The Great Dismal Swamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

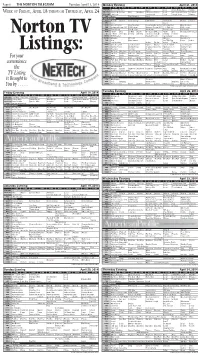

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

06 10-26-10 TV Guide.Indd 1 10/26/10 8:08:17 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, October 26, 2010 Monday Evening November 1, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , OCT . 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , NOV . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Rules Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC Chuck The Women of SNL Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX MLB Baseball Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention AMC Red Planet Rubicon Mad Men Volcano ANIM Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole River Monsters Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole CNN Parker Spitzer Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Wreck Wreck American Chopper American Chopper Wreck Wreck American Chopper DISN Den Brother Deck Hannah Hannah Deck Deck Hannah Hannah E! Kardashian True Hollywood Story Fashion Soup Pres Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 2010 Poker 2010 Poker 2010 Poker E:60 SportsNation FAM Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Spider-Man 3 Two Men Two Men Malcolm HGTV Property First House Designed House Hunters My First My First House Designed HIST Pawn Pawn American American Pawn Pawn Ancient Aliens Pawn Pawn LIFE Reba Reba Lying to Be Perfect How I Met How I Met The Fairy Jobmother Listings: MTV Jersey Shore World World World Buried World Buried Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife Chris Chris Lopez Lopez The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Gundam Gundam Darkness Darkness For your SPIKE Star Wars-Phantom Star Wars-Phantom Disorderly Con. -

On Reality Television During the Great Recession

Societies 2012, 2, 235–251; doi:10.3390/soc2040235 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article Working Stiff(s) on Reality Television during the Great Recession Sean Brayton Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2012; in revised form: 22 October 2012 / Accepted: 23 October 2012 / Published: 29 October 2012 Abstract: This essay traces some of the narratives and cultural politics of work on reality television after the economic crash of 2008. Specifically, it discusses the emergence of paid labor shows like Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal and a resurgent interest in working bodies at a time when the working class in the US seems all but consigned to the dustbin of history. As an implicit response to the crisis of masculinity during the Great Recession these programs present an imagined revival of manliness through the valorization of muscle work, which can be read in dialectical ways that pivot around the white male body in peril. In Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal, we find not only the return of labor but, moreover, the re-embodiment of value as loggers, roughnecks and miners risk both life and limb to reach company quotas. Paid labor shows, in other words, present a complicated popular pedagogy of late capitalism and the body, one that relies on anachronistic narratives of white masculinity in the workplace to provide an acute critique of expendability of the body and the hardships of physical labor. -

Today's Television

54 TV TUESDAY DECEMBER 29 2020 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak lHAD~UCflA UNFORTUNATE::!.'(, t;HE: with a laugh TIMr;;:AT!-UN OL-DME'1VUR ... OW NoTM1NG MUCM, How are dogs like cell JUST $OCllL 1>1STlNC1NG ,.. phones? 1>.NI> YoO? They both have collar id. wHaT kind of key can never unlock a door? A monkey. Snake Tales Swamp I OON'"r -.HIN< -rHl:S Today’s quiz IS GOING "l"O SE. .. 1. is a monteith a type of bowl, cape or curtain? 291220 2. The tangelo is a hybrid of which two fruits? f fq()J/ 3. What is a farthingale? T oday’S TeleViSion 4. Which country is the nine SeVen abc SbS Ten world’s second largest oil 6.00 Today. 6.00 Sunrise. 8.00 Pre-Game 6.00 Cook And The Chef. (R) 6.00 WorldWatch. 10.30 German 6.00 Left Off The Map. 6.30 producer? 9.00 Today Extra Show. 9.00 Cricket. Second Test. 6.25 Short Cuts To Glory. News. 11.00 Spanish News. 11.30 Everyday Gourmet. 7.00 Ent. Summer. (PG) Australia v India. Day 4. Morning (R) 7.00 News. 10.00 David Turkish News. 12.00 Arabic News Tonight. 7.30 Judge Judy. (PG) 11.30 Morning News. session. 11.00 The Lunch Break. Attenborough’s Tasmania. (R) F24. (France) 12.30 ABC America: 8.00 Bold. (PG) 8.30 Studio 5. What does the Latin 12.00 MOVIE: Miss Pettigrew 11.40 Cricket. Australia v India. 11.00 Gardening Australia. (R) World News Tonight. -

Thursday Morning, March 10

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 10 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Michelle Rodri- Live With Regis and Kelly Talent 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire guez. (N) (cc) (TV14) judge Jennifer Lopez. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 Early at 6 (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Aaron Eckhart; Avril Lavigne performs. (N) (cc) The Nate Berkus Show Do-it-your- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) self projects. (cc) (TVPG) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Search for the Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Blue Bar Pigeon. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) Better (cc) (TVPG) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid The Magic School Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Bus (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) George Lopez George Lopez The Young Icons Just Shoot Me My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Maury (cc) (TV14) Swift Justice- Swift Justice- The Steve Wilkos Show Abuse of a 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (TVG) (cc) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) Nancy Grace Nancy Grace young boy. -

Scenic Landforms of Virginia

Vol. 34 August 1988 No. 3 SCENIC LANDFORMS OF VIRGINIA Harry Webb . Virginia has a wide variety of scenic landforms, such State Highway, SR - State Road, GWNF.R(T) - George as mountains, waterfalls, gorges, islands, water and Washington National Forest Road (Trail), JNFR(T) - wind gaps, caves, valleys, hills, and cliffs. These land- Jefferson National Forest Road (Trail), BRPMP - Blue forms, some with interesting names such as Hanging Ridge Parkway mile post, and SNPMP - Shenandoah Rock, Devils Backbone, Striped Rock, and Lovers Leap, National Park mile post. range in elevation from Mt. Rogers at 5729 feet to As- This listing is primarily of those landforms named on sateague and Tangier islands near sea level. Two nat- topographic maps. It is hoped that the reader will advise ural lakes occur in Virginia, Mountain Lake in Giles the Division of other noteworthy landforms in the st& County and Lake Drummond in the City of Chesapeake. that are not mentioned. For those features on private Gaps through the mountains were important routes for land always obtain the owner's permission before vis- early settlers and positions for military movements dur- iting. Some particularly interesting features are de- ing the Civil War. Today, many gaps are still important scribed in more detail below. locations of roads and highways. For this report, landforms are listed alphabetically Dismal Swamp (see Chesapeake, City of) by county or city. Features along county lines are de- The Dismal Swamp, located in southeastern Virginia, scribed in only one county with references in other ap- is about 10 to 11 miles wide and 15 miles long, and propriate counties. -

1 Reworked Lithics in the Great Dismal Swamp Erin Livengood

Reworked Lithics in the Great Dismal Swamp Erin Livengood Honors Capstone Advisor: Dr. Dan Sayers Fall 2011 1 Introduction Archaeologists have long studied lithic technologies across the discipline and across the world. Created and used by all cultures, stone tools were made in many traditions using many varied techniques. Analyses of lithic tools can provide insights for archaeologists and can aid in interpretations of archaeological sites. In archaeological excavations, of both historical and prehistoric sites, lithics are commonly found artifacts. Due to the many toolmaking traditions utilized in lithic manufacture, oftentimes age of the lithic, geographic location of the lithic's creation, culture group that developed and utilized the tool and how it was used can be determined from the artifact. An analysis of material type can also be illuminative in lithic study; all of these aspects of study can lend ideas about past culture groups (Andrefsky 2009). The lithics included in the artifact assemblage from the Great Dismal Swamp include several different prehistoric technologies. Within this portion of the artifact assemblage, flakes (quartz, quartzite, rhyolite, and several kinds of unidentified lithic materials), projectile points, pebbles and other types of lithic debitage were discovered. This paper will analyze the reworked lithics included in this collection. These stone tools, namely the projectile points, discovered through archaeological excavations, shed light on the materiality of maroonage, particularly within the historic, social and cultural landscape of the Great Dismal Swamp. 2 Lithic Technologies Before the Time of Contact Many variations of lithic technologies existed in the United States before the time of contact. These stone tools are separated into distinct groupings based on characteristics of the tool. -

06 3-13-12 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 13, 2012 Monday Evening March 19, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , MARCH 16 THROUGH THURSDAY , MARCH 22 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC The Voice Smash Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Alcatraz Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention AMC Shawshank R. Shawshank R. ANIM North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic Rattlesnake Republic North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Sons of Guns American Chopper Sons of Guns DISN Doc McSt. Beverly Hills Shake It Austin ANT Farm Wizards Wizards E! Fashion Police Khloe Khloe True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Women's College Basketball Wm. Basketball Women's College Basketball FAM Pretty Little Liars Secret-Teen Pretty Little Liars The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Iron Man Iron Man HGTV Love It or List It House House House Hunters My House First House House HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn LIFE The Ugly Truth No Reservations The Ugly Truth Listings: MTV Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife George George '70s Show '70s Show Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI Being Human Being Human Lost Girl Being Human Lost Girl For your SPIKE Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die TBS Fam. -

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge Was Founded in 1974. the Refuge Consists of Over 112,000 Acres of Forests and Marshlands

Adaptation Strategies and Impacts of Climate Change on Bird Populations in The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge By, Karlie Pritchard 1. INTRODUCTION The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was founded in 1974. The refuge consists of over 112,000 acres of forests and marshlands. The Great Dismal Swamp provides habitat for 210 birds identified on the refuge (FWS, 2012). Effects of climate change such as impacts from greenhouse gases, extreme weather events, changes in vegetation, wildfires and biodiversity loss can play a negative role on the bird populations in the Great Dismal Swamp. As an indicator species, birds indicate overall health of an ecosystem and how well it is functioning through population trends (Hill, 2017). By analyzing prior data from the former refuge biologist, as well as monitoring current populations for specific bird species in the refuge we can determine a potential relation to climatic events. By evaluating the foresight of the refuge in regards to climate change we can develop adaptation and mitigation strategies for a stable bird population in the future. 2. HAZARDS TO BIRD POPULATIONS IN THE GREAT DISMAL SWAMP Hazards to bird populations in the Great Dismal Swamp generated by climate change include; extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts, floods, cold spells, precipitation, hurricanes and tornados. Other Hazards that may or may not be in relation to climate change affecting bird populations on the refuge are habitat loss, changes in vegetation, food chain disturbances, wildfires, water level and different management practices. Water management practices including rewetting the swamp can potentially disturb ground nesting and ground foraging birds if the ground is too wet or inundated by water, making their habitat less suitable (FWS, 2006). -

P32 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 24, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 04:15 Lip Sync Battle 01:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:20 Henry Hugglemonster 14:05 Second Wives Club 04:40 Ridiculousness Witch 23:35 The Hive 15:00 E! News 05:05 Disaster Date 01:40 Hank Zipzer 23:45 Loopdidoo 15:15 E! News: Daily Pop 05:30 Sweat Inc. 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 16:10 Keeping Up With The Kardashians 06:20 Life Or Debt 02:30 Binny And The Ghost 17:05 Live From The Red Carpet 00:15 Survivor 07:10 Disorderly Conduct: Video On 02:55 Hank Zipzer 19:00 E! News 02:00 Sharknado 2: The Second One Patrol 03:15 The Hive 20:00 Fashion Police 03:30 Fast & Furious 7 08:05 Disaster Date 03:20 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 21:00 Botched 06:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 08:30 Disaster Date Witch 22:00 Botched Nation 08:55 Ridiculousness 03:45 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:00 E! News 08:15 Bad Company 09:20 Workaholics Witch 00:20 Street Outlaws 23:15 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 10:15 Licence To Kill 09:45 Disaster Date 04:10 Hank Zipzer 01:10 Todd Sampson's Body Hack Henry 12:30 Fast & Furious 7 10:10 Ridiculousness 04:35 Binny And The Ghost 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 15:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 10:35 Impractical Jokers 05:00 Binny And The Ghost 02:50 Still Alive Nation 11:00 Hungry Investors 05:25 Hank Zipzer 03:40 Diesel Brothers 17:15 Run All Night 11:50 The Jim Gaffigan Show 05:45 The Hive 04:30 Storage Hunters UK 19:15 Golden Eye 12:15 Lip Sync Battle 05:50 The 7D 05:00 How Do They Do It? 21:30 San Andreas 12:40 Impractical Jokers 06:00 Jessie 05:30 How Do They Do It? 00:00 Diners, -

Great Dismal Swamp and Nansemond National Wildlife Refuges Over the Next 10-15 Years

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment NT OF E TH TM E Great Dismal Swamp nd Nansemond National Wildlife Refuges R I A N P T E E R D I . 3100 Desert Road O S R . Suffolk, VA 23434 U Great Dismal Swamp M 757/986 3706 A 49 R 18 757/986 2353 Fax CH 3, www.fws.gov/northeast/greatdismalswamp/ and Nansemond Federal Relay Service for the deaf and hard-of-hearing National Wildlife Refuges 1 800/877 8339 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Draft Comprehensive 1 800/344 WILD http://www.fws.gov Conservation Plan and March 2006 Environmental Assessment NT OF E TH TM E R I A N P T E E R D I . O S March 2006 R . U M A 49 RC H 3, 18 Lake Drummond USFWS This goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the principal federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fish and wildlife, plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. The Service manages the 96-million acre National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of 544 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. It also operates 65 national fish hatcheries and 78 ecological services field stations. The agency enforces federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally significant fisheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. -

R-5808 Re-Initiation Meeting Packet 2021-04-21.Pdf

Re-initiation Meeting TIP Project No. R-5808 WBS 46972.1.1 U.S. Route 158 Improvements From Acorn Hill Road (S.R. 1002) to the Pasquotank County Line Gates County April 2021 Purpose of Today’s Meeting: The purpose of this meeting is to re-acquaint the Merger Team members with the subject project and update them on coordination which has been completed since the April 2020 C.P. 3 and C.P. 4A meeting. 1. Project Background NCDOT proposes to improve approximately four miles of U.S. 158 in Gates County from Acorn Hill Road (S.R. 1002) to the Pasquotank County Line by widening the existing travel lanes and shoulders as well as stabilizing the side slopes. The project entered the Merger process in February 2019. Prior to the project being paused by NCDOT, the Merger Team concurred on Concurrence Points 1, 2, and 2A. Details regarding the study area, purpose and need of the project, three alternatives to be evaluated, and major hydraulic structures can be reviewed in Section 1.5 of the attached C.P. 3/C.P. 4A packet dated April 2020. 2. April 2020 C.P. 3/C.P. 4A Merger Meeting During the joint C.P. 3/C.P. 4A Merger Meeting in April 2020, NCDOT outlined the estimated impacts of the three alternatives, and recommended Alternative 1: widening U.S. 158 to the south along the entire project limits. The three alternatives, the assumed buffer areas used to estimate impacts, and the estimated impacts to environmental resources (including the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge) are outlined in detail in Section 2 of the attached C.P.