Issue 6: Conservation of Native Biodiversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quadrastichus Erythrinae Kim

Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim Unusual growths caused on leaves and young shoots of coral trees (Erythrina spp.) alerts to the presence of Erythrina gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae) a gall-forming eulophid wasp, that measures a mere 1.5mm and may be spread easily via infected leaves from infected Erythrina specimens. A newly described species Q. erythrinae is believed to be native to Africa. It is now a serious pest of Erythrina trees in the tropics Erythrina variegata, it is now reported in Miami and Hawaii, also knownand sub-tropics; from Singapore, it was firstMauritius collected and in Reunion. Florida onTaiwan, coral Hongtrees Kong, China, India, Thailand, Philippines, American Samoa, Guam and in the Amami Islands and Okinawa in Japan Erythrina spp. have a variety of functions in different locations. activities. As indicated by its Latin name “erythros” meaning red, In Taiwan they are highly associated with farming and fishing its obvious red flowers have been used as a sign of the arrival of spring and as a working calendar by tribal peoples. Specifically, peoplethe blooming (the Puyama of its showy people) red to flowers plant sweetsignal potatoesto the coastal (Yang people et al. 2004).to begin their ceremonies for catching flying fish, and for another Photo credit: Kim & Forest Starr The Erythrina gall wasp infests E. variegata, E. crista-galli and the Short-term control options are limited. The application of a systemic native E. sandwicensis in Hawaii (Heu et al. 2006). E. sandwicensi, insecticide appears to have been partly effective in protecting known as the wiliwili tree, is endemic to Hawaii and a keystone highly valued individual trees in Hawaii. -

Migratory Shorebirds Management Plan

Report GLNG Curtis Island Marine Facilities Migratory Shorebirds Environmental Management Plan 17 MARCH 2011 Prepared for GLNG Operations Pty Ltd Level 22 Santos Place 32 Turbot Street Brisbane Qld 4000 42626727 Project Manager: URS Australia Pty Ltd Level 16, 240 Queen Street Angus McLeod Brisbane, QLD 4000 Senior Ecologist GPO Box 302, QLD 4001 Australia T: 61 7 3243 2111 Principal-In-Charge: F: 61 7 3243 2199 Chris Pigott Senior Principal Author: Angus McLeod Senior Ecologist Reviewer: Date: 17 March 2011 Reference: 42626727/01/03 Status: Final Chris Pratt Principal Environmental Scientist j:\jobs\42626727\5 works\draft emp\for tina 17.3.11\3310-glng-3-3 3-0065_shorebirds_final_17 03 2011.doc Table of Contents Abbreviations............................................................................................................iii Executive Summary..................................................................................................iv 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background .........................................................................................1 1.2 Purpose of the Migratory Shorebirds Environment Management Plan ...................................................................................................................1 1.3 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................3 1.4 Study Area ........................................................................................................3 -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Erythrina Gall Wasp, Quadrastichus Erythrinae Kim, in Florida

FDACS-P-01700 Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Charles H. Bronson, Commissioner of Agriculture Erythrina Gall Wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim, in Florida James Wiley, [email protected], Taxonomic Entomologist, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Divsion of Plant Industry Paul Skelley, [email protected], Taxonomic Entomologist, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry INTRODUCTION: Galls of the eulophid erythrina gall wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim 2004, were first collected in Florida by Edward Putland and Olga Garcia (Florida Department of Agriculture, Division of Plant Industry) on Erythrina variegata L. in Miami-Dade County at the Miami Metro Zoo on October 15, 2006. Erythrina variegata, also known as coral tree, tiger’s claw, Japanese coral tree, Indian coral tree, and wiliwili-haole, is noted for its seasonal showy red flowers and variegated leaves. It is an ornamental landscape tree widely planted in the southern part of the state. Erythrina is a large genus with approximately 110 different species worldwide. In addition to Erythrina variegata, the erythrina gall wasp has been collected on E. crista-galli L., E. sandwicensis Deg., and E. stricta Roxb. It is uncertain at this time how many species of Erythrina the erythrina gall wasp may attack in Florida. DISTRIBUTION: The erythrina gall wasp is believed to have originated in Africa, but this remains uncertain. It was described (Kim et al 2004) from specimens from Singapore, Mauritius, and Reunion. In the past two years, it has spread to China, India, Taiwan, Philippines, and Hawaii (Heu et al 2006; Schmaedick et al 2006; ISSG 2006). -

Effect of Temperature on Life History of Quadrastichus Haitiensis

Biological Control 36 (2006) 189–196 www.elsevier.com/locate/ybcon Effect of temperature on life history of Quadrastichus haitiensis (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), an endoparasitoid of Diaprepes abbreviatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) J. Castillo a, J.A. Jacas b,*, J.E. Pen˜a a, B.J. Ulmer a, D.G. Hall c a University of Florida/IFAS, Tropical Research and Education Center, 18905 SW 280th Street, Homestead, FL 33031, USA b Departament de Cie`ncies Experimentals, Universitat Jaume I, Campus del Riu Sec, E-12071-Castello´ de la Plana, Spain c USDA, USRHL, Fort Pierce, FL 34945, USA Received 9 May 2005; accepted 26 September 2005 Available online 13 December 2005 Abstract The influence of temperature on life history traits of the egg parasitoid Quadrastichus haitiensis (Gahan) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) was investigated in the laboratory on eggs of the root weevil Diaprepes abbreviatus (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Duration of devel- opment from egg to adult decreased from 39.99 ± 0.27 days to 13.57 ± 0.07 days (mean ± SE) as temperature increased from 20 to 33 °C, respectively. No development was observed at 5–15 °C. Fecundity was highest at 25 and 30 °C (70–73 eggs per female) but was reduced at 33 °C (21.5 eggs per female). Oviposition rate was also reduced at 33 °C. Q. haitiensis accepted host eggs from 0 to 7 days old for oviposition but was most prolific when parasitizing 1- to 4-day-old eggs. Very few adult Q. haitiensis emerged from host eggs that were 5–7 days old, however, D. abbreviatus egg mortality was similar for eggs 0–7 days old. -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Rangi Above/Papa Below, Tangaroa Ascendant, Water All Around Us: Austronesian Creation Myths

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths Amy M Green University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Green, Amy M, "Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1938. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/b2px-g53a This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RANGI ABOVE/ PAPA BELOW, TANGAROA ASCENDANT, WATER ALL AROUND US: AUSTRONESIAN CREATION MYTHS By Amy M. Green Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1436751 Copyright 2006 by Green, Amy M. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Tringarefs V1.3.Pdf

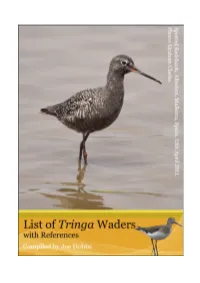

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2016 & 2017 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and best employed in conjunction with other reference sources. Grateful thanks to Graham Clarke (http://grahamsphoto.blogspot.com/) and Tom Shevlin (www.wildlifesnaps.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds). 2016. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 6.1 accessed February 2016]). Version Version 1.3 (March 2016). Cover Main image: Spotted Redshank. Albufera, Mallorca. 13th April 2011. Picture by Graham Clarke. Vignette: Solitary Sandpiper. Central Bog, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 29th August 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Greater Yellowlegs [Tringa melanoleuca] 14 Green Sandpiper [Tringa ochropus] 16 Greenshank [Tringa nebularia] 11 Grey-tailed Tattler [Tringa brevipes] 20 Lesser Yellowlegs [Tringa flavipes] 15 Marsh Sandpiper [Tringa stagnatilis] 10 Nordmann's Greenshank [Tringa guttifer] 13 Redshank [Tringa totanus] 7 Solitary Sandpiper [Tringa solitaria] 17 Spotted Redshank [Tringa erythropus] 5 Wandering Tattler [Tringa incana] 21 Willet [Tringa semipalmata] 22 Wood Sandpiper [Tringa glareola] 18 1 Relevant Publications Bahr, N. 2011. The Bird Species / Die Vogelarten: systematics of the bird species and subspecies of the world. Volume 1: Charadriiformes. Media Nutur, Minden. Balmer, D. et al 2013. Bird Atlas 2001-11: The breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. -

Nov. 24Th – 7:00 Pm by Zoom Doors Will Open at 6:30

Wandering November 2020 Volume 70, Number 3 Tattler The Voice of SEA AND SAGE AUDUBON, an Orange County Chapter of the National Audubon Society Why Do Birders Count Birds? General Meeting - Online Presentation th Gail Richards, President Friday, November 20 – 7:00 PM Via Zoom Populations of birds are changing, both in the survival of each species and the numbers of birds within each “Motus – an exciting new method to track species. In California, there are 146 bird species that are vulnerable to extinction from climate change. These the movements of birds, bats, & insects” fluctuations may indicate shifts in climate, pollution levels, presented by Kristie Stein, MS habitat loss, scarcity of food, timing of migration or survival of offspring. Monitoring birds is an essential part of protecting them. But tracking the health of the world’s 10,000 bird species is an immense challenge. Scientists need thousands of people reporting what they are seeing in their back yards, neighborhoods, parks, nature preserves and in all accessible wild areas. Even though there are a number of things we are unable to do during this pandemic, Sea and Sage volunteers are committed to continuing bird surveys (when permitted, observing Covid-19 protocols). MONTHLY SURVEYS: Volunteers survey what is out there, tracking the number of species and their abundance. San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary UCI Marsh Kristie Stein is a Wildlife Biologist with the Southern University Hills Eco Reserve Sierra Research Station (SSRS) in Weldon, California. Upper Newport Bay by pontoon boat Her research interests include post-fledging ecology, seasonal interactions and carry-over effects, and SEASONAL SURVEYS AND/OR MONITORING: movement ecology. -

A New Species of Quadrastichus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae): a Gall-Inducing Pest on Erythrina (Fabaceae)

J. HYM. RES. Vol. 13(2), 2004, pp. 243–249 A New Species of Quadrastichus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae): A Gall-inducing Pest on Erythrina (Fabaceae) IL-KWON KIM, GERARD DELVARE, AND JOHN LA SALLE (IKK, JLS) CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; email: [email protected] (GD) CIRAD TA 40L, Campus International de Baillarguet-Csiro, 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5, France; email: [email protected] Abstract.—Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim sp.n. is described from Singapore, Mauritius and Re´- union. This species forms galls on the leaves, stems, petioles and young shoots of Erythrina var- iegata and E. fusca in Singapore, on the leaves of E. indica in Mauritius, and on Erythrina sp. in Re´union. It can cause extensive damage to the trees. Key words.—Hymenoptera, Eulophidae, Quadrastichus, phytophagous, gall inducer, Singapore, Mauritius, Erythrina, Fabaceae Species of Eulophidae are mainly para- 1988; Redak and Bethke 1995; Headrick et sitoids, but secondary phytophagy in the al. 1995); Epichrysocharis burwelli Schauff form of gall induction has arisen on many (Schauff and Garrison 2000); and Leptocybe occasions (Boucˇek 1988; La Salle 1994; invasa Fisher & La Salle (Mendel et al. Headrick et al. 1995; Mendel et al. 2004; 2004). Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim sp.n. La Salle 2004). Gall-inducing Eulophidae has recently achieved pest status in Sin- generally belong to two groups: Opheli- gapore, Mauritius and Re´union. Erythrina mini is an Australian lineage which con- trees have been grown in these areas for sists mainly of gall inducers on eucalypts, decades, and this species has never been but perhaps also on some other myrta- recorded from them.