Glazed Concrete and Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arne Jacobsen Arne Jacobsen

ARNEARNE JJAACOBSENCOBSEN THETHE TTONGUEONGUE THE TONGUE We fell truly, madly, deeply in love with this chair We admit it. We just fell in love. When the opportunity arose to take Arne Jacobsen’s Tongue chair under our wing at HOWE, we couldn’t resist. Does it sound crazy? That’s fine. We’re happy to say that we’re more than a little mad about this delightful chair. 4 5 A lost classic returns You see, the cutely named Tongue is a Danish design classic that went missing. Designed right after the Ant chair in 1955, the Tongue was always one of Arne Jacobsen’s favourites but never really found a home. Now the Tongue is back. 6 7 A visionary designer Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971) is one of the best known designers of the 20th century. An extraordinary man of immense vision, Arne Jacobsen occupies the pinnacle of modern Danish design. His work epitomises Danish modernism and is held permanently by museums, prized by collectors, and employed throughout the world in home, work and educational environments. 8 9 Arne Jacobsen’s childhood Arne Jacobsen was born in Copenhagen in 1902. He was an only child in a family where the father was a wholesaler and the mother was one of the first women in Denmark to be trained in banking. The family home was a true Victorian styled home which probably led a young Arne Jacobsen to paint the walls in his room white as a contrast to the lavishly decorated interior. 10 11 12 13 A natural talent for painting At the age of 11 Arne Jacobsen was sent away to a boarding school. -

Denmark's Central Bank Nationalbanken

DANMARKS NATIONALBANK THE DANMARKS NATIONALBANK BUILDING 2 THE DANMARKS NATIONALBANK BUILDING DANMARKS NATIONALBANK Contents 7 Preface 8 An integral part of the urban landscape 10 The facades 16 The lobby 22 The banking hall 24 The conference and common rooms 28 The modular offices 32 The banknote printing hall 34 The canteen 36 The courtyards 40 The surrounding landscaping 42 The architectural competition 43 The building process 44 The architect Arne Jacobsen One of the two courtyards, called Arne’s Garden. The space supplies daylight to the surrounding offices and corridors. Preface Danmarks Nationalbank is Denmark’s central bank. Its objective is to ensure a robust economy in Denmark, and Danmarks Nationalbank holds a range of responsibilities of vital socioeconomic importance. The Danmarks Nationalbank building is centrally located in Copen hagen and is a distinctive presence in the urban landscape. The build ing, which was built in the period 1965–78, was designed by interna tionally renowned Danish architect Arne Jacobsen. It is considered to be one of his principal works. In 2009, it became the youngest building in Denmark to be listed as a historical site. When the building was listed, the Danish Agency for Culture highlighted five elements that make it historically significant: 1. The building’s architectural appearance in the urban landscape 2. The building’s layout and spatial qualities 3. The exquisite use of materials 4. The keen attention to detail 5. The surrounding gardens This publication presents the Danmarks Nationalbank building, its architecture, interiors and the surrounding gardens. For the most part, the interiors are shown as they appear today. -

Arne Jacobsen the Egg Chair ™ in Genuine Greenlandic Sealskin

PRESS Adding value to the world’s most difficult supply chains A Danish design icon in Greenland Arne Jacobsen the Egg Chair ™ in genuine Greenlandic sealskin På vej mod nye mål Exclusive limited edition by Numbered exclusive edition of Danish design classic: A limited edition of the original Fritz Hansen The Egg ™ is being produced for Arctic Living in Nuuk. Each chair is covered with unique sealskin - and no two chairs are alike. Experience the chair in Arctic Living in Nuuk. The Egg ™ in Greenlandic sealskin. You know the chair and the architect who designed it. As a tribute to both, Arctic Import - who owns the lifestyle store Arctic Living in Nuuk – is getting a limited and numbered amount of the Egg ™ produced. Each chair is covered with its own unique genuine Greenlandic sealskin. On the interior Hos Arctic Import har vi travlt. Og det har vi haft igennem seating surfaces, the customer can either choose Classic- alle vores 25 år i Grønland. Det er vi glade og stolte over. leather or Elegance-leather. Masser af erfaringer og indgående kendskab til det grøn- landske erhvervsliv har gjort os til en sikker og kompetent samarbejdspartner. Vi er vokset og har udviklet os i tæt For more information - contact sales manager Martin Pedersen, The Egg ™ was designed in parløb med vores kunder – og med respekt for det, der gør mobile +45 40216612, e-mail [email protected] or shop 1958 for SAS Royal Hotel in Grønland til noget helt specielt. Copenhagen. The Egg ™ is a joy to manager Karina Holmstrøm Petersen, tel. -

Scandi Navian Design Catalog

SCANDI NAVIAN DESIGN CATALOG modernism101 rare design books Years ago—back when I was graphic designing—I did some print advertising work for my friend Daniel Kagay and his business White Wind Woodworking. During our collaboration I was struck by Kagay’s insistent referral to himself as a Cabinet Maker. Hunched over my light table reviewing 35mm slides of his wonderful furniture designs I thought Cabinet Maker the height of quaint modesty and humility. But like I said, that was a long time ago. Looking over the material gathered under the Scandinavian Design um- brella for this catalog I now understand the error of my youthful judgment. The annual exhibitions by The Cabinet-Makers Guild Copenhagen— featured prominently in early issues of Mobilia—helped me understand that Cabinet-Makers don’t necessarily exclude themselves from the high- est echelons of Furniture Design. In fact their fealty to craftsmanship and self-promotion are constants in the history of Scandinavian Design. The four Scandinavian countries, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland all share an attitude towards their Design cultures that are rightly viewed as the absolute apex of crafted excellence and institutional advocacy. From the first issue of Nyt Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri published by The Danish Society of Arts and Crafts in 1928 to MESTERVÆRKER: 100 ÅRS DANSK MØBELSNEDKERI [Danish Art Of Cabinetmaking] from the Danske Kunstindustrimuseum in 2000, Danish Designers and Craftsmen have benefited from an extraordinary collaboration between individuals, manufacturers, institutions, and governments. The countries that host organizations such as The Association of Danish Furniture Manufacturers, The Association of Furniture Dealers in Denmark, The Association of Interior Architects, The Association of Swedish Furni- ture Manufacturers, The Federation of Danish Textile Industries, Svenska Slojdforeningen, The Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo put the rest of the globe on notice that Design is an important cultural force deserv- ing the height of respect. -

Kystvejen Find Vej I Danmark - På Rulleskøjter “Find Vej På Kystvejen” Er Et Spændende Tilbud Til Rul- - Er En Oplevelse, Hvor Man Ved Brug Af Leskøjteløbere

Velkommen til rulleskøjteorientering på Kystvejen Find vej i Danmark - på rulleskøjter “Find vej på Kystvejen” er et spændende tilbud til rul- - er en oplevelse, hvor man ved brug af leskøjteløbere. Det går ud på at finde vej langs kortet orientere alene, som familie eller kystvejen i Charlottenlund. sammen med andre. Husk at følge fær- Følg ruten og find de steder på kortet der er markeret selsreglerne. Du kan også orientere dig til med et tal. fods, løbe eller på løbehjul. Find posterne ved hjælp af billederne. Det gælder om at finde alle posterne, som har et bogstav tilknyttet. Orienteringsløb for alle og hele familien KYSTVEJEN Når man har fundet alle posterne og dermed også alle langs Øresund. Find posterne på ruten efter FRA CHARLOTTENLUND FORT bogstaverne, skal man sætte bogstaverne i den rigtige TIL KLAMPENBORG rækkefølge, så de danner det korekte ord. vejledningen. ROL er motion og oplevelser, der både giver spænding og træning. Der kan Du kan finde en kort fortælling til posterne bagpå konkurreres i at finde posterne og fortælles kortet. Det handler om at opdage de spændende his- historier om de lokaliteter, der ses. torier, der gemmer sig på ruten. Er der temaer du bliver interesseret i kan du fortsætte jagten på nye historier, Ruten kan både løbes på rulleskøjter og i når du kommer hjem. løbesko. De yngste kan tage turen af flere Rulleskøjte Orienterings Løb handler om at få sjov omgange og det er muligt at indlægge pau- motion, hvor du kan kombinere aktiviteten på hjul, rul- ser undervejs. Hele ruten er 10 Km. frem og leskøjter, skateboard eller løbehjul med oplevelser og tilbage. -

Arne Jacobsen DESCRIPTION

AJ52 | SOCIETY TABLE – Design: Arne Jacobsen DESCRIPTION The AJ52 Society Table by Arne Jacobsen is a distinctive piece featuring a desk, lamp, table shelf and drawers in one seemingly floating piece. It brilliantly showcases Jacobsen's ability to make the complex appear simple. The desk is made of solid wood, veneer and steel and the tabletop is covered with fine-structured leather that opens at the corners to expose the legs. The wooden shelf has two compartments with glass sides and the integrated lamp is made in brushed stainless-steel. Attached with four metal tubes, the drawer unit appears suspended beneath the table, adding to the overall impression of lightness. The elements create a sophisticated, modern and elegant work desk. The AJ52 Society Table is available in two sizes and the six-drawer unit can be mounted on either side of the desk. The shelf and integrated lamp are optional. THE DESIGNER His precise yet expressive aesthetic continues to serve as a source of inspiration for contemporary designers, and his furniture designs, most created in connection with specific architectural projects, continue to excite both in Denmark and abroad. Above all else, Jacobsen viewed himself as an architect. Today, the National Bank of Denmark, the Bellavista housing estate north of Copenhagen, the Bellevue Theater north of Copenhagen and the Aarhus City Hall attest to his mastery of this realm. His extensive portfolio of functionalist buildings includes everything from small holiday homes to large projects, with everything, down to the cutlery and the door handles, bearing his personal touch. One of the best-known examples of Jacobsen's work is the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen (now the Radisson Blu Royal Hotel), where he was responsible not only for the architecture, but also for all interior design elements. -

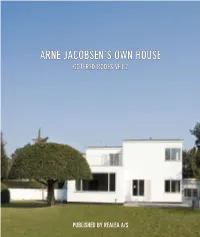

Download the Publication Arne Jacobsen's Own House

BIBLIOGRAPHY Henrik Iversen, ‘Den tykke og os’, Arkitekten 5 (2002), pp. 2-5. ARNE JACOBSEN Arne Jacobsen, ‘Søholm, rækkehusbebyggelse’, Arkitektens månedshæfte 12 (1951), pp. 181-90. Arne Jacobsen’s Architect and Designer The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, Gentofte. Atlas over bygninger og bymiljøer. Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen (1956-1965). Copenhagen: The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, 2004. He was born on 11 February 1902 in Copenhagen. Ernst Mentze, ‘Hundredtusinder har set og talt om dette hus’, Berlingske Tidende 10 October 1951. His father, Johan Jacobsen was a wholesaler. Félix Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Arne Jacobsen. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1989. Own House His mother, Pouline Jacobsen worked in a bank. Carsten Thau og Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag, 1998. He graduated from Copenhagen Technical School in 1924. www.arne-jacobsen.com Attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture in www.realdania.dk Copenhagen (1924-1927) Original drawings from the Danish National Art Library, The Collection of Architectural Drawings Strandvejen 413 He worked at the Copenhagen City Architect’s office (1927-1929) From 1930 until his death in 1971, he ran his own practice. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Peter Thule Kristensen, DPhil, PhD is an architect and a professor at the Institute of Architecture and JACK OF ALL TRADES Design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK), where he is in charge of the post-graduate Spatial Design programme. He is also a core A total one of a kind, Arne Jacobsen was world famous. -

Ekskurzija Danska, Nemčija Seminar Zorec 09

ekskurzija Danska, Nemčija seminar Zorec 09 "My laboratory is the beach, the forest, the sea and seashore..". "The true innermost being of architecture can be compared with that of nature’s seed, and something of inevitability of nature’s prin- ciple of growth ought to be a fundamental concept in architecture." “On the road from the first idea - the first sketch - to the final build- ing, a host of possibilities arise for the architect and the team of engineers, contractors and artisans. Only when the foundation for the choice between the various solutions derives from the aware- ness that the building must provide the people who are to live in it with delight and inspiration do the correct solutions to the problems fall like ripe fruits.” Jørn Utzon 2 DANSKA Dansko kraljestvo (krajše le Danska) je najstarejša in najmanjša nor- dijska država, ki se nahaja v Skandinaviji v severni Evropi na polotoku vzhodno od Baltskega morja in jugozahodno od Severnega morja. Vključuje tudi številne otoke severno od Nemčije, na katero meji tudi po kopnem, in Poljske, poleg teh pa še ozemlja na Grenlandiji in Fer- skih otokih, ki so združena pod dansko krono, čeprav uživajo samou- pravo. Le četrtina teh otokov je naseljena. Danska je izrazito položna dežela. Najvišji vrh je Ejer Bavnehoj, z 173 metri nadmorske višine. Največja reka je Gudena. zanimivosti: - Danska je mati Lego kock. Njihova zgodba se je začela leta 1932 in v več kot 60. letih so prodali čez 320 bilijonov kock, kar pomeni povprečno 56 kock na vsakega prebivalca na svetu. Zabaviščni park Legoland se nahaja v mestu Billund, kjer so zgrajene različne fingure in modeli iz več kot 25 milijonov lego kock. -

11 the Garden of Arne Jacobsen's Own House in 'Søholm I'

RA 20 299 11 key elements related to natural conditions of each specific location, and thanks to gardens that balance the whole composition and justify the connection between inner and outer spaces of each The garden of Arne architectural design. In all of his five family houses, the garden and the land- jacobsen’s own house in scape turn out to be essential aspects due to different reasons: in his modern, functionalist house in Ordrup-Charlottenlund (1928-29), ‘Søholm I’: an open Space for the garden is a little more than a lawn with a pair of trees because the real garden is placed in the house, creating a dense, vegetal at- Landscape design Testing mosphere in the living-room; in the vernacular house in Gudmindrup Lyng (1936-38) near the Sejrø bay, the garden becomes a just quiet Rodrigo Almonacid haven outdoors sheltered by a sand dune and a nearby pine wood, since growing plants is not feasible only in summer holidays; in the modest row-houses at Sløjfen street in Gentofte (1943), the garden The Danish architect Arne Jacobsen (1902-71) made the most of becomes a domestic patch for growing some vegetables and fruits every project for his own family houses by designing avant-garde, just after the Second World War; at the innovating housing “Søholm highly experimental solutions. For his single-family house in the I” in Klampenborg (1946-50) on the shores of the Øresund sea, the Søholm row-houses (Klampenborg, 1946-50) the experimentation garden of his office-house turns into a living courtyard for continu- with the architectural project not only entailed designing domes- ous enjoyment in which he can develop his abilities as a gardener, tic architecture but also the private garden. -

Arkitektur Og Arkitekter

ARKITEKTUR OG ARKITEKTER Landsteder Landstedet - som en særlig bygningskategori beregnet for velstående familiers sommerophold - optræder først sent i Danmark. Frem til enevældens indførelse boede landets topfolk, adelsmændene, på deres herregårde rundt i landet. For at kunne varetage embederne i statens tjeneste havde de som regel en gård eller et palæ stående til rådighed i hovedstaden. Med enevælden i 1660 bortfaldt adelens selvfølge- lige ret til statens embeder. Kongen valgte herefter de embedsmænd, han ønskede blandt duelige borgere. De havde deres helårsbolig i byen og kunne have behov for et sommerfristed, fjernt fra byens tummel og stank. De borgerlige landsteder knyttede sig gerne til de kongelige opholdssteder og tilpas nær hovedstaden. Et af de allerførste landsteder i Gentofte var Chris- Den nordvendte hovedindgang til Bernstorff Slot er Refendfugningen på Bernstorff Slots er elegant trukket tiansholm, opført for historikeren Vitus Bering i omfattet af en portal med profilerede gerichter og en med hele vejen rundt om det store fremspringende udkraget gesims. Indgangen flankeres af to dekora- midterparti til havesiden 1670. Blot ti år efter enevældens indførelse. Det tive fyldningspartier. oprindelige Christiansholm blev i 1746 erstattet af det nuværende, en fornem rokokobygning, med ni gange syv fag og midtrisalitter på alle fire facader. Tilsvarende med nabolandstedet Sølyst, som op- rindeligt var fra 1724, men blev nyopført i 1766 i en enkel klassisk stil - ikke ulig mangen en mindre herregård. Hovedhuset er syv fag langt og centreret omkring en trefags midtrisalit. To pavilloner flan- kerer hovedhuset. Det samlede anlæg, som er holdt i beskedne proportioner, fremstår elegant i sin hvid- malede, vandrette træbeklædning. Se også side 24. -

Arne Jacobsen I Gentofte

Arne Jacobsen i Gentofte Undervisningsmateriale om arkitekten Arne Jacobsens design og arkitektur 4. – 7. klassetrin Arne Jacobsen i Gentofte Den kommune du bor i, er det sted i verden hvor der findes flest bygninger af den verdensbe- rømte arkitekt Arne Jacobsen. Arne Jacobsen bliver født i 1902 i København. Han er rigtig god til at tegne og male, og vil ger- ne være kunstner. Hans far mener, at han skal være arkitekt. Derfor starter Arne Jacobsen på Kunstakademiets Arkitektskole i København i 1924. Han er en dygtig arkitekt og bliver kendt over hele verden. Arne Jacobsen vil gerne bestemme, hvordan hans bygninger indrettes. Derfor bliver Arne Jacobsen. Foto udlånt af KAB han også designer, og tegner stole, borde, lam- per og meget andet til sine huse. Det er særligt For at forstå Arne Jacobsens bygninger er det de stole han designer, der gør ham verdensbe- ikke nok, at læse om dem. Du skal også ud og rømt. opleve dem i virkeligheden. Det har du god Arne Jacobsen dør i 1971. I 2002 ville han være mulighed for, for mange af bygningerne ligger fyldt 100 år. lige i nærheden af, hvor du bor. Design Arkitektur En designer er en person, der giver form til ting. Arkitektur er de rum og bygninger vi bevæger De ting du bruger i din dagligdag har alle en os rundt i til daglig. funktion: En kniv skal være skarp, så du kan En arkitekt er en person, der giver form til disse skære med den. Din skoletaske skal have plads rum og bygninger. til bøger, penalhus og madkasse, og den skal Alle bygninger har et formål: Dit hus skal give være god at bære på ryggen. -

Arne Jacobsen's Own House

LITERATURE JACOBSEN, ARNE Carsten Thau and Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, Copenhagen 1998. Buildings are an aspect of our (1902-1971) Architect and Designer Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Nordische Baukunst, Berlin 1940. cultural heritage: a tangible relic that Arne Jacobsen was born on February 11, 1902 in Copenhagen. Peter Thule Kristensen, Det sentimentalt moderne: Romantiske ledemotiver i det 20. our ancestors have handed down to us, His father, Johan Jacobsen, was a wholesaler. århundredes bygningskunst, Copenhagen 2006. His mother, Pouline Jacobsen, was specially trained to work in a bank. which we are obligated to safeguard. Arkitekten, monthly magazine 4-5, 1932. ARNE JACOBSEN’S OWN HOUSE Lisbet Balslev Jørgensen, Danmarks arkitektur, Enfamiliehuset, Copenhagen 1985. 1924 - Graduated from the Technical School in Copenhagen. Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in, Almanach de l’Architecture moderne, Paris 1926. Realea A/S is a real estate fi rm that GOTFRED RODES VEJ 2 1924-1927 - Attended the Royal Danish Academy of Art’s School Félix Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Arne Jacobsen, Barcelona 1989. is dedicated to development and of Architecture in Copenhagen. www.arne-jacobsen.com preservation. The fi rm’s express 1927-1929 - Staff employee working at the office of the municipal architect in Copenhagen. www.realea.dk purpose is to build up a collection 1956-1965 - Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Art in Copenhagen Original drawings from Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Collection of architectural drawings. 1930-1971 - From 1930 up until his death in 1971, operated his own drawing office. of unique properties and to impart knowledge about them and also to preserve important examples of A JACK-OF-ALL-TRADES ABOUT THE AUTHOR building styles and architecture from Arne Jacobsen was an individualist, marching to the rhythm of his own drummer.