Download Films in Our Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sep - Dec 2017 Breweryarts.Co.Uk | 01539 725133 | @Lakescinema

Cinema Sep - Dec 2017 breweryarts.co.uk | 01539 725133 | @lakescinema The Killing of a Sacred Deer | 8-11 Dec 01 The Brewery Cinema | September - December 2017 Cinema specials SEASON TICKETS In this Corner of the World | 14 Oct See 3 Films Save 15% See 5 Films Save 25% USEFUL INFO Tickets must be purchased at the same time. T&Cs apply. Selected films only. Doors open 15 minutes prior to start time, which includes adverts & trailers All our cinema screenings have allocated seating, THE REEL DEAL choose your preferred view when booking Enjoy a Movie & a Pizza You are welcome to enjoy alcoholic drinks in our for only £15 | Sun-Thu | 5-8pm cinema screens - served in plastic glasses only Only food & drink purchased at the Brewery may be taken into the cinemas. All profits from the food Student TICKETS & drink concessions help fund our arts programme. Please note hot drinks are not permitted in Screen 3 Any film anytime only £7.50 Screens 1 & 2 are equipped with an infra-red assistive listening system FAMILY TICKETs Tickets are available online www.breweryarts.co.uk/ Admit 4 for just £28 cinema and from our box office 01539 725133 Box office is open Noon - 8.30pm daily (programme dependent) MATINEE MOVIES Ticket Prices: All films listed in this brochure with confirmed times and dates £7.50 Silver Screenings only £7.50 (unless otherwise stated) See website for special offers, information and T&Cs. Visit our website for more fantastic All our venues are available for private hire; contact offers and terms and conditions. -

Presents a Film by TRACEY DEER 92 Mins, Canada, 2020 Language: English with Some French

Presents a film by TRACEY DEER 92 mins, Canada, 2020 Language: English with some French Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 217 – 136 Geary Ave Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com BEANS Festivals, Achievements and Awards Awards & Achievements DGC Discovery Award – 2020 WGC Screenwriting Award, Feature Film – 2021 Canadian Screen Awards – 2021 Best Motion Picture, Winner John Dunning Best First Feature Film Award, Winner Achievement in Casting, Nomination Achievement in Sound Mixing, Nomination Achievement in Cinematography, Nomination Vancouver Films Critics Circle – 2021 One to Watch: Kiawentiio Best Supporting Actress: Rainbow Dickerson Festivals Berlinale, Generation Kplus, Germany – 2021 Crystal Bear for Best Film Toronto International Film Festival, Canada – 2020 TIFF Emerging Talent Award: Tracey Deer TIFF Rising Stars: Rainbow Dickerson TIFF’s Canada’s Top Ten Vancouver International Film Festival, Canada – 2020 Best Canadian Film Yukon Available Light Film Festival, Canada – 2021 Made in the North Award for Best Canadian Feature Film Audience Choice Best Canadian Feature Fiction Kingston Canadian Film Festival, Canada – 2021 Limestone Financial People’s Choice Award Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival, USA – 2021 Audience Choice Award: Nextwave Global Features Provincetown Film Festival - 2021 NY Women in Film & Television Award for Excellence -

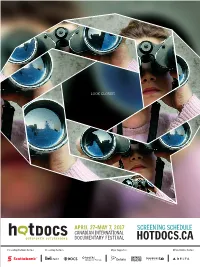

Hotdocs.Ca Hotdocs.Ca

LOOK CLOSER IMAGE: THE GIRL DOWN LOCH ÄNZI CONCEPT: CAI SEPULIS DESIGN: franklin HEAVY APRIL 27–MAY 7, 2017 HOTDOCS.CA Presenting Platinum Partner Presenting Partners Major Supporters Official Airline Partner Your dream in focus. Honours Bachelor of Film and Television APRIL 27–MAY 7, 2017 : HOT DOCS CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL WELCOME TO HOT DOCS 2017 PHOTO: CHRISTIAN PEÑA FIND YOUR FILMS CHOOSE YOUR TICKETS OR PASS Browse films by program or use the title index to find films. More detailed SINGLE TICKETS: $17 film descriptions and a subject index are available at www.hotdocs.ca. SPECIAL EVents: $22–24 BUY YOUR TICKETS $60–150 Food & Film Events ADVANCE Tickets Ticket Packages Perfect for sharing with your friends and family, you can use as many WWW.HOTDOCS.CA tickets as you like per screening and can redeem them in advance. 416.637.5150 Tickets not valid for special events. C raveTV Hot Docs Box Office UNDER 30/SENIOR 6-PACK: $99 605 Bloor Street West 10-PACK: $149 Hours 20-PACK: $249 Monday–Friday: 10am–7pm Saturday–Sunday: 10am–5pm Ticket package holders can redeem their tickets online at www.hotdocs.ca, Thursday, April 27–Sunday, May 7: 10am–7pm by phone or in person at the CraveTV Hot Docs Box Office. SAME DAY Tickets Passes Same day tickets are available online, by phone and at the CraveTV Hot Docs Access screenings without having to select films or book tickets Box Office until one hour before screening time. in advance. Simply show your pass at the screening venue to obtain Additionally, each venue opens its box office one hour before its first your ticket. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Deepa Mehta (See More on Page 53)

table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Experimental Cinema: Welcome to the Festival 3 Celluloid 166 The Film Society 14 Pixels 167 Meet the Programmers 44 Beyond the Frame 167 Membership 19 Annual Fund 21 Letters 23 Short Films Ticket and Box Offce Info 26 Childish Shorts 165 Sponsors 29 Shorts Programs 168 Community Partners 32 Music Videos 175 Consulate and Community Support 32 Shorts Before Features 177 MSPFilm Education Credits About 34 Staff 179 Youth Events 35 Advisory Groups and Volunteers 180 Youth Juries 36 Acknowledgements 181 Panel Discussions 38 Film Society Members 182 Off-Screen Indexes Galas, Parties & Events 40 Schedule Grid 5 Ticket Stub Deals 43 Title Index 186 Origin Index 188 Special Programs Voices Index 190 Spotlight on the World: inFLUX 47 Shorts Index 193 Women and Film 49 Venue Maps 194 LGBTQ Currents 51 Tribute 53 Emerging Filmmaker Competition 55 Documentary Competition 57 Minnesota Made Competition 61 Shorts Competition 59 facebook.com/mspflmsociety Film Programs Special Presentations 63 @mspflmsociety Asian Frontiers 72 #MSPIFF Cine Latino 80 Images of Africa 88 Midnight Sun 92 youtube.com/mspflmfestival Documentaries 98 World Cinema 126 New American Visions 152 Dark Out 156 Childish Films 160 2 welcome FILM SOCIETY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Dear Festival-goers… This year, the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival celebrates its 35th anniversary, making it one of the longest-running festivals in the country. On this occasion, we are particularly proud to be able to say that because of your growing interest and support, our Festival, one of this community’s most anticipated annual events and outstanding treasures, continues to gain momentum, develop, expand and thrive… Over 35 years, while retaining a unique flavor and core mission to bring you the best in international independent cinema, our Festival has evolved from a Eurocentric to a global perspective, presenting an ever-broadening spectrum of new and notable film that would not otherwise be seen in the region. -

1962-63 Year Book Canadian Motion Picture Industry

FROM THE OF THE CREATIVE the industry’s most distinguished array of moviemaking talents will make this Columbia’s brilliant year of achievement. COLUMBIA PICTURES C0RP0RATI0 The world’s most popular fountain drinks! ORANGE People get thirsty just looking at it! The New Queen Dispenser is illuminated and animated to attract customers and earn profits—it does ! and Easse ROOT BEER This self-contained Hires Barrel will increase sales by 300% or more . and it’s all plus business! PRODUCTS OF CRUSH INTERNATIONAL LIMITED MONTREAL • TORONTO • WINNIPEG • VANCOUVER 1962-63 YEAR BOOK CANADIAN MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY WITH TELEVISION SECTION PRICE $3.00 FILM PUBLICATIONS of Canada, Ltd. 175 BLOOR ST. EAST TORONTO 5. ONT. CANADA Editor: HYE BOSSIN Assistants: Miss E. Silver and Ben Halter this is where the show goes on The sound and projection equipment in your booth is the heart of your theatre. If this equipment fails, your show stops. The only protection against this is top quality equipment, regularly serviced. That's why it pays to talk to the people at General Sound. They have the most complete line of High Fidelity and Stereo sound and projection equipment in Canada. You have a whole range of fine names to choose from, backed up by first rate service facilities from coast- to-coast. Call General Sound, the heart of good picture projection, tomorrow. General Sound m, GENERAL SOUND AND THEATRE EQUIPMENT LTD. S 861 BAY STREET, TORONTO Offices in Voncouver, Winnipeg, Calgary, Montreal, Halifax, Saint John Index of Sections Pioneer of the Year Award 16 Exhibition ..... ----- 19 Theatre Director 37 Distribution ________ 63 Production . -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada's Feature Film Policy Since

Media Industries 4.2 (2017) DOI: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.204 Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada’s Feature Film Policy since 20001 Charles Tepperman2 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY c.tepperman [AT] ucalgary.ca Abstract: This essay provides a case study of one nation’s efforts to defend its culture from the influx of Hollywood films through largely bureaucratic means and focused on the increasingly outdated metric of domestic box-office performance. Throughout the early 2000s, Canadian films accounted for only around 1 percent of Canada’s English-language market, and were seen by policy makers as a perpetual “problem” that needed to be fixed. Similar to challenges found in most film-producing countries, these issues were navigated very differently in Canada. This period saw the introduction of a new market-based but cultural “defense” oriented approach to Canadian film policy. Keywords: Film Policy, Production, Canada Introduction For over a century, nearly every film-producing nation has faced the challenge of competing with Hollywood for a share of its domestic box office. How to respond to the overwhelming flood of expensively produced and slickly marketed films that capture most of a nation’s eye- balls? One need not be a cultural elitist or anti-American to point out that the significant presence of Hollywood films (in most countries more than 80 percent) can severely restrict the range of films available and create barriers to the creation and dissemination of home- grown content.3 Diana Crane notes that even as individual nations employ cultural policies to develop their film industries, these efforts “do not provide the means for resisting American domination of the global film market.”4 In countries like Canada, where the government plays a significant role in supporting the domestic film industry, these challenges have political and Media Industries 4.2 (2017) policy implications. -

Kingcanfilmfest.Com FEB 26 to MAR 1

presented by FEB 26 to MAR1 2O15 kingcanfilmfest kingcanfilmfest.com TiVo Service¹ lets you record up to 6 shows at once, access Netflix² and watch your recordings on the go. Get it only from Cogeco. 1-877-449-4474 • Cogeco.ca/TiVo How can we help you? TABLE OF CONTENTS Sponsors 2 tickets and Venues 5 Schedule 6 festival greetings 8 FILMS SHORT FILM PROGRAMS Big neWS from grand roCk 10 Canadian ShortS Program 24 after the BaLL 11 LoCaL ShortS Program 25 aLL the time in the WorLd 11 Youth ShortS Program 25 BerkShire CountY 12 C iS for Canada 26 dirtY SingLeS 13 muSiC Video ShortS Program 26 the father of hoCkeY 13 fauLt 14 feLix and meira 14 Workshops 28 in her PLaCe 15 music 30 La Petite reine 15 receptions 31 LuCk’S hard 17 maPS to the StarS 17 mommY 18 monSoon 18 PorCh StorieS 19 the PriCe We PaY 19 retroSPeCtiVe: manY kingStonS 20 SoL 21 the StronghoLd 21 tu dorS niCoLe 22 VioLent 22 PRESENTING SPONSORS PRIMETIME/PROGRAM SPONSORS SUPPORTERS FEATURE FILM SPONSORS 2 MEDIA SPONSORS the Queen’s University FILM SPONSORS FESTIVAL FRIENDS HOSPITALITY FRIENDS MEDIA FRIENDS Le Centre culturel Frontenac Amadeus Fusix Kamik AquaTerra by Clark Kingstonist Kingston Community Olivea Point of View Magazine Credit Union Pan Chancho Queen’s TV Petrie Ford Tango Nuevo Rogers K-Rock Centre SGPS Tir Nan Og Snapd Staples Station 14 Wellington Foreign Exchange FESTIVAL PARTNERS Film Circuit (TIFF), George Taylor Richardson Memorial Fund, National Film Board of Canada, Original Hockey Hall of Fame, Queen’s University AMS, Ubisoft, The Screening Room COMMUNITY SPONSORS Brew Pub, Brian’s Record Option, Campus One Stop, Card’s Bakery, Classic Video, David’s Tea, Five Guys Burger and Fries, Genene Maurice RMT, LSP Designs, Novel Idea, Pasta Genova, The Pita Pit, QFLIC, Rankin Productions, Secret Garden Inn, Sima Sushi, Ta-Ke Sushi, Tommy’s, The Works 3 For 15 years KCFF has been dedicated to exhibiting Canadian ƓOPDQGLVGHHSO\FRPPLWWHGWR ensuring its continued development & growth. -

Mckinney Macartney Management Ltd

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd AMY ROBERTS - Costume Designer THE CROWN 3 Director: Ben Caron Producers: Michael Casey, Andrew Eaton, Martin Harrison Starring: Olivia Colman, Tobias Menzies and Helena Bonham Carter Left Bank Pictures / Netflix CLEAN BREAK Director: Lewis Arnold. Producer: Karen Lewis. Starring: Adam Fergus and Kelly Thornton. Sister Pictures. BABS Director: Dominic Leclerc. Producer: Jules Hussey. Starring: Jaime Winstone and Samantha Spiro. Red Planet Pictures / BBC. TENNISON Director: David Caffrey. Producer: Ronda Smith. Starring: Stefanie Martini, Sam Reid and Blake Harrison. Noho Film and Television / La Plante Global. SWALLOWS & AMAZONS Director: Philippa Lowthorpe. Producer: Nick Barton. Starring: Rafe Spall, Kelly Macdonald, Harry Enfield, Jessica Hynes and Andrew Scott. BBC Films. AN INSPECTOR CALLS Director: Aisling Walsh. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: David Thewlis, Miranda Richardson and Sophie Rundle. BBC / Drama Republic. PARTNERS IN CRIME Director: Ed Hall. Producer: Georgina Lowe. Starring: Jessica Raine, David Walliams, Matthew Steer and Paul Brennen. Endor Productions / Acorn Productions. Gable House, 18 –24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 AMY ROBERTS Contd … 2 CILLA Director: Paul Whittington. Producer: Kwadjo Dajan. Starring: Sheridan Smith, Aneurin Barnard, Ed Stoppard and Melanie Hill. ITV. RTS CRAFT & DESIGN AWARD 2015 – BEST COSTUME DESIGN BAFTA Nomination 2015 – Best Costume Design JAMAICA INN Director: Philippa Lowthorpe Producer: David M. Thompson and Dan Winch. Starring: Jessica Brown Findlay, Shirley Henderson and Matthew McNulty. Origin Pictures. THE TUNNEL Director: Dominik Moll. Producer: Ruth Kenley-Letts. Starring: Stephen Dillane and Clemence Poesy. Kudos. CALL THE MIDWIFE (Series 2) Director: Philippa Lowthorpe.