Artists and Institutions: Institution for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore Biennale 2016 Artists and Artwork Highlights ‘An Atlas of Mirrors’ Explained Through 9 Curatorial Sub-Themes Singapore, 22 September 2016 – The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) today revealed a list of 62 artists and art collectives and selected artwork highlights of the Singapore Biennale 2016 (SB2016), one of Asia’s most exciting contemporary visual art exhibitions. Titled An Atlas of Mirrors, SB2016 draws on diverse artistic viewpoints that trace the migratory and intertwining relationships within the region, and reflect on shared histories and current realities with East and South Asia. SB2016 will present 60 artworks that respond to An Atlas of Mirrors, including 49 newly commissioned and adapted artworks. The SB2016 artworks, spanning various mediums, will be clustered around nine sub-themes and presented across seven venues – Singapore Art Museum and SAM at 8Q, Asian Civilisations Museum, de Suantio Gallery at SMU, National Museum of Singapore, Stamford Green, and Peranakan Museum. The full artist list can be found in Annex A. SB2016 Artists In addition to the 30 artists already announced, SB2016 will include Chou Shih Hsiung, Debbie Ding, Faizal Hamdan, Abeer Gupta, Subodh Gupta, Gregory Halili, Agan Harahap, Kentaro Hiroki, Htein Lin, Jiao Xingtao, Sanjay Kak, Marine Ky, H.H. Lim, Lim Soo Ngee, Made Djirna, Made Wianta, Perception3, Niranjan Rajah, S. Chandrasekaran, Sharmiza Abu Hassan, Nilima Sheikh, Praneet Soi, Adeela Suleman, Melati Suryodarmo, Nobuaki Takekawa, Jack Tan, Tan Zi Hao, Ryan Villamael, Wen Pulin, Xiao Lu, Zang Honghua, and Zulkifle Mahmod. SB2016 artists are from 18 countries and territories in Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia. -

JEREMY SHARMA Born 1977, Singapore

JEREMY SHARMA Born 1977, Singapore EDUCATION 2006 Master of Art (Fine Art), LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore 2003 Bachelor of Art (Fine Art) with High Distinction, LASALLE College of the Arts (RMIT), Singapore RESIDENCIES 2016 Stelva Artist in Residence, Italy 2015 NTU Centre for Contemporary Arts, Singapore 2014 Temenggong Artist in Residence with Fundación Sebastián, Mexico City 2008 Artist Residency & Exchange Program (REAP) by Artesan Gallery Singapore, Manila, The Philippines 2007 Royal Over-Seas League (ROSL), Travel Scholarship, Hospitalfield, Arbroath, Scotland, United Kingdom 2004 Studio 106, Former Residential-Studio of the late Cultural Medallion Dr. Ng Eng Teng, Joo Chiat Place, Managed by LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, Singapore AWARDS AND PRIZES 2013 RPF Grant, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore 2013 Creation Grant, National Arts Council, Singapore 2007 Royal Over-Seas League (ROSL) Travel Scholarship 2005 LASALLE-SIA Scholarship 2005 JCCI Arts Award, Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Recipient (with KYTV) 2003 Phillip Morris Singapore Arts Award, Honorable Mention 2003 Studio 106, Residency Award 2002 The Lee Foundation Study Grant, Singapore 2000 Action for Aids Award, First Prize (Open Category), Singapore 1999 The Della Butcher Award, Presented by The Rotary Club of Singapore, winner COLLECTIONS Singapore Art Museum Ngee Ann Kongsi, Singapore SOCIÈTÉ GÉNÈRALE The Westin, Singapore One Farrer Private Limited NUS Business School, Singapore Prime Partners COMMISSIONS Slow Fury, Asian Film Archives, -

Singapore: Sensory Perceptions 5/5/14 11:08 AM

Singapore: Sensory perceptions 5/5/14 11:08 AM 11:07AM Monday May 05, 2014 Do you know more about a story? Real Estate Cars Jobs Dating Newsletters Fairfax Media Network Singapore: Sensory perceptions May 4, 2014 Read later Nina Karnikowski Travel Writer View more articles from Nina Karnikowski Follow Nina on Twitter Follow Nina on Google+ submit to reddit Email article Print Brave new world: Art Seasons gallery. The island city is giving Hong Kong a shake as Asia's arts hub, writes Nina Karnikowski. Think of Singapore and behemoth shopping malls, the Merlion, Singapore Slings and a distinct lack of chewing gum will probably all come to mind. But art galleries? Maybe not so much. That's all changing, however, thanks to a state-led effort to promote the "Lion City" as one of Asia's largest cultural and artistic hubs, with the Singaporean government pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars a year into the city's arts scene. http://www.watoday.com.au/travel/singapore-sensory-perceptions-20140501-37j3w.html Page 1 of 6 Singapore: Sensory perceptions 5/5/14 11:08 AM The Rendezvous Hotel. Singapore already boasts more than 50 contemporary art galleries, including the newly opened Centre for Contemporary Art and the Singapore Art Museum, and hosts world-class art events including the recent Singapore Biennale and Art Stage Singapore, south-east Asia's largest art fair. And with both the Singapore Pinacotheque de Paris (the first Asian outpost of Paris' largest private art museum) and the National Art Gallery (which will exhibit the world's biggest public collection of modern Southeast Asian and Singaporean art) scheduled to open in 2015, the city is giving Hong Kong a run for its money in the race to become Asia's arts hub. -

Singapore Pavilion Opens at the Venice Biennale 2011

Jun 03, 2011 17:13 +08 Singapore Pavilion Opens at the Venice Biennale 2011 Singapore artist Ho Tzu Nyen presents “The Cloud of Unknowing”, a video art installation at the Singapore Pavilion of the 54th Venice Biennale. The Pavilion will be officially opened on Wednesday, 1 June at the Salone di Ss. Filippo e Giacomo del Museo Diocesano di Venezia, Italyby the Chairman of the National Arts Council (NAC) Singapore, Mr Edmund Cheng. Mr Khor Kok Wah, Deputy Chief Executive Officer, NAC, said, “I am pleased that Singapore continues to be a part of the Venice Biennale even as we strive to establish similar international platforms like the recently concluded Singapore Biennale, and Art Stage Singapore in January this year. Such international platforms are vital for the creative connections that are forged across borders and cultures.” The theme of this year’s Venice Biennale, “ILLUMInations”, calls for a reflection upon the conventions through which contemporary art is viewed. Ho’s audio-visual installation explores art history, looking at forms of illumination, luminance and of being transported by clouds. His piece portrays the sensory experience of eight different characters occupying apartments in a deserted, low-income public housing block in Singapore, each of whom has an encounter with a cloud which alternates between appearing as a figure, and a vaporous mist. “The Cloud of Unknowing” is commissioned and presented by The National Arts Council Singapore and supported by the Lee Foundation and Mori Art Museum. The curator of the pavilion, June Yap, is an independent curator based in Singapore. She has curated with the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (LASALLE) and the Singapore Art Museum. -

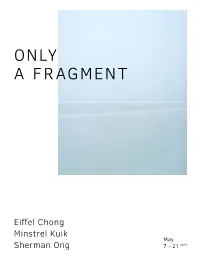

Only a Fragment

ONLY A FRAGMENT Eiffel Chong Minstrel Kuik May Sherman Ong 7 – 21 2015 Only a Fragment “A photograph Nowadays, we are constantly bombarded by the photo- and the strict visual structure, Eiffel is able to conjure a is only a graphed image, scattered everywhere in the urban breath of associations such as Color Field paintings to landscape, seducing us with their auratic quality, at the minimal abstraction. As in his other previous series, Eiffel fragment, same time attempting to sell something, while in cyber- considers the abstract concepts of life and death through an and with the space, the digital image mutate, grow, change via digital economical visual language, highlighting banal details such passage of time tools or disintegrate via sharing and usage. Furthermore, as soft clouds in the sky and the horizon line into delicate its moorings the act of taking a photograph has become an innate gesture textures. Furthermore their uniformed stillness links them to most people equipped with smartphones and mobile as one, and one is again reminded that all seas are actually come unstuck. digital devices. These photos captured anywhere using part of the same mass of water. Finally, there is a sense It drifts a mobile device could mean something for a moment of calmness fabricated by the images as one is given an away into a either as a way to document vital information or freeze opportunity to view nature before the intervention of man. soft abstract meaningful moments, but usually in time end up as hopeless digital relics forgotten in the phone's memory. -

The Unofficial Art Stage Trail, Arts News & Top Stories

The unofficial Art Stage trail, Arts News & Top Stories - The Straits Times 29/1/19, 952 PM Ex-insurance agent jailed for Oon to leave Sports Hub Enroll Your Child Today! sending threatening messages to clients who The Learning Lab cancelled policies THE STRAITS TIMES LIFESTYLESponsored Recommended by The unofficial Art Stage trail A 4.5m-long painting by French artist Vincent Corpet, which will be on display at Mazel Galerie's booth at The ARTery pop-up showcase at Marina Bay Sands. PHOTOS: MAZEL GALERIE, OPERA GALLERY ! PUBLISHED JAN 22, 2019, 5:00 AM SGT Many stranded galleries and artists have found alternative platforms to show their works after the cancellation of Art Stage Singapore. Called off nine days before its public opening, Art Stage was to have run at the Marina Bay Sands Expo and Convention Centre from Friday to Sunday. Here are 10 locations where you can view the artworks Toh Wen Li " (mailto:[email protected]) 1 THE ARTERY A new pop-up showcase called The ARTery will feature at least 14 Singapore and international galleries which had signed up for Art Stage Singapore. It is organised by non-profit group Art Outreach with help from the National Arts Council, Singapore Tourism Board and Economic Development Board, and support from Marina Bay Sands. Some of the galleries include Linda Gallery, based in Singapore, Jakarta and Beijing, which will showcase copper and brass works by Indonesian sculptor Nyoman Nuarta; and Tanya Baxter Contemporary, based in London and Hong Kong, which will display graffiti artist Banksy's original Bomb Love (2003) and British artist Tracey Emin's limited-edition lithographs, among other works. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Artist Biography

Artist Donna ONG ⺩美清 Born Singapore Works Singapore Artist Biography __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Education 2011 - 2012 MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore 2003 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK 1999 B.Sc. Architecture Bartlett Centre, University College London (UCL), UK __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Selected Exhibitions 2017 Singapore: Inside Out Sydney, The Old Clare Hotel, Sydney, Australia After Utopia: Revisiting the Ideal in Asian Contemporary Art, Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, Adelaide, Australia The Tree as An Art Object, Wälderhaus Museum, Hamburg, Germany Art Stage Jakarta, FOST Gallery, Indonesia Art Stage Singapore, FOST Gallery, Singapore 2016 The Sharing Game: Exchange in Culture and Society, Kulturesymposium Weimar 2016, Galerie Eigenheim, Weimar, Germany For An Image, Faster Than Light, Yinchuan Biennale 2016, MoCA Yinchuan, China Five Trees Make A Forest, NUS Museum, Singapore* My Forest Has No Name, FOST Gallery, Singapore* 2015 After Utopia, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore The Mechanical Corps, Hartware MedienKunstVerein, Dortmund, Germany Prudential Eye Awards, ArtScience Museum, Singapore Prudential Singapore Eye, ArtScience Museum, Singapore 2014 Da Vinci: Shaping the Future, ArtScience Museum, Singapore Modern Love, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, Singapore Bright S’pore(s), Primo Marella Gallery, -

Artist Biography

Artist Grace TAN 陈 斯恩 Born 1979 Country Malaysia/Singapore Medium Mixed media Artist Biography __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Education 1999 Diploma with Merit in Apparel Design and Merchandising, Temasek Polytechnic Design School, Singapore __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Selected Exhibitions 2015 Echoes of Anticipation, FOST Gallery, Singapore the truth of matter, FOST Gallery, Singapore* The Measure of Your Dwelling: Singapore as Unhomed, IFA Gallery, Berlin, Germany Potong Ice Cream $2, LATENT SPACES, Booth H1A at Art Stage, Singapore These Sacred Things, Jendela, Esplanade Mall, Singapore 2014 Weaving Viewpoint, Space Cottonseed, Singapore Echoes of Anticipation, FOST Gallery, Singapore Market Forces 2014, Erasure: From Conceptualism to Abstraction, Osage Art Foundation and City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2013 MM, Final presentation for the Associate Artist Research Programme, The Substation Gallery, Singapore* 2011 Splendid Memory Still Flows Back Into Cosmos… Wow Really, School of the Arts Gallery, School of the Arts, Singapore Inter_Play, Jointly presented by Spiro Grace Art Rooms and Chan Hampe Galleries, Brisbane, Asutralia and Singapore respectively Miniature, Spiro Grace Art Rooms, Brisbane, Australia 2010 Floating Worlds, Chan Hampe Galleries, Singapore One Part II, Unlimited Designing / Asia-Pacific Design Triennial, Spiro Grace Art Rooms, Brisbane, Australia SOLa, -

Es with KL Will Meet Again to Continue Discus- Here

Headline Singapore Art Week Whimsical works Publication THE STRAITS TIMES Date 2019-01-15 Section LIFE Page Number A1 & D1 & D2 Article Size 3696.757 cm2 Journalist [email protected] (Akshita Nanda) TUESDAY JANUARY 15, 2019 SINCE 1845 AVE $ 43104 | THE STRAITS TIMES | TUESDAY, JANUARY 15, 2019 INSPIRED BY SUNGEI BULOH D Unusual writing residencies Home 32 Top of the News Life Overcoming WP aims for Oeat across Singapore Add D4&5 the odds Maths one-third of works at for O levels scripts Parliament A7 S’pore Art go Sport missing Week True greatness D1&2 can’t be hurried B1&2 C9 Top of the News IHiS disciplines sta over cyber breach A6 • Opinion Ensuring peace of mindSingapore over Arthospital Week bills A16 Unique and intimate art experi- 590,000 viewers, according to the ences feature prominently in this arts council. but it was overshadowed by other year’s Singapore Art Week (SAW) – Ms Linda de Mello, director, issues that subsequently arose. They the biggest visual arts celebration sector development (visual arts), S’pore to discuss issues with KL will meet again to continue discus- here. National Arts Council, said: “We’re sions, he said. Apart from mega light shows very encouraged that the visual arts WhimsicalThe transport ministers from both organised by National Gallery Singa- community continues to be excited countries have also agreed to meet pore and big-ticket contemporary by Singapore Art Week – over the later this month for further discus- art fairs such as Art Stage Singapore past few years, we’ve increasingly calmly, but will guard its turf: Vivian sions on the airspace dispute. -

Singapore Art Week: the Last Word – Paul Carter Robinson

Singapore Art Week: The Last Word – Paul Carter Robinson artlyst.com/features/singapore-art-week-last-word-paul-carter-robinson/ Singapore is a vibrant hub at the best of times, but it doubles up as a key global centre for contemporary art, as the world focuses on Singapore Art Week. Over the period of seven days the city hosts a major international art fair, Art Stage Singapore as well the many public and commercial art displays. The city welcomes both fine and Urban art, showcasing some of the best art in the region. Singapore is polite and welcoming. It is a thoroughly safe place to visit with true multi- cultural harmony – PCR Day one: I visited the Esplanade a massive complex like London’s Southbank which features everything from opera, theatre to art exhibitions. This year the stylishly designed centre exhibited art by the Vietnamese artist UuDam Tran Nguyen. The work consists of a large-scale (forgive the pun) inflated installation titled ‘Serpent’s Tails’. The work was accompanied by a video in the carpark, which was an adventure to discover. Mash-Up Collective Gillman Barracks Singapore Art Week Day two: we visited the fantastic Gillman Barracks a former British military outpost from the colonial era. This is a massive ‘art park’ with galleries, studios and outdoor art installations. Of special note, the D/SINI commissioned Gillman Pavillion by the Mash-Up Collective, an 1/6 art and fashion merger and Catch Yourself If You Can, Lugas Syllabus’, 2017, a fibreglass dragon creature which plays with iconography from pop culture. -

EKO NUGROHO Born 1977, Yogyakarta

EKO NUGROHO Born 1977, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia EDUCATION 1993 – 97 School for Fine Arts (SMSR) Yogyakarta 1997 – 2006 Painting Department, Indonesian Art Institute, Yogyakarta AWARDS 2017 Indonesia’s Influential Person in Creative Industry (Visual Art) by Idea Fest x Samsung Galaxy Note 8 2013 Icon of the Year 2013 in Art and Culture, Gatra Magazine, Indonesia 2008 Academy Art Award for Emerging Artist, Indonesian Institute of Arts 2005 Best Artist of the Year, Tempo Magazine, Indonesia RESIDENCIES 2017 Shangri La Center for Islamic Art, Culture & Design, Honolulu, Hawai 2012 Singapore Tyler Print Institute, Singapore 2011 ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany 2011 SAM Art Projects, Villa Raffet in Paris, France 2009 Veduta-Biennale de Lyon, France 2008 Heden, Den Haag, The Netherlands 2008 Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, New Orleans, Lousiana, USA 2008 Singapore National Museum, Singapore 2007 Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland 2006 Gallery of Modern Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia 2006 Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan 2005 Artoteek Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands 2005 Rimbun Dahan, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2005 Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany 2004 Amsterdam Graphics Atelier (AGA), Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2004 Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Japan COLLECTIONS Akili Museum of Art, Jakarta, Indonesia. Arario Collection, Cheonan, South Korea Art Gallery of South Australia, North Terrace, Adelaide, Australia Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sidney, Australia Artnow, International A3 Collection, San Fransisco, USA Artoteek Den Haag/HEDEN , The Hague, Netherland. Ark Gallerie, Jakarta, Indonesia. Asia Society Museum, New York, USA Cemeti Art House, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.