Consumer Preference and Willingness to Pay for Tomato Juice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low FODMAP Diet

The Low FODMAP Diet FOOD GROUP FOODS TO AVOID FOODS TO TRY INSTEAD Grains Foods made from wheat or wheat Rice, corn tortilla chips, gluten-free flour including: bread, cereal grains (like buckwheat and quinoa), and pasta foods made with gluten-free flour Fruits Apples, avocado, ripe bananas, Unripe bananas, most types of watermelon, grapefruit, pears, berries, grapes, cantaloupe, oranges, peaches, plums, most canned or pineapple, kiwi, rhubarb dried fruits Vegetables Garlic, onion, asparagus, beets, Bell peppers, cucumbers, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, black beans, lettuce, potatoes, tomatoes, kidney beans, peas corn, celery, green beans Meats & Proteins Most processed meats, meat served Beef, chicken, canned tuna, eggs, in fruit sauces, chorizo, sausage, most fish, lamb, pork, turkey, pistachios, cashews sunflower seeds, peanuts Dairy Milk (from cow, sheep or goat), Dairy-free milk, hard cheeses, half buttermilk, sour cream, yogurt, and half, mozzarella, sherbet, small some soft cheeses, ice cream, amounts of cream cheese sweetened condensed milk Non-Dairy Alternatives Almond milk, hemp milk, rice milk, Soy products, coconut cream oat milk Beverages Fruit and vegetable juices from Fruit and vegetable juices made high FODMAP foods (apple juice, from low FODMAP foods (orange grapefruit juice), coconut water, juice, tomato juice), coffee, herbal drinks with high-fructose corn syrup tea, water Condiments, High-fructose corn syrup, agave, honey, Balsamic vinegar, olive oil, soy Seasonings, most jams and jellies, relish, hummus, sauce, mayo, mustard, garlic infused Sweeteners artificial sweeteners, any sauces or oil, sugar, salt, pepper, most herbs, dressings made with high FODMAP small amounts of marinara sauces foods or high-fructose corn syrup To make an appointment with a gastroenterologist, visit henryford.com or call 1-800-HENRYFORD (436-7936). -

Freshly Made Smoothie and Juice $18.00 Start a Healthy Day With

Start a healthy day with Pierre's Freshly made Smoothie and Juice $18.00 Smoothies Juices Red Blast Watermill strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, lemon apple, carrot, beet, ginger Pineapple Boat Lemon Cleanse pineapple, banana, coconut milk, lemon juice apple, carrot, lemon, ginger Soy Sensation Gibson blueberries, banana, soy milk, agave pineapple, beet, kale, parsley, ginger Tropi-Kale Namaste kale, pineapple, mango, coconut milk apple, beet, cucumber, ginger St. Barth Sweet Greens pineapple, mango, grapefruit, low fat yogurt apple, cucumber, kale, celery Hangover Cure Pick Me Up banana, mango, low fat yogurt apple, carrot, orange, sweet red pepper What Diet Sagaponack honeydew, watermelon, vanilla ice cream apple, beet, asparagus Breakfast is served from 8am until 10:30 am every day, 7 days, 365 days Coupe de fruits de saison 14 Croissant or Danishes 7 Assorted fresh fruits 4 Slices of toasted baguette 4 3 Slices of toasted brioche (cut 1/2) 4 Coupe Parfait 16 3 Slices of toasted 7 Grains (cut 1/2) 4 Fat free Oikos Greek Yogurt, Fresh Fruits and Granola 2 English muffin (4 sides) 4 French toast 16 Jam from Alain Millat 2.50 With maple syrup, whipped cream and fresh berries Strawb, Apricot, Blueberry, Raspberry, Blood orange 1/2 Grapefruit 10 Pineapple Boat 10 Iced Tea 5 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice 5 Our cage free eggs are guaranteed 100% ORGANIC. Homemade lemonade with honey and mint 5 *2 eggs any style 16 Tomato Juice 5 Scrambled Sunny side up Over easy Roasted potatoes and baked tomato We use exclusively ILLY Coffee Served -

Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1969 Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content Anna Man-saw Liu Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Anna Man-saw, "Analysis of Fruit Juices and Drinks of Ascorbic Acid Content" (1969). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4851. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4851 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSTS OF FRUIT JUICES AND DRINKS OF ASCORBIC ACID CONTENT by Anna Man-saw Liu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Food and Nutrition UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY• Logan,1969 Utah ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sincere appreciation is expressed to Dr. Ethelwyn B. Wilcox, Head of the Food and Nutrition Department, for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Many thanks to Mrs. Ruth E. Wheeler, Assistant Professor of Food and Nutrition, for her able guidance on this research. Appreciation is also expressed to Dr. Harris 0 . Van Orden , Professor of Chemistry, for his many helpful suggestions and for serv ing as a committee member . Also sincere gratefulness to Dr . Deloy G. Hendricks, Assistant Professor of Food and Nutrition, for his many helps during the experimental procedures. The author wishes to express her gratitude to her husband , Mr . -

Crediting Smoothies for Grades K-12 in the NSLP and SBP

Crediting Smoothies for Grades K-12 in the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program This guidance applies to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA) meal patterns for grades K-12 in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), Seamless Summer Option (SSO) of the NSLP, and Afterschool Snack Program (ASP). For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods, refer to the Connecticut State Department of Education’s (CSDE) Menu Planning Guide for School Meals for Grades K-12, and visit the CSDE’s Meal Patterns for Grades K-12 in School Nutrition Programs and Crediting Foods in School Nutrition Programs webpages. Smoothie ingredients that credit toward the meal patterns for grades K-12 include full-strength vegetable juice and pureed vegetables (vegetables component); full-strength fruit juice and pureed fruits (fruits component); milk that meets the meal pattern requirements (milk component); and yogurt or soy yogurt (meat/meat alternates component). Creditable ingredients in smoothies must provide at least the minimum creditable amount to credit toward the meal patterns for grades K-12. The minimum creditable amounts are ⅛ cup for the vegetables component; ⅛ cup for the fruits component; ¼ cup for the milk component (applies to smoothies only); and ⅛ cup for yogurt. School food authorities (SFAs) must maintain appropriate documentation to indicate the crediting information for smoothies. For example, to credit a strawberry smoothie as ½ cup of the fruits component and 1 ounce equivalent of the meat/meat alternates component, the documentation must indicate that the serving contains ½ cup of pureed strawberries and ½ cup of yogurt. -

Tomato Juices and Tomato Juice Concentrates: a Study of Factors Contributing to Their Gross Viscosity

Tomato juices and tomato juice concentrates: a study of factors contributing to their gross viscosity CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0174 1715 m mi BISLI0T3BEK DER LANDPO'CVHOOKSCHOOL Promotor: dr. W. Pilnik, hoogleraar in delevensmiddelenlee r Co-promotor: dr. ir. A.G.J. Voragen, wetenschappelijk hoofdmedewerker ^JfVJO ??oi,'^' R. Heutink Tomato juices and tomato juice concentrates: a study of factors contributing to their gross viscosity Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de landbouwwetenschappen, op gezag van de rector magnificus, dr. C.C. Oosterlee, in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 8 oktober 1986 des namiddags te vier uur in de aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen H i / 0' J ^u9p?o, , fo9 STELLINGEN 1. Dedoo r Shomer et al. (1984) gesussereerde rol van endogeen cellulase bij het uitzakken van deeltjes in tomatensap wordt niet ondersteund door de in de literatuurvermeld ecellulas ehoeveelhede ni nd etomaat . Shomer,I. ,P . Lindnere nR . Vasiliver,198 4 Journalo f FoodScience ,49:628-63 3 2. Geziend egroott eva nd edeeltje s ishe ttwijfelachti g of Raoe t al.(1986 )d ejuist e meetgeometriegebruike nvoo r hunrheologisch e metingenaa n appelmoes. Rao, M.A., H.J.Cooley ,J.N .Nogueir ae nM.R .McLellan ,198 6 Journalo f FoodScience , 51:176—179 3. Bij het gebruik van polysaccharide-afbrekende enzymente r opheldering van de structuurva npolysaccharide n moetmee raandach tworde n besteed aan: 1)d ezuiverhei dva n hetenzym , 2)d ezuiverhei dva nd esubstrate ndi e worden gebruiktvoo r het karakteriserenva nhe tenzy me n3 )ee nmogelijk emultisubstraa t specificiteitva nhe tenzym . -

Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Tomatoes and Tomato Products

Complete Guide to Home Canning Guide 3, Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Tomatoes and Tomato Products (NOTE: This electronic version of the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning was created by Utah State University Extension and reviewed by Charlotte Brennand, Extension Food and Nutrition Specialist at Utah State University, July 1995. Salsa recipes developed at Washington State University have been added as a supplement, with permission of Washington State University. The supplement on salsas is based on Salsa Recipes for Canning, PRN395, by Val Hillers, a food specialist, and Richard H. Dougherty, a food processing specialist, both with the Washington State University Cooperative Extension, Dept. of Food Science and Human Nutrition. They were assisted by Barry Swanson and Mike Costello in the development of the recipes.) Table of Contents Section Page General .................................................................... 1 Tomato juice................................................................ 1 Tomato and vegetable juice blend ............................................... 2 Tomatoes—crushed.......................................................... 3 Standard tomato sauce ....................................................... 5 Tomatoes—whole or halved (packed in water) ..................................... 6 Tomatoes—whole of halved (packed in tomato juice) ................................ 7 Tomatoes—whole or halved (packed raw without added liquid) ........................ 8 Tomatoes with okra or zucchini ................................................ -

Orange Juice Apple Juice Cranberry Juice Grape Juice Tomato Juice

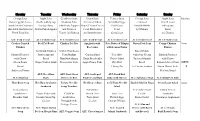

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Orange Juice Apple Juice Cranberry Juice Grape Juice Tomato Juice Orange Juice Apple Juice Breakfast Bacon Egg & Cheese Waffle with Syrup Breakfast Bake Cream of Wheat Scrambled Eggs Oatmeal French Toast Sandwich on Croissant Sausage Patty with Ham, Peppers Bagel/Cream Cheese Fried Ham English Muffin with Syrup Shredded Hashbrowns Warm Baked Apples and Potatoes Fresh Blueberries Toast 1/2 Banana Bacon Fresh Fruit Mix Toast/ 1/2 Banana and Strawberries Cantaloupe 1/2 Banana ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal ALT: Cold Cereal Cracker Crusted Beef Pot Roast Chicken Pot Pies Spaghetti with Beer Battered Tilapia Bacon Pork Loin Crispy Chicken Dinner Chicken Beef Sauce with Lemon/Tartar Dinner Au Gratin Potatoes Yellow Wax Beans Baked Potato Mashed Potatoes Brussel Sprouts Corn Muffins Garden Salad Cole Slaw with Sour Cream Mashed Potatoes with Gravy Bread Mini Butterfinger Garlic Breadsticks Potato Salad Buttered Squash with Gravy Green Beans Grape Walnut Salad Cheesecake Torte Apple Dump Cake Rye Roll Bread Buttered Sweet Corn WEEK Bread Cherry Pie Ice Cream Sundaes Warm Dinner Rolls 1 Ambrosia Freeze Monkey Bread ALT: Root Beer ALT: Beef Chow ALT: Scalloped ALT: Fried Brat ALT: Meatloaf Ham Mein over Rice Potatoes and Ham Patty with Onions ALT: Salisbury Steak ALT: BBQ Pork Ribs Ham Bean Soup Hot Ham & Cheese Turkey Noodle Hot Dog on Bun Cold Tuna Noodle English Muffin Pizza Seven Layer Salad Supper Sandwich Soup/ Crackers -

Mixing up Bloody Marys New York Bartenders Are Creating Surprising Riffs on the Popular Brunch Drink

Mixing Up Bloody Marys New York bartenders are creating surprising riffs on the popular brunch drink. BY ELIN McCOY PHOTOGRAPH BY ZACHARY ZAVISLAK familiar drink in eccentric ways. WD- 50’s Proud Mary is pink and carbon- ated. Spins at The Rum House include UNDER THE WATCHFUL EYE OF A a version that uses white rye whiskey puckish old king, bartender Bill Dante instead of vodka and is garnished with lines up six different Bloody Marys a slice of spicy salami. The only con- on the smooth, polished wood. The stant ingredient is tomato juice. St. Regis hotel’s King Cole Bar—with At King Cole, one variation relies its famous Maxfield Parrish mural on smoky single malt, and another as backdrop—is where the ultimate features gin and clam juice. My fa- brunch drink was probably introduced vorite—the subtle Mary Terranean, to America more than 75 years ago. which is smoothed with olive oil—also What better starting point to assess got the vote of Jeffrey Pogash, author Manhattan’s new riffs on the recipe? of Bloody Mary (Thornwillow, 2011), The original Bloody Mary, called who was tagging along to offer advice. the Red Snapper at the King Cole “A good Bloody has to be a balance be- Bar, was a tangy mix of tomato juice, tween spice, spirit, bite and texture,” vodka, Worcestershire sauce, lemon Pogash says as we head downtown to juice, salt and cayenne pepper. Now, try more. DRINKS bartenders are transforming the At Prune, we find 10 offerings. The refreshing Classic beats other versions, such as the Caesar, which is made with gin and a pickled egg. -

Tomato Juice (Pet)

TOMATO JUICE (PET) Case Code Pack & Size 18953 8/ 32 oz. Campbell's® Tomato Juice is America's favorite tomato juice! It contains 100% tomato juice, provides more than 1 cup of vegetables per can and is a good source of vitamin C and vitamin A as Beta Carotene. Nutritional Facts FEATURES AND BENEFITS PREPARATION Serving Size 8 FL OZ (240 ML ) Campbell's® Tomato Juice is America's favorite tomato Simply chill, shake well, Amount Per Serving juice! It contains 100% tomato juice, provides 1 cup of and serve. vegetables per 8 fl oz. and is a good source of vitamin C Calories 50 Calories from Fat 0 HANDLING and vitamin A as Beta Carotene. % Daily Value REFRIGERATE ANY 0% SERVING IDEAS Total Fat 0g UNUSED PORTION. STORAGE 0% Campbell's® Tomato Juice can be used as a mix in mocktails Saturated Fat 0g or cocktails. It is great as a base for sauces and soups as Shelf Life: 12 MONTHS Cholesterol 0% 0mg well. Enjoy it on its own or with a twist of lime over ice. 28% Sodium 670mg Storage Temperature: 65F 3% Total Carbohydrate 10mg MORE 8% Dietary Fiber 2g Campbell's® Tomato Juice is America's favorite tomato juice! It contains 100% tomato 12% Sugars 6g juice, provides 1 cup of vegetables per 8 fl oz. and is a good source of vitamin C and 4% Protein 2g vitamin A as Beta Carotene. Vitamin A 20% Vitamin C 120% PACKAGING DETAILS Calcium % Iron % Pack & Size: Case Weight: UPC: 8/ 32 oz. 18.870 LB 51000002853 Vitamin E 0% Thiamine 0% 15.250IN x 7.750IN x Cube: Case Size: SCC-14: Magnesium 0% Zinc 0% .560 FT 8.188IN 10051000189537 * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie (L x W x H) diet. -

Livefit SMOOTHIE RECIPES!

LiveFit SMOOTHIE RECIPES! Beet Blaster: 2 medium-sized beets, w/tops, 3 carrots and 1 apple cored. Even if you don’t like beets, you have to give this juice a try! The apple and carrot are sweet and balance the earthy beet flavor. Beets are a super-food that helps detoxify the skin and kidneys, contain important folic acid, and are filled with betacyanin that’s known to prevent cancers and increase exercise endurance. Green Machine: ½ bunch of kale, 1 cucumber, 1 ¼ cup pineapple. So refreshing and delicious you won’t believe you’re drinking kale! The sweetness of the pineapple makes this drink feel like a treat. The green machine is filled with vitamin B and iron that leaves you energized and ready to take on the world. The Healthy Mary: 2 large tomatoes, ½ cucumber, 4 stalks celery, ¼ cup cilantro, 1 jalapeno seeded, ¼ lemon, peeled. This is the Bloody Mary’s healthy sister! You haven’t had real tomato juice until you have made it fresh and add a little kick to spice things up. Tomatoes are rich in beta-carotene and lycopene both known to reduce the risk of heart disease and strokes. Garden Party: 5 cups spinach, 1 apple, ¼ cup parsley, 1 green pepper, & 3 carrots. Get your garden party on with this veggie-packed glass! The beauty of juicing is that when you use carrot or apple, the other super healthy but strong flavors such as parsley and green pepper aren’t as pronounced. Snake Bite: 3 carrots, 1” ginger, peeled, 1 apple. One of the first juices that Hope ever made and still her kid’s favorite. -

Fruitco Fruit Juice Nutrition Information

FruitCo Fruit Juice Nutrition Information APPLE+ 10 Fruits + Apple Mango Banana + Average Quantity Per 250mL %DI* Per 250mL Average Quantity Per 250mL %DI* Per 250mL Average Quantity Per 250mL %DI* Per 250mL Energy 468kJ 6% Energy 468kJ 6% Energy 468kJ 6% Protein 1.2g 2% Protein 1.2g 2% Protein 1.2g 2% Fat – Total <1g 0% Fat – Total <1g 0% Fat – Total <1g 0% - Saturated <1g 1% - Saturated <1g 1% - Saturated <1g 1% Carbohydrate 27.5g 9% Carbohydrate 27.5g 9% Carbohydrate 27.5g 9% - Sugars 26.8g 30% - Sugars 26.8g 30% - Sugars 26.8g 30% Dietary Fibre 2.5g 8% Dietary Fibre 2.5g 8% Dietary Fibre 2.5g 8% Sodium 12mg 1% Sodium 12mg 1% Sodium 12mg 1% Vitamin C 25mg 62%(†RDI) Vitamin C 25mg 62%(†RDI) Vitamin C 25mg 62%(†RDI) *Percentage Daily Intakes are based on an average adult diet of 8,700kJ. *Percentage Daily Intakes are based on an average adult diet of 8,700kJ. *Percentage Daily Intakes are based on an average adult diet of 8,700kJ. Your daily intakes may be higher or lower depending on your energy needs. Your daily intakes may be higher or lower depending on your energy needs. Your daily intakes may be higher or lower depending on your energy needs. †Recommended Dietary Intake †Recommended Dietary Intake †Recommended Dietary Intake Ingredients Ingredients Ingredients Reconstituted Apple Juice (99%), Dietary Fibre (Acacia), Natural Reconstituted Fruit Juices [Apple (76.5%), Orange (10%), Grape (4%), Reconstituted Juices [Apple (93%), Mango Puree (5%), Banana Flavour, Food Acid (Citric), Natural Flavour, Vitamin C. -

Msuspcsbs Cala Calavogrow6.Pdf

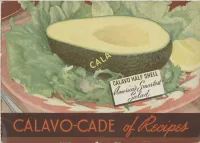

There is a new word in the Homemakers' dictionary because of their superb eating and keeping qualities — "CALAVO," criterion of quality and password to and nutritional values. perfection among fruits of the avocado family. Yet, Fruits measuring up to this quality standard are the avocado itself is by no means a new discovery. stamped "Calavo" by the growers' own association, Coursing the rich veins of New World history from but only after passing rigid requirements. the time of Columbus, the story of the avocado—the popular "new" fruit now grown in such abundance CALAVO-FOR YOUR PROTECTION in California—is a romantic album of four centuries Before picking, sample fruit are tested in the Calavo of adventure. Growers' laboratory to assure full maturity. After Four hundred years ago the explorers of tropical picking, every fruit is individually inspected and Latin America wrote picturesquely of the strange fruit graded. Only those passing the very highest tests are they found flourishing in their paths. "It is like butter, stamped "Calavo". then carefully packed to reach and is of marvelous flavor, so good and pleasing to your grocer with all their grove-fresh goodness. The the palate that it is a marvelous thing," and "it nour- trademark "Calavo" is stamped only on the finest ished and strengtheneth the body, corroborating the fruit of the best 1 4 of the 99 avocado varieties. vital spirits and procuring vigor exceedingly." Remember, when buying avocados — appearance is Today, after years of importation, scientific testing, no guide to flavor. For your protection, demand the and experimental culture, California growers have expertly-selected fruit stamped "Calavo," Califor- developed a few varieties worthy to be set apart nia's finest avocados.