4. Birch and Other (Dissolving) Metal Reductions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First General Electron Transfer Reductions of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives Using Samarium Diiodide

The First General Electron Transfer Reductions of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives Using Samarium Diiodide A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences 2014 Malcolm Peter Spain School of Chemistry Malcolm Spain PhD Thesis Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................... 5 Declaration................................................................................................................ 6 Copyright statement .................................................................................................. 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... 9 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 13 1.1 Introduction to samarium diiodide .................................................................. 13 1.2 Reduction of ketones and aldehydes ............................................................. 15 1.3 Reduction of carboxylic acid derivatives ....................................................... 23 Chapter 2. Investigations of the SmI2–H2O system ................................................. 27 2.0 Preliminary studies of the SmI2–H2O system ................................................ -

Reductions and Reducing Agents

REDUCTIONS AND REDUCING AGENTS 1 Reductions and Reducing Agents • Basic definition of reduction: Addition of hydrogen or removal of oxygen • Addition of electrons 9:45 AM 2 Reducible Functional Groups 9:45 AM 3 Categories of Common Reducing Agents 9:45 AM 4 Relative Reactivity of Nucleophiles at the Reducible Functional Groups In the absence of any secondary interactions, the carbonyl compounds exhibit the following order of reactivity at the carbonyl This order may however be reversed in the presence of unique secondary interactions inherent in the molecule; interactions that may 9:45 AM be activated by some property of the reacting partner 5 Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) Reduction of Amides to Amines 9:45 AM 6 Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) Reduction of Carboxylic Acids to Primary Alcohols O 3 R CO2H + BH3 R O B + 3 H 3 2 Acyloxyborane 9:45 AM 7 Common Reducing Agents (Sodium Borohydride) The reductions with NaBH4 are commonly carried out in EtOH (Serving as a protic solvent) Note that nucleophilic attack occurs from the least hindered face of the 8 carbonyl Common Reducing Agents (Lithium Borohydride) The reductions with LiBH4 are commonly carried out in THF or ether Note that nucleophilic attack occurs from the least hindered face of the 9:45 AM 9 carbonyl. Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) The Influence of Metal Cations on Reactivity As a result of the differences in reactivity between sodium borohydride and lithium borohydride, chemoselectivity of reduction can be achieved by a judicious choice of reducing agent. 9:45 AM 10 Common Reducing Agents (Sodium Cyanoborohydride) 9:45 AM 11 Common Reducing Agents (Reductive Amination with Sodium Cyanoborohydride) 9:45 AM 12 Lithium Aluminium Hydride Lithium aluminiumhydride reacts the same way as lithium borohydride. -

CHE202 Reductions and Heterocycles

CHE202 Structure & Reactivity in Organic Chemistry: ! Reduction Reactions and Heterocyclic Chemistry! 9 lectures, Semester B 2014! Dr. Chris Jones! ! [email protected]! Office: 1.07 Joseph Priestley Building! ! Office hours:! 9.30-10.30 am Tuesday! 1.30-2.30 pm Thursday (by appointment only)! Course structure and recommended texts! 2! §" Coursework:! !Semester B – week 9 ! !5% (‘Coursework 7’)! !Semester B – week 11! !5% (‘Coursework 8’)! ! §" Test:! !Semester B – week 12! !15% (‘Test 4’)! §" Recommended text books:! ‘Organic Chemistry’, Clayden, ‘Oxidation & Reduction in ‘Heterocyclic Chemistry’, Greeves & Warren, OUP, 2012.! Organic Chemistry’, Donohoe, Joule & Mills, Wiley, 2010.! OUP, 2000.! Don’t forget clickers! Overview of Reduction Chemistry lecture material! 3! §" Reduction:! - Definition (recap.)! - Reduction of carbon-carbon double and triple bonds! - Heterogeneous hydrogenation! - Homogeneous hydrogenation, including stereoselective hydrogenation! - Dissolved metal reductions! - Other methods of reduction! - Reduction of carbon-heteroatom double and triple bonds! - Reduction of carbonyl derivatives, addressing chemoselectivity! - Stereoselective reduction of carbonyl derivatives! - Reduction of imines and nitriles! - Reductive cleavage reactions! - Hydrogenolysis of benzyl and allyl groups! - Dissolved metal reduction! - Deoxygenation reactions! - Reduction of heteroatom functional groups! e.g. azides, nitro groups, N-O bond cleavage! Reduction: definition! 4! §" Reduction of an organic substrate can be defined as:! - The concerted -

Chemical Modification of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Via Alkali Metal Reduction

A 677 OULU 2016 A 677 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O. Box 8000 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATISUNIVERSITATIS OULUENSISOULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTAACTA SCIENTIAESCIENTIAEA A RERUMRERUM Elina Pulkkinen NATURALIUMNATURALIUM Elina Pulkkinen Professor Esa Hohtola CHEMICAL MODIFICATION University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen OF SINGLE-WALLED CARBON Postdoctoral research fellow Sanna Taskila NANOTUBES VIA ALKALI METAL REDUCTION Professor Olli Vuolteenaho University Lecturer Veli-Matti Ulvinen Director Sinikka Eskelinen Professor Jari Juga University Lecturer Anu Soikkeli Professor Olli Vuolteenaho UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF SCIENCE Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala ISBN 978-952-62-1243-2 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-1244-9 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3191 (Print) ISSN 1796-220X (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS A Scientiae Rerum Naturalium 677 ELINA PULKKINEN CHEMICAL MODIFICATION OF SINGLE-WALLED CARBON NANOTUBES VIA ALKALI METAL REDUCTION Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Technology and Natural Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in the Arina auditorium (TA105), Linnanmaa, on 15 June 2016, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2016 Copyright © 2016 Acta Univ. Oul. A 677, 2016 Supervised by Professor Marja Lajunen Doctor Janne Asikkala Reviewed by Professor Markku Leskelä Professor Mika Pettersson Opponent Professor Tuula Pakkanen ISBN 978-952-62-1243-2 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-1244-9 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3191 (Printed) ISSN 1796-220X (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2016 Pulkkinen, Elina, Chemical modification of single-walled carbon nanotubes via alkali metal reduction. University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Science Acta Univ. -

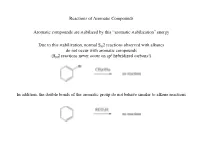

2 Reactions Observed with Alkanes Do Not Occur with Aromatic Compounds 2 (SN2 Reactions Never Occur on Sp Hybridized Carbons!)

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Aromatic compounds are stabilized by this “aromatic stabilization” energy Due to this stabilization, normal SN2 reactions observed with alkanes do not occur with aromatic compounds 2 (SN2 reactions never occur on sp hybridized carbons!) In addition, the double bonds of the aromatic group do not behave similar to alkene reactions Aromatic Substitution While aromatic compounds do not react through addition reactions seen earlier Br Br Br2 Br2 FeBr3 Br With an appropriate catalyst, benzene will react with bromine The product is a substitution, not an addition (the bromine has substituted for a hydrogen) The product is still aromatic Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Aromatic compounds react through a unique substitution type reaction Initially an electrophile reacts with the aromatic compound to generate an arenium ion (also called sigma complex) The arenium ion has lost aromatic stabilization (one of the carbons of the ring no longer has a conjugated p orbital) Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution In a second step, the arenium ion loses a proton to regenerate the aromatic stabilization The product is thus a substitution (the electrophile has substituted for a hydrogen) and is called an Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Energy Profile Transition states Transition states Intermediate Potential E energy H Starting material Products E Reaction Coordinate The rate-limiting step is therefore the formation of the arenium ion The properties of this arenium ion therefore control electrophilic aromatic substitutions (just like any reaction consider the stability of the intermediate formed in the rate limiting step) 1) The rate will be faster for anything that stabilizes the arenium ion 2) The regiochemistry will be controlled by the stability of the arenium ion The properties of the arenium ion will predict the outcome of electrophilic aromatic substitution chemistry Bromination To brominate an aromatic ring need to generate an electrophilic source of bromine In practice typically add a Lewis acid (e.g. -

Reductive Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes

Fullerenes, Nanotubes, and Carbon Nanostructures, 13: 375–382, 2005 Copyright # Taylor & Francis, Inc. ISSN 1536-383X print/1536-4046 online DOI: 10.1081/FST-200039375 Reductive Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes F. Borondics, M. Bokor, P. Matus, K. Tompa, and S. Pekker Research Institute for Solid State Physics and Optics, Budapest, Hungary E. Jakab Chemical Research Center, Budapest, Hungary Abstract: We present sidewall functionalization of carbon nanotubes via various dis- solving metal reduction methods. Carbanion complexes of lithium were prepared in liquid ammonia and THF and reacted with a series of alkyl and aryl halogenides, as well as methanol resulting in the formations of alkylated, arylated, and hydrogenated nanotube derivatives, respectively. The hydrogenation reactions were also performed on graphite. Thermal stabilities and chemical compositions were determined by thermogravimetry-mass spectrometry (TG-MS). Characteristic decomposition peaks, observed in the range of 350–6008C, suggest the formation of covalent derivatives upon functionalization. The compositions are 0.01–0.25 side group/carbon depending on the materials. NMR and Raman spectroscopic characterizations show the structural changes due to functionalization. Keywords: Functionalization of nanotubes, thermal stability, hydrogenation, alky- lation INTRODUCTION Functionalization of carbon nanotubes is an effective way to enhance the physical properties and improve the solubility, however, the aromatic character of nanotubes restricts the possible addition reactions. Various func- tionalization methods have been carried out such as fluorination (1, 2), oxidation (3), Birch reduction (4, 5), direct addition of reactive organic Address correspondence to F. Borondics, Research Institute for Solid State Physics and Optics, HAS, P.O. Box 49, Budapest H-1525, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 376 F. -

Fullerene-Acene Chemistry

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2007 Fullerene-acene chemistry: Part I Studies on the regioselective reduction of acenes and acene quinones; Part II Progress toward the synthesis of large acenes and their Diels-Alder chemistry with [60]fullerene Andreas John Athans University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Athans, Andreas John, "Fullerene-acene chemistry: Part I Studies on the regioselective reduction of acenes and acene quinones; Part II Progress toward the synthesis of large acenes and their Diels-Alder chemistry with [60]fullerene" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations. 363. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/363 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FULLERENE-ACENE CHEMISTRY: PART I: STUDIES ON THE REGIOSELECTIVE REDUCTION OF ACENES AND ACENE QUINONES; PART II: PROGRESS TOWARD THE SYNTHESIS OF LARGE ACENES AND THEIR DIELS- ALDER CHEMISTRY WITH [60]FULLERENE VOLUME 1 CHAPTERS 1-5 BY ANDREAS JOHN ATHANS B.S. University of New Hampshire, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy m Chemistry May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3 2 6 0 5 8 6 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Determination of the Effective Redox Potentials of Smi2, Smbr2, Smcl2

Article pubs.acs.org/joc ff Determination of the E ective Redox Potentials of SmI2, SmBr2, SmCl2, and their Complexes with Water by Reduction of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Reduction of Anthracene and Stilbene by Samarium(II) Iodide−Water Complex Michal Szostak,* Malcolm Spain, and David J. Procter* School of Chemistry, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, United Kingdom *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Samarium(II) iodide−water complexes are ideally suited to mediate challenging electron transfer reactions, yet the effective redox potential of these powerful reductants has not been determined. Herein, we report an examination of the − reactivity of SmI2(H2O)n with a series of unsaturated hydrocarbons and alkyl halides with reduction potentials ranging from 1.6 − − to 3.4 V vs SCE. We found that SmI2(H2O)n reacts with substrates that have reduction potentials more positive than 2.21 V vs SCE, which is much higher than the thermodynamic redox potential of SmI2(H2O)n determined by electrochemical methods − ff (up to 1.3 V vs SCE). Determination of the e ective redox potential demonstrates that coordination of water to SmI2 increases ff the e ective reducing power of Sm(II) by more than 0.4 V. We demonstrate that complexes of SmI2(H2O)n arising from the addition of large amounts of H2O (500 equiv) are much less reactive toward reduction of aromatic hydrocarbons than complexes of SmI2(H2O)n prepared using 50 equiv of H2O. We also report that SmI2(H2O)n cleanly mediates Birch reductions of substrates bearing at least two aromatic rings in excellent yields, at room temperature, under very mild reaction conditions, and with selectivity that is not attainable by other single electron transfer reductants. -

Kinetics of the Birch Reduction

1808 A. Greenfield and U. Schindewolf: Kinetics of the Birch Reduction Kinetics of the Birch Reduction A. Greenfield and U. Schindewolf Universita¨t Karlsruhe, Institut fu¨r physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie, Kaiserstraße 12, D-76131 Karlsruhe, Germany Key Words: Chemical Kinetics / Liquid Ammonia / Metal Ammonia Solutions / Solutions Because of contradictions in the literature, we reinvestigated the kinetics of the Birch reduction, i.e. the hydro- genation of benzene and its derivatives in metal ammonia solutions (MAS; containing solvated electrons e– and metal cations M+) with alcohols to yield the corresponding cyclohexa-1,4-dien compounds (e.g. 2Li+ 2CH OH+C H 2CH OLi+C H ). The kinetics of this reaction are obscured since the hydrogen reaction 3 6 6) 3 6 8 proceeds parallel to it (2Li+2CH3OH 2CH3OLi+H2). The two reactions differ in their activation energies (6.5 and 22.5 kJ/Mol resp.); and in the) series of the alkali metals Li, Na and K the rate of the Birch reduction decreases, whereas that of the hydrogen reaction increases. However, in the metal concentration range around 0.01 M, both reactions have within the experimental error the same reaction order with respect to the metal (&0.8). Both are accelerated by addition of alkali cations common to the dissolved alkali metal, and both are decelerated by addition of alkali cation complexing cryptands. Thus we conclude that the cations are involved in the kinetics of both reactions, probably by forming intermediate ion pairs or shifting pre-equilibria in which solvated electrons are involved. The experimental data of both reactions can be described very well 2 – + 2 – + with the rate laws v(B)=kB f [e ][Li ][CH3OH][C6H6] and v(H)=kH f [e ][Li ][CH3OH] resp. -

Birch Reduction of Benzenesulfonamide, N,N- Dimethylbenzenesulfonamide, N,N-Diisobutylbenzenesulfonamide, and 2-Mesitylenesulfonamide

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1972 Birch reduction of benzenesulfonamide, N,N- dimethylbenzenesulfonamide, N,N-diisobutylbenzenesulfonamide, and 2-mesitylenesulfonamide Vishnubhai V. Patel University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Patel, Vishnubhai V.. (1972). Birch reduction of benzenesulfonamide, N,N-dimethylbenzenesulfonamide, N,N-diisobutylbenzenesulfonamide, and 2-mesitylenesulfonamide. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/420 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIRCH REDUCTION OF BENZENESULFONAMIDE, N,N-DIMETHYLBENZENESULFONAMIDE, N,N-DIISOBUTYLBENZENESULFONAMIDE AND 2-MESITYIENESULFONAMIDE. A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School -1 University of the Pacific I I -i In Partial Fulfillrnent of _j the Requirement for the Degree Master of Science by Vishnubhai V. Patel June 1972 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Charles A. Matuszak for his unceasing encouragement and help during the course of-this research. My grateful thanks to Dr. Herschel G. Frye and Dr. Donald K. Wedegaertner for their kind suggestions. I would like to thank Dr. E.G. Cobb, Chainnan of the Chemistry Department, for his help and facilities. Finally, rey sincere appreciation to Mrs. Dawn Mallard for an excellent job of typing. --j j TABLE OF CONTENTS ,PAGE INTRODUC'J1ION . -

Carbon Nanotubes Covalent Hybrid As a Metal-Free Electrocatalyst

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Two-electron oxygen reduction on fullerene C60-carbon nanotubes covalent hybrid as a metal-free Received: 6 June 2019 Accepted: 2 September 2019 electrocatalyst Published: xx xx xxxx Aliyeh Hasanzadeh1, Alireza Khataee1,2, Mahmoud Zarei3 & Yifeng Zhang 4 Nanocarbon materials are considered to be active for electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) synthesis. In the present work, a new type of fullerene 60 (C60)-carbon nanotubes (CNTs) hybrid with covalently attached C60 onto outer surface of CNTs was synthesized. The structure of C60-CNT hybrid was confrmed by physical and chemical characterizations and its conformation is proposed featuring the covalent incorporation of CNTs and C60 derivative. C60- CNT hybrid showed high efciencies on electro-generating H2O2, owing to huge surface area and −1 intermolecular electron-transfer in the hybrid structure. A high H2O2 production rate of 4834.57 mg L h−1 (426.58 mmol L−1) was achieved at − 0.2 V vs saturated calomel electrode (SCE). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is an eco-friendly and essential chemical that is widely used as an oxidizer, antiseptic 1 and bleaching agent for a huge range of industrial processes . Te well-developed anthraquinone-based H2O2 production is the current method that has taken in multistep reactions and separations, energy-intensive and along with the production of organic wastes2,3. Furthermore, the use of noble‐metal based catalysts (Pt, Pd, Au, 4 and Ag) and hydrogenation step under high-pressure H2 have a negative efect on the production costs . Tese major disadvantages have triggered the interests in the development of more facile and green method for H2O2 generation. -

Chemical Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes for Controlled Optical, Electrical and Dispersion Properties

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CHEMICAL FUNCTIONALIZATION OF CARBON NANOTUBES FOR CONTROLLED OPTICAL, ELECTRICAL AND DISPERSION PROPERTIES Alexandra Brozena, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor YuHuang Wang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry A carbon nanotube is a graphitic sheet, rolled into a one-dimensional, hollow tube. This structure provides certain individual nanotubes with high conductivity and near-infrared optical activity. These properties are not necessarily translated at the macroscale, however, due to strong van der Waals attractive forces that determine the behavior at the bulk level – exemplified by aggregation of nanotubes into bundles with significantly attenuated functionality. Different methods of carbon nanotube covalent functionalization are studied to improve dispersion while simultaneously maintaining intrinsic electrical and optical properties. In addition to retention of known behavior, new carbon nanotube photoluminescence pathways are also revealed as a result of this same covalent functionalization strategy. With various wet chemistries, including super-acid oxidation, the Billups- Birch reaction, and various diazonium based reactions, that utilize strong reducing or oxidizing conditions to spontaneously exfoliate aggregated carbon nanotubes, we are able to covalently functionalize individually dispersed nanotubes in a highly scalable manner. Covalent addition to the nanotube sidewalls converts the native sp 2 hybridized carbon atoms to sp 3 hybridization, which helps disrupt inter-tube van der Waals forces. However, this change in hybridization also perturbs the carbon nanotube electronic structure, resulting in an undesired loss of electrical conductivity and optical activity. We observe that controlling the location of functionalization, such as to the outer-walls of double-walled carbon nanotubes or as discrete functional “bands,” we avert the loss of desirable properties by leaving significant tracts of sp 2 carbon atoms unperturbed.