1 Losada JM, Herrero M, Hormaza JI and Friedman WE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi Hanna M. Miller University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Hanna M., "Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi" (2016). Honors Theses. 389. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/389 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi by Hanna Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences May 2016 ii Approved by _________________________________ Mac H. Alford, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract The North American Coastal Plain contains some of the highest plant diversity in the temperate world. However, most of the region has remained unstudied, resulting in a lack of knowledge about the unique plant communities present there. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Approved Plants For

Perennials, Ground Covers, Annuals & Bulbs Scientific name Common name Achillea millefolium Common Yarrow Alchemilla mollis Lady's Mantle Aster novae-angliae New England Aster Astilbe spp. Astilbe Carex glauca Blue Sedge Carex grayi Morningstar Sedge Carex stricta Tussock Sedge Ceratostigma plumbaginoides Leadwort/Plumbago Chelone glabra White Turtlehead Chrysanthemum spp. Chrysanthemum Convallaria majalis Lily-of-the-Valley Coreopsis lanceolata Lanceleaf Tickseed Coreopsis rosea Rosy Coreopsis Coreopsis tinctoria Golden Tickseed Coreopsis verticillata Threadleaf Coreopsis Dryopteris erythrosora Autumn Fern Dryopteris marginalis Leatherleaf Wood Fern Echinacea purpurea 'Magnus' Magnus Coneflower Epigaea repens Trailing Arbutus Eupatorium coelestinum Hardy Ageratum Eupatorium hyssopifolium Hyssopleaf Thoroughwort Eupatorium maculatum Joe-Pye Weed Eupatorium perfoliatum Boneset Eupatorium purpureum Sweet Joe-Pye Weed Geranium maculatum Wild Geranium Hedera helix English Ivy Hemerocallis spp. Daylily Hibiscus moscheutos Rose Mallow Hosta spp. Plantain Lily Hydrangea quercifolia Oakleaf Hydrangea Iris sibirica Siberian Iris Iris versicolor Blue Flag Iris Lantana camara Yellow Sage Liatris spicata Gay-feather Liriope muscari Blue Lily-turf Liriope variegata Variegated Liriope Lobelia cardinalis Cardinal Flower Lobelia siphilitica Blue Cardinal Flower Lonicera sempervirens Coral Honeysuckle Narcissus spp. Daffodil Nepeta x faassenii Catmint Onoclea sensibilis Sensitive Fern Osmunda cinnamomea Cinnamon Fern Pelargonium x domesticum Martha Washington -

Magnolias for the Delaware Valley by Andrew Bunting

Feature Article Magnolias for the Delaware Valley By Andrew Bunting he magnolia is perhaps the most northern South American including ‘Brozzonii’ Thighly regarded of all the spring with 27 species alone in (white with a rose- flowering trees for the Delaware Val- Colombia! There are no purple base); ‘Norbertii’ ley. Walking around Swarthmore on native species in Europe (soft pink flowers); an early April day, you will hardly or Africa, but extensive and ‘Alexandrina’ pass a house that doesn’t have at least speciation in Asia. Many (striking white inner one magnolia in the yard. Many of the deciduous species are tepals, contrasting old homes have extraordinary speci- found in China, Japan, with dark purple outer mens of saucer magnolia (Magnolia and South Korea, as tepals). For the small × soulangeana), some well over 80 well as many evergreen garden, ‘Liliputian’ is a years old. Walk on down Chester Road species in southeastern diminutive selection. toward Swarthmore College and you Asia, especially Vietnam, Yulan magnolia (M. will be greeted by outstanding speci- Thailand, and Myanmar, Magnolia x soulangeana denudata) is one of the mens of saucer magnolia, Yulan mag- with distribution 'Alexandrina' parents of this exquisite nolia (Magnolia denudata), Loebner continuing as far south as Papua, New hybrid. This species can bloom magnolia (Magnolia × loebneri), and Guinea. slightly before the saucer magnolias the star magnolia (Magnolia stellata). The early spring flowering in late March and runs the risk of The Scott Arboretum of Swarthmore magnolias are the ones perhaps most getting frosted on chilly evenings; College holds a national collection of coveted for our region. -

Magnolia (Magnolia Grandiflora and Magnolia Virginiana)

.DOCSA 13.31:M 27/970 s t MAGNOLIA Eight species of magnolia are native to the United States, the most important being southern magnolia and sweetbay. Magnolia wood resembles yellow- poplar in appearance and properties. lt is light in color; the sapwood is white, the heartwood light to dark brown. Of moderate density, high in shock resistance, and easy to work, it is used chiefly for furniture, kitchen cabinets, and interior woodwork requiring paint linishes. Some is made into veneer or use in boxes and crates. U.S. Department of Agriculture jrest Service 0 TÁmerican WoodFS,-245 Revised July 1970 . I MAGNOLIA (Magnolia grand flora and Magnolia virginiana) Louis C. Maisenhelder DISTRIBUTION extends farther north. The species grows along the Atlantic Coastal Plain from Long Island south through The range of southern magnolia (Magnolia grandi- to southern tiora) includes a narrow strip, approximately 100 miles New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania into southern wide, taking in the coast of South Carolina and the Florida, west to eastern Texas, and north Arkansas and southwest Tennessee; also locally in extreme southeast corner of North Carolina ; roughly eastern Massachusetts. Its greatest abundance is in southern Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi ; the northern half of Florida; and parts of Louisiana, eastern Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Caro- lina. In bottomlands, it occurs mainly east of the Mis- southern Arkansas, and east Texas (fig. 1) . Its greatest abundance (and, therefore, commercial importance) is sissippi River in muck swamps of the Coastal Plains. in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas, where it occurs In uplands, it occurs only in moist streamheads of the on relatively moist bottomland sites. -

Magnolia Obovata

ISSUE 80 INAGNOLN INagnolla obovata Eric Hsu, Putnam Fellow, Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University Photographs by Philippe de 8 poelberch I first encountered Magnolia obovata in Bower at Sir Harold Hillier Gardens and Arboretum, Hampshire, England, where the tightly pursed, waxy, globular buds teased, but rewarded my patience. As each bud unfurled successively, it emitted an intoxicating ambrosial bouquet of melons, bananas, and grapes. Although the leaves were nowhere as luxuriously lustrous as M. grandrflora, they formed an el- egant wreath for the creamy white flower. I gingerly plucked one flower for doser observation, and placed one in my room. When I re- tumed from work later in the afternoon, the mom was overpowering- ly redolent of the magnolia's scent. The same olfactory pleasure was later experienced vicariously through the large Magnolia x wiesneri in the private garden of Nicholas Nickou in southern Connecticut. Several years earlier, I had traveled to Hokkaido Japan, after my high school graduation. Although Hokkaido experiences more severe win- ters than those in the southern parts of Japan, the forests there yield a remarkable diversity of fora, some of which are popular ornamen- tals. When one drives through the region, the silvery to blue-green leaf undersides of Magnolia obovata, shimmering in the breeze, seem to flag the eyes. In "Forest Flora of Japan" (sggII), Charles Sargent commended this species, which he encountered growing tluough the mountainous forests of Hokkaido. He called it "one of the largest and most beautiful of the deciduous-leaved species in size and [the seed conesj are sometimes eight inches long, and brilliant scarlet in color, stand out on branches, it is the most striking feature of the forests. -

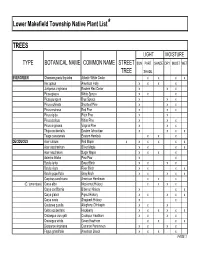

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Lithospermum Canescens Hoary Puccoon

Sweet Bay Magnolia Magnolia virginiana ………………………….………………………………………………………………………………….. Description Sweet bay magnolia is a semi-evergreen tree that is often multistemmed and may grow to 65 feet (20 meters) tall, but in Pennsylvania is usually much smaller. The leaves are alternately arranged, thickish in texture, untoothed on the margin, noticeably whitish on the lower surface, elliptic in shape, and from 3 to 5 inches (7.5-13 cm) long. The fragrant white flowers, appearing in May and June, are relatively large and showy, approximately 2 to 3 inches (5- 7.5 cm) wide. The fruit is a 2 inch (5 cm) cone-like structure containing seeds that have a red or orange outer covering. Distribution & Habitat Sweet bay magnolia has a coastal range from southern New England west and south into Texas and Florida. In Pennsylvania, it represents Photo source: R. Harrison Wiegand a southerly species and has been documented in several southeastern counties. It occurs in wetlands, particularly swamps and seepy woodlands. North American State/Province Conservation Status Current State Status Map by NatureServe 2014 The PA Biological Survey (PABS) considers sweet bay magnolia to be a species of special concern, based on the few occurrences that have been recently confirmed, its limited state range, State/Province and its wetland habitat. It has a PA legal rarity Status Ranks status and a PABS suggested rarity status of Threatened. About 20 populations, most with few individuals, have been documented in the state. Conservation Considerations: The viability of populations of sweet bay magnolia and its habitat type will be enhanced by creating buffers around wetlands, controlling invasive species, and protecting the hydrology of the wetland and its surroundings. -

The Progressive and Ancestral Traits of the Secondary Xylem Within Magnolia Clad – the Early Diverging Lineage of Flowering Plants

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Acta Soc Bot Pol 84(1):87–96 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.2014.028 Received: 2014-07-31 Accepted: 2014-12-01 Published electronically: 2015-01-07 The progressive and ancestral traits of the secondary xylem within Magnolia clad – the early diverging lineage of flowering plants Magdalena Marta Wróblewska* Department of Developmental Plant Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, University of Wrocław, Kanonia 6/8, 50-328 Wrocław, Poland Abstract The qualitative and quantitative studies, presented in this article, on wood anatomy of various species belonging to ancient Magnolia genus reveal new aspects of phylogenetic relationships between the species and show evolutionary trends, known to increase fitness of conductive tissues in angiosperms. They also provide new examples of phenotypic plasticity in plants. The type of perforation plate in vessel members is one of the most relevant features for taxonomic studies. InMagnolia , until now, two types of perforation plates have been reported: the conservative, scalariform and the specialized, simple one. In this paper, are presented some findings, new to magnolia wood science, like exclusively simple perforation plates in some species or mixed perforation plates – simple and scalariform in one vessel member. Intravascular pitting is another taxonomically important trait of vascular tissue. Interesting transient states between different patterns of pitting in one cell only have been found. This proves great flexibility of mechanisms, which elaborate cell wall structure in maturing trache- ary element. The comparison of this data with phylogenetic trees, based on the fossil records and plastid gene expression, clearly shows that there is a link between the type of perforation plate and the degree of evolutionary specialization within Magnolia genus. -

Parakmeria Omeiensis (Magnoliaceae), a Critically Endangered Plant Species Endemic to South-West China

Integrated conservation for Parakmeria omeiensis (Magnoliaceae), a Critically Endangered plant species endemic to south-west China D AOPING Y U ,XIANGYING W EN,CEHONG L I ,TIEYI X IONG,QIXIN P ENG X IAOJIE L I ,KONGPING X IE,HONG L IU and H AI R EN Abstract Parakmeria omeiensis is a Critically Endangered tree attractive and large, and their seed arils are orange, making species in the family Magnoliaceae, endemic to south-west the tree an attractive ornamental plant. However, the species China. The tree is functionally dioecious, but little is known has a restricted range. It has been considered a Grade-I about the species’ status in the wild. We investigated the Key-Protected Wild Plant Species in China since and range, population size, age structure, habitat characteristics has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the and threats to P. omeiensis. We located a total of individuals IUCN Red List since (China Expert Workshop, ), in two populations on the steep slopes of Mount Emei, Sichuan the Chinese Higher Plants Red List since (Yin, ), and province, growing under the canopy of evergreen broadleaved the Red List of Magnoliaceae since (Malin et al., ). forest in well-drained gravel soil. A male-biased sex ratio, lack The tree has also been identified as a plant species with an of effective pollinating insects, and habitat destruction result extremely small population (Ren et al., ; State Forestry in low seed set and poor seedling survival in the wild. We Administration of China, ). have adopted an integrated conservation approach, including Parakmeria includes five species (P. -

SMALL DEPRESSION SHRUB BORDER Concept

SMALL DEPRESSION SHRUB BORDER Concept: Small Depression Shrub Border communities are narrow shrub thickets that occur as an outer zone on the rims of Small Depression Pond, Small Depression Drawdown Meadow, and Vernal Pool communities. These communities are narrow enough to be strongly subject to edge effects from both sides. They contain a mix of pocosin species, such as Cyrilla racemiflora, Lyonia lucida, and Smilax laurifolia, along with some characteristic pond species such as Ilex myrtifolia, Ilex cassine, Litsea aestivalis, and Cephalanthus occidentalis. Trees may be sparse or dense but have little effect on the shrubs because of open edges. They may include Pinus serotina, but more often will be Nyssa biflora, Acer rubrum, Magnolia virginiana, and Persea palustris. Herbaceous species of the adjacent open wetland and the adjacent upland are usually present. Distinguishing Features: Small Depression Shrub Border is distinguished from all other communities by the combination of shrub dominance and occurrence in a narrow zone on the edge of other, more open depressional wetlands. Small Depression Pocosins may contain some of the same species but will fill most or all of the basins they occur in and will not contain an appreciable amount of Ilex myrtifolia, Ilex cassine, Litsea aestivalis, or Cephalanthus occidentalis. Natural Lake Communities may share some species, but generally have a limited shrub layer. They occur on larger bodies of water where wave action is important. Synonyms: Cyrilla racemiflora - Lyonia lucida Shrubland (CEGL003844). Small Depression Pond (3rd Approximation). Ecological Systems: Southern Atlantic Coastal Plain Depression Pondshore (CES203.262). Sites: Small Depression Shrub Border communities occur primarily in limesinks but can occur in small Carolina bays and in relict dune swales.