Miriam Helga Auer Poetry in Motion and Emotion –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

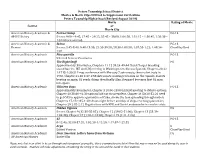

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Introduction

Introduction BY ROBERT WELTSCH Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/leobaeck/article/8/1/IX/938684 by guest on 27 September 2021 No greater discrepancy can be imagined than that between the three men with whom we begin the present volume of the Year Book. It is almost a reflection of what, since Sir Charles Snow's famous lecture, has become the current formula of "The Two Cultures". Ismar Elbogen devoted his whole life to Jewish scholarship, he was a true representative of the humanities. Fritz Haber on the other hand was a great scientist, though his biographer, doctor and friend, is eager to point out that at his time the two cultures were not yet so far apart, and that Haber was devoted to poets like Goethe and himself made verses. But what about our third man? For his sake, we may be tempted to add to the array a "Third Culture", the world of Mammon, seen not from the aspect of greed, but, in this special case, to be linked in a unique way with active work for the good of fellow-men — in philanthropy of a magnitude which has very few parallels in the history of all nations. There is little that we could add, in the way of introduction, to the story of Baron Hirsch as told by Mr. Adler-Rudel. Among the Jewish public it is not always remembered that the man was a German Jew, a descendant of a Bavarian family of court bankers who acquired the castle of Gereuth. Owing to the early transfer of his residence to Brussels and later to Paris, and perhaps also due to his collaboration with the Alliance Israelite Universelle, Hirsch is in the mind of the uninformed public often associated with French Jewry. -

Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in the Simpsons

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD Film Studies in the University of Hull by Jemma Diane Gilboy, BFA, BA (Hons) (University of Regina), MScRes (University of Edinburgh) April 2016 Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons by Jemma D. Gilboy University of Hull 201108684 Abstract (Thesis Summary) The objective of this thesis is to establish meme theory as an analytical paradigm within the fields of screen and fan studies. Meme theory is an emerging framework founded upon the broad concept of a “meme”, a unit of culture that, if successful, proliferates among a given group of people. Created as a cultural analogue to genetics, memetics has developed into a cultural theory and, as the concept of memes is increasingly applied to online behaviours and activities, its relevance to the area of media studies materialises. The landscapes of media production and spectatorship are in constant fluctuation in response to rapid technological progress. The internet provides global citizens with unprecedented access to media texts (and their producers), information, and other individuals and collectives who share similar knowledge and interests. The unprecedented speed with (and extent to) which information and media content spread among individuals and communities warrants the consideration of a modern analytical paradigm that can accommodate and keep up with developments. Meme theory fills this gap as it is compatible with existing frameworks and offers researchers a new perspective on the factors driving the popularity and spread (or lack of popular engagement with) a given media text and its audience. -

Dead Poets Society: Final Script

Dead Poets Society: Final Script original screenplay by Tom Schulman, film directed by Peter Weir This is the final script of the theatrical release of Dead Poets Society. It was obtained from Simply Scripts and initially contained only the dialog from the film. (No descriptions, actions, locations, anything...) I went through the script and added in descriptive text. As I have not had a chance to double check everything, I am sure there are a few errors, typos, or bits of incorrect dialog still. I'll try to verify it all shortly. INT. WELTON ACADEMY HALLWAY - DAY A young boy, dressed in a school uniform and cap, fidgets as his mother adjusts his tie. MOTHER Now remember, keep your shoulders back. A student opens up a case and removes a set of bagpipes. The young boy and his brother line up for a photograph PHOTOGRAPHER Okay, put your arm around your brother. That's it. And breathe in. The young boy blinks as the flash goes off. PHOTOGRAPHR Okay, one more. An old man lights a single candle. A teacher goes over the old man's duties. TEACHER Now just to review, you're going to follow along the procession until you get to the headmaster. At that point he will indicate to you to light the candles of the boys. MAN All right boys, let's settle down. The various boys, including NEIL, KNOX, and CAMERON, line up holding banners. Ahead of them is the old man, followed by the boy with the bagpipes with the two youngest boys at the front. -

The Drama of German Expressionism He National Theatre Recently Staged a Pile of the Bank’S Money; His Wife and the Fate of the Main Character

VOLUME 14 NO.3 MARCH 2014 journal The Association of Jewish Refugees The drama of German Expressionism he National Theatre recently staged a pile of the bank’s money; his Wife and the fate of the main character. an important, but rarely seen, play Daughters, representing the conventional The play’s language is stripped down to its by the best-known of the German family life that he abandons; and the various basics for maximum expressive effect, in line TExpressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser figures that he subsequently encounters in with the Expressionists’ desire to rediscover (1878-1945). From Morning to Midnight his whirlwind, one-day trajectory through the essential humanity of mankind beneath (Von morgens bis mitternachts) was written the deadening layers of modern life. This in 1912 and first performed in April 1917 striking, declamatory style was known at the Munich Kammerspiele. It is a classic as the ‘Telegrammstil’, attributed first to piece of Expressionist theatre, with its the poet August Stramm: ‘Mensch, werde clipped, staccato dialogue, its abandonment wesentlich!’ (‘Man, become essential!’) was of a conventionally structured plot and the final line of the poem ‘Der Spruch’ realistic, individualised characters, and (‘The Saying’) by the Expressionist poet its attempt to pierce through the surface Ernst Stadler. The characteristic mode of detail of everyday bourgeois life to convey expression for these writers was a rhetorical the deeper reality of human existence in an outcry of extreme intensity, which became industrialised, mechanised society devoid of known as ‘der Schrei’ (‘the scream’), with values beyond soulless materialism. obvious reference to the celebrated painting Although this play was performed at by Edvard Munch. -

Synopsis Drum Taps

Drum-Taps Synopsis “Drum-Taps” is a sequence of 43 poems about the Civil War, and stands as the finest war poetry written by an American. In these poems Whitman presents, often in innovative ways, his emotional experience of the Civil War. The sequence as a whole traces Whitman's varying responses, from initial excitement (and doubt), to direct observation, to a deep compassionate involvement with the casualties of the armed conflict. The mood of the poems varies dramatically, from excitement to woe, from distant observation to engagement, from belief to resignation. Written ten years after "Song of Myself," these poems are more concerned with history than the self, more aware of the precariousness of America's present and future than of its expansive promise. In “Drum-Taps” Whitman projects himself as a mature poet, directly touched by human suffering, in clear distinction to the ecstatic, naive, electric voice which marked the original edition of Leaves of Grass . First published as a separate book of 53 poems in 1865, the second edition of Drum-Taps included eighteen more poems ( Sequel to Drum-Taps ). Later the book was folded into Leaves of Grass as the sequence “Drum-Taps,” though many individual poems were rearranged and placed in other sections. By the final version (1881), "Drum-Taps" contained only 43 poems, all but five from Drum-Taps and Sequel . Readers looking for a reliable guide to the diverse issues raised in the sequence would be advised to turn to the fine study by Betsy Erkkila. Interested readers will find the more ironic and contemplative poems of Herman Melville's Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) a remarkable counterpoint to Whitman's poems. -

Diamonds for Tears Chords

Diamonds for tears chords click here to download Chords for Poets of the fall - Diamonds for tears (Unplugged). Play along with guitar, ukulele, or piano with interactive chords and diagrams. Includes transpose . Choose and determine which version of Diamonds For Tears chords and tabs by Poets Of The Fall you can play. Last updated on Diamonds for Tears - Poets of the Fall - free sheet music and tabs for cello, distortion guitar, fifths sawtooth wave, overdrive guitar, orchestral harp, saw wave . Learn & play tab for rhythm guitars, bass, percussion, vocal and others with free online tab player, speed control and loop. Download original. Even beginners can play Diamonds For Tears by Poets Of The Fall like a pro! It's very easy: take your guitar and watch tablature & chords in our online player. Diamonds for Tears chords by Poets Of The Fall. Play song with guitar, piano, bass, ukulele. Chords list: C#, F#, C#m, F#m, A, G#m, B, E - Yalp. Get chords for songs by Diamond Tears. Diamonds For Tears by Poets Of The Fall tab with free online tab player. One accurate version. Recommended by The Wall Street Journal. Fm A#m C# G#m B F# D#m E G# D#] Chords for Racoon - Tears For Diamonds with capo tuner, play along with guitar, piano & ukulele. Diamonds And Tears Chords by Suzy Bogguss Learn to play guitar by chord and tabs and use our crd diagrams, transpose the key and more. Her Diamonds Chords by Rob Thomas Learn to play guitar by chord and tabs Am Her tears like diamonds on the floor C And her diamonds bring me down G. -

Chernobyl Template.Qxd 16/09/2019 11:08 Page 39

9Chernobyl_Template.qxd 16/09/2019 11:08 Page 39 39 Chernobyl On 3 February 1987, during a lecture trip to Japan, I was invited to meet five members of the Japan Atomic Industrial Forum Inc. Zhores Medvedev They wanted to discuss my book, Nuclear Disaster in the Urals, which described the consequences of the Kyshtym disaster, an On 8 August 2019, a explosion at a nuclear waste site in the deadly nuclear explosion Soviet Union in 1957. took place in northern The book, published in New York in 1979 Russia in the vicinity of and translated into Japanese in 1982, was the Nenoksa weapons then still the only published description of testing range. At least five this accident. The Kyshtym disaster was not people are said to have yet included in a list of nuclear accidents died. Subsequently, a prepared by the International Atomic Russian state weather Energy Agency (IAEA). Top of this list, agency confirmed release recorded at a topofthescale 7 in severity, into the atmosphere of was Chernobyl, Three Mile Island was strontium, barium and scale 5, and the fire at Windscale in other radioactive isotopes, England, in 1957, was scale 3. (The indicating that a nuclear International Nuclear Event Scale was reactor was involved in revised several times, subsequently, and the the explosion. fire at Windscale is now reckoned to be Zhores Medvedev died scale 5.) in 2018, before this recent In 1987, I had already started to study the explosion. Back in 2011, available information on Chernobyl he charted a trail of because I was not satisfied with the Soviet nuclear disasters from Report to the IAEA, which blamed mainly Kyshtym in the the power station personnel for gross Cheliabinsk region of operational errors. -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

MES-Päätökset AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO

MES-päätökset 1/56 AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO Alajärvi Miina Lappi-räppiä käsittelevän pitkän dokumenttielokuvan “Lappi Itsenäiseksi Mixtape” 1 000,00 € (työnimi) kehittely ja käsikirjoit Anundi Anna Annabella Anundi - OLD TIMES 200,00 € Boogieman Management Oy Temple Balls 'Thunder from the North' 800,00 € Finn Andersson Film Productions Oy Fan Theories - Love Is What Is Left 300,00 € Finnish Metal Events Oy Tuska Utopia -virtuaalikonserttisarjan jatkaminen 1 500,00 € Folk Extreme Oy Suistamon Sähkö -yhtyeen musiikkivideo 'Up'n Down' 500,00 € Suistamon Sähkö -yhtyeen musiikkivideo 'Kutsu' 1 500,00 € Ginger Vine Management Oceanhoarsen One with the Gun -musiikkivideo 200,00 € Heinonen Ilkka Ilkka Heinonen Trion musiikkivideo 'Narrien kruunajaiset' 300,00 € Hermansson Jani Hellä Hermanni -artistin musiikkivideo 'Olivetti Lettera' 400,00 € Ikurin Turpiini oy Pate Mustajärvi - Älkää jättäkö -musiikkivideo 750,00 € Pate Mustajärvi:Elvis - musiikkivideo 500,00 € Pate Mustajärvi: Jos maailma on pystyssä huomenna 500,00 € Insomniac Oy Poets of the Fall -yhtyeen musiikkivideo Stay Forever 350,00 € Intervisio Oy Maalaispoika 1 000,00 € 15.06.2021 MES-päätökset 2/56 AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO Joensuun Popmuusikot ry Rokumentti Rock Film Festival 2021 1 000,00 € Kaiku Entertainment Oy Elastinen - Ollu tääl 500,00 € Ares - Matkoil 300,00 € Kameron Oy Moon Shot - Confessions 2 000,00 € KHY Suomen Musiikki Oy Villa - Pisarat 750,00 € Kilpi Topi Pelimannin penkillä 2 (työnimi) 1 500,00 € Kiviniemi Joel Rosa Costa - Musta 750,00 € Klippel Mirja Mirja Klippelin -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson,