LIFE in IMPERFECT FORMS a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS by Maeve Kirk

In whatever wreckage remains Item Type Thesis Authors Kirk, Maeve Download date 24/09/2021 15:50:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6617 IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS By Maeve Kirk RECOMMENDED: Advisory Committee Chair Richard Carr, PhD Chair, Department of English --- ---^ APPROVED: ------ Todd Sherman, MFA IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts by Maeve Kirk, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2016 Abstract In Whatever Wreckage Remains is a collection of realistically styled short stories that examines both the danger and potential of change. These pieces are driven by the psychology of the men and woman roaming these pages, seeking to provide insight into the unique weight of their personal wreckage. From a woman craving motherhood who combs through forests searching for the unclaimed body of a runaway to a spitfire retiree’s struggle to accept her husband’s failing health, the individuals in these narratives are all navigating transitional spaces in their lives, often unwillingly. Along the way, they must balance the pressures of familial roles, romantic relationships, and personal histories while attempting to reshape their understanding of self. These stories explore the shifting landscape of identity, belonging, and the sometimes conflicting responsibilities we hold to others and to ourselves. v vi Dedication This manuscript is dedicated to my parents, who read me so many stories. vii viii -

Walls and Fences: a Journey Through History and Economics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Vernon, Victoria; Zimmermann, Klaus F. Working Paper Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics GLO Discussion Paper, No. 330 Provided in Cooperation with: Global Labor Organization (GLO) Suggested Citation: Vernon, Victoria; Zimmermann, Klaus F. (2019) : Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 330, Global Labor Organization (GLO), Essen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193640 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics* Victoria Vernon State University of New York and GLO; [email protected] Klaus F. Zimmermann UNU-MERIT, CEPR and GLO; [email protected] March 2019 Abstract Throughout history, border walls and fences have been built for defense, to claim land, to signal power, and to control migration. -

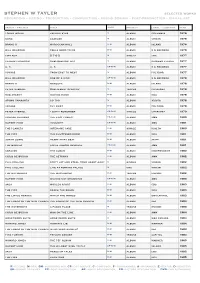

Stephen W Tayler Selected Works Recording - Mixing - Production - Composition - Sound Design - Post-Production - Visual Art

stephen w tayler selected works recording - mixing - production - composition - sound design - post-production - visual art artist - project title work project label - company year tommy bolin private eyes m album columbia 1976 gong gazeuse m album virgin 1976 brand x moroccan roll r-m album island 1976 bill bruford feels good to me r-m album e g records 1976 city boy 5 7 0 5 m single cbs 1977 claude francois quelquefois etc m album disques fleche 1977 u. k. u. k. cp-r-m album e g records 1977 voyage from east to west m album polydor 1977 bill bruford one of a kind cp-r-m album e g records 1978 brand x masques r-m album island 1978 peter gabriel 2nd album ‘scratch’ m tracks charisma 1978 rod argent moving home r-m album mca 1978 stomu yamashta go too m album arista 1978 voyage fly away r-m album polydor 1978 peter gabriel i don’t remember cp-r-m single charisma 1979 edward reekers the last forest cp-r-m album a&m 1980 rupert hine immunity cp-r-m album a&m 1981 the planets intensive care r-m single rialto 1980 the fixx the shuttered room r-m album mca 1981 jonah lewie heart skips beat r-m album stiff 1981 the models local and/or general cp-r-m album a&m 1981 caravan the album r-m album independent 1982 chris de burgh the getaway r-m album a&m 1982 phil collins don’t let her steal your heart away m single virgin 1982 phil collins live at perkins palace m vhs virgin 1982 the waterboys the waterboys r-m tracks ensign 1982 rupert hine waving not drowning cp-r-m album a&m 1983 saga worlds apart r-m album cbs 1983 the fixx reach the beach r-m album mca 1983 the little heroes watch the world r-m album emi/capitol 1983 the lords of the new church the lords of the new church r-m album irs 1983 the waterboys a pagan place m tracks ensign 1983 chris de burgh man on the line r-m album a&m 1984 honeymoon suite honeymoon suite m album wea canada 1984 howard jones human’s lib. -

Most Requested Songs of 2015

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2015 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 5 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 6 Williams, Pharrell Happy 7 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 8 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 9 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Mars, Bruno Marry You 16 Maroon 5 Sugar 17 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Legend, John All Of Me 20 B-52's Love Shack 21 Isley Brothers Shout 22 DJ Snake Feat. Lil Jon Turn Down For What 23 Outkast Hey Ya! 24 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 25 Beatles Twist And Shout 26 Pitbull Feat. Ke$Ha Timber 27 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 28 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 29 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 30 Trainor, Meghan All About That Bass 31 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 32 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 33 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 34 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 35 Bryan, Luke Country Girl (Shake It For Me) 36 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 37 Lmfao Feat. -

Extensions of Remarks

22152 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS SALUTE TO STEVE wrr'I'MAN In 1931 Wittman went to Oshkosh to take Many of the committee members were ac over the airport there and managed it until tive in the promotion. of ai:r s~ows her~ in his retirement this spring. the 1950's, and some, like Rutledge, are well HON. WILLIAM A. STEIGER S. J. Wittman was born in Byron April remembered for the job they did in promot OF WISCONSIN 5, 1904, and attended grade schools at Byron ing the 1953 City of Oshkosh centennial and Lomira. He was graduated from Fond celebration. · IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES du Lac High School. So, he has fl.rm roots When they speak, then, of drawing 100,000 Monday, August. 4, 1969 in Fond du Lac County and has many friends spectators to their show, or plan a banquet here. Certainly, many a local resident took with an attendance limited to 1,000 persons, Mr. STEIGER of Wisconsin. - Mr. to the air for the :first time in an open cock it seems to be no wishful thinking. Speaker, S. J. Wittman is one of tfie au pit, wooden "prop," strutted biplane with The renown of Wittman perhaps makes it thentic aviation leaders of our Nation. Steve Wittman at the controls. easier to put on a show of the magnitude the Steve has more hours in the air zoom Steve gained his national reputation pilot committee envisions. His friends in avia ing around the pylon in air races than ing aircraft in races all around the country. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Downloaded 17 July 2016

THE AUSTRALIAN WATER BUFFALO MANUAL Barry Lemcke Department of Primary Industry and Resources Northern Territory Government FOREWORD The Australian Water Buffalo Manual is a technical manual for the buffalo farming industry in Australia. Its author, Barry Lemcke, is a Northern Australian livestock scientist with over 42 years of experience, including a career focus on buffalo management research. The Manual reflects the extent of Barry’s knowledge and experience gained over his long career and is written in a style that makes the information accessible for all readers. It includes findings from research undertaken at Beatrice Hill Farm, Australia’s only buffalo research and development facility as well as from Barry’s travels related to the buffalo industry in numerous countries. The success of the dual purpose NT Riverine Buffalo derived from Beatrice Hill Farm, which now have progeny Australia-wide, can be largely attributed to Barry’s knowledge, dedication and persistence. John Harvey Managing Director Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED AACo Australian Agricultural Company ABARES Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences AI Artificial Insemination AMIEU Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union BEF Bovine Ephemeral Fever BHF Beatrice Hill Farm (Northern Territory Government Buffalo Research Facility) BTEC National Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign (Australia) cv Cultivar DM Dry Matter EEC European Economic Community ESCAS Exporter Supply -

Final Environmental Assessment for Reestablishment of Sonoran Pronghorn

Final Environmental Assessment for Reestablishment of Sonoran Pronghorn U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 6 October 2010 This page left blank intentionally 6 October 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION............................................ 1 1.1 Proposed Action.............................................................. 2 1.2 Project Need................................................................. 6 1.3 Background Information on Sonoran Pronghorn . 9 1.3.1 Taxonomy.............................................................. 9 1.3.2 Historic Distribution and Abundance......................................... 9 1.3.3 Current Distribution and Abundance........................................ 10 1.3.4 Life History............................................................ 12 1.3.5 Habitat................................................................ 13 1.3.6 Food and Water......................................................... 18 1.3.7 Home Range, Movement, and Habitat Area Requirements . 18 1.4 Project Purpose ............................................................. 19 1.5 Decision to be Made.......................................................... 19 1.6 Compliance with Laws, Regulations, and Plans . 19 1.7 Permitting Requirements and Authorizations Needed . 21 1.8 Scoping Summary............................................................ 21 1.8.1 Internal Agency Scoping.................................................. 21 1.8.2 Public Scoping ........................................................ -

Constructing a Simple Electric Predator Fence

Constructing a simple electric predator fence Joanne A. Siderius, Ph.D., Nelson, Areas E and F Bear Aware Community Coordinator [email protected] Disclaimer The instructions outlined here, and the materials suggested for use, have proven to produce a safe and effective electric predator fence. Neither the author, nor British Columbia Conservation Foundation’s Bear Aware Program, however, are responsible for any damages or injuries resulting during the construction or use of this fence. Constructing a simple electric predator fence Introduction These instructions will allow you to construct a simple, free-standing, six strand electrified fence that encloses the property (e.g., chicken coop, fruit tree or fruit orchard) that you wish to protect from a bear. You will end up with a fence of six live wires encircling your bear attractant, as opposed to a livestock fence that is often comprised of alternating live and ground wires. All wires should be live in a predator fence so that the bear will encounter a live wire no matter where it touches the fence. Constructing an electric fence to include an already constructed fence of wooden posts; the posts and structure of a chicken coop; t- posts and other options is also possible by modifying the materials and method described below. There are also situations and circumstances where using only four strands will suffice to discourage a bear. However, these instructions will get you started and have been proven to work best in deterring black and grizzly bears. www.bearaware.bc.ca Page 2 of 15 Constructing a simple electric predator fence Figure 1. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Opinion 2016

Final EA-09-098 Appendix A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Opinion United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office In Reply Refer to: 2800 Cottage Way, Suite W-2605 08ESMF00 Sacramento, California 9 5825-1846 2015-F-0008-R001 DEC 2 2 2016 Memorandum To: Rain Emerson, Supervisory Natural Resources Specialist, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Mid-Pacific Region, South-Central California Area Office, Fresno, California From jv\.~ or, Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office, Sacramento, California Subject: Reinitiation of Formal Consultation on the Contra Costa Water District Shortcut Pipeline Improvement Project near the Unincotporated Community of Clyde, Contra Costa County, California This memorandum is in response to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's (USBR) November 18, 2016, request for reinitiation of formal consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Set-vice (Set-vice) on the proposed Contra Costa Water District (CCWD) Shortcut Pipeline (SCPL) Improvement Project (proposed project) near the unincotporated community of Clyde in Contra Costa County, California. Your request was received by the Set-vice on November 23, 2016. USBR is requesting the reinitiation of formal consultation because CCWD is requesting (1) to add an additional staging area adjacent to Site 4, (2) to include improvements to an existing gravel road adjacent to Site 10, (3) to include annual mowing of the SCPL right-of-way (ROW) adjacent to the newly consttucted roads and repaired valves, and (4) to compensate at a 3:1 ratio for the permanent loss of habitat along the SCPL ROW instead of restoring habitat onsite and compensating at the 1:1 ratio for temporaty effects. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Chris De Burgh the Getaway Full Album Free Download

chris de burgh the getaway full album free download Chris De Burgh – The Ultimate Collection (2000) Chris De Burgh – The Ultimate Collection (2000) EAC Rip | 2xCD | FLAC Image + Cue + Log | Full Scans Included DVD-5 | VIDEO_TS | PAL 4:3 (720×576) VBR | Dolby AC-3 6ch & 2ch Total Size: 1.02 GB (CDs) + 2.94 GB (DVD) + 412 MB (Scans) | 3% RAR Recovery Label: A&M / Universal | EU | Cat#: 0600753212493 | Genre: Pop, Adult contemporary. The Ultimate Collection is a bountiful assortment of Chris de Burgh’s best material, up to and including songs from 2000’s Quiet Revolution album. The 38 tracks spotlight the best of de Burgh’s love songs, fairy tales, and quicker pieces, resulting in a delightful melange of this Argentinian-born’s music that spans nearly three decades. There’s an equal number of classics and newer songs, placing favorites such as “Don’t Pay the Ferryman,” “Lady in Red,” and “High on Emotion” between subtleties like “When I Think of You,” “Tender Hands,” and “Snows of New York.” The entrancing beauty of “A Spaceman Came Travelling,” which doubles as a popular Christmas tune, is a welcomed inclusion, as is the mysterious “Traveller” from 1980’s Eastern Wind and the carefree airiness of “Say Goodbye to It All” off of Into the Light. “Patricia the Stripper 2000” is novel, but the original would have fared much better. But surprises such as “Man on the Line,” “Ecstasy of Flight” and “Waiting for the Hurricane,” all of which weren’t huge successes, balance out the rest of the tracks quite nicely, showcasing de Burgh’s more animated efforts.