plants Article A Survey of Trunk Disease Pathogens within Citrus Trees in Iran Nahid Espargham 1, Hamid Mohammadi 1,* and David Gramaje 2,* 1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman 7616914111, Iran; [email protected] 2 Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y del Vino (ICVV), Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Universidad de la Rioja, Gobierno de La Rioja, 26007 Logroño, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.M.); [email protected] (D.G.); Tel.: +98-34-3132-2682 (H.M.); +34-94-1899-4980 (D.G.) Received: 4 May 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: Citrus trees with cankers and dieback symptoms were observed in Bushehr (Bushehr province, Iran). Isolations were made from diseased cankers and branches. Recovered fungal isolates were identified using cultural and morphological characteristics, as well as comparisons of DNA sequence data of the nuclear ribosomal DNA-internal transcribed spacer region, translation elongation factor 1α, β-tubulin, and actin gene regions. Dothiorella viticola, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Neoscytalidium hyalinum, Phaeoacremonium (P.) parasiticum, P. italicum, P. iranianum, P. rubrigenum, P. minimum, P. croatiense, P. fraxinopensylvanicum, Phaeoacremonium sp., Cadophora luteo-olivacea, Biscogniauxia (B.) mediterranea, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, C. boninense, Peyronellaea (Pa.) pinodella, Stilbocrea (S.) walteri, and several isolates of Phoma, Pestalotiopsis, and Fusarium species were obtained from diseased trees. The pathogenicity tests were conducted by artificial inoculation of excised shoots of healthy acid lime trees (Citrus aurantifolia) under controlled conditions. Lasiodiplodia theobromae was the most virulent and caused the longest lesions within 40 days of inoculation. According to literature reviews, this is the first report of L. -

A Survey of Trunk Disease Pathogens Within Citrus Trees in Iran

plants Article A Survey of Trunk Disease Pathogens within Citrus Trees in Iran Nahid Esparham 1, Hamid Mohammadi 1,* and David Gramaje 2,* 1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman 7616914111, Iran; [email protected] 2 Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y del Vino (ICVV), Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Universidad de la Rioja, Gobierno de La Rioja, 26007 Logroño, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.M.); [email protected] (D.G.); Tel.: +98-34-3132-2682 (H.M.); +34-94-1899-4980 (D.G.) Received: 4 May 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: Citrus trees with cankers and dieback symptoms were observed in Bushehr (Bushehr province, Iran). Isolations were made from diseased cankers and branches. Recovered fungal isolates were identified using cultural and morphological characteristics, as well as comparisons of DNA sequence data of the nuclear ribosomal DNA-internal transcribed spacer region, translation elongation factor 1α, β-tubulin, and actin gene regions. Dothiorella viticola, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Neoscytalidium hyalinum, Phaeoacremonium (P.) parasiticum, P. italicum, P. iranianum, P. rubrigenum, P. minimum, P. croatiense, P. fraxinopensylvanicum, Phaeoacremonium sp., Cadophora luteo-olivacea, Biscogniauxia (B.) mediterranea, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, C. boninense, Peyronellaea (Pa.) pinodella, Stilbocrea (S.) walteri, and several isolates of Phoma, Pestalotiopsis, and Fusarium species were obtained from diseased trees. The pathogenicity tests were conducted by artificial inoculation of excised shoots of healthy acid lime trees (Citrus aurantifolia) under controlled conditions. Lasiodiplodia theobromae was the most virulent and caused the longest lesions within 40 days of inoculation. According to literature reviews, this is the first report of L. -

![[Puccinia Striiformis F. Sp. Tritici] on Wheat](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7640/puccinia-striiformis-f-sp-tritici-on-wheat-1467640.webp)

[Puccinia Striiformis F. Sp. Tritici] on Wheat

314 Review / Synthèse Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici ] on wheat X.M. Chen Abstract: Stripe rust of wheat, caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, is one of the most important diseases of wheat worldwide. This review presents basic and recent information on the epidemiology of stripe rust, changes in pathogen virulence and population structure, and movement of the pathogen in the United States and around the world. The impact and causes of recent epidemics in the United States and other countries are discussed. Research on plant resistance to disease, including types of resistance, genes, and molecular markers, and on the use of fungicides are summarized, and strategies for more effective control of the disease are discussed. Key words: disease control, epidemiology, formae speciales, races, Puccinia striiformis, resistance, stripe rust, wheat, yellow rust. Résumé : Mondialement, la rouille jaune du blé, causée par le Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, est une des plus importantes maladies du blé. La présente synthèse contient des informations générales et récentes sur l’épidémiologie de la rouille jaune, sur les changements dans la virulence de l’agent pathogène et dans la structure de la population et sur les déplacements de l’agent pathogène aux États-Unis et autour de la planète. L’impact et les causes des dernières épidémies qui ont sévi aux États-Unis et ailleurs sont examinés. La synthèse contient un résumé de la recherche sur la résistance des plantes à la maladie, y compris les types de résistance, les gènes et les marqueurs moléculaires, et sur l’emploi des fongicides, et un examen des stratégies pour une lutte plus efficace contre la maladie. -

A New Species of Melampsora Rust on Salix Elbursensis from Iran

For. Path. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2010.00699.x Ó 2010 Blackwell Verlag GmbH A new species of Melampsora rust on Salix elbursensis from Iran By S. M. Damadi1,5, M. H. Pei2, J. A. Smith3 and M. Abbasi4 1Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Maragheh, Maragheh, Iran; 2Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, UK; 3School of Forest Resources and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA; 4Plant Pests & Diseases Research Institute, Tehran, Iran; 5E-mail: [email protected] (for correspondence) Summary A rust fungus was found causing stem cankers on 1- to 5-year-old stems of Salix elbursensis in the north west of Iran. The rust also forms uredinia on leaves and flowers of the host willow. Light and scanning electron microscopy revealed that the new rust is morphologically distinct from several Melampsora species occurring on the willows taxonomically close to S. elbursensis, but indistinguish- able from Melampsora larici-epitea. Examination of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal DNA suggested that the rust fungus is phylogenetically close to Melampsora allii-populina and Melampsora pruinosae on Populus spp. Based on both the morphological characteristics and the ITS sequence data, the rust is described as a new species – Melampsora iranica sp. nov. 1 Introduction The genus Melampsora was established by Castagne in 1843 based on the rust on Euphorbia, Melampsora euphorbiae (Schub.) Cast. (Castagne 1843). The main character- istic of the genus Melampsora is the formation of ÔnakedÕ uredinia and crust-like telia that comprise sessile, laterally adherent single-celled teliospores. Of some 80 Melampsora spp. -

Insights to Plant–Microbe Interactions Provide Opportunities to Improve Resistance Breeding Against Root Diseases in Grain Legumes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Organic Eprints Received: 31 December 2017 Revised: 26 March 2018 Accepted: 27 March 2018 DOI: 10.1111/pce.13214 REVIEW Insights to plant–microbe interactions provide opportunities to improve resistance breeding against root diseases in grain legumes Lukas Wille1,2 | Monika M. Messmer1 | Bruno Studer2 | Pierre Hohmann1 1 Department of Crop Sciences, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), 5070 Abstract Frick, Switzerland Root and foot diseases severely impede grain legume cultivation worldwide. Breeding 2 Molecular Plant Breeding, Institute of lines with resistance against individual pathogens exist, but these resistances are Agricultural Sciences, ETH Zürich, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland often overcome by the interaction of multiple pathogens in field situations. Novel Correspondence tools allow to decipher plant–microbiome interactions in unprecedented detail and Pierre Hohmann, Department of Crop provide insights into resistance mechanisms that consider both simultaneous attacks Sciences, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), 5070 Frick, Switzerland. of various pathogens and the interplay with beneficial microbes. Although it has Email: [email protected] become clear that plant‐associated microbes play a key role in plant health, a system- atic picture of how and to what extent plants can shape their own detrimental or Funding information Project “resPEAct”, World Food System Cen- beneficial microbiome remains to be drawn. There is increasing evidence for the exis- ter and Mercator Foundation Switzerland; tence of genetic variation in the regulation of plant–microbe interactions that can be Project LIVESEED, Horizon 2020 Societal Challenges, Grant/Award Number: 727230; exploited by plant breeders. -

Bioinformatic Analysis Deciphers the Molecular Toolbox in the Endophytic/Pathogenic 2 Behavior in F

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.23.436347; this version posted March 23, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Bioinformatic analysis deciphers the molecular toolbox in the endophytic/pathogenic 2 behavior in F. oxysporum f. sp. vanillae - V. planifolia Jacks interaction. 3 Solano De la Cruz MT1**, Escobar – Hernández EE2**, Arciniega – González JA3, Rueda 4 – Zozaya RP1, Adame – García J4, Luna – Rodríguez M5 5 ** These authors contributed equally to this work. 6 1Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito Exterior S/N 7 anexo, Jardín Botánico exterior, Ciudad Universitaria, Ciudad de México, México. 8 2Unidad de Genómica Avanzada, Langebio, Cinvestav, Km 9.6 Libramiento Norte 9 Carretera León 36821, Irapuato, Guanajuato, México. 10 3Centro de Ciencias de la Complejidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 11 Ciudad de México, México. 12 4Tecnológico Nacional de México, Instituto Tecnológico de Úrsulo Galván, Úrsulo Galván, 13 Veracruz, México. 14 5Laboratorio de Genética e Interacciones Planta Microorganismos, Facultad de Ciencias 15 Agrícolas, Universidad Veracruzana. Circuito Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán s/n, Zona 16 Universitaria, Xalapa, Veracruz, México. 17 Abstract 18 Background: 19 F. oxysporum as a species complex (FOSC) possesses the capacity to specialize into host- 20 specific pathogens known as formae speciales. This with the help of horizontal gene 21 transfer (HGT) between pathogenic and endophytic individuals of FOSC. From these 22 pathogenic forma specialis, F. -

Hybridization of Powdery Mildew Strains Gives Rise to Pathogens on Novel Agricultural Crop Species

LETTERS OPEN Hybridization of powdery mildew strains gives rise to pathogens on novel agricultural crop species Fabrizio Menardo1, Coraline R Praz1, Stefan Wyder1, Roi Ben-David1,4, Salim Bourras1, Hiromi Matsumae2, Kaitlin E McNally1, Francis Parlange1, Andrea Riba3, Stefan Roffler1, Luisa K Schaefer1, Kentaro K Shimizu2, Luca Valenti1, Helen Zbinden1, Thomas Wicker1,5 & Beat Keller1,5 Throughout the history of agriculture, many new crop species exclusively on tetraploid wheat as new forma specialis, B. graminis (polyploids or artificial hybrids) have been introduced to f. sp. dicocci5. diversify products or to increase yield. However, little is Overall, the genomes of the 46 isolates were very similar to each known about how these new crops influence the evolution other, allowing high-quality mapping of the 45 resequenced isolates of new pathogens and diseases. Triticale is an artificial hybrid to the 96224 reference isolate (Supplementary Note). We identified of wheat and rye, and it was resistant to the fungal pathogen between 115,543 and 332,450 polymorphic nucleotide sites per isolate powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis) until 2001 (refs. 1–3). in comparison to the B.g. tritici reference genome (Supplementary We sequenced and compared the genomes of 46 powdery Figs. 25 and 26, and Supplementary Note). Principal-component mildew isolates covering several formae speciales. We found that analysis (PCA) based on 717,701 polymorphic sites clearly distin- B. graminis f. sp. triticale, which grows on triticale and wheat, guished four groups (Fig. 1) that corresponded to the four formae is a hybrid between wheat powdery mildew (B. graminis f. sp. speciales identified in the infection tests. -

Microfungi Associated with Camellia Sinensis: a Case Study of Leaf and Shoot Necrosis on Tea in Fujian, China

Mycosphere 12(1): 430–518 (2021) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/12/1/6 Microfungi associated with Camellia sinensis: A case study of leaf and shoot necrosis on Tea in Fujian, China Manawasinghe IS1,2,4, Jayawardena RS2, Li HL3, Zhou YY1, Zhang W1, Phillips AJL5, Wanasinghe DN6, Dissanayake AJ7, Li XH1, Li YH1, Hyde KD2,4 and Yan JY1* 1Institute of Plant and Environment Protection, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, People’s Republic of China 2Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Tha iland 3 Tea Research Institute, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fu’an 355015, People’s Republic of China 4Innovative Institute for Plant Health, Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, Guangzhou 510225, People’s Republic of China 5Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Biosystems and Integrative Sciences Institute (BioISI), Campo Grande, 1749–016 Lisbon, Portugal 6 CAS, Key Laboratory for Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography of East Asia (KLPB), Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, People’s Republic of China 7School of Life Science and Technology, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, People’s Republic of China Manawasinghe IS, Jayawardena RS, Li HL, Zhou YY, Zhang W, Phillips AJL, Wanasinghe DN, Dissanayake AJ, Li XH, Li YH, Hyde KD, Yan JY 2021 – Microfungi associated with Camellia sinensis: A case study of leaf and shoot necrosis on Tea in Fujian, China. Mycosphere 12(1), 430– 518, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/12/1/6 Abstract Camellia sinensis, commonly known as tea, is one of the most economically important crops in China. -

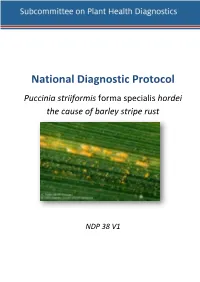

Barley Stripe Rust DP

NDP38 V1 - National Diagnostic Protocol for Puccinia striiformis f. sp. hordei National Diagnostic Protocol Puccinia striiformis forma specialis hordei the cause of barley stripe rust NDP 38 V1 NDP38 V1 - National Diagnostic Protocol for Puccinia striiformis f. sp. hordei © Commonwealth of Australia Ownership of intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence, save for content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. This publication (and any material sourced from it) should be attributed as: Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics (2016). National Diagnostic Protocol for Puccinia striiformis f. sp. hordei – NDP38 V1. (Eds. Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics) Authors Spackman, M and Wellings, C; Reviewer Cuddy, W. ISBN 978-0-9945113-4-8. CC BY 3.0. Cataloguing data Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics (date). National Diagnostic -

Taxonomy of Cronartium Quercuum and C. Fusiforme

TAXONOMY OF CRONARTIUM QUERCUUM AND C. FUSIFORME HAROLD H. BURDSALL, JR Center for Forest Mycology Research, Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Madison, Wisconsin 53705 AND GLENN A. SNOW Southern Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Gulfport, Mississippi 39501 SUMMARY Cronartium fusiforme is considered conspecific with C. quercuum based on morphological studies, but maintained as a distinct forma specialis of C. quercuum because of its restricted host range on Pinus taeda and P. elliottii. Three other special forms of C. quercuum are proposed for physiological entities that selectively attack P. banksiana, P. echinata, or P. virginiana. The importance of recognizing the con specificicity and genetic plasticity of these organisms when breeding resistant pines is emphasized. Fusiform rust, caused by Cronartium fusiforme Cumm., has long been recognized as an important disease of southern pine (Hedgcock and Siggers, 1949; Czabator, 1971). However, there is still question as to the taxonomic status of the causal organism (Hedgcock and Long, 1914; Arthur, 1915, 1934; Hedgcock and Hunt, 1918; Rhoads et al., 1918; Hedgcock and Siggers, 1949; and others). It was not until Cummins (1956, p. 603) provided a description for the perfect state that thc combination C. fusiforme was validly published. Questions are still being raised concerning the relationship between C. fusiforme and the causal organism of the eastern gall rust, C. quercuum (Berk.) Miyabe ex Shirai (Gooding and Powers, 1965; Peterson, 1967; Dwinell, 1969a : Czabator, 1971; Jewell, 1972; Kais and Snow, 1972; Powers, 1972). The relationship is accepted as being close because the two “species” have comparable life cycles, attack most of the same alternate host species.