Kashmir Flycatcher Pale Rock Sparrow Ernst Schäfer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species List

Dec. 11, 2013 – Jan. 01, 2014 Thailand (Central and Northern) Species Trip List Compiled by Carlos Sanchez (HO)= Distinctive enough to be counted as heard only Summary: After having traveled through much of the tropical Americas, I really wanted to begin exploring a new region of the world. Thailand instantly came to mind as a great entry point into the vast and diverse continent of Asia, home to some of the world’s most spectacular birds from giant hornbills to ornate pheasants to garrulous laughingthrushes and dazzling pittas. I took a little over three weeks to explore the central and northern parts of this spectacular country: the tropical rainforests of Kaeng Krachen, the saltpans of Pak Thale and the montane Himalayan foothill forests near Chiang Mai. I left absolutely dazzled by what I saw. Few words can describe the joy of having your first Great Hornbill, the size of a swan, plane overhead; the thousands of shorebirds in the saltpans of Pak Thale, where I saw critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper; the tear-jerking surprise of having an Eared Pitta come to bathe at a forest pool in the late afternoon, surrounded by tail- quivering Siberian Blue Robins; or the fun of spending my birthday at Doi Lang, seeing Ultramarine Flycatcher, Spot-breasted Parrotbill, Fire-tailed Sunbird and more among a 100 or so species. Overall, I recorded over 430 species over the course of three weeks which is conservative relative to what is possible. Thailand was more than a birding experience for me. It was the Buddhist gong that would resonate through the villages in the early morning, the fresh and delightful cuisine produced out of a simple wok, the farmers faithfully tending to their rice paddies and the amusing frost chasers at the top of Doi Inthanon at dawn. -

Download Download

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp, Hem Sagar Baral, Tfm Inskfpp, Ambfka Prasad Khafwada, Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada, Laxman Prasad Poudyal & Rajan Amfn 26 January 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 1 | Pp. 9700–9722 10.11609/jot. 2855 .9.1. 9700-9722 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT.asp For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes.asp For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct.asp For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 January 2017 | 9(1): 9700–9722 Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp 1 , Hem Sagar Baral 2 , Tfm Inskfpp 3 , Ambfka Prasad Khafwada 4 , 5 6 7 ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada , Laxman Prasad -

Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula Albicilla in Gujarat: Status and Distribution, with Notes on Its Identification Prasad Ganpule

152 Indian BirDS Vol. 9 Nos. 5&6 (Publ. 2 December 2014) Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicilla in Gujarat: Status and distribution, with notes on its identification Prasad Ganpule Ganpule, P., 2014. Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicilla in Gujarat: Status and distribution, with notes on its identification. Indian BIRDS 9 (5&6): 152–154. Prasad Ganpule, C/o Parshuram Pottery Works, Opp.Nazarbaug Station, Morbi 363642, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received on 11 May 2014. Introduction The record from Thol, near Ahmedabad (Maheria 2014), The Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicilla is a winter migrant to identified as an Asian Brown FlycatcherM. dauurica is actually India. Its winter distribution is mainly to north-eastern, eastern, a F. albicilla. and central India, and the Eastern Ghats, reaching up to western Maharashtra, and Goa (Rasmussen & Anderton 2005; Grimmett Identification et al. 2011). No sightings from Gujarat are given in these texts, Since it is now established that F. parva, F. albicilla, and the but it has been reported from Morbi, Gujarat (Ganpule 2013), Kashmir Flycatcher F. subrubra occur in Gujarat (Grimmett et with the sighting of an adult male in April 2011. al. 2011; Ganpule 2012), identification and separation of the three in first winter plumage is quite challenging. Cederroth et Observations al. (1999) deal with the identification ofparva and albicilla. For I always suspected that the Taiga Flycatcher was more common the identification of first winterF. subrubra, see Ganpule (2012). in Gujarat than previously expected, and it could have been Some additional notes on identification of first-winterF. albicilla overlooked since it was considered a subspecies of the Red- are presented below: breasted Flycatcher F. -

The Female/First Winter Kashmir Flycatcher Ficedula Subrubra: an Identification Conundrum Prasad Ganpule

GANPULE: Kashmir Flycatcher 153 The female/first winter Kashmir Flycatcher Ficedula subrubra: an identification conundrum Prasad Ganpule Ganpule, P., 2012. The female/first winter Kashmir Flycatcher Ficedula subrubra: an identification conundrum. Indian BIRDS 7 (6): 153–158. Prasad Ganpule, C/o Parshuram Pottery Works, Opp. Nazarbaug Station, Morbi 363642, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] Manuscript first received on 24 May 2011. Introduction Observations The Kashmir Flycatcher Ficedula subrubra is endemic to the The bird in question had orange spotting/mottling on the breast, Indian Subcontinent. It is a Red Data species categorised as which was almost absent on its white throat, extending up to Vulnerable (BirdLife International 2011). It breeds in the Kashmir the flanks. It had a white belly. It had darker/blackish wings, area and Pir Panjal Range (Bates & Lowther 1952; Henry 1955; grey on the sides of the neck, and dark brownish upperparts. Roberts 1992), and is known to winter in the Western Ghats and The tail and rump were completely black. It had a greyish-black Sri Lanka (Zarri & Rahmani 2004b). bill with a pale base to the lower mandible. The bill looked At c. 0900 hrs on 2 January 2009, in a patchwork habitat slightly longer and stronger than the bill of a typical parva. I comprising cultivation, scattered trees, and scrub near Morbi, took numerous photographs, referred books, and prima facie Rajkot district, Gujarat (22º49’N, 70º50’E) I heard a loud and identified the bird as a female Kashmir Flycatcher based on clear bird call: “sweet-sweet,” similar to the call of an Indian Robin the call and other identification features. -

Žƶƌŷăů ŽĨ Dśƌğăƚğŷğě Dădžă

KWE^^ ůůĂƌƟĐůĞƐƉƵďůŝƐŚĞĚŝŶƚŚĞ:ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨdŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚdĂdžĂĂƌĞƌĞŐŝƐƚĞƌĞĚƵŶĚĞƌƌĞĂƟǀĞŽŵŵŽŶƐƩƌŝďƵƟŽŶϰ͘Ϭ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂͲ ƟŽŶĂů>ŝĐĞŶƐĞƵŶůĞƐƐŽƚŚĞƌǁŝƐĞŵĞŶƟŽŶĞĚ͘:ŽddĂůůŽǁƐƵŶƌĞƐƚƌŝĐƚĞĚƵƐĞŽĨĂƌƟĐůĞƐŝŶĂŶLJŵĞĚŝƵŵ͕ƌĞƉƌŽĚƵĐƟŽŶĂŶĚ ĚŝƐƚƌŝďƵƟŽŶďLJƉƌŽǀŝĚŝŶŐĂĚĞƋƵĂƚĞĐƌĞĚŝƚƚŽƚŚĞĂƵƚŚŽƌƐĂŶĚƚŚĞƐŽƵƌĐĞŽĨƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶ͘ :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨdŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚdĂdžĂ dŚĞŝŶƚĞƌŶĂƟŽŶĂůũŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĂŶĚƚĂdžŽŶŽŵLJ ǁǁǁ͘ƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐ /^^EϬϵϳϰͲϳϵϬϳ;KŶůŝŶĞͿͮ/^^EϬϵϳϰͲϳϴϵϯ;WƌŝŶƚͿ ÊÃÃçÄ®ã®ÊÄ ò®¥çÄÊ¥«Ã®ÝãÙ®ã͕,®Ã«½WÙÝ«͕/Ä®ó®ã« ÃÖ«Ý®ÝÊÄ<½ãÊÖͲ<«¹¹®Ùt®½½®¥^ÄãçÙùÄ®ãÝ ÝçÙÙÊçÄ®Ä¦Ý dĂƌŝƋŚŵĞĚ^ŚĂŚ͕sŝƐŚĂůŚƵũĂ͕DĂƌƟŶĂŶĂŶĚĂŵΘŚĞůŵĂůĂ ^ƌŝŶŝǀĂƐƵůƵ Ϯϲ:ĂŶƵĂƌLJϮϬϭϲͮsŽů͘ϴͮEŽ͘ϭͮWƉ͘ϴϯϯϯʹϴϯϱϳ ϭϬ͘ϭϭϲϬϵͬũŽƩ͘ϭϳϳϰ͘ϴ͘ϭ͘ϴϯϯϯͲϴϯϱϳ &Žƌ&ŽĐƵƐ͕^ĐŽƉĞ͕ŝŵƐ͕WŽůŝĐŝĞƐĂŶĚ'ƵŝĚĞůŝŶĞƐǀŝƐŝƚŚƩƉ͗ͬͬƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐͬďŽƵƚͺ:Ždd͘ĂƐƉ &ŽƌƌƟĐůĞ^ƵďŵŝƐƐŝŽŶ'ƵŝĚĞůŝŶĞƐǀŝƐŝƚŚƩƉ͗ͬͬƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐͬ^ƵďŵŝƐƐŝŽŶͺ'ƵŝĚĞůŝŶĞƐ͘ĂƐƉ &ŽƌWŽůŝĐŝĞƐĂŐĂŝŶƐƚ^ĐŝĞŶƟĮĐDŝƐĐŽŶĚƵĐƚǀŝƐŝƚ ŚƩƉ͗ͬͬƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐͬ:ŽddͺWŽůŝĐLJͺĂŐĂŝŶƐƚͺ^ĐŝĞŶƟĮĐͺDŝƐĐŽŶĚƵĐƚ͘ĂƐƉ &ŽƌƌĞƉƌŝŶƚƐĐŽŶƚĂĐƚфŝŶĨŽΛƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƚĂdžĂ͘ŽƌŐх WƵďůŝƐŚĞƌͬ,ŽƐƚ WĂƌƚŶĞƌ dŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚTaxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 January 2016 | 8(1): 8333–8357 Avifauna of Chamba District, Himachal Pradesh, India with emphasis on Kalatop-Khajjiar Wildlife Sanctuary and its Communication surroundings ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Tariq Ahmed Shah 1, Vishal Ahuja 2, Martina Anandam 3 & Chelmala Srinivasulu 4 OPEN ACCESS 1,2,3 Field Research Division, Wildlife Information Liaison Development (WILD) Society, 96 Kumudham Nagar, Vilankurichi Road, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India 1,4 Natural History Museum and Wildlife -

Bhutan II Th Th 16 April to 5 May 2015 (20 Days)

Trip Report Bhutan II th th 16 April to 5 May 2015 (20 days) Ibisbill by Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by tour leader Wayne Jones Trip Report - RBT Bhutan II 2015 2 Our Bhutan tour kicked off at 350m above sea level in Samdrup Jongkhar, the border town close to Assam. The town's quiet gentility was quite a contrast to the hubbub of the Indian province in which we had just spent the last five days. Our arrival was in the late afternoon, so after settling into our hotel and meeting for dinner there wasn't much scope for birding. After supper, attempts to draw in a calling Collared Scops Owl were not entertained by the bird in question and a thunderstorm gently encouraged us to head to our rooms. This was to be the first of many encounters with rain in Bhutan! Crimson Sunbird by Wayne Jones The next morning we began our birding day with a walk along the main road on the outskirts of town while our bus went ahead to collect us later, the general modus operandi of birding in Bhutan. We glimpsed Red Junglefowl, Striated and Indian Pond Herons, Crested Honey Buzzard – one of which perched in a tree for good views, a Black Eagle cruising low over the treetops, Crested Goshawk, Green-billed Malkoha, House Swift, Wreathed Hornbill, Oriental Dollarbird, Lesser Yellownape, White-throated Kingfisher, Black-winged Cuckooshrike, Scarlet Minivet, Long-tailed Shrike, Ashy and Bronzed Drongos, Black-crested Bulbul, Red-rumped Swallow, Greenish Warbler, Rufescent Prinia, a gorgeous Asian Fairy-bluebird, a fleeting White-rumped Shama, common but beautiful Verditer Flycatcher, Black-backed Forktail, Blue Whistling Thrush, White- capped Redstart, Crimson Sunbird, Streaked Spiderhunter and Chestnut-tailed Starling. -

A Checklist of the Birds of Goa, India

BAIDYA & BHAGAT: Goa checklist 1 A checklist of the birds of Goa, India Pronoy Baidya & Mandar Bhagat Baidya, P., & Bhagat, M., 2018. A checklist of the birds of Goa, India. Indian BIRDS 14 (1): 1–31. Pronoy Baidya, TB-03, Center for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru 560012, Karnataka, India. And, Foundation for Environment Research and Conservation, C/o 407, III-A, Susheela Seawinds, Alto-Vaddem, Vasco-da-Gama 403802, Goa, India. E-mail: [email protected] [Corresponding author] [PB] Mandar Bhagat, ‘Madhumangal’, New Vaddem,Vasco-da-Gama 403802, Goa, India. E-mail: [email protected] [MB] Manuscript received on 15 November 2017. We dedicate this paper to Heinz Lainer, for his commitment to Goa’s Ornithology. Abstract An updated checklist of the birds of Goa, India, is presented below based upon a collation of supporting information from museum specimens, photographs, audio recordings of calls, and sight records with sufficient field notes. Goa has 473 species of birds of which 11 are endemic to the Western Ghats, 19 fall under various categories of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and 48 are listed in Schedule I Part (III) of The Indian Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972. 451 species have been accepted into the checklist based on specimens in various museums or on photographs, while 22 have been accepted based on sight record. A secondary list of unconfirmed records is also discussed in detail. Introduction that is about 125 km long. The southern portion of these ghats, Goa, India’s smallest state, sandwiched between the Arabian within Goa, juts out towards the Arabian Sea, at Cabo de Rama, Sea in the west and the Western Ghats in the east, is home to and then curves inland. -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

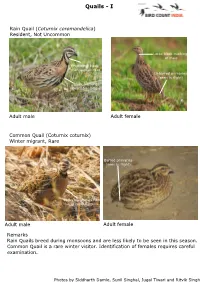

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Sri Lanka Ceylon Sojourn

Sri Lanka Ceylon Sojourn A Tropical Birding Set Departure January 20 – February 2, 2019 Guides: Ken Behrens & Saman Kumara Report and photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY The Indian Subcontinent is rich, both in human culture and history and in biological treasures. Sri Lanka is a large island at the southern tip of this region, lying a short distance from the Indian mainland. It contains a rich selection of the birds, mammals, and other wildlife of the subcontinent, which thrive in a selection of delightful protected areas; enough to thoroughly recommend it as a destination for a travelling birder. But even more alluringly, Sri Lanka is home to dozens of endemic birds – 33 given current Clements taxonomy, though this number is sure to continue to climb as distinctive subspecies are split as full species. Sri Lanka has decent infrastructure, excellent food, good lodges, and wonderfully kind and hospitable people. This short and sweet tour is equally attractive to those eager for their first taste of the Indian subcontinent, or to those who have travelled it extensively, and want to see the island’s endemic birds. As on all of our tours in recent years, we “cleaned up” on the endemics, enjoying great views of all 33 of them. This set of endemics includes a bunch of delightful birds, such as Sri Lanka Junglefowl, Sri Lanka Spurfowl, Serendib Scops-Owl, Chestnut-backed Owlet, Sri Lanka Hanging-Parrot, Red-faced Malkoha, Crimson-backed Woodpecker, Green-billed Coucal, Sri Sri Lanka: Ceylon Sojourn January 20-February 2, 2019 Lanka Blue Magpie, Sri Lanka (Scaly) and Spot-winged Thrushes, Yellow-eared Bulbul, and White-throated (Legge’s) Flowerpecker. -

Birding Hotspots

birding HOTSPOTS Dehradun | Surrounds ar anw ar Dhiman t Zanjale Madhuk Rajesh P Anan Ultramarine Flycatcher Egyptian Vulture Pin-tailed Green Pigeon a t t ar Dhiman Madhuk Suniti Bhushan Da Scarlet Minivet Yellow-bellied Fantail This booklet, the "Birding Hotspots of Dehradun and Surrounds", introduces 12 birding hotspots with details of their habitat, trails, birding specials by season, QR site locators and a map of the hotspots. © Uttarakhand Forest Department | Titli Trust ISBN: XXXXXX Citation: Sondhi, S. & S. B. Datta. (2018). Birding Hotspots of Dehradun and Surrounds. Published by Uttarakhand Forest Department & Titli Trust Front cover photograph: Kalij Pheasant, Gurinderjeet Singh Text Copyright : Sanjay Sondhi & Suniti Bhushan Datta Photograph Copyright: Respective photographers Map Credit: Suniti Bhushan Datta/ Google Earth Designed & Printed: Print Vision, Dehradun | [email protected] visit us at: www.printvisionindia.com About Birding Hotspots The hill state of Uttarakhand is a haven for birdwatching. The Updated Bibliography and Checklist of Birds of Uttarakhand by Dhananjai Mohan and Sanjay Sondhi in 2017 listed 710 bird species of the 1263 species listed from India (The India Checklist, Praveen et al., 2016). Dehradun and its surrounding areas has a checklist of 556 species possibly making it one of the richest cities in the world with respect to avian diversity! The Uttarakhand Spring Bird Festivals are held annually in Garhwal and Kumaon in Uttarakhand, to promote birdwatching in the state with the first th Ashish Kothari Dinesh Pundir edition of this festival having been held in 2014. This year, the 5 Uttarakhand Spring Bird Festival is being held at Thano Reserved Forest, Dehradun District and Jhilmil Jheel Conservation Reserve, Haridwar District. -

Birdlife of Pangot, Uttarakhand a Field Camp for BNHS-CEC Online Course Participants

Birdlife of Pangot, Uttarakhand A field camp for BNHS-CEC online course participants Pangot and Sattal, located in Nainital district, Uttarakhand, are not merely scenic but endowed with biodiversity-rich forests. The beautiful patches of forests are home to several bird species, and attract a continuous flow of birdwatchers. More than 200 bird species have been recorded in this area. The main attractions of Pangot are Cheer Pheasant, Koklass Pheasant and Kalij Pheasant. Others include Himalayan Vulture, Griffon Vulture, Himalayan Pied Woodpecker and Himalayan/Slaty-headed Parakeet. The Conservation Education Centre of BNHS, Mumbai centre, which conducts short-term online courses, organized a field camp at Pangot and Sattal between April 25–28, 2019 for Ornithology and Leadership and Biodiversity course participants, led by guide Mr. Hari Om and BNHS experts Nandkishor Dudhe and Omkar Joshi. The camp focused on the avian fauna of the region. As many as 163 species were recorded during the four days’ camp. Following important species were sighted during the field camp Sr. No Sattal Pangot Bird Checklist 1 Common Hill Partridge Arborophila torqueola 2 Black Francolin Francolinus francolinus 3 Cheer Pheasant Catreus wallichii 4 Kalij Pheasant Lophura leucomelanos 5 Koklass Pheasant Pucrasia macrolopha 6 Red Jungle fowl Gallus gallus 7 Rock Dove Columba livia 8 Oriental Turtle Dove Streptopelia orientalis [meena] 9 Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto 10 Spotted Dove Streptopelia chinensis 11 Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon Treron sphenurus