Mäkelä Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Work Behind the Representation a Qualitative Study on the Strategic Work of the Communicators Behind Political Social Media Accounts

The work behind the representation A qualitative study on the strategic work of the communicators behind political social media accounts. Arbetet bakom representationen En kvalitativ studie om kommunikatörers strategiska arbete bakom sociala medier. Erik Holm Andersson Linn Lyngen Humaniora Medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap 15 hp Theo Röhle 05/02-16 Abstract Social media has given politicians another platform to perform campaigning in. This essay has been a study on the relationships between politicians, social media, communicators and their mutual work behind what is published. Has this relatively new form of media channel affected the way that politicians market themselves online? How does the work behind the social media channels look, what strategies are planned behind the representation for the party leader to stand for an entire ideology with its values? The research questions of this study: - Do the strategic work from a communicator affect what is published on the politicians personal account and the official party account, and to what extent? - How do the communicators of Swedish political representatives use social media? Do they express their communication in a personalized manner or focus mainly on the professional part of their assignment? - What are the most important aspects in communicating through social media? A personalization within political campaigning has increased during the past time, much because of the new media channels working together with the traditional media channels, leaving not much to be hidden about the person that is the representative for the ideology at hand. Personalization does not mean what the person is but what qualities that this person shows. How much personalization is presented is dependent on the political climate that is in the country at hand, but this study focuses on the Swedish political climate, where personalization has become a more important part of campaigning, whether on social media or physical campaigning. -

Impact of Viral Marketing in India

www.ijemr.net ISSN (ONLINE): 2250-0758, ISSN (PRINT): 2394-6962 Volume-5, Issue-2, April-2015 International Journal of Engineering and Management Research Page Number: 653-659 Impact of Viral Marketing in India Ruchi Mantri1, Ankit Laddha2, Prachi Rathi3 1Researcher, INDIA 2Assistant Professor, Shri Vaishnav Institute of Management, Indore, INDIA 3Assistant Professor, Gujrati Innovative College of Commerce and Science, Indore, INDIA ABSTRACT the new ‘Mantra’ to open the treasure cave of business Viral marketing is a marketing technique in which success. In the recent past, viral marketing has created a lot an organisation, whether business or non-business of buzz and excitement all over the world including India. organisation, tries to persuade the internet users to forward The concept seems like ‘an ultimate free lunch’- rather a its publicity material in emails usually in the form of video great feast for all the modern marketers who choose small clips, text messages etc. to generate word of mouth. In the number of netizens to plant their new idea about the recent past, viral marketing technique has achieved increasing attention and acceptance all over the world product or activity of the organisation, get it viral and then including India. Zoozoo commercials by Vodafone, Kolaveri watch while it spreads quickly and effortlessly to millions Di song by South Indian actor Dhanush, Gangnam style of people. Zoozoo commercials of Vodafone, Kolaveri Di- dance by PSY, and Ice Bucket Challenge with a twister Rice the promotional song sung by South Indian actor Dhanush, Bucket Challenge created a buzz in Indian society. If certain Gangnam style dance by Korean dancer PSY, election pre-conditions are followed, viral marketing technique can be canvassing by Narendra Modi and Ice Bucket Challenge successfully used by marketers of business organisations. -

Unraveling the Impact of Social Media on Extremism: Implications for Technology Regulation and Terrorism Prevention

SUSARLA | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM UNRAVELING THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON EXTREMISM: IMPLICATIONS FOR TECHNOLOGY REGULATION AND TERRORISM PREVENTION This paper, part of the Legal Perspectives on Tech Series, was commissioned in ANJANA SUSARLA conjunction with the Congressional Counterterrorism Caucus SEPTEMBER 2019 UNRAVELING THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON EXTREMISM 1 SUSARLA | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM on Knowledge Discovery and Data About the Program Mining, Information Systems Research, on Extremism International Conference in Information Systems, Journal of Management Information Systems, Management The Program on Extremism at George Science and MIS Quarterly. She has Washington University provides served on and serves on the editorial analysis on issues related to violent boards of Electronic Commerce and non-violent extremism. The Research and Applications, Information Program spearheads innovative and Systems Research, MIS Quarterly and thoughtful academic inquiry, the Journal of Database Management. producing empirical work that strengthens extremism research as a Anjana Susarla has been a recipient of distinct field of study. The Program the William S. Livingston Award for aims to develop pragmatic policy Outstanding Graduate Students at the solutions that resonate with University of Texas, a Steven Schrader policymakers, civic leaders, and the Best Paper Finalist at the Academy of general public. Management, the Association of Information Systems Best Publication Award, a Runner-Up for Information About the Author Systems Research Best Published Paper Award 2012 and the Microsoft Prize by Anjana Susarla is an Associate Professor the International Network of Social at the Eli Broad School of Business, Networks Analysis Sunbelt Conference. Michigan State University. She has worked in consulting and led experiential projects with several Anjana Susarla earned an undergraduate companies. -

Diversity & Inclusion | Bleacher Talk

Black Twitter DIVERSITY & INCLUSION | BLEACHER TALK 1990s How we got here 1995 MID - LATE 90S 1999 1999 BLACK VOICES (ON AOL) MESSAGE BOARDS OKAYPLAYER NIKE TALK Before we get into it, it’s important to have some context Articles and national news Black communities began Black Twitter’s origins can Much of sneaker culture around the history of Black people and social media in the relevant to Black communities forming spontaneously on be traced back to Okayplayer, as we know it came from were launched to instant opinionated message boards where conversations about enthusiasts perusing the age of the internet fanfare, featuring now- and forums for news, sports, Blackness and Black influence Nike Talk message boards, legendary chat rooms that set celebrity gossip, fashion, started to take shape. where their passion What you’re seeing (or will see) as it relates to Black the blueprint for what we see and hair care, catering to an influenced the corporate Twitter, isn’t anything new. There have been various in Black social media. African American perspective. and fashion world. iterations of what we today consider Black twitter Chatrooms on AOL Black Voices, message boards, Myspace, to Twitter and Vine. Within these environments, 2000s safe spaces (for lack of a better term) were fostered around a all kinds of topics specific to the AA experience 2003 2004 2006 and interests. MYSPACE FACEBOOK TWITTER In its prime, MySpace Facebook reigned as a highly popular site for the Twitter’s early days felt like encouraged self-expression, African American community, but since the 2016 a whole new world that It’s not unlike how Black people have historically something African Americans elections it has developed a reputation as a breeding Black users ran toward to communicated in real world spaces within a Black are often discouraged from ground for false information. -

A Small-Scale Exploratory Study on Omani College Students’ Perception of Pragmatic Meaning Embedded in Memes

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Proceedings of 2nd MEC TESOL Conference 2020 Pp.298-313 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/MEC2.22 A Small-Scale Exploratory Study on Omani College Students’ Perception of Pragmatic Meaning Embedded in Memes Maher Al Rashdi Centre for Foundation Studies Middle East College, Muscat, Oman Email: [email protected] Abstract Memes are a viral phenomenon in the contemporary digital culture. The modern, digital definition of memes depicts them simply as pictures with texts circulated in social media platforms that tackle a particular issue in a humorous way (Chen, 2012; Rogers, 2014; Shifman, 2014). Due to its growing popularity, memes have been considered as a tool to negotiate cultural-social norms especially among teenagers (Gal, Shifman & Kampf, 2016). However, not much research has been done on memes in relation to other fields. Therefore, it is important to examine how the educational field could benefit from utilizing memes in discourse analysis and English teaching. To be more specific, the study aims at investigating the perceptions of Omani students at Middle East College of the utilizations of memes in the education. The present study seeks to answer the question: how do Omani undergraduate students perceive the use of memes inside the classroom? Primarily, data was collected through observing 29 semester three students in a higher education institute by giving them five different memes to infer their pragmatic meaning. After the observation, a short questionnaire was distributed to students to investigate their perception of memes. The findings revealed that most students were able to infer the pragmatic meanings embedded in memes. -

A Qualitative Analysis of Netflix Communication Strategy on Instagram in the United States

Instagram as a mirror of brand identities: A qualitative analysis of Netflix communication strategy on Instagram in the United States Student Name: Blagovesta Dimitrova Student Number: 494241bd Supervisor: Dr. Deborah Castro Mariño Master Media Studies - Media & Creative Industries Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master's Thesis June 2019 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ..........................................................................................................................................3 Preface ..............................................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................5 1.1 Instagram and Netflix .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Research Problem ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Scientific Relevance ............................................................................................................................ 8 1.4 Social Relevance .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Thesis Outline ..................................................................................................................................... -

An Analysis of Emotional Contagion and Internet Memes ⇑ Rosanna E

Computers in Human Behavior 29 (2013) 2312–2319 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Computers in Human Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh What makes a video go viral? An analysis of emotional contagion and Internet memes ⇑ Rosanna E. Guadagno a, , Daniel M. Rempala b, Shannon Murphy c, Bradley M. Okdie d a National Science Foundation, Division of Behavioral and Cognitive and Social Sciences, United States b Department of Psychology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, United States c Department of Psychology, University of Alabama, United States d Department of Psychology, Ohio State University at Newark, United States article info abstract Article history: What qualities lead some Internet videos to reach millions of viewers while others languish in obscurity? This question has been largely unexamined empirically. We addressed this issue by examining the role of emotional response and video source on the likelihood of spreading an Internet video by validating the Keywords: emotional response to an Internet video and investigating the underlying mechanisms. Results indicated Emotional contagion that individuals reporting strong affective responses to a video reported greater intent to spread the Internet video. In terms of the role of the source, anger-producing videos were more likely to be forwarded but Groups only when the source of the video was an out-group member. These results have implications for emo- Memes tional contagion, social influence, and online behavior. Contagion Social influence Published by Elsevier Ltd. 1. Introduction of a candidate’s character defect (e.g., dishonest, ‘‘flip-flopper’’) or to provide amusing footage of a specific campaign or candidate. -

Meme As Political Criticism Towards 2019 Indonesian General Election: a Critical

239 | Studies in English Language and Education, 6(2), 239-250, 2019 Meme as Political Criticism towards 2019 Indonesian General Election: A Critical Discourse Analysis P-ISSN 2355-2794 E-ISSN 2461-0275 Hesti Raisa Rahardi* Rosaria Mita Amalia Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Cultural Science, Universitas Padjadjaran, Sumedang, Jawa Barat 45363, INDONESIA ABstract This study aims to investigate the memes created by Nurhadi-Aldo, a Fictional presidential candidate. Data is collected From Nurhadi-Aldo’s Instagram profile. The descriptive qualitative approach was used and the sampling procedure carried out was purposive sampling. To analyze the data and to uncover the hidden values, the three-dimension analysis proposed by Fairclough (2001) was used. The First dimension was textual analysis where the textual and visual sign of the presidential memes were examined. The second dimension was the analysis of the discursive practice surrounding the production of Nurhadi-Aldo memes. And the last was the sociocultural practice analysis that deals with how Indonesian internet users reacted to this viral phenomenon. The result points out that the memes represent the visualization of public social critics toward a political condition in Indonesia. With regards to the content creator, Nurhadi-Aldo’s memes Further indicate the scepticism value of Indonesian youth. These Findings Further confirm that the Function of the meme is not limited to entertainment purpose only, but also to deliver political criticism. Hence, it is expected that the Findings will give more insights into how certain values can be delivered through the use of everyday text, such as memes. Keywords: CDA, Fairclough’s framework, memes, fictional candidates, hidden values. -

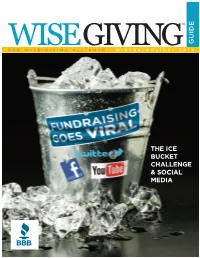

The Ice Bucket Challenge and Social Media

TM GUIDE WISEBBB WISE GIVING ALLIANCEGIVING : WINTER/HOLIDAY 2014 THE ICE BUCKET CHALLENGE & SOCIAL MEDIA ® INSIDE New Study on 7 Charity Trust 2 How to Read the 8 List of National ® Fundraising Charities Goes Viral: Q&A about the 51 The Ice Bucket Challenge Wise Giving & Social Media Guide A Publication of the BBB Wise Giving Alliance National Charity 51 10 Seal Program Standards 52 List of Nationally for Charity Soliciting Charities Accountability The Wise Giving Guide is published three times a year to help donors make more BBB Wise Giving Alliance Board of Directors informed giving decisions. This Myrl Weinberg – Chair Rick Johnston guide includes a compilation of President, National Health Council Vice President, ICF Interactive the latest evaluation conclusions Washington, DC Glen Allen, VA completed by the BBB Wise Cass Wheeler – Vice Chair Andras Kosaras Giving Alliance. Strategic Consultant/Coach/Speaker Arnold & Porter LLP Georgetown, TX (former CEO, American Washington, DC Heart Association) If you would like to see a Paulette Maehara particular topic discussed Mark Shamley – Treasurer President (retired) President, Association of Corporate Association of Fundraising Professionals in this guide, please email Contributions Professionals • Orlando, FL suggestions to Char Mollison [email protected] Audrey Alvarado – Secretary Faculty and Program Coordinator Alvarado Consulting Nonprofit Management Program, or write to us at the (former Vice President, Nonprofit Johns Hopkins University • Washington, DC address below. Roundtable of Greater Washington) Patrick Rooney Washington, DC Executive Director, Center on Philanthropy at WINTER/HOLIDAY ISSUE 2014 Holly Cherico Indiana University • Indianapolis, IN Director, Marketing & Communications, Claire Rosenzweig BBB Wise Giving Alliance The Kingsbury Center • Washington, DC President, BBB/Metropolitan New York 3033 Wilson Blvd. -

Going 'Viral' on Social Media: a Study of Popular Videos on Facebook

Amity Journal of Media & Communication Studies (ISSN 2231 – 1033) Copyright 2016 by ASCO 2016, Vol. 6, No. 2 Amity University Rajasthan Going ‘Viral’ on Social Media: A Study of Popular Videos on Facebook Prof. Archana R Singh Ishrat Singh Punjab University, India Abstract This study identifies ‘viral’ videos shared on official Facebook pages of three top leaders of Punjab, the state that is set to go for assembly elections in early 2017.Once the videos are identified, they will be analysed for various elements in the content. This study uses multi stage sampling process. In the first stage, the three top politicians belonging to three major parties are identified. The official Facebook pages of the selected political leaders are chosen as the universe of the study. The results of this study show that internet is not as effective a medium to reach the masses as far as the popular perception go because having large number of ‘views’ or ‘likes’ does not translate into a simple gesture such as ‘share’ in order for a video message to go viral. Keywords: viral, social media, political sphere,video Introduction With the world increasingly going digital and political campaigns being driven online, one finds every political party trying hard to join the bandwagon and register an online presence. We have witnessed the phenomenon in the 2014 General Elections in India and are also witnessing it in the Presidential Race in the USA. The phenomenon is true not just for national level election campaigns but is evident in the assembly elections as well. This paper casts a look at the Punjab Assembly election scenario as the race to go ‘viral’ is on. -

The Supernatural Media Virus Virus Anxiety in Gothic Fiction Since 1990

From: Rahel Sixta Schmitz The Supernatural Media Virus Virus Anxiety in Gothic Fiction Since 1990 July 2021, 290 p., pb., 5 b&w ill., 54 col. ill. 44,00 € (DE), 978-3-8376-5559-9 E-Book: PDF: 43,99 € (DE), ISBN 978-3-8394-5559-3 Since the 1990s, the virus and the network metaphors have become increasingly pop- ular, finding application in a broad range of everyday discourses, academic disciplines, and fiction genres. In this book, Rahel Sixta Schmitz defines and discusses a trope recurring in Gothic fiction: the supernatural media virus. This trope comprises the confluence of the virus, the network, and a deep, underlying media anxiety. This study shows how Gothic narratives such as House of Leaves or The Ring feature the super- natural media virus to negotiate as well as actively shape imaginations of the network society and the dangers of a globalized, technologized world. Rahel Sixta Schmitz, born in 1991, earned her doctorate in cultural studies at the Justus Liebig University in Giessen, Germany in 2020. Her research focuses on Gothic fic- tion across all narrative media, especially Gothic in the late twentieth and twenty-first century. For further information: www.transcript-verlag.de/en/978-3-8376-5559-9 © 2021 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Contents Acknowledgments............................................................9 Introduction: The Age of Virus Anxiety ...................................... 11 1. The Virus, the Network, and the Supernatural Media Virus ............ 39 1.1 Theories of Metaphor .................................................. 39 1.2 The Viral Metaphor: The Spread of the Virus Across Disciplines ......... 44 1.3 The Ubiquity of the Network Metaphor and the Emergence of the Network Society .................................................. -

No Ice Bucket Challenge’Adapted from an Original and Article by Willpiles Oremus of on Likes in Return

To be used in answering S ecTion 4 – MeDiA STUDIES Take the ‘NoEDIT oIceRIAL Bucket CoMMENT Challenge’ acebook has become saturated with videos of people dumping buckets of ice on their heads. They’re taking the ‘Ice Bucket Challenge’, a viral phenomenon whose apparent purpose is to raise moneyF for charity. Yet it’s hard to shake the feeling that, for most of the people posting ice bucket videos of themselves on Facebook, Vine and Instagram, the charity part remains a postscript. Remember, the way the challenge is set up, the ice-drenching is the alternative to contributing actual money. Some of the people issuing the challenge have tweaked the rules by asking people to contribute money even if they do soak themselves. Even so, a lot of the participants are probably spending more money on bagged ice than on the Do not fetch a bucket, fill it with ice, or charity concerned. dump it on your head. As for ‘raising awareness’, few of the Do not film yourself or post anything on videos I’ve seen contain any substantive social media. information about the charity, why the money is needed, or how it will be used. Just donate the money and feel free to More than anything else the ice bucket politely encourage your friends and videos feel like an exercise in raising family to do the same. awareness of one’s own zaniness and/or Congratulations! Not only have you attractiveness. Watch some videos and contributed to a good cause but you’ve you’ll see the stunt is really just about done your part for the environment by getting friends to film themselves doing conserving the energy and fresh water something dumb for no reason.