View Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Dedicated to Serving the Needs of the Music & Record Worldindustry

record Dedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record worldIndustry May 11, 1969 60c In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO IN SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK THE WORLD -.A.11111111." LOVE MI TONIGHT TON TOWS Tom Jones, clicking on Young -HoltUnlimited have JerryButlerhas a spicy Bob Dylan sings his pretty stateside TV these days, a new and funky ditty and moodyfollow-up in "I Threw ftAll Away" (Big shouldscoreveryheavily called "Young and Holtful" "Moody Woman" (Gold Sky, ASCAP), which has with"Love Me Tonight" (Dakar - BRC, BMI), which Forever-Parabut, BMI(,pro- caused muchtalkinthe (Duchess, BMI)(Parrot hassomejazzandLatin duced by Gamble -Huff (Mer- "NashvilleSkyline"elpee 40038(. init (Brunswick 755410). cury 72929). (Columbia 4-448261. SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK TELLING ALRIGHT AM JOE COCKER COLOR HIM FATHER THE WINSTONS Joe Cocker sings the nifty The Winstons are new and Roy Clark recalls his youth TheFive Americans geta Traffic ditty that Dave will make quite a name for on the wistful Charles Az- lot funkier and funnier with Mason wrote, "FeelingAl- themselveswith"Color navour - Herbert Kretzmer, "IgnertWoman" (Jetstar, right" (Almo, ASCAP). Denny Him Father"(Holly Bee, "Yesterday,When I Was BMI(, which the five guys Cordell produced (A&M BMI), A DonCarrollPra- Young"(TRO - Dartmouth, wrote (Abnak 137(. 1063). duction (Metromedia117). ASCAP) (Dot 17246). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK ONUTISNINF lUICICCIENS GOLD "Don Kirshner Cuts 'Hair' " RogerWilliams plays "MacKenna's Gold," one of Larry Santos is a newcomer is just what the title says "HappyHeart" andalso the big summer movies, has with a big,huskyvoice I hree Records from 'Hair' withHerbBernsteinsup- getsmuchivorymileage a scorebyQuincy Jones and a good way with tune- plying arrangements and from "Those Were the and singing byJoseFeli- smithing. -

Clangxboomxstea ... Vxtomxwaitsxxlxterxduo.Pdf

II © Karl-Kristian Waaktaar-Kahrs 2012 Clang Boom Steam – en musikalsk lesning av Tom Waits’ låter Forsidebilde: © Massimiliano Orpelli (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Konsertbilde side 96: © Donna Meier (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III IV Forord Denne oppgaven hadde ikke vært mulig uten støtten fra noen flotte mennesker. Først av alt vil jeg takke min veileder, Stan Hawkins, for gode innspill og råd. Jeg vil også takke ham for å svare på alle mine dumme (og mindre dumme) spørsmål til alle døgnets tider. Spesielt i den siste hektiske perioden har han vist stor overbærenhet med meg, og jeg har mottatt hurtige svar selv sene fredagskvelder! Jeg skulle selvfølgelig ha takket Tom Waits personlig, men jeg satser på at han leser dette på sin ranch i «Nowhere, California». Han har levert et materiale som det har vært utrolig morsomt og givende å arbeide med. Videre vil jeg takke samboeren min og mine to stadig større barn. De har latt meg sitte nede i kjellerkontoret mitt helg etter helg, og all arbeidsroen jeg har hatt kan jeg takke dem for. Jeg lover dyrt og hellig å gjengjelde tjenesten. Min mor viste meg for noen år siden at det faktisk var mulig å fullføre en masteroppgave, selv ved siden av en krevende fulltidsjobb og et hektisk familieliv. Det har gitt meg troen på prosjektet, selv om det til tider var slitsomt. Til sist vil jeg takke min far, som gikk bort knappe fire måneder før denne oppgaven ble levert. Han var alltid opptatt av at mine brødre og jeg skulle ha stor frihet til å forfølge våre interesser, og han skal ha mye av æren for at han til slutt endte opp med tre sønner som alle valgte musikk som sin studieretning. -

Name Year Date Place Year Date Place Adolphe Sax 1814 11.06

Name Birthday Deathday Year Date Place Year Date Place Adolphe Sax 1814 11.06 Dinant, Belgium 1894 2.07 Paris, France Victor Herbert 1859 2.01 Dublin, Ireland 1924 5.26 New York, NY Scott Joplin 1868 11.24 Bowie City, TX 1917 4.01 New York, NY Otto Harbach 1873 8.18 Salt LakeCity, UT 1963 1.24 New York, NY William C. Handy 1873 11.16 Muscle Shoals, AL 1958 3.28 New York, NY Fred Fisher 1875 9.3 Cologne, Germany 1942 1.14 New York, NY Buddy Bolden 1877 9.06 New Orleans, LA 1931 11.04 Jackson, LA Mamie Smith 1883 5.26 Cincinnati, OH 1946 8.16 New York, NY Isham Jones 1884 1.31 Coalton, OH 1956 10.19 Hollywood, FL Jerome Kern 1885 1.27 New York, NY 1945 11.11 New York, NY King Oliver 1885 5.11 New Orleans, LA 1938 4.08 Savannah, GA Art Hickman 1886 6.13 Oakland, CA 1930 1.16 San Francisco, CA Gus Kahn 1886 11.06 Coblentz, Germany 1941 10.08 Beverly Hills, CA Kid Ory 1886 12.25 La Place, LA 1973 1.23 Honolulu, HI Ma Rainey 1886 4.26 Columbus, GA 1939 12.22 Columbus, GA Luckey Roberts 1887 8.07 Philadelphia, PA 1968 2.05 New York, NY Irving Berlin 1888 5.11 Tumen, Russia 1989 9.22 New York, NY Tom "Red" Brown 1888 6.03 New Orleans, LA 1958 3.25 New Orleans, LA Freddie Keppard 1889 2.27 New Orleans, LA 1933 12.21 Chicago, IL Nick LaRocca 1889 4.11 New Orleans, LA 1961 2.22 New Orleans, LA Jelly Roll Morton 1890 10.2 New Orleans, LA 1941 7.1 Los Angeles, CA Paul Whiteman 1890 4.28 Denver, CO 1967 12.29 New Hope, PA Cole Porter 1891 6.09 Peru, IN 1964 10.15 Santa Monica, CA Fred E. -

Vocal Ecosystems Beyond Pedagogy: Working with Challenges

Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal (LICEJ), Special Issue, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2015 Vocal Ecosystems Beyond Pedagogy: Working With Challenges Jeri Brown Concordia University Canada Abstract Knowledge of vocal improvised music, whether demonstrated in the communication of the two demonstrated by high or low obscure pitch sounds, principal artists. The use of tone matching also the beating of the chest while making music sounds, stimulates the harmonic musical language and mood vocal pitch matching or vocal animation with or in this piece. In both pieces, composer, trumpet and without the use of technology, has paved the way for flugelhorn player Kenny Wheeler creates poetic a steady stream of vocal artists through the years, artistry with voice, tenor and arranged orchestra. each dedicated to vocal exploration. While jazz vocal Horn and voice are well suited to the complex improvisation appears on the surface to involve few material fusing personas in the signature over or no rules, it is a form of communication between layering of cadenzas that reoccur in his works with a artist and listener, where the artist adheres to a set focus on emotion and sentiment [4]. of rules or principles. Here the jazz improviser is The use of vocal language and musical treated as part of an ecosystem, a concept in the intelligence in improvisation creates added biological sciences that comprises a set of stimulation in the improvised vocal delivery. interacting organisms and environments in a particular place. Within the jazz vocal 2. Characteristics of jazz vocal improvisational ecosystem there are various roles, improvisation approaches and activities. -

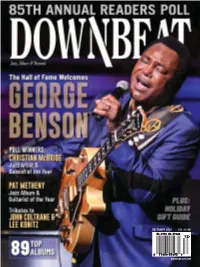

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

2018 Program Book 2007 Conference Program.Qxd

Alabama A&M University Choir The Alabama A&M University Choir, directed by Dr. Horace Carney, provides students with the opportunity to experience participation in a cooperative activity. Emphasis is placed on fundamental vocal training, posture, breathing, sight-reading, expressive interpretation and tone development. The choir performs for campus convocations, off-campus concerts, religious services, radio and television appearances as well as a Christmas Musicale and spring concert. There is a prerequisite for participation: students must have had some experience in a high school choir or ensemble. Dr. Horace R. Carney, Jr. was born in Nashville, Tennessee but grew up in Tuskegee, Alabama. He graduated with honors from Tuskegee Institute High School fourth in his class. His post-secondary education includes a Bachelor of Arts in Music at Fisk University (magna cum laude), Master of Arts in Music Theory at the Eastman School of Music as a Woodrow Wilson Fellow, and the Doctor of Philosophy in Music Theory from the University of Iowa. He has attended choral workshops at Potsdam Choral Institute, Sarasota, New York, University of South Florida, and Georgia State University. Dr. Carney’s career in music began in elementary school and continued through high school as a member of the choir, pianist, and leader of a dance band. While in high school, he studied at Tuskegee Institute with Lexine Weeks, Charlotte Giles, and Hildred Roach. His studies continued at Fisk University as a music major, a member of the university choir and the renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers for four years. His professional career includes Talladega College where he served for fourteen years as Choral Director and Acting Chairman of the Music Department, Lincoln University, Lincoln, PA; Coordinator of Choral Activities and Chairman of the Humanities Division for three years; and Sixth Avenue Baptist Church, where he served as Minister of Music and Coordinator of Cultural Affairs. -

How Mimi Perrin Translated Jazz Instrumentals Into French Song

BENJAMIN GIVAN How Mimi Perrin Translated Jazz Instrumentals into French Song “Just like the th at the beginning of they and at the beginning of theater.” “What’s different about the sound of theater and they?” “Say them again and listen. One’s voiced and the other’s unvoiced, they’re as distinct as V and F; only they’re allophones—at least in British English; so British- ers are used to hearing them as though they were the same phoneme.” —Samuel R. Delany, Babel- 171 —Prenez par exemple, en français, le C de cure et de constitution. —Quelle est la différence? —Répétez chaque mot en vous écoutant bien. Le premier est palatal, articulé sur le sommet du palais, et le second vélaire, sur le voile du palais. Il s’agit simplement de variantes combinatoires dues à l’environnement. —Samuel R. Delany, Babel- 17, translated by Mimi Perrin2 Translating prose from one language to another can often be a thorny task, especially with a text, such as the above extract from Samuel R. Delany’s Babel- 17, whose meaning or literary effect is inseparable from its voiced sound. For the French edition of this 1966 science fiction novel, its translator, Mimi Perrin (1926–2010), had little choice but to completely recompose Delany’s paragraph. Where the English original contrasts “they” with “theater” to illustrate voiced and unvoiced phonemes, she instead cites the French words cure and constitution to demonstrate palatal and velar pronunciations of the consonant c, meanwhile omitting Dela- ny’s comparison of American and British English. To convey the author’s argument about interlingual phonetic perception, she had to forgo his text’s literal word- for- word meaning and transpose its fictional setting Benjamin Givan is associate professor of music at Skidmore College. -

U P S Frrai L

* * * * * * * * UPS-PL U Review and Football Game Pictures of Tomorrow at U P S RRAIF L Judy Collins 1:30—Page 6 Concert - Page 4 NOVEMBER * * * * 1965-1966—NO. 7 5, 1965 * * * * Giovanni Costigaii A&L Schedules To Speak at UPS Dr. Giovanni Costigan, profes- sor of history at the University of Swingle Singers Washington, will speak at UPS Tuesday evening, November 17, The Swingle Singers, jazz volalists, appear at the UPS at 8 p.m. Fieldhouse as part of the college's Artist and Lecture Pro- Sponsored by the Academic Lecture Series of the Artist and gram. They perform at 8:15 j.m., Saturday, Nov. 13. Lecture program, Costigan's sub- The Swingle Singers, a group shown later this year. The singers ject will be "The Importance of of seven French singers, are led have also performed at the White Freud for the Modern World." by Ward Swingle. Their music is House for a dinner given by Pres- Macmillan Co. recently pub- Classical with a swing, adding a ident and Mrs. Johnson for Is- lished Dr. Costigan's book, Life jazz beat of bass and drums to rael's Prime Minister, Levi Esh- of Freud, and his lecture should such artists as Bach, Handel and kol. prove interesting to all students, Mozart. "The main ingredients of Ward Swingle, the Alabama- since the interpretation of Freud the Swingle formula," appraises born director of the Swingle Sing- carries meaning in history, litera- Dom Cerulli, "are respect for the ers, organized the group and has ture, education, social work and original writing and for the com- adapted and arranged all of their other fields beside psychology and posers' intentions. -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian. -

Tom Waits Foreign Affairs Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tom Waits Foreign Affairs mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Foreign Affairs Country: US Style: Blues Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1143 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1140 mb WMA version RAR size: 1896 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 347 Other Formats: MPC XM WMA APE MMF VOC DMF Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Cinny's Waltz 2:16 A2 Muriel 3:33 I Never Talk To Strangers A3 3:37 Featuring [Co-starring] – Bette Midler Medley (5:00) A4a Jack & Neal California Here I Come A4b Written-By – Al Jolson, Buddy G. De Sylva, Joseph Meyer A6 A Sight For Sore Eyes 4:39 Potter's Field B1 8:38 Clarinet, Soloist – Gene CiprianoMusic By – Bob AlcivarWords By – Tom Waits B2 Burma Shave 6:32 B3 Barber Shop 3:52 B4 Foreign Affair 3:46 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Filmways/Heider Recording Mastered At – Elektra Sound Recorders Published By – Warner Bros. Music Ltd. Published By – B. Feldman & Co. Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Elektra/Asylum Records Copyright (c) – Elektra/Asylum Records Made By – WEA Musik GmbH Pressed By – Record Service GmbH Lacquer Cut At – Strawberry Mastering Credits Arranged By [Orchestra], Conductor – Bob Alcivar Art Direction, Design – Glen Christensen Bass – Jim Hughart Drums – Shelly Manne Engineer [2nd] – Geoff Howe Management [Orchestra Managers] – Edgar Lustgarten , Jim Robak Mastered By [Disc Mastering] – Terry Dunavan Photography By – George Hurrell Piano, Vocals – Tom Waits Producer, Other [Sound By], Engineer – Bones Howe Tenor Saxophone, Soloist – Frank Vicari Trumpet, Soloist – Jack Sheldon Written-By – Tom Waits (tracks: A1 to A4a, A6, B2 to B4) Notes Sleeve: ℗&© 1977 Elektra/Asylum Records Made in Germany by WEA Musik GmbH A Warner Communications Company Inner Sleeve: A Mr. -

Download Booklet

1 A Fifth of Beethoven (feat. Shlomo) 3.09 7 Cielito Lindo (Mexican Traditional) 4.49 the swingle singers Ludwig van Beethoven / Walter Murphy, Quirino Mendoza y Cortes, arr. Tobias Hug arr. Itay Avramovitz human beatbox: Shlomo leads: Kineret, Tom vocal percussion: everyone! 2 Spain (I Can Recall) 6.24 Joaquin Rodrigo / Chick Corea / Al Jarreau / 8 Straighten Up and Fly Right 5.02 Artie Maren, arr. Scott Stroman Nat King Cole / Irving Mills, solos: Tom, Kineret arr. Bertrand Groeger vocal percussion: Jeremy lead: Tobias vocal percussion: Tom 3 Dido’s Lament 4.20 and the Henry Purcell, arr. Tom Bullard 9 Piano Concerto No.21, 2nd mvt 3.38 lead: Johanna Beauty Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, human beatbox: Tobias arr. Jonathan Rathbone leads: Johanna, Julie 4 It’s Sand, Man! 2.32 vocal percussion: Jeremy Ed Lewis / Jon Hendricks / Dave Lambert, arr. Ward Swingle bl Gotcha (Theme from “Starsky & Hutch”) 4.01 lead: Kineret Tom Scott, arr. Adam Riley vocal percussion: Jeremy solos: Kineret, Johanna vocal percussion: Jeremy 5 Adagio in G Minor 5.48 Tomaso Albinoni / Remo Giazotto, bm Bachbeat 2.36 arr. Tom Bullard ( feat. Shlomo, MC Zani, Bellatrix, BEATBOX leads: Julie, Kineret, Johanna Spitf’ya and jestar*) human beatbox: Jeremy Written by Shlomo and the Vocal Orchestra with the Swingle Singers featuring 6 Bolero 8.28 (based on Badinerie by J.. S. Bach, Maurice Ravel, arr. Tom Bullard arr. Ward Swingle) solos: Julie, Joanna, Richard, Tobias lead vocals: Joanna Shlomo vocal percussion: Jeremy … make it funky now Visit www.swinglesingers.com and the -

1970-05-23 Milwaukee Radio and Music Scene Page 30

°c Z MAY 23, 1970 $1.00 aQ v N SEVENTY -SIXTH YEAR 3 76 D Z flirt s, The International Music-Record-Tape Newsweekly COIN MACHINE O r PAGES 43 TO 46 Youth Unrest Cuts SPOTLIGHT ON MCA -Decca in Disk Sales, Dates 2 -Coast Thrust By BOB GLASSENBERG NEW YORK - The MCA - Decca was already well- estab- NEW YORK -Many campus at Pop -I's Record Room. "The Decca Records complex will be lished in Nashville. record stores and campus pro- strike has definitely affected our established as a two -Coast corn- In line with this theory, Kapp moters Records is being moved to the across the country are sales. Most of the students have pany, Mike Maitland, MCA Rec- losing sales and revenue because gone to the demonstrations in West Coast as of May 15. Sev- of student political activity. "The the city and don't have new ords president, said last week. eral employees have been students are concerned with records on their minds at the "There are no home bases any- shifted from Kapp's New York other things at the moment," moment. They are deeply moved more for the progressive record operation into the Decca fold according to the manager of the (Continued on page 40) company." He pointed out that and Decca will continue to be a Harvard Co -op record depart- New York -focused firm. The ment in Cambridge, Mass. The shift of Kapp to Los Angeles is record department does much a "rather modest change," business with students in the FCC Probing New Payola Issues Maitland said, as part of the Boston area.