Susan Foote Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

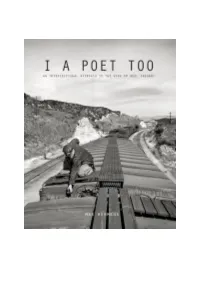

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

America Singing Loud: Shifting Representations of American National

AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English Literature By Eliza K. Waggoner Dayton, Ohio May 2012 AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Name: Waggoner, Eliza K. APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________________ Albino Carrillo, MFA Committee Chair ____________________________________________________ Tereza Szeghi, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________________________________ James Boehnlein, Ph. D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Name: Waggoner, Eliza K. University of Dayton Advisor: Mr. Albino Carrillo Much work has been done to study the writings of Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg. Existing scholarship on these two poets aligns them in various ways (radicalism, form, prophecy, etc.), but most extensively through their homosexuality. While a vast majority of the scholarship produced on these writers falls under queer theory, none acknowledges their connection through the theme of my research—American identity. Ideas of Americanism, its representation, and what it means to be an American are issues that span both Whitman and Ginsberg's work. The way these issues are addressed and reconciled by Ginsberg is vastly different from how Whitman interacts with the subject: a significant departure due to the nature of their relationship. Ginsberg has cited Whitman as an influence on his work, and other scholars have commented on the appearance of this influence. The clear evidence of connection makes their different handling of similar subject matter a doorway into deeper analysis of the interworking of these two iconic American writers. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

Of Nuclear Weapons ……………………… 323 33

Sayonara Nukes The Case for Abolishing Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapons Dennis Riches CENTER FOR GLOCAL STUDIES SEIJO UNIVERSITY in the series Seijo Glocal Studies in Society and Culture edited by Tomiyuki Uesugi, Masahito Ozawa The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the Center for Glocal Studies, the Research Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Seijo University. First published in 2018 Published by: Center for Glocal Studies, Research Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Seijo University 6-1-20, Seijo, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, 157-8511, JAPAN E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.seijo.ac.jp/research/glocal-center/ Copyright@ Center for Glocal Studies, Seijo University, Japan 2018 All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Cover design by Rokuo Design Printed and bound in Japan by Sanrei Printing Co., Ltd., Tokyo. ISBN 978-4-906845-31-6 C3036 Table of Contents Foreword Introduction ……………………………………………………………… 1 PART ONE: CINEMA, LITERATURE AND POPULAR CULTURE 1. Don Quixote and the Hyperboloid Cooling Towers ………………… 11 2. The Nuclear Age in Dylan and the Beats …………………………… 17 3. Alpha and Beta Particles Shoot Horses, Don’t They? ……………… 27 4. LOST After an Earthquake-Tsunami-Nuclear Meltdown Catastrophe ……………………………………………………………………… 33 5. Nora Ephron, Silkwood, and the Great American Romcom ………… 43 6. -

Allen Ginsberg's Many Multitudes Joseph Karwin University of Texas at Tyler

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler English Department Theses Literature and Languages Spring 5-9-2018 The heP nomenological Beat: Allen Ginsberg's Many Multitudes Joseph Karwin University of Texas at Tyler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/english_grad Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Karwin, Joseph, "The heP nomenological Beat: Allen Ginsberg's Many Multitudes" (2018). English Department Theses. Paper 17. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/1159 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Literature and Languages at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Department Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHENOMENOLOGOICAL BEAT: ALLEN GINSBERG’S MANY MULTITUDES by JOSEPH KARWIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts English Department of Literature & Languages Anett Jessop, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Graduate Studies The University of Texas at Tyler May 2018 The University of Texas at Tyler Tyler, Texas This is to certify that the Master’s Thesis of JOSEPH KARWIN has been approved for the thesis requirement on April 17, 2018 for the Master of Arts English degree © Copyright 2018 by Joseph Karwin All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................ii -

Allen Ginsberg Collected Poems, 1947-1997, 2006

Critical Survey of Poetry Ginsberg, Allen Death and Fame: Poems, 1993-1997, 1999 Allen Ginsberg Collected Poems, 1947-1997, 2006 Born: Newark, New Jersey; June 3, 1926 Other literary forms Died: New York, New York; April 5, 1997 Allen Ginsberg recognized early in his career that he would have to explain his intentions, because most Principal poetry critics and reviewers of the time did not have the inter- Howl, and Other Poems, 1956, 1996 est or experience to understand what he was trying to Empty Mirror: Early Poems, 1961 accomplish. Consequently, he published books that in- Kaddish, and Other Poems, 1958-1960, 1961 clude interviews, lectures, essays, photographs, and The Change, 1963 letters to friends as means of conveying his theories Reality Sandwiches, 1963 about composition and poetics. Kral Majales, 1965 Wichita Vortex Sutra, 1966 Achievements T.V. Baby Poems, 1967 The publication of “Howl” in 1956 drew such en- Airplane Dreams: Compositions from Journals, thusiastic comments from Allen Ginsberg’s support- 1968 ers, and such vituperative condemnation from conser- Ankor Wat, 1968 vative cultural commentators, that a rift of immense Planet News, 1961-1967, 1968 proportions developed, which has made a balanced The Moments Return, 1970 critical assessment very difficult. Nevertheless, parti- Ginsberg’s Improvised Poetics, 1971 san response has gradually given way to an acknowl- Bixby Canyon Ocean Path Word Breeze, 1972 edgment by most critics that Ginsberg’s work is signifi- The Fall of America: Poems of These States, 1965- cant, if not always entirely successful by familiar 1971, 1972 standards of literary excellence. Such recognition was The Gates of Wrath: Rhymed Poems, 1948-1952, underscored in 1974, when The Fall of America shared 1972 the National Book Award in Poetry. -

An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950S Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2012 Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessmer, Anna Lou, "Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s" (2012). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 427. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTAINING THE BEAT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PRESS COVERAGE OF THE BEAT GENERATION DURING THE 1950S A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by Anna Lou Jessmer Approved by Robert A. Rabe, Committee Chairperson Professor Janet Dooley Dr. Terry Hapney Marshall University December 2012 ii Dedication I would like to dedicate my research to my grandfather, James D. Lee. His personal experiences during the Cold War at home and abroad inspired in me a fascination of the era at an early age. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take a moment to acknowledge in writing, a few individuals without whom this paper would not be complete. I am incredibly and eternally grateful for Professor Robert A. -

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America Manuel Luis Martinez But invasion is the basis of fear: there’s no fear like invasion. -William S. Burroughs Barry Miles, biographer of both Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, gives a typical interpretation of the Beat phenomenon’s political significance: The group was more of a fraternity of spirit and at- titude than a literary movement, and their writings have little in common with each other; what they did have in common was a reaction to the ongoing car- nage of World War 11, the dropping of the A-bomb and the puritan small-mindedness that still char- acterized American life. They shared an interest in widening the area of consciousness, by whatever means available. (1992, 5) This quote is significant not only because of what Miles al- leges about the Beat writers, but also because of what he de- scribes as the Beat “reaction” to those postwar events commonly maintained as the most important. He suggests that a monolithic U.S. culture, in the throes of a puritanical con- servatism, was challenged by a group of heroic writers who countered its hypocrisy and blindness by “widening the area of consciousness.” The version of history that this view im- plies is troublesome for many reasons. First, it posits an axis Aztlan 23:l Spring 1998 33 Martinez of historical relations in which conservative arbiters of bour- geois culture are set against a subversive group that saves the decade by creating a liberating cultural movement, a move- ment that “widens”consciousness and presages the even more “liberating”countercultural movement of the 1960s. -

Wholly Communion, Literary Nationalism, and the Sorrows of the Counterculture Daniel Kane

Wholly Communion, Literary Nationalism, and the Sorrows of the Counterculture Daniel Kane all those americans here writing about america it’s time to give something back, after all our heroes were always the gangster the outlaw why surprised you act like it now, a place the simplest man was always the most complex you gave me the usual things, comics, music, royal blue drape suits & what they ever give me but unreadable books? Tom Raworth, “I Mean” These opening lines from “I Mean” by British poet Tom Raworth, published in 1967 in Raworth’s fi rst full- length collection, The Relation Ship (Goliard Press),1 stand as a kind of metaphor for a larger problem facing British avant- garde poetry in the 1960s. Put simply, “I Mean” addresses an “American” infl uence on British letters that was to weigh heavily on poets challenging the restrained formalism and hostility to the modernist project characteris- tic of the British “Movement” poets.2 How were the many Beat and Black Mountain– enamored versifi ers of Albion to be innovative on their own terms? The avant- garde, as Raworth seems to have it, is predicated on the aura of the “outlaw,” the “gangster.” Such fi gures are suggestively American, par- ticularly when read within the context of the poem’s opening lines. American signs pointing the way forward for a developing British poetics include an idealized simplicity, comics, and music.3 Raworth’s poem works in part to ask whether the English will be able to “give something back.” What would that “something” sound like? What would it look like? Would it be somehow Framework 52, No. -

From Jason Shinder (Ed.), the Poem That Changed America: 'Howl' Fifty Years Later (New York: Farrar Straus, 2006), 24-43

From Jason Shinder (ed.), The Poem that Changed America: ‘Howl’ Fifty Years Later (New York: Farrar Straus, 2006), 24-43. “A Lost Batallion of Platonic Conversationalists”: “Howl” and the Language of Modernism Marjorie Perloff In 1957, just a year after the publication of the City Lights edition of Howl, Louis Simpson wrote a poem called “To the Western World”: A siren sang, and Europe turned away From the high castle and the shepherd’s crook. Three caravels went sailing to Cathay On the strange ocean, and the captains shook Their banners out across the Mexique Bay. And in our early days we did the same, Remembering our fathers in their wreck We crossed the sea from Palos where they came And saw, enormous to the little deck, A shore in silence waiting for a name. The treasures of Cathay were never found. In this America, this wilderness Where the axe echoes with a lonely sound, The generations labour to possess And grave by grave we civilize the ground.1 Simpson had been a classmate of Ginsberg’s at Columbia University in the late forties. He was older and “wiser”—a World War II veteran who had served in the 101st Airborne Division in Europe. When the newly celebrated author of «Howl» returned to Manhattan in 1956, he sought out Simpson, who was then editing, with Donald Hall and Robert Pack, New Poets of England and America, which was to become the standard anthology used in undergraduate classrooms. Ginsberg recalls giving Simpson «this great load of manuscripts of [Robert] Duncan's, [Robert] Creeley's, [Denise] Levertov's, mine, [Philip] Lamantia's, [John] Wieners', [Gary] Snyder's, [Philip] Whalen's, [Jack] Kerouac's, even [Frank] O'Hara's —everything.