Dumfries Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan November 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Proceedings

1 No. 2. m l>r^-r3 ef^ THE TRAiSSACTlUlMS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS ) ( \ )L'MI I'l I-- -I ! 1 l;l W I , I I l|[(ihttd|ft$tatg ^^ntiijuariaii ^(rddu. Sessions 1878-7" ml 1879-80. • I 1 I : 1 \ I \ I I H \ 1 h Mil 1 1 : 1 ^J^ll-*.- No. 2. THE TRANSACTIONS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY J^lttttal M%Ut^ 1 1 nt{ii«»t}»tt $^#a^ Sessions 1878-79 and 1879-80. (life; [The Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society was instituted on 20th November, 1862, and continued in a prosperous condition till May, 1875, when its meetings ceased. During this period Transactions and Proceedings were published on six occasions, the dates of publication being 1864, 1866, 1867, 1868, 1869, and 1871. The present Society was r -organised on 3d November, 187C, and the first portion of its Transactions and Proceedings was published in February, 1879.] PRINTED AT THE DUMFRIES AND GALLOWAY COURIER OFFICE. 18 8 1. OFFXCE-BEAHKRS AND COMMITTEE SEssionsr isso-si. Ipresl&ent. J. GIBSON STARKE, Esq., F.S.A. Scot., F.R.C.I., of Troqueer Holm. DicespreslDents. Sheriff HOPE, Dumfries. J. NEILSON, Esq. , Dumfries Academy. T. R. BRUCE, Esq. of Slogarie, New-Galloway. Secretarg. ROBERT SERVICE, Maxwelltown. assistant Secretary. JAMES LENNOX, Edenbank, Maxwelltown. tlrcasurcr. WILLIAM ADAMSON, Broom's Road, Dumfries. flftcmbers of Committee. A. B. CROilBIE, Architect, Dumfries. Dr GRIERSON, Thomhill. WILLIAM HALLIDAY, College Street, Maxwelltown. J. W. KERR, the Academy, Dumfries. WILLIAM LENNON, Brook Street, Dumfries JOHN MAXWELL, King Street, Maxwelltown. GEORGE ROBB, Rhynie House, Dumfries. -

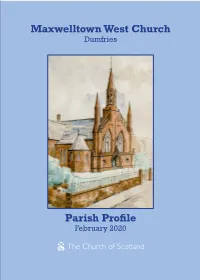

PARISH PROFILE LAYOUT Vfinal.Indd

Maxwelltown West Church Dumfries Parish Profile February 2020 MAXWELLTOWN WEST CHURCH - Our Mission - Maxwelltown West Church seeks to be a place of welcome to all in our parish; a centre of Christian worship and fellowship. We seek to provide a framework for family life and a place where young people may be nurtured in Christian values. SUNDAY SERVICES – 11 am CONTACTS During the Vacancy: Interim Moderator: Rev. Sally Russell (01556 503645) E: [email protected] Locum: David B Matheson (01387 252042) E: [email protected] Website: www.maxwelltownwest.org.uk #MaxWestChurch Tel: 01387 255900 Scottish Charity Reference: SC 015925; CCLI: 1194718 - CONTENTS - § Maxwelltown West Church: This is us § At the heart of our church : Our Values § What are we looking for? What are you looking for? § More of us § Our strengths and our weaknesses Statement from the Kirk Session § An active church § Let’s hear it from the congregation! § Our Parish § Dumfries & the wider area - MAXWELLTOWN WEST: THIS IS US - A BRIEF HISTORICAL SKETCH Our congregation began in 1843 as Maxwelltown Free Church, formed by ministers and members who left the parish churches in support of the principle of freedom to call a minister without the influence of a Patron. The first meeting of Maxwelltown Free Church was in the open air at the barnyard of Nithside. Such was the enthusiasm of the congregation that within six months a church had been built at North Laurieknowe. Part of that building stands today. On 8th July 1865, the foundation stone of the present building, to the design of Mr. -

Active Travel Dumfries Hospital Leaflet

QUARRY ROAD SCHOOL ROAD ROAD SCHOOL The smarter way to travel travel to way smarter The Dumfries Town 115 X74/74 CATHERINEFIELD ROAD Bus Routes 0256-17 Centre Inset 236 2 KNOWEHEADLocharbriggs RD September 2017 Primary Railway AUCHENCRIEFF RD School Holywood www.co-wheels.org.uk Station 236 1 246246 01387 Tel: Holywood L O A one. owning of hassle and costs the Primary Dumfries V STATION RD. E 336211 07788 Mob: School RS 81 River Nith Academy WALK without cars Co-wheels access can you so member a Locharbriggs Email: [email protected] Email: 3 Become work. and live people where near parked A76 A701 EDINBURGH RD ACADEMY STREET 504 cars with club car hour’ the by ‘pay a is Co-wheels 246 LOREBURNE STREET on: Davies Rhian Officer Travel Active our contact Or 1 Telephone: 01387 860805 or through Facebook through or 860805 01387 Telephone: MOSSDALE activetraveldumfries.wordpress.com HERRIES ANNAN RD. Lochthorn 1QB DG1 Library Heathhall visit: please walks, Ae Village, Parkgate, Village, Ae 3 504 Primary Café, and Shop Bike Ae Burns guided and sessions maintenance bike as such events AVE School WHITE SANDS C ST. MARY’S STREET BUCCLEUCH STREET F Statue don’t you when not transport to the new hospital, including active travel travel active including hospital, new the to transport 1 379/79/385 Dumfries to nearby shops Cycle HOODS LOANING Heathhall GT. KING ST. T. S LEAFIELD ROAD public and cycling walking, on information more For H and it want you when car A LIS NG B www.solwaycycles.co.uk Website: E Cinema DGOne X74/74 2 . -

Transactions and Journal of the Proceedings Of

No. 8. THE TRAXSACTIONS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS DUMFRIESSHIRE I GALLOWAY flatuml llistorii \ Aijtiparian Soeietij. SESSION 1891-92. PRIXTEI) AT THE STAXI)AR1> OFFICE, DUMFRIES. 1893. COTJZsrCIL, Sir JAMES CRICHTON BROWNE, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S. ^ice- Vvceti>c»jt«. Rev. WILLIAM ANDSON. THOMAS M'KIE, F.S.A., Advocate. GEORGE F. SCOTT-ELLIOT, M.A., B.Sc. JAMES G. HAMILTON STARKE, M.A., Advocate. §^ccvetavri. EDWARD J. CHINNOCK, M.A., LL.D., Fernbank, Maxwelltown. JOHN A. MOODIE, Solicitor, Bank of Scotland. Hbvaviaxj. JAMES LENNOX, F.S.A., Edenbank, Maxwelltown. ffiurrttor of JiUtaeitnt. JAMES DAVIDSON, Summerville, Maxwelltown. ffixtrcttov of gcrliarixtnt. GEORGE F. SCOTT-ELLIOT, F.L.S., F.R., Bot.Soe.Ed., Newton, assisted by the Misses HANNEY, Calder Bank, Maxwelltown. COti^ev plcmbei-a. JAMES BARBOUR. JOHN NEILSON, M.A. JOHN BROWN. GEORGE H. ROBB, M.A. THOMAS LAING. PHILIP SULLEY, F.R., Hi.st. Soc. ROBERT M'GLASHAN. JAMES S. THOMSON. ROBERT MURRAY. JAMES WATT. CO nSTTE nSTTS Secretary's Annual Report ... Treasurer's Annual Report Aitken's Theory of Dew. W. Andson Shortbread at the Lord's Supper. J. H. Thomson New and Rare Finds in 1891. G. F. Scott-Elliot Notes on Cowhill Herbarium. G.F.Scott-Elliot Fresh Water Fisheries. J. J. Armistead... Flora of Moffat District for 1891. J. T. Johnstone Franck's Tour in 1657. E.J. Chinnock ... Leach's Petrel. J. Corrie ... ... Cryptogamic Botanj^ of Moffat District. J. M'Andrew Study of Antiquity. P. Sulley Mound at Little liichon. F. R. Coles ^Meteorology of Dumfries for 1891. W. Andson... Location of Dumfriesshire Surnames. -

Police Amalgamation and Reform in Scotland

Edinburgh Research Explorer Police amalgamation and reform in Scotland Citation for published version: Davidson, N, Jackson, L & Smale, D 2016, 'Police amalgamation and reform in Scotland: The long twentieth century', Scottish Historical Review, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 88-111. https://doi.org/10.3366/shr.2016.0277 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/shr.2016.0277 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Scottish Historical Review General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 1 NEIL DAVIDSON, LOUISE A. JACKSON AND DAVID M. SMALE Police Amalgamation and Reform in Scotland: The Long Twentieth Century ABSTRACT This article examines shifting debates about police amalgamation and governance reform in Scotland since the mid-nineteenth century in the light of the creation of a single police service (Police Scotland) in 2013. From a proliferation of 89 separate police forces in 1859, the number had been reduced to 48 by 1949 and eight in 1975. -

School Exclusion Scheme

TILLEY AWARD 2003 Project Title School Exclusion Scheme Category Crime And Disorder Reduction Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary Endorsing Chief Officer(s) Superintendent Thomas Gordon Contact Details Name PC Andrew Hawes Position Crime Prevention Officer Address Dumfries & Galloway Constabulary, Divisional Headquarters, Loreburn Street, Dumfries, DG1 1HP. Telephone Number 01387 252112 Ext 65775 Fax Number 01387260556 EmaiI Address TILLEY AWARD 2003 SCHOOL EXCLUSION SCHEME Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary Contact: PC Andrew Hawes, Telephone: 01387 2521 12 Ext. 65775, E-mail: .4ndrcw. t Iau.es:i.rl,ciu~n----, ti-iesnrldgall o\vay.p~~~~~di~c~~!~ CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 .I Description of location 1.2 Defining the problem (Scanning) 2. ANALYSIS 2.1 Underlying Causes 2.2 Victim 2.3 Locations 2.4 Offenders 3. RESPONSE 3.1 Partnerships 3.2 Actions 4. ASSESSMENT 4.1 Outcome of project 4.2 Progress since implementation 4.3 Future 6. APPENDICES Appendix 1 - Vandalism Report - Dumfries Schools I 999 - 2002 Appendix 2 - "We Need Your Help" flyer Appendix 3 - Education Committee Paper on School SecurityiVandaiism (3rd December 2002) Appendix 4 - Letter to Headteachers from Education Department TILLEY AWARD 2003 SCHOOL EXCLUSION SCHEME Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary Contact: PC Andrew Hawes, Telephone: 01387 252112 Ext 65775, E-mail: Andreit .Hau~es+;dumfi-~&~sandgallo wa~;i?nuylj ce. tk Nature of probIem addressed: Combnt irzstanc@sof vanrlafism nnd anti-social behaviour at Schools in the town of Durnfries. Dumfries has a population of about 45+000residents. In the south east area there is a residential area known as Georgetown and Calside. Under-age drinking: vandalism, anti-social behaviour, littering has been seen by the local community, Local Authority, Police and other interested parties as being an increasing problem in the area. -

Burns Chronicle 1995

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1995 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Mrs Helen Morrison The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE INCORPORATING "THE BURNSIAN" BICENTENARY of DEATH DECEMBER 1995 VOL. 4 (NEW SERIES) NUMBER 3 BURNS COUNTRY TOURING SOVEREIGN Chauffeur Drive The story of Scotland's National Poet Robert Burns is woven into the Ayrshire countryside which he knew so well. Burns Country holds a warm welcome for visitors, and at SOVEREIGN we offer a touring service tailored to your particular requirements. Whether a Burns expert, an enthusiast, or just curious to find out more about the legend - allow us to help make your visit a memorable one. Please call or write for our brochure and tariff SOVEREIGN Chauffeur Drive, Carrick Cottage, 15 Main Street, Dundonald, Ayrshire. KA2 9HF, Scotland, UK. Telephone: 44 1563850971 Fax: 44 1563850660 (UK Code 01563) Other Services: Airport/ Hotel transfers, Evening Hire, Executive Travel, Touring throughout Scotland and Northern England, SPecial Interest Tours (Castles, Historic Homes) . Members - AYRSHIRE TOURIST BOARD Partners - Catherine and William McKinlay BURNS CHRONICLE INCORPORATING "THE BURNSIAN" Contents DECEMBER 1995 Dumfries Commemoration .................................... 5 Burns's Neighbours in Dumfries ......................... 15 NUMBER 3 How We Licked 'Em ........ .. ....... .. ...... .. ................... 24 The Cheltenham Connection ........................ ..... .. 28 VOL. 5 Robert Burns -A Reverie and a Reminiscence ... 32 My Sketchbook ...................................................... 34 Coilsfield "The Castle 0' Montgomerie" ............ 36 The Passions of Robert Burns .............. ..... .... ... .... 43 Roger Quin, Scotland's Tramp Poet ........ -

Maxwelltown West Church, Dumfries

MAXWELLTOWN WEST CHURCH, DUMFRIES www.maxwelltownwest.org.uk SUNDAY SERVICES: 11.00am COMMUNION SERVICE: 11th September at 11.00am. SUNDAY SCHOOL (J-Max & K-Max): 11.00am during term time. CRECHE is available during the morning service every Sunday. Tots ‘n’ Tunes (for babies and toddlers) meets in the Committee Room on the 3rd Thursday of each month at 10.00am. ********** ********** ********** ********** ********** ********** MINISTER: Rev. Gordon M.A. Savage, M.A., B.D. Maxwelltown West Manse, 11 Laurieknowe, Dumfries DG2 7AH During Mr. Savage’s phased return to work, the Interim Moderator is Rev. Donald Campbell CHILDREN’S & FAMILY WORKER: Mrs. Rachel Lyagoba ********** ********** ********** ********** ********** ********** Congregational Office Bearers SESSION CLERK: Mr. T Bryden CLERK TO DEACONS’ COURT: Mrs. E Riddick ORGANIST: Mr. S Crosbie TREASURER: Mr. D McNay CHURCH OFFICER: Mr. R Wilson ‘ACTING’ FABRIC CONVENER: Mr. D Miller EDITOR OF ‘CONTACT’: Mrs. F Saddington CONGREGATIONAL REGISTER Baptism 19th June: Adam John McNay Marriages 28th May (at the Crichton Memorial Church): M S Duggan to K L Macleod 9th July (at the Crichton Memorial Church): A J MacDonald to C G S Abel Deaths 9th June: Mrs. Norah Kirkpatrick New Members by Transference Mrs. E Adams Rev. E Mack Ms. J Hastie Mr. B Peacham Mr. C Hunter Transference Certificates Issued Rev. C and Mrs. M Sutherland Mr. A Wallace MAXWELLTOWN WEST MISSION STATEMENT Maxwelltown West Church seeks to be a place of welcome to all in our parish; a centre of Christian worship and fellowship. We seek to provide a framework for family life and a place where young people may be nurtured in Christian values. -

Lochfield Road Report to Board Of

Dumfries & Galloway Health Board Pharmacy Practices Committee Minutes of the meeting of the Pharmacy Practices Committee held on Tuesday, 11 December 2012 in the Empire Suite, within the Park House Suite, Cairndale Hotel, English Street, Dumfries, DG1 2DF PRESENT COMMITTEE Mr I Hyslop (Chairman) Board Appointees Pharmacists Mr W Beaugié Mr G Loughran (non-contractor) Mrs V Jardine-Patterson Mrs D Martyniuk (contractor) Mr G Makins Mr G Winter (contractor) Attending NHS Dumfries & Galloway Mrs L Bunney Administrator Head of Primary Care Development Mrs S M Burns Administrator PCD Administration Manager Mrs J Jones Minute Secretary PCD Administration Assistant Mrs D McCulloch Minute Secretary Executive Assistant to Medical Director Applicant Mrs J Weir Ahmed, Holm Pharm Ltd Applicant Ms M Grierson Assisting (Friend) Interested Parties Mr C Tait Boots UK Ltd (Presenter) Ms T Wilson Boots UK Ltd (Assisting) Mr J Currie Dalhart Pharmacy Ltd T/as Wm Murray Chemist (Presenter) Mr T Arnott Lloyds Pharmacy Ltd (Presenter) Ms J McDougall Lloyds Pharmcy Ltd (Assisting) Mr M Rodden AMR Drug Co Ltd T/as Northern Chemist (Presenter) Mrs A M Rodden AMR Drug Co Ltd T/as Northern Chemist (Assisting) 1 APPLICATION FOR INCLUSION IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL LIST Application by Mrs J Weir Ahmed of Holm Pharm Ltd (“the Applicant”), for inclusion in the Pharmaceutical List of Dumfries & Galloway Health Board (“the Board”) in respect of a proposed new pharmacy at Lochfield Road Primary Care Centre, 12-28 Lochfield Road, Dumfries, DG2 9BH Hearing of Application: Tuesday, 11 December 2012. Decision of the Pharmacy Practices Committee: The Committee refused the application. -

Family Tree Maker 2005

Descendants of James Fergusson 1 James Fergusson b: 1770 d: in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland .. +Margaret Moffat b: 1770 d: in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland ....... 2 Alexander Fergusson b: 1794 in Glencairn Parish, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 19 May 1862 in Ayr Street, Moniaive, Glencairn, Scotland ........... +Isabella Wilson b: 1790 in Glencairn Parish, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 08 Nov 1862 in Ayr Street, Moniaive, Glencain, Scotland ................. 3 James Fergusson b: 1826 in Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland ..................... +Maryann unknown b: 1827 in Ireland ................. *2nd Wife of James Fergusson: ..................... +Mary Dickie b: 1826 m: 13 Feb 1842 in Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 26 May 1846 in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland ................. 3 Anne Fergusson b: 1827 in Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland ..................... +James Murray b: 1828 in Dumfries, Dumfriesshire, Scotland m: 17 Oct 1851 in Moniaive, Free Church, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland ................. 3 Thomas Fergusson b: 12 Jan 1827 in Twomerkland, Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 23 Dec 1900 in 24, Terregles Street, Troqueer, Maxwelltown, Kirkcudbright, Scotland ..................... +Jane McCulloch b: 28 Apr 1834 in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland m: 29 Jan 1861 in Ayr Street, Moniaive, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 05 May 1891 in 24, Terregles Street, Troqueer, Maxwelltown, Kirkcudbright, Scotland ................. 3 Margaret Moffatt Fergusson b: 1832 in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 20 Jan 1905 in Afton Bridgend, New Cumnock, Ayr, Scotland ..................... +Hugh Gallochar b: 1832 in Kilmarnock, Ayr, Scotland m: 01 Dec 1854 in Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 11 Oct 1885 in Connelburn Gatehouse, New Cumnock, Ayr, Scotland ....... 2 Janet Fergusson b: 1802 in Glencairn Parish, Dumfriesshire, Scotland d: 28 Jul 1858 in Ayr Street, Moniaive, Glencairn, Dumfriesshire, Scotland .......... -

Journal of the Proceedings

: / THE TMNSACTIONS AND JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE DUMFRIESSHIRE & GALLOIFAY NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY. Session 1867-68. D U iTT R I E S PRINTED BY W. R. M'DIARMID AND CO. 187 1. : THE TRANSACTIONS AND -JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE DUMFRIESSHIRE & GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY. Session 1867-68. D U M F "H n 8 PRINTED BY W. R MTDIARMID AND CO. 18 7 1. CONTENTS. Page. Jodenaij op the Proceedings 1 Absteact op Treasdeee's Accounts 10 Secretaet's Report for Session 1868-9 H St. Ninian, the Apostle op Galloway. By Jas. Starke, F.S.A. Scot. 17 On the Meaning op the Names op Places in the Neighbour' 24 HOOD which AEE OP CELTIC ORIGIN. By M. MORIAETY . Notice op the Scottish Service Book op 1637. By Jas. Starke, F.S.A. Scot 29 History op a Ceichton Boulder. By J. Gilchrist, M.D., Medical Superintendent, Crichton Royal Institution .... 34 Minerals lately pound In Dumpriesshieb and Galloway, not hitherto noticed as occurring in the Localities. By Mr Dudgeon . 38 Note op Rare Bied3 that have occurred in Dumpeiesshire and Galloway during the past year. By the President . 39 Notes on Birds and their Habits, as observed at Ashbank, Maxwelltown. By T. Coreie 39 Notes on Lepidoftera. By Wm. Lennon 47 JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE Dumfriesshire & Galloway Natural History and Antiquaria?i Society. October 30i/i, 1867. At a Meeting of Committee held in tlieir apartment in the Dumfries and Galloway Club Rooms, Sir W. JAR DINE, Bart., in the Chair, Dr Dickson having intimated his resignation of the Sec- retaryship of the Society, having accepted a situation in the Island of Mauritius, it was proposed by him and seconded that Mr M'Diarmid should be requested to accept of this office. -

Continuity and Change in Scotland's Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions

Études écossaises 18 | 2016 Écosse : migrations et frontières Civic Borders and Imagined Communities: Continuity and Change in Scotland’s Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions and Structures—from 19th-Century “General Police” to 21st-Century “Community Empowerment” Frontières civiques et communautés imaginées : continuité et changement dans les frontières municipales, juridictions et structures écossaises entre le XIXe et le XXIe siècles Michael Pugh Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/1055 DOI: 10.4000/etudesecossaises.1055 ISSN: 1969-6337 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version Date of publication: 25 April 2016 Number of pages: 29-49 ISBN: 978-2-84310-324-7 ISSN: 1240-1439 Electronic reference Michael Pugh, “Civic Borders and Imagined Communities: Continuity and Change in Scotland’s Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions and Structures—from 19th-Century “General Police” to 21st- Century “Community Empowerment””, Études écossaises [Online], 18 | 2016, Online since 01 January 2017, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/ 1055 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.1055 © Études écossaises Michael Pugh University of the West of Scotland Civic Borders and Imagined Communities: Continuity and Change in Scotland’s Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions and Structures — from 19th-Century “General Police” to 21st-Century “Community Empowerment” Much recent scrutiny has been given to the significance of the external border between Scotland and the rest of the continuing United Kingdom, given the debates surrounding the 2014 Scottish Referendum and its aftermath (see for example Black, 2014). However, Scotland’s internal borders in the form of local authority boundaries, and the often-fuzzy politico-legal line between the responsibilities and powers of Scotland’s national (devolved) government and its 32 unitary local authorities merit attention also (see maps at Scottish Government undated, and Undis- covered Scotland, undated — hyperlinks in bibliography).