Packet Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live Oak Banking Company 2605 Iron Gate Dr, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Jpmorgan Chase Bank, National 1111 Polaris Pkwy 2013 7(A) U.S

APPVFY MAJPGM L2Name L2Street 2013 7(A) Wells Fargo Bank, National Ass 101 N Philips Ave 2013 7(A) Live Oak Banking Company 2605 Iron Gate Dr, Ste 100 2013 7(A) JPMorgan Chase Bank, National 1111 Polaris Pkwy 2013 7(A) U.S. Bank National Association 425 Walnut St 2013 7(A) The Huntington National Bank 17 S High St 2013 7(A) Ridgestone Bank 13925 W North Ave 2013 7(A) Seacoast Commerce Bank 11939 Ranho Bernardo Rd 2013 7(A) Wilshire State Bank 3200 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 1400 2013 7(A) Compass Bank 15 S 20th St 2013 7(A) Hanmi Bank 3660 Wilshire Blvd PH-A 2013 7(A) Celtic Bank Corporation 268 S State St, Ste 300 2013 7(A) KeyBank National Association 127 Public Sq 2013 7(A) Noah Bank 7301 Old York Rd 2013 7(A) BBCN Bank 3731 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 1000 2013 7(A) TD Bank, National Association 2035 Limestone Rd 2013 7(A) Manufacturers and Traders Trus One M & T Plaza, 15th Fl 2013 7(A) Newtek Small Business Finance, 212 W. 35th Street 2013 7(A) SunTrust Bank 25 Park Place NE 2013 7(A) Hana Small Business Lending, I 1000 Wilshire Blvd 2013 7(A) First Bank Financial Centre 155 W Wisconsin Ave 2013 7(A) NewBank 146-01 Northern Blvd 2013 7(A) Open Bank 1000 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Bank of the West 180 Montgomery St 2013 7(A) CornerstoneBank 2060 Mt Paran Rd NW, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Synovus Bank 1148 Broadway 2013 7(A) Comerica Bank 1717 Main St 2013 7(A) Borrego Springs Bank, N.A. -

3A Expanded Small Business Lending

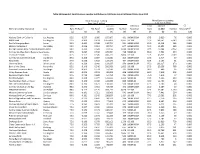

Table 3A Expanded. Small Business Lending Institutions in California Using Call Report Data, June 2012 Small Business Lending Micro Business Lending (less than $ million) (less than $ 100k) Total Amount Institution Total Amount CC Name of Lending Institution City Rank TA Ratio1 TBL Ratio1 (1,000) Number Asset Size Rank (1,000) Number Amount/TA1 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) National Bank of California Los Angeles 95.0 0.537 1.000 187,467 431 100M-500M 67.5 3,020 76 0.000 BBCN Bank Los Angeles 92.5 0.309 0.424 1,557,424 9,537 1B-10B 97.5 168,741 6,149 0.000 Pacific Enterprise Bank Irvine 92.5 0.405 0.549 110,755 591 100M-500M 95.0 11,314 249 0.000 Mission Valley Bank Sun Valley 90.0 0.356 0.564 87,754 647 100M-500M 95.0 12,892 365 0.000 Borrego Springs Bank, National AssociLa Mesa 90.0 0.435 0.628 65,123 3,020 100M-500M 97.5 10,544 2,562 0.000 Community West Bank, National Asso Goleta 87.5 0.227 0.542 129,084 718 500M-1B 85.0 7,591 234 0.000 Tri Counties Bank Chico 87.5 0.173 0.545 436,723 3,804 1B-10B 97.5 43,955 2,289 0.000 Community Commerce Bank Claremont 87.5 0.358 0.687 103,416 365 100M-500M 67.5 2,717 57 0.000 Plaza Bank Irvine 87.5 0.328 0.502 127,075 484 100M-500M 52.5 2,193 61 0.000 Universal Bank West Covina 85.0 0.329 1.000 133,617 170 100M-500M 95.0 133,617 170 0.000 Bank of the Sierra Porterville 85.0 0.148 0.546 206,583 1,602 1B-10B 97.5 20,356 768 0.000 Seacoast Commerce Bank San Diego 82.5 0.363 0.574 57,144 315 100M-500M 30.0 409 16 0.000 Valley Business Bank Visalia 82.5 0.259 0.531 89,428 408 100M-500M 90.0 -

Preservation and Promotion of Minority Depository Institutions Report to Congress for 2015

Preservation and Promotion of Minority Depository Institutions Report to Congress for 2015 Preservation and Promotion of Minority Depository Institutions The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Report to Congress for 2015 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Summary Profile of Minority Depository Institutions ...................................................... 1 Structure ................................................................................................................. 1 Performance ........................................................................................................... 2 FDIC National Minority Depository Institutions Program ............................................... 2 2015 Initiatives Supporting Minority Depository Institutions ......................................... 3 Technical Assistance ..................................................................................................... 5 Outreach, Training and Educational Programs ............................................................. 6 Failing Institutions .......................................................................................................... 6 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 6 Attachments .................................................................................................................. 7 FDIC’s -

INSURED U.S.-CHARTERED COMMERCIAL BANKS THAT HAVE CONSOLIDATED ASSETS of $100 MILLION OR MORE RANKED by CONSOLIDATED ASSETS As of March 31, 2001

INSURED U.S.-CHARTERED COMMERCIAL BANKS THAT HAVE CONSOLIDATED ASSETS OF $100 MILLION OR MORE RANKED BY CONSOLIDATED ASSETS as of March 31, 2001 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Consol. Domestic Dom Cuml Number of I % Fgn Natl Bank Name Assets Assets As % As % Branches B Fgn Own Rank Dist Bank ID Holding Company Name Bank Location Chtr (Mil $) (Mil $) Cons Cons Dom Fgn F Own Typ ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 5 480228 BANK OF AMER NA CHARLOTTE NC NAT 553,509 486,720 88 9 4,715 38 Y 0 0 BANK OF AMER CORP 2 2 852218 CHASE MANHATTAN BK NEW YORK NY SMB 400,623 260,395 65 16 732 86 Y 0 0 J P MORGAN CHASE & CO 3 2 476810 CITIBANK NA NEW YORK NY NAT 395,869 142,655 36 23 287 413 Y 0 0 CITIGROUP 4 5 484422 FIRST UNION NB CHARLOTTE NC NAT 232,608 222,338 96 27 2,667 5 Y 0 0 FIRST UNION CORP 5 2 161415 MORGAN GUARANTY TC OF NY NEW YORK NY SMB 214,462 83,175 39 30 3 22 Y 0 0 J P MORGAN CHASE & CO 6 1 76201 FLEET NA BK PROVIDENCE RI NAT 200,887 174,186 87 34 1,809 198 Y 0 0 FLEETBOSTON FNCL CORP 7 7 173333 BANK ONE NA CHICAGO IL NAT 141,439 118,852 84 36 669 10 Y 0 0 BANK ONE CORP 8 12 451965 WELLS FARGO BK NA SAN FRANCISCO CA NAT 124,137 123,726 100 38 1,333 0 Y 0 0 WELLS FARGO & CO 9 6 675332 SUNTRUST BK ATLANTA GA SMB 100,443 100,443 100 40 1,243 1 Y 0 0 SUNTRUST BK 10 2 413208 HSBC BK USA BUFFALO NY SMB 81,826 71,484 87 41 466 28 Y 0 6 HSBC NORTH -

Domestic Bank Holding Companies Bank Charter Rssd Id New Fhc Direct Bank Holding Company Name City State Type Depository Institution Name

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO BANK HOLDING COMPANIES REGISTERED IN THE 12TH DISTRICT AND THEIR DEPOSIT-TAKING SUBSIDIARIES AS OF: 3/31/21 DOMESTIC BANK HOLDING COMPANIES BANK CHARTER RSSD ID NEW FHC DIRECT BANK HOLDING COMPANY NAME CITY STATE TYPE DEPOSITORY INSTITUTION NAME 0 1142587 FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK, LTD. TAIPEI 2332910 NMB FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK (U.S.A) ALHAMBRA CA 1242562 STATE BANK OF INDIA MUMBAI 779968 NMB STATE BANK OF INDIA (CALIFORNIA) LOS ANGELES CA AK 1989241 DENALI BANCORPORATION, INC. FAIRBANKS 571265 NMB DENALI STATE BANK FAIRBANKS AK 1416701 FHC FIRST BANCORP, INC. KETCHIKAN 451068 NMB FIRST BANK KETCHIKAN AK 3025385 NORTHRIM BANCORP, INC. ANCHORAGE 1718188 NMB NORTHRIM BANK ANCHORAGE AK AZ 3254363 CBOA FINANCIAL, INC. TUCSON 3131400 NMB COMMERCE BANK OF ARIZONA, INC. TUCSON AZ 3392443 COMMUNITY BANCSHARES, INC. KINGMAN 2963275 NMB MISSION BANK KINGMAN AZ 3382985 HORIZON BANCORP, INC. LAKE HAVASU CITY 3154780 NMB HORIZON COMMUNITY BANK LAKE HAVASU CITY AZ 3480050 WEST VALLEY BANCORP, INC. GOODYEAR 3480069 NAT WEST VALLEY NATIONAL BANK GOODYEAR AZ 2349815 WESTERN ALLIANCE BANCORPORATION PHOENIX 3138146 SMB WESTERN ALLIANCE BANK PHOENIX AZ 3559844 WESTERN ARIZONA BANCORP, INC. YUMA 3048487 NMB 1ST BANK YUMA YUMA AZ CA 1399765 1867 WESTERN FINANCIAL CORPORATION STOCKTON 479268 NMB BANK OF STOCKTON STOCKTON CA 5533567 1ST CAPITAL BANCORP SALINAS 3594797 NMB 1ST CAPITAL BANK SALINAS CA 4842721 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BANCORP CITY OF INDUSTRY 3216316 NMB AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BANK CITY OF INDUSTRY CA 2312837 AMERICAN RIVER BANKSHARES RANCHO CORDOVA 735768 NMB AMERICAN RIVER BANK SACRAMENTO CA 3680980 AVIDBANK HOLDINGS, INC. SAN JOSE 3214059 NMB AVIDBANK SAN JOSE CA 3033746 BAC FINANCIAL INC. -

Investing in the Future of Mission-Driven Banks a Guide to Facilitating New Partnerships PUBLISHED BY

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Investing in the Future of Mission-Driven Banks A Guide to Facilitating New Partnerships PUBLISHED BY: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation 550 17th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20429 877-ASK FDIC (877-275-3342) The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has taken steps to ensure that the information and data presented in this publication are accurate and current. However, the FDIC makes no express or implied warranty about such information or data, and hereby expressly disclaims all legal liability and responsibility to persons or entities that use or access this publication and its content, based on their reliance on any information or data included. The FDIC welcomes comments or suggestions about this publication or our Minority Depository Institutions (MDI) Program. Contact the MDI Program at [email protected]. When citing this publication, please use the following: Investing in the Future of Mission-Driven Banks, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Washington, D.C. (October 2020), https://www.fdic.gov/mdi. Investing in the Future of Mission-Driven Banks A Guide to Facilitating New Partnerships Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 2 Minority Depository Institutions ................................................................................. 2 Community -

Report: Domestic Bhcs and Fhbs

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO BANK HOLDING COMPANIES REGISTERED IN THE 12TH DISTRICT AND THEIR DEPOSIT-TAKING SUBSIDIARIES AS OF: 12/31/20 DOMESTIC BANK HOLDING COMPANIES BANK CHARTER RSSD ID NEW FHC DIRECT BANK HOLDING COMPANY NAME CITY STATE TYPE DEPOSITORY INSTITUTION NAME 0 1142587 FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK, LTD. TAIPEI 2332910NMB FIRST COMMERCIAL BANK (U.S.A) ALHAMBRA CA 1242562 STATE BANK OF INDIA MUMBAI 779968NMB STATE BANK OF INDIA (CALIFORNIA) LOS ANGELES CA AK 1989241 DENALI BANCORPORATION, INC. FAIRBANKS 571265NMB DENALI STATE BANK FAIRBANKS AK 1416701 FHC FIRST BANCORP, INC. KETCHIKAN 451068NMB FIRST BANK KETCHIKAN AK 3025385 NORTHRIM BANCORP, INC. ANCHORAGE 1718188NMB NORTHRIM BANK ANCHORAGE AK AZ 3254363 CBOA FINANCIAL, INC. TUCSON 3131400NMB COMMERCE BANK OF ARIZONA, INC. TUCSON AZ 3392443 COMMUNITY BANCSHARES, INC. KINGMAN 2963275NMB MISSION BANK KINGMAN AZ 3382985 HORIZON BANCORP, INC. LAKE HAVASU CITY 3154780NMB HORIZON COMMUNITY BANK LAKE HAVASU CITY AZ 3480050 WEST VALLEY BANCORP, INC. GOODYEAR 3480069NAT WEST VALLEY NATIONAL BANK GOODYEAR AZ 2349815 WESTERN ALLIANCE BANCORPORATION PHOENIX 3138146SMB WESTERN ALLIANCE BANK PHOENIX AZ 3559844 WESTERN ARIZONA BANCORP, INC. YUMA 3048487NMB 1ST BANK YUMA YUMA AZ CA 1399765 1867 WESTERN FINANCIAL CORPORATION STOCKTON 479268NMB BANK OF STOCKTON STOCKTON CA 5533567 1ST CAPITAL BANCORP SALINAS 3594797NMB ACQ 1ST CAPITAL BANK SALINAS CA 4842721 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BANCORP CITY OF INDUSTRY 3216316NMB AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BANK CITY OF INDUSTRY CA 2312837 AMERICAN RIVER BANKSHARES -

Election of Directors

August 23, 2021 ELECTION OF DIRECTORS To the Member Banks of the Twelfth District of the Federal Reserve: In accordance with the provisions of Section 4 of the Federal Reserve Act and the announcement dated July 14, 2021, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco is conducting an election of directors to succeed Mr. Greg Becker, a Class A director, elected by banks in Group One, and Mr. Arthur F. (Skip) Oppenheimer, a Class B director, elected by banks in Group Three, both of whose terms end on December 31, 2021, and Mr. Richard M. Sanborn, a Class A director, elected by banks in Group Two, whose term ended early on April 23, 2021, and whose unexpired term ends on December 31, 2022. In this election, each member financial institution in Group One may nominate one candidate for Class A director; Group Two may nominate one candidate for Class A Director; and each member financial institution in Group Three may nominate one candidate for Class B Director. Voting for these positions must be completed, via the online election system, by an officer who has been duly authorized to make nominations and cast votes on behalf of the member bank. If your bank has not previously designated an officer for this purpose, it may do so by a resolution of the bank’s board of directors or through a provision in the bank’s bylaws. If we have no record of such a designation, please send an email to [email protected]. Polls open today, Monday, August 23, 2021 at 9:00 a.m. -

San Francisco District Office 7(A) Lending Ranked by Dollar Amount FY13 Through 3Rd Quarter

San Francisco District Office San Francisco District Office 7(a) Lending Ranked by Dollar Amount FY13 through 3rd Quarter Lender Number of Loans Dollar Amount 1 WELLS FARGO BANK NATL ASSOC 190 $81,880,700 2 U.S. BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 97 $45,034,000 3 BRIDGE BANK NATL ASSOC 17 $26,497,800 4 FIRST COMMUNITY BANK 10 $20,491,000 5 STERLING SAVINGS BANK 15 $20,168,200 6 FOCUS BUSINESS BANK 12 $18,230,400 7 EAST WEST BANK 23 $11,166,000 8 SANTA CRUZ COUNTY BANK 13 $9,164,000 9 EXCHANGE BANK 12 $8,757,000 10 OPEN BANK 12 $8,389,800 11 LIVE OAK BANKING COMPANY 8 $8,060,000 12 COMMUNITY BANK OF THE BAY 16 $7,965,400 13 REDWOOD CU 18 $7,901,000 14 HERITAGE BANK OF COMMERCE 20 $7,739,500 15 BAY COMMERCIAL BANK 3 $7,186,900 16 JPMORGAN CHASE BANK NATL ASSOC 69 $6,531,500 17 WILSHIRE STATE BANK 9 $6,271,500 18 BANK OF THE WEST 7 $5,630,900 19 REDWOOD CAPITAL BANK 9 $5,078,000 20 NCB, FSB 2 $5,000,000 21 NEWTEK SMALL BUS. FINANCE INC. 4 $4,723,000 22 STATE BK OF INDIA (CALIFORNIA) 1 $4,460,000 23 HANMI BANK 2 $4,170,000 24 BANK OF THE ORIENT 8 $4,145,000 25 OBDC SMALL BUSINESS FINANCE 26 $3,789,200 26 COMERICA BANK 3 $3,699,900 27 PLUMAS BANK 8 $3,631,600 28 BBCN BANK 9 $3,594,000 29 CITY NATIONAL BANK 9 $3,520,000 30 UMPQUA BANK 8 $3,376,900 31 SEACOAST COMMERCE BANK 6 $3,331,300 32 HANA SMALL BUS. -

“IOLTA-Eligible” L

All of the financial institutions identified below are eligible to hold IOLTA. If your financial institution is not identified on the list below but would like to become eligible to hold an IOLTA, please call the Legal Services Trust Fund Program at the State Bar of California to determine how to become eligible. “IOLTA–Eligible” Financial Institutions 5.7.08 1st Centennial Bank City National Bank Gilmore Bank Premier Commercial Bank 1st Century Bank Coast National Bank Gold Country Bank Premier Service Bank 1st Enterprise Bank Comerica Bank Golden State Business Bank Premier Valley Bank 1st Pacific Bank of California Commerce Bank of Folsom Golden Valley Bank Premier West Bank Affinity Bank Commerce Bank of Temecula Granite Community Bank Presidio Bank Alliance Bank Valley Greater Bay Bank Private Bank of the Peninsula Alta Alliance Bank Commerce National Bank Guaranty Bank Professional Business Bank America California Bank Commerce West Bank Hanmi Bank Promerica Bank American Business Bank Commercial Bank of California Heritage Bank of Commerce Provident Bank American Continental Bank Commonwealth Business Heritage Oaks Bank Rabobank, N.A. American Premier Bank Bank HSBC Bank Redding Bank of Commerce American Principle Bank Community Bank Imperial Capital Bank Redwood Capital Bank American River Bank Community Bank of San Inland Community Bank Regents Bank American Riviera Bank Joaquin Innovative Bank River City Bank American Security Bank Community Bank of Santa International City Bank River Valley Community Bank Americas United Bank -

Preserving Minority Depository Institutions, May 2019

Preserving Minority Depository Institutions May 2019 B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S YSTEM Preserving Minority Depository Institutions May 2019 B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S YSTEM Errata The Federal Reserve revised this report on May 30, 2019. The revisions are listed below. On p. 6, under Table 2: • In column three, the column head was changed from “Total assets (millions of dollars)” to “Total assets (thousands of dollars).” On p. 15, under Table A.1: • In column five, the column head was changed from “Assets (millions of dollars)” to “Assets (thousands of dollars).” On p. 24, on Figure A.3: • The labels for the bar graphs have been reordered so that “2014 SMB” is the top label, followed by “2015 SMB,” “2016 SMB,” “2017 SMB,” and “2018 SMB.” This and other Federal Reserve Board reports and publications are available online at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/default.htm. To order copies of Federal Reserve Board publications offered in print, see the Board’s Publication Order Form (https://www.federalreserve.gov/files/orderform.pdf) or contact: Printing and Fulfillment Mail Stop K1-120 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Washington, DC 20551 (ph) 202-452-3245 (fax) 202-728-5886 (email) [email protected] iii Preface: Implementing the Dodd-Frank Act The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve efforts implementing the Dodd-Frank Act and a list System (Board) is responsible for implementing of the implementation initiatives completed by the numerous provisions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Board as well as the most significant initiatives the Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 Board expects to address in the future.1 (Dodd-Frank Act), including mandates to preserve and promote Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs). -

Department of Financial Institutions Summary of Pending Applications As of December 2012

DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS SUMMARY OF PENDING APPLICATIONS AS OF DECEMBER 2012 Assembly Bill 1301 (Gaines) Changes Procedures for Banking Office Applications AB 1301 (Gaines) became law on January 1, 2009. Among the changes made by the new law were to: Reclassify banking offices as head office, branch office and facility; Eliminate the place of business and extension of banking office categories; Eliminate the requirement that banks give advance notice to DFI before opening or relocating a banking office, or redesignating a head office and branch office. Consequently, notice of banking offices that open, relocate or are redesignated on or after January 1, 2009 will only be published after the fact. Eliminate the Miscellaneous Powers and Provisions chapter of the Financial Code that required banks receive approval to engage in certain activities, e.g., FC 752, FC 772, etc. APPLICATION TYPE PAGE NO. BANK APPLICATION CONVERSION TO STATE CHARTER 1 ACQUISITION OF CONTROL 1 MERGER 1 PURCHASE OF PARTIAL BUSINESS UNIT 2 NEW BRANCH 2 NEW FACILITY 3 HEAD OFFICE RELOCATION 3 BRANCH RELOCATION 4 DISCONTINUANCE OF BRANCH OFFICE 4 DISCONTINUANCE OF FACILITY 7 INDUSTRIAL BANK APPLICATION DISCONTINUANCE OF BRANCH OFFICE 7 PREMIUM FINANCE COMPANY APPLICATION NEW PREMIUM FINANCE COMPANY 8 HEAD OFFICE RELOCATION 8 TRUST COMPANY APPLICATION ACQUISITION OF CONTROL 9 FOREIGN (OTHER NATION) BANK APPLICATION NEW OFFICE 9 RELOCATION OF OFFICE 9 VOLUNTARY SURRENDER OF LICENSE 9 FOREIGN (OTHER STATE) BANK APPLICATION NEW FACILITY 10 DISCONTINUANCE