1 Prologue 1. the Servian Wall Was Constructed During the Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Ritual Cleaning-Up of the City: from the Lupercalia to the Argei*

RITUAL CLEANING-UP OF THE CITY: FROM THE LUPERCALIA TO THE ARGEI* This paper is not an analysis of the fine aspects of ritual, myth and ety- mology. I do not intend to guess the exact meaning of Luperci and Argei, or why the former sacrificed a dog and the latter were bound hand and foot. What I want to examine is the role of the festivals of the Lupercalia and the Argei in the functioning of the Roman community. The best-informed among ancient writers were convinced that these were purification cere- monies. I assume that the ancients knew what they were talking about and propose, first, to establish the nature of the ritual cleanliness of the city, and second, see by what techniques the two festivals achieved that goal. What, in the perception of the Romans themselves, normally made their city unclean? What were the ordinary, repetitive sources of pollution in pre-Imperial Rome, before the concept of the cura Urbis was refined? The answer to this is provided by taboos and restrictions on certain sub- stances, and also certain activities, in the City. First, there is a rule from the Twelve Tables with Cicero’s curiously anachronistic comment: «hominem mortuum», inquit lex in duodecim, «in urbe ne sepelito neve urito», credo vel propter ignis periculum (De leg. II 58). Secondly, we have the edict of the praetor L. Sentius C.f., known from three inscrip- tions dating from the beginning of the first century BC1: L. Sentius C. f. pr(aetor) de sen(atus) sent(entia) loca terminanda coer(avit). -

Template for the EFS-Liu Conference

Paper from the Conference “INTER: A European Cultural Studies Conference in Sweden”, organised by the Advanced Cultural Studies Institute of Sweden (ACSIS) in Norrköping 11-13 June 2007. Conference Proceedings published by Linköping University Electronic Press at www.ep.liu.se/ecp/025/. © The Author. Assessing the ‘Fascist Filter’ and its Legacy* Frederick Whitling Department of History and Civilisation, European University Institute, Italy [email protected] The extensive physical alterations to the city of Rome in the Fascist period have arguably created what I refer to as a ‘Fascist filter’, which will be tentatively discussed here. This paper investigates perceptions of what I refer to as “low status ruins” from antiquity in the modern city of Rome, focusing on the Servian wall in the context of the Termini train station in Rome. What are the possible functions, meanings, and practical implications of ruins in a modern cityscape? How are they ‘remembered’ or envisaged as (classical) heritage? I will in the following tentatively discuss the possible contextual value of Ancient ruins in Rome, focusing on the legacy of the ‘Fascist filter’. * This paper is based on an oral presentation, hence the absence of references. 645 Introduction The normative ‘master narrative’ of Ancient Greece and Rome as the foundation on which Western civilisation rests, incarnated in the classical tradition, still implies that we ‘understand’ antiquity, that there are ‘direct channels’ (tradition) through which ‘we’ (as Europeans) are in direct contact with ‘our’ past. The complexity of classical tradition and what I have chosen to call the ‘Fascist filter’ arguably rule out the possibility of such comprehension. -

Percorsi Bici Depliant

The bicycle represents an excel- lent alternative to mobility-based travel and sustainable tourism. The www.turismoroma.it Eternal City is still unique, even by some bicycle. There are a total of 240 km INFO 060608 of cycle paths in Rome, 110 km of useful info which are routed through green areas, while the remainder follow public roads. The paths follow the courses of the Tiber and Aniene rivers and along the line of the coast at Ostia. Bicycle rental: Bike sharing www.gobeebike.it www.o.bike/it Casa del Parco Vigna Cardinali Viale della Caffarella Access from Largo Tacchi Venturi for information and reservations, call +39 347 8424087 Appia Antica Service Centre Via Appia Antica 58/60 stampa: Gemmagraf Srl - copie 5.000 10/07/2018 For information and reservations, call +39 06 5135316 www.infopointappia.it Rome by bike communication Valley of the Caffarella The main path of the Valley of the Caffarella, scene of myths and legends intertwined with the history of Rome, features a wide range of biodiversity as well as important historical heritage, such as a part of the Triopius of Herod Atticus. Entering the park via the Via Latina entrance in correspondence with Largo Tacchi e Venturi, head right up to Via della Caffarella and follow the path to the Appia Antica, approxima- tely 6 km away. Along the way you'll encounter: the Casale della Vaccareccia, consisting of a medieval tower and a sixteenth century farmhouse, built by Caffarelli who, in the sixteenth century, reclaimed the area; the Sepolcro di Annia Regilla, a sepulchral monument shaped like a small temple, and the meandering Almone river, a small tributary of the Tiber, thought to be sacred by the ancient Romans. -

Rome's Busy Streets

SPRING 2008 VOLUME III, ISSUE 1 THE FORUM ROMANUM News from the University of Dallas Eugene Constantin Rome Campus at Due Santi A.D. 79: Spring Romers on the Bay of Naples In early February, the Spring ‘08 Rome students packed their bags and boarded buses in preparation for a trip to the Bay of Naples. The overnight junket, led by faculty and staff, was meant to introduce students to the kind of educational travel that so enhances classroom studies on the Rome Campus by providing an opportunity to explore the region’s abundance of Greco-Roman art and history. The bus ride to Naples provided a magnificent view of the volcano Vesuvius (see photo above)—a reminder that the mountain’s eruption in A.D. 79 rocked the Roman world and destroyed cities like Pompeii and Herculaneum. Once in Naples, the first stop was at the National Archaeological Museum for a visit to its renowned antiquities collection. Under the guidance of Rome faculty, students spent the afternoon studying art and objects from the ancient world, in particular those frescoes, mosaics, and objects of daily life recovered from excavations at Pompeii. Departing Naples, the group headed further south to the seaside town of Castellamare di Stabiae, where they checked into rooms at the Vesuvian Institute just in time to enjoy a spectacular sunset across the Bay of Naples. The evening brought a bountiful meal and a spectacular performance of music on ancient instruments. The next day was spent in the ancient city of Pompeii. Covered by pumice and ash when Vesuvius erupted, the city was redis- covered in the middle of the eighteenth century and is still under excavation. -

• Late Roman Empire • Germanic Invasions • Emperor Constantine • Christianity LATE ROMAN EMPIRE

• Late Roman Empire • Germanic invasions • Emperor Constantine • Christianity LATE ROMAN EMPIRE MEDITERRANEAN as MARE NOSTRUM = our sea GERMANIC INVASIONS OF 3rd CENTURY AD 250-271 271 Aurelian wall in red Servian wall in black AURELIAN WALL 271 AD built by Emperor Aurelian for defense of city against German invaders Military revolution of 3rd Century begins with temporary measures under Marcus Aurelius: resorts to conscription of slaves, gladiators, criminals, barbarians (Germans) Septimus Severus 193-211 opens Praetorian Guard to Germans increasing militarization, rise in taxes rise of provincials and Germans in army: Diocletian: son of freedman from Dalmatia social revolution in army and ruling class Diocletian 284-305 TETRARCHY 284-305 AD “rule of four” DIOCLETIAN’S REORGANIZATION OF EMPIRE: Motives: 1) military defense of frontiers 2) orderly succession Four rulers: two Augusti (Diocletian as Senior Augustus) they choose two Caesars (adopted successors, not their own sons) Four Prefectures and four capitals: none at Rome WHERE IS ROME? Four Prefectures and their capitals: GAUL ITALY ILLYRICUM ASIA | Capitals: | | | Trier Milan Sirmium Nicomedia (near Belgrade) (on Bosphorus Straits near Byzantium) Imperial government under Diocletian: 4 prefectures, each divided into 12 dioceses, which are then divided into 100 provinces for local government and tax collection Western Empire: capitols – Trier and Milan Eastern Empire: capitols – Sirmium and Nicomedia DIOCLETIAN’S DIVISION OF EMPIRE INTO 12 DIOCESES • Four Prefectures and their capitals: (none at Rome) • GAUL ITALY ILLYRICUM ASIA • Capitals: | | | • Trier Milan Sirmium Nicomedia (near Belgrade) (on Bosphorus near Byzantium) • Rulers: West East Senior Caesar Augustus Augustus Caesar Constantius Maximian Diocletian Maximianus | | (abdicate in 305 AD) Son Son | | Constantine Maxentius PALACE OF DIOCLETIAN, SPLIT (modern Croatia) Split (in modern Croatia) site of Diocletian’s palace BATHS OF DIOCLETIAN, ROME Basilica of San Marco Venice 11-12th C. -

Ancient Roman Tour Walk with the Ancient Romans TOUR DIFFICULTY EAZY MEDIUM HARD

SHORE EXCURSION BROCHURE FROM THE PORT OF ROME DURATION 10 hr Ancient Roman Tour Walk With The Ancient Romans TOUR DIFFICULTY EAZY MEDIUM HARD our driver will pick you up at your cruise ship for an experience of a lifetime. YYour Own Italy’s Private Rome shore excursion of Ancient Rome includes the Colosseum, Appian Way, Pantheon, Ancient Rome Forum and much more. Ideal for families and those looking for an in-depth and thoroughly entertaining tour focusing on the life and times of Ancient Romans. First, with your private English-speaking guide, visit the alluring remains of the Ancient Roman Forum. While walking through the ruins of the imposing ancient buildings, you will lis- ten to its history -- peppered with anecdotes about the structure of Roman so- ciety, their beliefs, their social and political life. Learn how the Romans managed to create and control such a vast territory and how that empire declined. hen, avoiding the lines to get in to the Colosseum, you’ll visit the imposing Tarena and relive the days of Ancient Rome! Enjoy a thorough tour of the building, learning about the inner workings of the Colosseum and the special effects and showmanship of the ferocious games played there…the role the Col- osseum had in Roman society…and what it meant to a Roman to attend these games…what different games where held in the amphitheater. Afterwards, you will be taken on a short drive through the center of Rome to see the Pantheon, and learn about the rich history of one of Rome’s most important and beautiful buildings. -

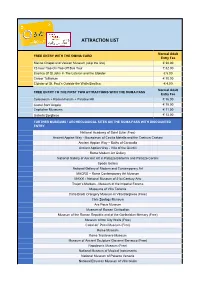

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Appius Claudius Caecus 'The Blind'

Appius Claudius Caecus ‘The Blind’ Faber est quisquis suae fortunae (‘Every man is architect of his own fortune’) Appius Claudius Caecus came from the Claudian gens, a prime patrician family that could trace its ancestors as far back as the decemvirs who authored Rome’s first laws (the Twelve Tables) in the mid-fifth century BC. Although many Roman families could boast successful ancestors, Appius Claudius Caecus has the distinction of being one the first characters in Roman history for whom a substantial array of material evidence survives: a road, an aqueduct, a temple and at least one inscription. His character and his nickname Caecus, ‘The Blind’, are also explained in historical sources. Livy (History of Rome 9.29) claims he was struck down by the gods for giving responsibilities of worship to temple servants, rather than the traditional family members, at the Temple of Hercules. Perhaps a more credible explanation is offered by Diodorus Siculus (20.36), who suggests that Appius Claudius said he was blind and stayed at home to avoid reprisals from the Senate after his time in office. In that case, his name was clearly coined in jest, as is often the case with cognomen. Appius Claudius Caecus, whether or not he was actually blind, is an illuminating case study in the ways that varying types of evidence (literature, inscriptions and archaeology) can be used together to recreate history. His succession of offices, not quite the typical progression of the cursus honorum, records a man who enjoyed the epitome of a successful career in Roman politics (Slide 1). -

Unfolding Rome: Giovanni Battista Piranesi╎s Le Antichit〠Romane

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Unfolding Rome: Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Le Antichità Romane, Volume I (1756) Sarah E. Buck Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE, AND DANCE UNFOLDING ROME: GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI’S LE ANTICHITÀ ROMANE, VOLUME I (1756) By Sarah E. Buck A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sarah Elizabeth Buck defended on April 30th, 2008. ____________________________________ Robert Neuman Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Lauren Weingarden Committee Member ____________________________________ Stephanie Leitch Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________________ Richard Emmerson, Chair, Department of Art History ____________________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis grew out of a semester paper from Robert Neuman’s Eighteenth-Century Art class, one of my first classes in the FSU Department of Art History. Developing the paper into a larger project has been an extremely rewarding experience, and I wish to thank Dr. Neuman for his continual guidance, advice, and encouragement from the very beginning. I am additionally deeply grateful for and appreciative of the valuable input and patience of my thesis committee members, Lauren Weingarden and Stephanie Leitch. Thanks also go to the staff of the University of Florida-Gainesville’s Rare Book Collection, to Jack Freiberg, Rick Emmerson, Jean Hudson, Kathy Braun, and everyone else who has been part of my graduate school community in the Department of Art History. -

The Discovery and Exploration of the Jewish Catacomb of the Vigna Randanini in Rome Records, Research, and Excavations Through 1895

The Discovery and Exploration of the Jewish Catacomb of the Vigna Randanini in Rome Records, Research, and Excavations through 1895 Jessica Dello Russo “Il cimitero di Vigna Randanini e’ il punto di partenza per tutto lo studio della civilta’ ebraica.” Felice Barnabei (1896) At the meeting of the Papal Commission for Sacred Archae- single most valuable source for epitaphs and small finds from ology (CDAS) on July 21,1859, Giovanni Battista de Rossi the site.6 But the catacomb itself contained nothing that was of strong opinion that a newly discovered catacomb in required clerical oversight instead of that routinely performed Rome not be placed under the Commission’s care.1 Equally by de Rossi’s antiquarian colleagues at the Papal Court. surprising was the reason. The “Founder of Christian Archae- On de Rossi’s recommendation, the CDAS did not assume ology” was, in fact, quite sure that the catacomb had control over the “Jewish” site.7 Its declaration, “la cata- belonged to Rome’s ancient Jews. His conclusions were comba non e’ di nostra pertinenza,” became CDAS policy drawn from the very earliest stages of the excavation, within for the next fifty years, even as three other Jewish cata- sight of the catacombs he himself was researching on the combs came to light in various parts of Rome’s suburbium.8 Appian Way southeast of Rome. They would nonetheless In each case, the discovery was accidental and the excava- determine much of the final outcome of the dig. tion privately conducted: the sites themselves were all even- The CDAS had been established just a few years before in tually abandoned or destroyed. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR ....