Continuity and Change in Scotland's Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Burghs of Ayrshire

8 9 The Burghs of Ayrshire Apart from the Stewarts, who flourished in the genealogical as well as material sense, these early families died out quickly, their lands and offices being carried over by heiresses to their husbands' GEOEGE S. PEYDE, M.A., Ph.D. lines. The de Morville possessions came, by way of Alan Professor of Scottish History, Glasgow University FitzEoland of Galloway, to be divided between Balliols, Comyns and de la Zouches ; while the lordship was claimed in thirds by THE HISTORIC BACKGROUND absentees,® the actual lands were in the hands of many small proprietors. The Steward, overlord of Kyle-stewart, was regarded Apart from their purely local interest, the Ayrshire burghs as a Renfrewshire baron. Thus Robert de Bruce, father of the may be studied with profit for their national or " institutional " future king and Earl of Carrick by marriage, has been called the significance, i The general course of burghal development in only Ayrshire noble alive in 1290.' Scotland shows that the terms " royal burgh" (1401) and " burgh-in-barony " (1450) are of late occurrence and represent a form of differentiation that was wholly absent in earlier times. ^ PRBSTWICK Economic privileges—extending even to the grant of trade- monopoly areas—were for long conferred freely and indifferently The oldest burgh in the shire is Prestwick, which is mentioned upon burghs holding from king, bishop, abbot, earl or baron. as burgo meo in Walter FitzAlan's charter, dated 1165-73, to the Discrimination between classes of burghs began to take shape in abbey of Paisley. * It was, therefore, like Renfrew, a baronial the second half of the fourteeth century, after the summoning of burgh, dependent upon the Steward of Scotland ; unlike Renfrew, burgesses to Parliament (in the years 1357-66 or possibly earlier) * however, it did not, on the elevation of the Stewarts to the throne, and the grant to the " free burghs " of special rights in foreign improve in status and it never (to use the later term) became a trade (1364).* Between 1450 and 1560 some 88 charter-grant.? royal burgh. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

The Story of the Barony of Gorbals

DA flTO.CS 07 1 a31 1880072327^436 |Uj UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH [y The Library uA dS/0 G5 1^7 Ur<U» JOHN, 1861-192b» THE 5T0RY UP THE bAkONY OF viGRdALS* Date due ^. ^. k ^'^ ^ r^: b ••' * • ^y/i'^ THE STORY OF THE BARONY OF GORBALS Arms of Viscount Belhaven, carved on the wall of Gorbals Chapel, and erroneously called the Arms of Gorbals. Frontispiece. (See page 21) THE STORY OP"' THE BARONY OF GORBALS BY JOHN ORD illustrations PAISLEY: ALEXANDER GARDNER ^ttbliBhtt bB S^vvointmmt to tht IttU Qnun Victoria 1919 LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & CO., LMD. PRINTED BY ALEXANDER GARDNER, PAISLEY. THr LflJRARY PREFACE. Few words are required to introduce this little work to the public of Glasgow. Suffice it to say that on several occasions during the past four years I was invited and did deliver lectures on "Old Gorbals"" to a number of public bodies, among others being the Gorbals Ward Committee, the Old Glasgow Club, and Educational Guilds in connection with the Kinningpark Co-operative Society. The princi- pal matter contained in these lectures I have arranged, edited, and now issue in book form. While engaged collecting materials for the lectures, I discovered that a number of errors had crept into previous publications relating to Old Gorbals. For example, some writers seemed to have entertained the idea that there was only one George Elphinston rented or possessed the lands of Gorbals, whereas there were three of the name, all in direct succession. M'Ure and other historians, failing to distinguish the difference between a Barony and a Burgh of Barony, state that Gorbals was erected into a Burgh of Barony in 1595. -

Journal of Proceedings

1 No. 2. m l>r^-r3 ef^ THE TRAiSSACTlUlMS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS ) ( \ )L'MI I'l I-- -I ! 1 l;l W I , I I l|[(ihttd|ft$tatg ^^ntiijuariaii ^(rddu. Sessions 1878-7" ml 1879-80. • I 1 I : 1 \ I \ I I H \ 1 h Mil 1 1 : 1 ^J^ll-*.- No. 2. THE TRANSACTIONS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY J^lttttal M%Ut^ 1 1 nt{ii«»t}»tt $^#a^ Sessions 1878-79 and 1879-80. (life; [The Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society was instituted on 20th November, 1862, and continued in a prosperous condition till May, 1875, when its meetings ceased. During this period Transactions and Proceedings were published on six occasions, the dates of publication being 1864, 1866, 1867, 1868, 1869, and 1871. The present Society was r -organised on 3d November, 187C, and the first portion of its Transactions and Proceedings was published in February, 1879.] PRINTED AT THE DUMFRIES AND GALLOWAY COURIER OFFICE. 18 8 1. OFFXCE-BEAHKRS AND COMMITTEE SEssionsr isso-si. Ipresl&ent. J. GIBSON STARKE, Esq., F.S.A. Scot., F.R.C.I., of Troqueer Holm. DicespreslDents. Sheriff HOPE, Dumfries. J. NEILSON, Esq. , Dumfries Academy. T. R. BRUCE, Esq. of Slogarie, New-Galloway. Secretarg. ROBERT SERVICE, Maxwelltown. assistant Secretary. JAMES LENNOX, Edenbank, Maxwelltown. tlrcasurcr. WILLIAM ADAMSON, Broom's Road, Dumfries. flftcmbers of Committee. A. B. CROilBIE, Architect, Dumfries. Dr GRIERSON, Thomhill. WILLIAM HALLIDAY, College Street, Maxwelltown. J. W. KERR, the Academy, Dumfries. WILLIAM LENNON, Brook Street, Dumfries JOHN MAXWELL, King Street, Maxwelltown. GEORGE ROBB, Rhynie House, Dumfries. -

Newmilns & Greenholm Community Action Plan 2021-2026 Profile

Newmilns & Greenholm Community Action Plan 2021-2026 Profile 1. Brief Description and History 1.1 Early History Evidence of early habitation can be found across The Valley, with the earliest sites dating from around 2000 BC. To the east of Loudoun Gowf Course, evidence has been found of the existence of a Neolithic stone circle and a Neolithic burial mound lies underneath the approach to the seventh green. A site in Henryton uncovered a Neolith barrow containing stone axes (c. 1500 BC) and a Bronze Age cairn dating from about 1000 BC (the cairn itself contains cists which are thought to have been made by bronze weapons or tools). Following this early period, from around AD 200 evidence exists of not only a Roman camp at Loudoun Hill, but also a Roman road running through The Valley to the coast at Ayr. The camp was uncovered through quarry work taking place south of Loudoun Hill but tragically much of this evidence has been lost. According to local workmen, many of the uncovered remains & artefacts were taken with the rest of the quarried materials to be used in road construction projects. Typically, little is known of The Valley's history during the Dark Ages, but it seems likely that an important battle was fought around AD 575 at the Glen Water. In addition, given the strong strategic importance of Newmilns' position as a suitable fording place and a bottleneck on one of Scotland's main east-west trade routes, it is not unlikely that other battles and skirmishes occurred during this period. -

Example Page from Scottish Census, 1881 RETURN of ALL the PERSONS WHO SLEPT OR ABODE in THIS INSTITUTION on the NIGHT of SUNDAY, APRIL 3Rd 1881

The undermentioned Houses are situate within the Boundaries of the Civil Parish of Quoad Sacra Parish School Board District Parliamentary Burgh Royal Burgh of Police Burgh of Town of Village or Hamlet of of Newington of Edinburgh of Edinburgh St. Cuthbert HOUSES I U Whether Rooms with No. of one or more Schedule Road, Street, or Name and Surname Relation to Condition Age Rank, Profession or Occupation Where born (1) Deaf-and-Dumb windows &c. and No. or of each Person Head of as to (2) Blind Name of B Family Marriage (last Birthday) (3) Imbecile or Idiot House (4) Lunatic 4 7, Hamilton St I William Morrison Head Mar. 31 Spirit Dealer Edinburghsire, St. Cuthbert 7 Mary J. Do. Wife Mar. 29 Fifeshire, Cupar Ellen Do. Daur. 7 mo. Lanarkshire, Glasgow Elizabeth Morrison Mother W. 58 Annuitant Do. Do. Imbecile Anne Fox Serv. Unm. 28 General Serv. Perthshire, Errol Catherine Doyle Serv. Unm. 24 Barmaid Ireland 5 8, Do. I Peter Newton Head Mar. 39 Grocer (Master, employing 2 men) Kirkcudbrightshire, Minnigaff 4 Emma Do. Wife Mar. 36 Do. Kirkbean William Do. Son 12 Scholar Forfarshire, Dundee Ronsetta Do. Daur. 9 Do. Do. Do. Deaf and Dumb from Birth George Duff Shopman Unm. 19 Grocer’s Shopman Stirlingshire, Falkirk Jane Cock Serv. Unm. 22 General Serv. England 6 8, Do. I James F. Bruce Head Mar. 41 Banker’s Clerk Bannfshire, Rathhuen 3 Harriet Do. Wife Mar. 29 Do. Do. Sophia White Serv. Unm. 16 General Serv. Ayrshire, Kilmarnock 7 Walter Campbell Lodger Unm. 23 Ship Carpenter (out of employ) Renfrewshire, Greenock 1 9, Do. -

Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 63) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 36) STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty December 1974 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 36p net Cmnd. 5792 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of pro- moting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Cooke, Chairman. Mr. Claud Bicknell, O.B.E. Mr. Aubrey L. Diamond. Mr. Derek Hodgson, Q.C. Mr. Norman S. Marsh, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr. J. M. Cartwright Sharp and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Hunter, Chairman. Mr. A. E. Anton, C.B.E. Mr. R. B. Jack. Professor T. B. Smith, Q.C. Mr. Ewan Stewart, M.C., Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr. J. B. Allan and its offices are at the Old College, University of Edinburgh, South Bridge, Edinburgh, EH8 9BD. _. ii , THE LAW COMMISSION and THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals)Bill prepared under section 3( l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965. -- To the Right Honourable the Lord Elwyn-Jones, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable Ronald King Murray, Q.C., M.P., Her Majesty’s Advocate.* We have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 to this Report and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

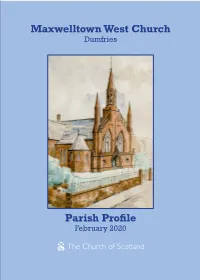

PARISH PROFILE LAYOUT Vfinal.Indd

Maxwelltown West Church Dumfries Parish Profile February 2020 MAXWELLTOWN WEST CHURCH - Our Mission - Maxwelltown West Church seeks to be a place of welcome to all in our parish; a centre of Christian worship and fellowship. We seek to provide a framework for family life and a place where young people may be nurtured in Christian values. SUNDAY SERVICES – 11 am CONTACTS During the Vacancy: Interim Moderator: Rev. Sally Russell (01556 503645) E: [email protected] Locum: David B Matheson (01387 252042) E: [email protected] Website: www.maxwelltownwest.org.uk #MaxWestChurch Tel: 01387 255900 Scottish Charity Reference: SC 015925; CCLI: 1194718 - CONTENTS - § Maxwelltown West Church: This is us § At the heart of our church : Our Values § What are we looking for? What are you looking for? § More of us § Our strengths and our weaknesses Statement from the Kirk Session § An active church § Let’s hear it from the congregation! § Our Parish § Dumfries & the wider area - MAXWELLTOWN WEST: THIS IS US - A BRIEF HISTORICAL SKETCH Our congregation began in 1843 as Maxwelltown Free Church, formed by ministers and members who left the parish churches in support of the principle of freedom to call a minister without the influence of a Patron. The first meeting of Maxwelltown Free Church was in the open air at the barnyard of Nithside. Such was the enthusiasm of the congregation that within six months a church had been built at North Laurieknowe. Part of that building stands today. On 8th July 1865, the foundation stone of the present building, to the design of Mr. -

Active Travel Dumfries Hospital Leaflet

QUARRY ROAD SCHOOL ROAD ROAD SCHOOL The smarter way to travel travel to way smarter The Dumfries Town 115 X74/74 CATHERINEFIELD ROAD Bus Routes 0256-17 Centre Inset 236 2 KNOWEHEADLocharbriggs RD September 2017 Primary Railway AUCHENCRIEFF RD School Holywood www.co-wheels.org.uk Station 236 1 246246 01387 Tel: Holywood L O A one. owning of hassle and costs the Primary Dumfries V STATION RD. E 336211 07788 Mob: School RS 81 River Nith Academy WALK without cars Co-wheels access can you so member a Locharbriggs Email: [email protected] Email: 3 Become work. and live people where near parked A76 A701 EDINBURGH RD ACADEMY STREET 504 cars with club car hour’ the by ‘pay a is Co-wheels 246 LOREBURNE STREET on: Davies Rhian Officer Travel Active our contact Or 1 Telephone: 01387 860805 or through Facebook through or 860805 01387 Telephone: MOSSDALE activetraveldumfries.wordpress.com HERRIES ANNAN RD. Lochthorn 1QB DG1 Library Heathhall visit: please walks, Ae Village, Parkgate, Village, Ae 3 504 Primary Café, and Shop Bike Ae Burns guided and sessions maintenance bike as such events AVE School WHITE SANDS C ST. MARY’S STREET BUCCLEUCH STREET F Statue don’t you when not transport to the new hospital, including active travel travel active including hospital, new the to transport 1 379/79/385 Dumfries to nearby shops Cycle HOODS LOANING Heathhall GT. KING ST. T. S LEAFIELD ROAD public and cycling walking, on information more For H and it want you when car A LIS NG B www.solwaycycles.co.uk Website: E Cinema DGOne X74/74 2 . -

Transactions and Journal of the Proceedings Of

No. 8. THE TRAXSACTIONS JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS DUMFRIESSHIRE I GALLOWAY flatuml llistorii \ Aijtiparian Soeietij. SESSION 1891-92. PRIXTEI) AT THE STAXI)AR1> OFFICE, DUMFRIES. 1893. COTJZsrCIL, Sir JAMES CRICHTON BROWNE, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S. ^ice- Vvceti>c»jt«. Rev. WILLIAM ANDSON. THOMAS M'KIE, F.S.A., Advocate. GEORGE F. SCOTT-ELLIOT, M.A., B.Sc. JAMES G. HAMILTON STARKE, M.A., Advocate. §^ccvetavri. EDWARD J. CHINNOCK, M.A., LL.D., Fernbank, Maxwelltown. JOHN A. MOODIE, Solicitor, Bank of Scotland. Hbvaviaxj. JAMES LENNOX, F.S.A., Edenbank, Maxwelltown. ffiurrttor of JiUtaeitnt. JAMES DAVIDSON, Summerville, Maxwelltown. ffixtrcttov of gcrliarixtnt. GEORGE F. SCOTT-ELLIOT, F.L.S., F.R., Bot.Soe.Ed., Newton, assisted by the Misses HANNEY, Calder Bank, Maxwelltown. COti^ev plcmbei-a. JAMES BARBOUR. JOHN NEILSON, M.A. JOHN BROWN. GEORGE H. ROBB, M.A. THOMAS LAING. PHILIP SULLEY, F.R., Hi.st. Soc. ROBERT M'GLASHAN. JAMES S. THOMSON. ROBERT MURRAY. JAMES WATT. CO nSTTE nSTTS Secretary's Annual Report ... Treasurer's Annual Report Aitken's Theory of Dew. W. Andson Shortbread at the Lord's Supper. J. H. Thomson New and Rare Finds in 1891. G. F. Scott-Elliot Notes on Cowhill Herbarium. G.F.Scott-Elliot Fresh Water Fisheries. J. J. Armistead... Flora of Moffat District for 1891. J. T. Johnstone Franck's Tour in 1657. E.J. Chinnock ... Leach's Petrel. J. Corrie ... ... Cryptogamic Botanj^ of Moffat District. J. M'Andrew Study of Antiquity. P. Sulley Mound at Little liichon. F. R. Coles ^Meteorology of Dumfries for 1891. W. Andson... Location of Dumfriesshire Surnames. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. We are informed that in assuming this device no special allusion was intended by the authorities of Aberchirder ; we should therefore conjecture that the charge was obtained by some course of syllogistic reasoning such as — burghs have crosses : this is a burgh ; therefore it ought to have a cross. -

126613718.23.Pdf

SC^.SHS./3] PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME LIII THE COURT BOOK OF THE BURGH OF KIRKINTILLOCH 1658—1694 1963 THE COURT BOOK OF THE BURGH OF KIRKINTILLOCH 1658—1694 Edited by GEORGE S. PRYDE, M.A., Ph.D. EDINBURGH Printed by T. and A. Constable Ltd. Printers to the University of Edinburgh for the Scottish History Society 1963 I 20 OEg V1963 Printed in Great Britain PREFATORY NOTE Professor George S. Pryde died suddenly in Cornwall on 6 May 1961, when he had almost completed the editing of this volume. Although a graduate of St. Andrews, his academic career, after a period of study at Yale, was spent in the University of Glasgow. Successively Assistant, Lecturer and Reader in the Department of Scottish History and Literature, he succeeded to the Chair in 1957. His publications in the fields of both medieval and modern Scottish history are well known, but special mention must be made here of his edition of the Ayr Burgh Accounts, published by the Scottish History Society in 1937. He became a member of the Society in 1934 and joined the Council in 1948. He was at the time of his death Chairman of Council, after holding that office for only a few months. Tributes have been paid elsewhere to his gifts as an his- torian and as a teacher but his colleagues on the Council of the Society will recall also the cheerful friendliness which he brought to its meetings. Professor Pryde had prepared for print almost the whole of the text of the court book and his introduction was complete to 1660.