Efficiency and Resilience of Forage Resources and Small Ruminant Production to Cope Edited By: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

280-JMES-4281-Amakrane.Pdf

Journal(of(Materials(and(( J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2018, Volume 9, Issue 9, Page 2549-2557 Environmental(Sciences( ISSN(:(2028;2508( CODEN(:(JMESCN( http://www.jmaterenvironsci.com ! Copyright(©(2018,((((((((((((((((((((((((((((( University(of(Mohammed(Premier(((((( (Oujda(Morocco( Mineralogical and physicochemical characterization of the Jbel Rhassoul clay deposit (Moulouya Plain, Morocco) J. Amakrane1,2*, K. El Hammouti1, A. Azdimousa1, M. El Halim2,3, M. El Ouahabi2, B. Lamouri4, N. Fagel2 1Laboratoire des géosciences appliquées (LGA), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université Mohammed Premier, BP 717 Oujda, Morocco 2UR Argile, Géochimie et Environnement sédimentaires (AGEs), Département de Géologie, Quartier Agora, Bâtiment B18, Allée du six Août, 14, Sart-Tilman, Université de Liège, B-4000, Belgium 3Laboratoire de Géosciences et Environnement (LGSE), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université Cadi Ayyad, BP 549 Marrakech, Morocco 4Laboratoire Géodynamique et Ressources Naturelles(LGRN), Département de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences de la Terre, Université Badji Mokhtar-Annaba, Algeria. Received 26 Jan 2018, Abstract Revised 08 Jun 2018, This study aims at the mineralogical and physicochemical characterization of clays of Accepted 10 Jun 2018 the Missour region (Boulemane Province, Morocco). For this, three samples were collected in the Ghassoul deposit. The analyses were carried by X-ray diffraction Keywords (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The thermal analysis from 500 to1100°C was also performed on studied samples, and the !!Clay, fired samples were characterized by XRD and SEM. The XRD results revealed that raw !!Ghassoul, Ghassoul clay consists mainly of Mg-rich trioctahedral smectite, stevensite-type clay, !!Characterization, which represents from 89% to 95% of the clay fraction, with a small amount of illite !!Stevensite, and kaolinite. -

Circulating Species of Leishmania at Microclimate Area Of

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Hmamouch et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:100 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2032-9 RESEARCH Open Access Circulating species of Leishmania at microclimate area of Boulemane Province, Morocco: impact of environmental and human factors Asmae Hmamouch1,2*, Mahmoud Mohamed El Alem1,3, Maryam Hakkour1,3, Fatima Amarir4, Hassan Daghbach5, Khalid Habbari6, Hajiba Fellah1,3, Khadija Bekhti2 and Faiza Sebti1,6 Abstract Background: Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is widely distributed in Morocco where its geographical range and incidence are related to environmental factors. This study aimed to examine the impact of several factors on the distribution of CL in Boulemane Province, which is characterized by several microclimates, and to identify the Leishmania species circulating in these areas. Methods: Ordinary least squares regression (OLSR) analysis was performed to study the impact of poverty, vulnerability, population density, urbanization and bioclimatic factors on the distribution of CL in this province. Molecular characterization of parasites was performed using a previously described PCR-RFLP method targeting the ITS1 of ribosomal DNA of Leishmania. Results: A total of 1009 cases were declared in Boulemane Province between the years 2000 and 2015 with incidences fluctuating over the years (P = 0.007). Analyzing geographical maps of the study region identified four unique microclimate areas; sub-humid, semi-arid, arid and Saharan. The geographical distribution and molecular identification of species shows that the Saharan microclimate, characterized by the presence of Leishmania major was the most affected (47.78%) followed by semi-arid area where Leishmania tropica was identified in three districts. -

Recueil Des Textes Juridiques Régissant Le Secteur Agricole Pour L’Année 2010

Royaume du Maroc Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche Maritime -------------------------- Direction des Affaires Administratives et Juridiques Editions Juridiques de l’Agriculture. 2011 Mars Nº5. l’Agriculture. de Juridiques Editions Recueil des Textes Juridiques Régissant le Secteur Agricole pour l’année 2010 Cellule d’Information Juridique Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche Maritime Direction des Affaires Administratives et Juridiques Av. Hassan II, Km 4 Route de Casablanca. Rabat Tél 05.37.69.02.15/16 Fax. 05.37.69.84.01 1 SOMMAIRE PAGES I- ORGANISATION, ATTRIBUTION ET RESSOURCES HUMAINES 1.1-Organisation administrative 3 1.2-Commissions paritaires 3 1.3- Nomination des sous ordonnateurs 3 II- AMENAGEMENT DE L’ESPACE AGRICOLE ET STRUCTURES FONCIERES 2.1- Réforme foncière 5 2.2- Opérations cadastrales et immatriculation 22 III- PRODUCTION AGRICOLE 3.1-Production agricole, végétale et animale 25 3.2-Mandats sanitaires 32 IV-CONTROLE DE QUALITE ET SECURITE SANITAIRE 4.1-Contrôle des obtentions, inscriptions de nouvelles variétés au 35 catalogue officiel et homologation des normes marocaines 4.2-Contrôle de la qualité et sécurité sanitaire des aliments 35 V- SYSTEME DES INCITATIONS AGRICOLES ET FISCALITE 5.1-Incitations financières 37 5.2-Incitations fiscales 40 VI- ENSEIGNEMENT, FORMATION ET RECHERCHE 41 2 Arrêté du Ministre de l'Agriculture et de la I- ORGANISATION, pêche maritime n° 244-10 du 30 safar ATTRIBUTION ET 1431 (15/02/2010) portant désignations des représentants de l'administration et RESSOURCES HUMAINES des fonctionnaires auprès commissions 1-1 Organisation administrative paritaires spécialisées centrales auprès du personnel du Ministre de l'agriculture de Décret n° 2-10-011 du 30 rabii I 1437 la pêche maritime (secteur de (17/03/2010) pris pour l'application de l'agriculture). -

Dossier Salubrité Et Sécurité Dans Les Bâtiments : Quel Règlement ?

N°30 / Mars 2015 / 30 Dh Dossier Salubrité et Sécurité dans les bâtiments : Quel règlement ? Architecture et Urbanisme L’urbanisme dans les 12 régions: Quelle vision ? Décoration d’Intérieur et Ameublement Cuisine: Quelles tendances déco 2015? Interview: Salon Préventica International : Une 2ème édition qui promet un grand nombre de Eric Dejean-Servières, commissaire nouveautés général, du salon Préventica International Casablanca Édito N°30 / Mars 2015 / 30 Dh Dossier Salubritéles et bâtiments Sécurité :dans Jamal KORCH Quel règlement ? Architecture et Urbanisme L’urbanisme dans les 12 régions: Quelle vision ? Décoration d’Intérieur et Ameublement Cuisine: Quelles tendances déco 2015? L’aménagement du territoire et le découpage Interview: Salon Préventica International : Une 2ème édition administratif : Y a-t-il une convergence ? qui promet un grand nombre de nouveautés al Eric Dejean-Servières,Casablanca commissaire général, du salon Préventica Internation e pas compromettre les n 2-15-40 fixant à 12 le nombre des Directeur de la Publication besoins des générations régions, leur dénomination, leur chef- Jamal KORCH futures, prendre en compte lieu, ainsi que les préfectures et les l’ensemble des efforts provinces qui les composent. Et sur ce Rédacteur en Chef N environnementaux des activités tracé que l’aménagement du territoire Jamal KORCH urbaines, assurer l’équilibre entre aura lieu en appliquant le contenu des [email protected] les habitants de la ville et ceux de différents documents y afférents. GSM: 06 13 46 98 92 la campagne, -

Intake of Plants Containing Secondary Compounds

Intake of plants containing secondary compounds by sheep grazing rangelands in the province of Boulemane (Morocco) Noor-Ehsan Mohammad Gobindram, Asma Boughalmi, Charles-Henri Moulin, Michel Meuret, Abdelilah Araba, Magali Jouven To cite this version: Noor-Ehsan Mohammad Gobindram, Asma Boughalmi, Charles-Henri Moulin, Michel Meuret, Ab- delilah Araba, et al.. Intake of plants containing secondary compounds by sheep grazing rangelands in the province of Boulemane (Morocco). Options Méditerranéennes. Série A : Séminaires Méditer- ranéens, Jun 2014, Clermont-Ferrand, France. 850 p. hal-01499053 HAL Id: hal-01499053 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01499053 Submitted on 30 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Intake of plants containing secondary compounds by sheep grazing rangelands in the province of Boulemane (Morocco) N-E. Gobindram1, A. Boughalmi2, C.H. Moulin1, M. Meuret1, A. Araba2 and M. Jouven1 1 SupAgro – INRA - CIRAD, UMR868 SELMET, 2 place Pierre Viala, F-34060 Montpellier, France 2 IAV Hassan II, Rabat (Morocco) Abstract. Understanding the feeding choices of ruminants grazing PSC-containing pastures can help designing pastoral management strategies which stimulate the consumption of rangeland vegetation, while preserving its biodiversity and regeneration potential. -

The World Bank Group

Document of The World Bank Group FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD1026 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$125 MILLION AND A PROPOSED LOAN FROM THE CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND IN THE AMOUNT OF US$23.95 MILLION TO THE OFFICE NATIONAL DE L’ELECTRICITE ET DE L’EAU POTABLE (ONEE) WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized CLEAN AND EFFICIENT ENERGY PROJECT APRIL 3, 2015 Energy and Extractives Global Practice Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank Group authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange Rate Effective February 28, 2015 Currency Unit = Moroccan Dirham (MAD) 9.65 MAD = US$1 US$1.42 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADEREE Agence Nationale pour le Développement des Énergies Renouvelables et de l’Efficacité Énergétique (National Agency for Renewable Energy Development and Energy Efficiency) AMI Advanced Metering Infrastructure BOT Build-Operate-Transfer CCGT Combined Cycle Gas Turbine CFL Compact Fluorescent Lamp CO2 Carbon Dioxide CPS Country Partnership Strategy CSP Concentrated Solar Power CTF Clean Technology Fund CTF IP Clean Technology Fund Investment Plan DPL Development Policy Loan DSM Demand Side Management -

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Morocco: Psychosocial Burden and Simplified Diagnosis

Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Morocco: psychosocial burden and simplified diagnosis Issam BENNIS ISBN n° 978-90-5728-583-7 Legal deposit number D/2018/12.293/11 Cover design by Anita Muys (UA media service) Description of cover photo The cover photo shows a 6-month-old facial lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a 7-year-old child living in the northern part of Morocco. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Morocco: psychosocial burden and simplified diagnosis Cutane leishmaniase in Marokko: psychosociale belasting en vereenvoudigde diagnose Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Antwerp Issam BENNIS Promoters: Co-promoters: Prof. Dr. Jean-Claude Dujardin Prof. Dr. Vincent De Brouwere University of Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp Prof. Dr. Marleen Boelaert Prof. Dr. Hamid Sahibi Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp Agricultural and Veterinary Institute Rabat Antwerp – April 17th, 2018 Individual Doctorate Committee: Chair: Prof. Dr. Luc Kestens University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium Members: Prof. Dr. Louis Maes University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium Prof. Dr. Jean-Claude Dujardin University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium Prof. Dr. Marleen Boelaert Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium External Jury Members: Prof. Dr. François Chappuis Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Zwitzerland Dr. José Antonio Ruiz Postigo World Health Organisation, Geneva, Zwitzerland Internal Jury Members: -

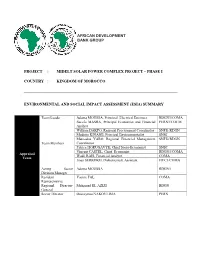

Midelt Solar Power Complex Project – Phase I

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : MIDELT SOLAR POWER COMPLEX PROJECT – PHASE I COUNTRY : KINGDOM OF MOROCCO ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) SUMMARY Team Leader Adama MOUSSA, Principal Electrical Engineer RDGN1/COMA Succès MASRA, Principal Economist and Financial PERN1/COCM Analyst William DAKPO, Regional Procurement Coordinator SNFI1/RDGN Modeste KINANE, Principal Environmentalist SNSC Mamadou YARO, Regional Financial Management SNFI2/RDGN Team Members Coordinator Patrice HORUGAVYE, Chief Socio-Economist SNSC Vincent CASTEL, Chief Economist RDGN1/COMA Appraisal Wadii RAIS, Financial Analyst, COMA Team Iman SERROKH, Disbursement Assistant FIFC3/COMA Acting Sector Adama MOUSSA RDGN1 Division Manager Resident Yacine FAL COMA Representative Regional Director- Mohamed EL AZIZI RDGN General Sector Director Ousseynou NAKOULIMA PERN 1 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) SUMMARY Project : Noor Midelt Solar Power Complex – Phase I Project No.: P-MA-FF0-004 Country: Kingdom of Morocco Department: Category: 1 Introduction This document is a summary of the Framework Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the NOOR Midelt Solar Power Complex Project - Phase I. The detailed design of the NOOR Midelt project’s power plants will be provided by the projects selected following an international competitive bidding, which explains why this assessment is a framework ESIA covering: (i) the entire site and related infrastructure (water and road infrastructure, power supply for water infrastructure (22kv line); and (ii) all the different technological options. Following their selection, the developers will submit specific ESIA/ESMP for each power plant, taking into account the specificities of each plant and will be based on the specific proposal of the developer to whom the project has been awarded. -

The State of Local Democracy in the Arab World: a Regional Report an Approach Based on National Reports from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Yemen

The State of Local Democracy in the Arab World: A Regional Report An Approach Based on National Reports from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Yemen The State of Local Democracy in the Arab World: A Regional Report An Approach Based on National Reports from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Yemen Compiled and edited by Ayman Ayoub International IDEA Participating organizations Al Urdun Al Jadid Research Centre (UJRC), Jordan The Parliamentary Think Tank (PTT), Egypt The Moroccan Association for Solidarity and Development (AMSED) The Human Rights Information and Training Centre (HRITC), Yemen This report was prepared as part of a project on the state of local democracy in the Arab world, which was funded by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID). International IDEA resources on Political Participation and Representation The State of Local Democracy in the Arab World: A Regional Report © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), 2010 This report is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this Report do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council of Member States, or those of the donors. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Strömsborg SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46-8-698 37 00 Fax: +46-8-20 24 22 Email: [email protected] Website: www.idea.int Design and layout by: Turbo Design, Ramallah Printed by: Bulls Graphics, Sweden Cover design by: Turbo Design, Ramallah ISBN: 978-91-85724-77-2 The contents of this report were prepared as part of a project on the assessment of the state of democracy at the local level in the Arab world, funded by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID). -

Annotated List of Wetlands of International Importance Morocco

Ramsar Sites Information Service Annotated List of Wetlands of International Importance Morocco 38 Ramsar Site(s) covering 316,086 ha Aguelmams Sidi Ali - Tifounassine Site number: 1,468 | Country: Morocco | Administrative region: Ifrane Area: 600 ha | Coordinates: 33°07'N 05°03'W | Designation dates: 15-01-2005 View Site details in RSIS Aguelmams Sidi Ali - Tifounassine. 15/01/05; Ifrane, Khénifra; 600 ha; 33°07'N 005°03'W. Biological and Ecological Reserve, Permanent Hunting Reserve. A complex of three mountain wetlands at 1900-2100m that are fed by snowmelt and springs - they are among the most southernmost representatives of the lacustrine mountain ecosystems of the temperate paleo-arctic bioregion. The wetlands are important wintering sites for migratory birds such as the Ruddy Shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea) and the Crested Coot (Fulica cristata), as well as important sites for the maintenance of invertebrate endemism in the area. Other roles of the site, which is underlain by a karstique system, include its recharge of the groundwater table and provision of a drinking hole for local mammals such as the genet, jackal and Red fox. Activities around the area mainly include livestock raising, followed by tourism, rainbow trout aquaculture and sports fishing, especially in summer. The main threats are water extraction, overgrazing and organic pollution by animal and human use. Different NGOs have undertaken awareness programmes on the ecological, especially ornithological values of the site. Ramsar site no. 1468. Most recent RIS information: 2005. Archipel et dunes d'Essawira Site number: 1,469 | Country: Morocco | Administrative region: Essawira Area: 4,000 ha | Coordinates: 31°30'N 09°48'W | Designation dates: 15-01-2005 View Site details in RSIS Archipel et dunes d'Essawira. -

A New Species of Androctonus Ehrenberg, 1828 from Northwestern Egypt (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

A New Species of Androctonus Ehrenberg, 1828 from Northwestern Egypt (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, František Kovařík & Carlos Turiel November 2013 — No. 177 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Nouveau Découpage Régional Au Maroc.Pdf

01/03/13 Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc - collectivités au Maroc Rechercher dans ce site Accueil Actualités Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc Régions Chiffres Clès Documentations Régions Populations en 2008 Provinces et Préfectures Etudes Réglementations Effectif Part du Part de Nombre Liste Total Rural l’urbain Fonds de Soutien RendezVous Région 1 : TangerTétouan 2830101 41.72% 58.28% 7 Tanger‑Assilah Avis d'Appel d'Offres (Préfecture) Contact Us M'Diq ‑ Fnidq Affiliations (Préfecture) Chefchaouen (Province) Fahs‑Anjra (Province) Larache (Province) Tétouan (Province) Ouezzane (Province) Région 2 : Oriental et Rif 2434870 42,92% 57,08% 8 Oujda Angad (Préfecture) Al Hoceima (Province) Berkane (Province) Jrada (Province) Nador (Province) Taourirt (Province) Driouch (Province) Guercif (Province) Région 3 : Fès‑Meknès 4022128 43,51% 56,49% 9 Meknès (Préfecture) Fès (Préfecture) Boulemane (Province) El Hajeb (Province) Ifrane (Province) Sefrou (Province) Taounate (Province) Taza (Province) Moulay Yacoub (Province) Région 4 : Rabat‑Salé‑ 4272901 32,31% 67,69% 7 Rabat (Préfecture) Kénitra (Sale (Préfecture ﺗﺭﺟﻣﺔ Skhirate‑Temara (Préfecture) Template tips Learn more about working with Kenitra (Province) templates. Khemisset (Province) How to change this sidebar. Sidi Kacem (Province) Sidi Slimane (Province) https://sites.google.com/site/collectivitesaumaroc/nouveau-dcoupage-rgional 1/3 01/03/13 Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc - collectivités au Maroc Région 5 : Béni Mellal‑