UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of St Albans and Mayoralty

A Brief History of St Albans and the Mayoralty History of St Albans Some of you may know that the area now known as The City and District of St Albans was originally occupied by an Iron Age tribe known as the Catuvellauni. Their capital was at Wheathampstead where it is suggested they were defeated under their leader Cassivellaunus by the Romans led by Julius Caesar in 54 BC. Within about 100 years, they had moved to the area which was to become Verulamium, the third largest Roman town in Britain. St Albans/Verulamium was located a day’s march from London (later a half day’s coach ride) so was an essential stopping point for travel to the north along Watling Street (A5). Alban, a Roman/British official who had converted to Christianity, was probably martyred in approx 250 AD. The site of his burial became a place of pilgrimage and was visited by Germanus of Auxerre in AD 429. He came to Britain at the request of Pope St. Celestine I. Later, a monastery was founded by Offa and dedicated to St Alban in AD 793 under its first Abbot Willegod. Subsequently, the Abbey was re-founded after the Norman Conquest by Paul de Caen, who had been appointed 14th Abbot of St Albans in 1077, and had the monastic church rebuilt according to the contemporary style. Robert the Mason was employed to build the new Abbey to dwarf, in size and magnificence, the earlier Saxon abbey. At the time it was the most contemporary Abbey in England. -

General Index

_......'.-r INDEX (a. : anchorite, anchorage; h. : hermit, hermitage)' t-:lg' Annors,enclose anchorites, 9r-4r,4r-3. - Ancren'Riwle,73, 7-1,^85,-?9-8-' I t2o-4t r3o-r' 136-8, Ae;*,;. of Gloucest"i, to3.- | rog' rro' rr4t r42, r77' - h. of Pontefract, 69-7o. I ^ -r4o, - z. Cressevill. I AnderseY,-h',16' (Glos), h', z8' earian IV, Pope, 23. i eriland 64,88' rrz' 165' Aelred of Rievaulx, St. 372., 97, r34; I Armyq Armitdge, 48, Rule of, 8o, 85, 96-7,- :.o3, tog, tzz,l - 184--6,.rgo-l' iii, tz6, .q;g:' a', 8t' ^ lArthu,r,.Bdmund,r44' e"rti"l1 df W6isinghaffi,24, n8-g. I Arundel, /'t - n. bf Farne,r33.- I .- ':.Ye"tbourne' z!-Jt ch' rx' a"fwi", tt. of Far"tli, 5, r29. I Asceticism,2, 4'7r 39t 4o' habergeon' rr8---zr A.tfr.it"fa, Oedituati, h.'3, +, :'67'8. I th, x-'16o, r78; ; Sh;p-h"'d,V"'t-;:"i"t-*^--- r18'r2o-r' 1eni,.,i. [ ]T"]:*'ll:16o, 1?ti;ll'z' Food' ei'i?uy,- ;::-{;;-;h,-' 176,a. Margaret1 . '?n, ^163, of (i.t 6y. AshPrington,89' I (B^ridgnotjh)1,1:: '^'-'Cfii"ft.*,Aldrin$;--(Susse*),Aldrington (Sussex), -s;. rector of,oI, a. atal Ilrrf,nera,fsslurr etnitatatton tD_rru6rrur\rrrt,.-.t 36' " IAttendants,z' companig?thi,p' efa*i"l n. of Malvern,zo. I erratey,Katherine, b. of LedbutY,74-5, tql' Alfred, King, 16, r48, 168. | . gil*i"", Fia"isiead,zr, I Augustine,St', 146-7' Alice, a. of".6r Hereford, TT:-!3-7. -

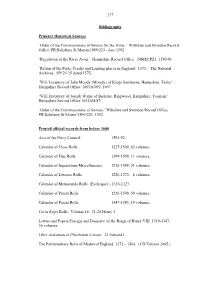

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

History of Lincolnshire Waterways

22 July 2005 The Sleaford Navigation Trust ….. … is a non-profit distributing company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (No 3294818) … has a Registered Office at 10 Chelmer Close, North Hykeham, Lincoln, LN6 8TH … is registered as a Charity (No 1060234) … has a web page: www.sleafordnavigation.co.uk Aims & Objectives of SNT The Trust aims to stimulate public interest and appreciation of the history, structure and beauty of the waterway known as the Slea, or the Sleaford Navigation. It aims to restore, improve, maintain and conserve the waterway in order to make it fully navigable. Furthermore it means to restore associated buildings and structures and to promote the use of the Sleaford Navigation by all appropriate kinds of waterborne traffic. In addition it wishes to promote the use of towpaths and adjoining footpaths for recreational activities. Articles and opinions in this newsletter are those of the authors concerned and do not necessarily reflect SNT policy or the opinion of the Editor. Printed by ‘Westgate Print’ of Sleaford 01529 415050 2 Editorial Welcome Enjoy your reading and I look forward to meeting many of you at the AGM. Nav house at agm Letter from mick handford re tokem Update on token Lots of copy this month so some news carried over until next edition – tokens, nav house description www.river-witham.co.uk Martin Noble Canoeists enjoying a sunny trip along the River Slea below Cogglesford in May Photo supplied by Norman Osborne 3 Chairman’s Report for July 2005 Chris Hayes The first highlight to report is the official opening of Navigation House on June 2nd. -

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain Michael Moises Garcia Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies August, 2010 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Michael Moises Garcia to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2010 The University of Leeds and Michael Moises Garcia iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I must thank my amazing wife Kat, without whom I would not have been able to accomplish this work. I am also grateful to the rest of my family: my mother Peggy, and my sisters Jolie, Julie and Joelle. Their encouragement was invaluable. No less important was the support from my supervisors, Ian Wood, Richard Morris, and Mary Swan, as well as my advising tutor, Roger Martlew. They have demonstrated remarkable patience and provided assistance above and beyond the call of duty. Many of my colleagues at the University of Leeds provided generous aid throughout the past few years. Among them I must especially thcmk Thom Gobbitt, Lauren Moreau, Zsuzsanna Papp Reed, Alex Domingue, Meritxell Perez-Martinez, Erin Thomas Daily, Mark Tizzoni, and all denizens of the Le Patourel room, past and present. -

London Metropolitan Archives Guild of Saint

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 GUILD OF SAINT ALBAN THE MARTYR A/GSA Reference Description Dates Minutes, accounts and attendance records A/GSA/001 1 volume containing:- Minutes of the Provost's Jun 1914-Jun Court, governing body of the Guild Jun 1914 1952 -Dec 1952; Minutes of General Meetings of the Guild Jun 1922-Jun 1952; Indexed A/GSA/002 Minute Book of the Provost's Court, indexed Dec 1952-Jun 1961 A/GSA/003 Envelope containing a letter from the Bishop of 25 Apr 1900 Southwark to M. S. Hall sanctioning the use of the Guild Collect with the Collect? enclosed A/GSA/003/001 Annual Statements of Accounts of the Guild, 1940 - 1959 with gaps 1 bundle A/GSA/004 Record of Attendances at Common Hall Jan 1926-Jun proceedings of the London Province of the 1960 Guild A/GSA/005 Minutes Book of Proceedings in Common Hall Feb 1939-Jun 1960 A/GSA/006 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the Dec 1898-Oct Divine 1902 A/GSA/007 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the Nov 1902-Aug Divine 1910 A/GSA/008 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the May 1910-Aug Divine 1915 A/GSA/009 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the Aug 1915-Aug Divine 1923 A/GSA/010 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the Aug 1923-Apr Divine 1929 A/GSA/011 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. John the Apr 1929-Oct Divine 1936 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 GUILD OF SAINT ALBAN THE MARTYR A/GSA Reference Description Dates A/GSA/012 Minute Book of the Brotherhood of St. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Factors Behind the Production of the Guthlac Roll (British Museum Harley Roll Y.6)

Forgery, Invention and Propaganda: Factors behind the Production of the Guthlac Roll (British Museum Harley Roll Y.6) Kimberly Kelly The Guthlac Roll, a scroll illustrating scenes from the rows of outline drawings depicting scenes from the First life of St. Guthlac (co. 674-714) ofCrowlan<!, was created in Book of Samuel, chapters I-VI. These drawings were exe England during the first two decades of the thirteenth cuted in ink and have been dated by George Warner ca. century. Most of the scenes chosen for illustration were 1300. According to Warner, these drawings are in no way · taken from the eighth-<:entury life of this saint, wrinen by related to the scenes of Guthlac's life. At least one piece of a scribe named Felix. As a result of this dependence, vellum is now missing from the Roll, leaving five pieces similarities between the text anil the Roll abound, but intact. The missing piece probably contained scenes of significant differences also exist. These divergences provide Guthlac's childhood and youth, including half of what is tantalizing clues to the factors and motivations behind the now the first roundel. As the pieces of veUum are all of production of the Guthlac Roll. different lengths, it is impossible to determine the length of The main purpose of this study will be to place the the missing section or the number of scenes it may have production of the Guthlac Roll within the context of local, contained. Furthermore, some type of introductory mate national and international events by focusing on the differ rial may have prefaced the scenes of Guthlac's life on other ences between Felix's text and the Roll and seeking to pieces of vellum now lost from the Roll. -

View Or Download

The Clergy of the Diocese every January 1 The Spouses of Diocesan Clergy every January 2 Church of the Redeemer, Mattituck every January 3 St.Mark's, Medford every January 4 Trinity Church, Northport every January 5 St.John's, Oakdale every January 6 St. Andrew's, Mastic Beach every January 7 St.Paul's, Patchogue every January 8 Christ Church, Port Jefferson every January 9 Church of the Atonement, Quogue every January 10 Grace Church, Riverhead every January 11 Staff & Board of Managers of Camp DeWolfe every January 12 Christ Church, Sag Harbor every January 13 St.James', St. James every January 14 St.Andrew's, Saltaire every January 15 St.Ann's, Sayville every January 16 St.Cuthbert's, Selden every January 17 The Diocesan Episcopal Church Women every January 18 Caroline Church, Setauket every January 19 St.Mary's, Shelter Island every January 20 St.Anselm's, Shoreham every January 21 St.Thomas of Canterbury, Smithtown every January 22 Hispanic Ministry Commission every January 23 Iglesia de la Santa Cruz, Brooklyn every January 24 St.John's, Southampton every January 25 All Souls' Church, Stony Brook every January 26 St.Mark's, Westhampton Beach every January 27 St.Andrew's, Yaphank every January 28 The Standing Committee of the Diocese every January 29 All Saints', Brooklyn every January 30 Church of the Ascension, Brooklyn every January 31 Calvary & St.Cyprian's, Brooklyn every February 1 Christ Church, Bay Ridge every February 2 Christ Church, Cobble Hill, Brooklyn every February 3 St. Mark's Day School, Brooklyn every February 4 -

Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire Ad 400-650

The Archaeological Journal Book Reviews BRITONS AND ANGLO-SAXONS: LINCOLNSHIRE AD 400-650. By Thomas Green. Pp. xvi and 320, Illus 48. The History of Lincolnshire Committee (Studies in the History of Lincolnshire, 3), 2012. Price: £17.95. ISBN 978 090266 825 6. Following the completion of the History of Lincolnshire Committee’s admirable twelve- volume history of the county, this book represents the third of a new series of more detailed studies of the region. Based upon his Ph D thesis, Thomas Green addresses the extent of Anglo-Saxon acculturation of Lincolnshire in the centuries following the withdrawal of the Roman legions, and the late survival of the British kingdom of Lindsey, centred on Lincoln. Despite Lincolnshire’s vulnerability to mass Germanic migration — according to traditional models — the substantial mid-fifth-century and later Anglo-Saxon cremation cemeteries, for which the county is famous, form a broad ring around Lincoln itself, which has little evidence for Anglo-Saxon activity until the mid-seventh century. Lincoln and its hinterland are instead characterized by British practice, particularly metalwork, which is extremely unusual for eastern England. The city is recorded as a metropolitan see in AD 314, and there is archaeological evidence for Romano-British continuity at the church of St Paul-in-the-Bail. Green favours a settlement model derived from Gildas, whereby the post-Roman British kings (‘tyrants’) of Lincoln directed and controlled Anglo-Saxon settlement in the county, potentially employing the migrants as mercenaries, although the argument that their major cremation cemeteries were located on strategic routes into the city is simplistically handled (pp. -

Read an Extract from Hertfordshire

Contents List of figures and tables vi Abbreviations ix Units of measurement and money ix Acknowledgements xi County map of Hertfordshire parishes xii 1 A county in context 1 2 Hertfordshire’s ‘champion’ landscapes 32 3 The landscape of east Hertfordshire 59 4 The landscape of west Hertfordshire 88 5 The landscape of south Hertfordshire 117 6 Woods, parks and pastures 144 7 Traditional buildings 178 8 Great houses and designed landscapes 207 9 Urban and industrial landscapes 239 10 Suburbs and New Towns, 1870–1970 268 Conclusion 297 Bibliography 301 Index 317 – 1 – A county in context Introduction This book is about the landscape of the county of Hertfordshire. It explains the historical processes that created the modern physical environment, concentrating on such matters as the form and location of villages, farms and hamlets, the character of fields, woods and commons, and the varied forms of churches, vernacular houses, and great houses with their associated parks and gardens. But we also use these features, in turn, as forms of historical evidence in their own right, to throw important new light on key debates in social, economic and environmental history. Our focus is not entirely on the rural landscape. Most Hertfordshire people, like the majority of their fellows elsewhere in the country, live in towns and suburbs, and these too – although often created relatively recently – are a part of the county’s historic landscape and have a story to tell. The purpose of this opening chapter is to set the scene, explaining some of the physical contexts and broad patterns of historical development which form the essential background to the more detailed studies presented in the chapters that follow.