1 MOVING PEOPLES in the EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE1 by Greg WOOLF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roman Empire

S1 SOCIAL SUBJECTS Home Learning Booklet Angus Lauder WHEC S1 SOCIAL SUBJECTS HOME LEARNING This workbook has been created to support you with your social subjects learning at home. Please complete work at a pace that suits you and your family. Also, we understand that you have many different subjects sending you work and need to manage your time to complete work for all subjects. We would recommend completing 1 or 2 tasks per week - some will take longer than others. As you complete a task, you can email it to your teacher (email addresses below). This will allow your teacher to give you feedback. You can attach your work as a word document or take a picture of work you have handwritten. If you have any questions, we are also working from home, and will reply to any emails you send. Our email addresses are listed below: Mr Sinclair – [email protected] Ms Oliver – [email protected] Mrs Millar – [email protected] Mr Lauder – [email protected] 1 Contents History: The Romans 1. Curriculum Links 2. History Skills 3. The Growth of Rome 4. The People of Rome 5. The Roman Empire 6. The Roman Army 7. Life in the Roman Army 8. Roman Slavery 9. Roman Food 10. Just for Fun Curriculum for Excellence Level 3 2 • I can describe the factors contributing to a major social, political, or economic change in the past and can assess the impact on people’s lives. SOC 3-05a • I can use my knowledge of a historical period to interpret the evidence and present an informed view. -

Running Head: the TRAGEDY of DEPORTATION 1

Running head: THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 1 The Tragedy of Deportation An Analysis of Jewish Survivor Testimony on Holocaust Train Deportations Connor Schonta A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ David Snead, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Christopher Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mark Allen, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 3 Abstract Over the course of World War II, trains carried three million Jews to extermination centers. The deportation journey was an integral aspect of the Nazis’ Final Solution and the cause of insufferable torment to Jewish deportees. While on the trains, Jews endured an onslaught of physical and psychological misery. Though most Jews were immediately killed upon arriving at the death camps, a small number were chosen to work, and an even smaller number survived through liberation. The basis of this study comes from the testimonies of those who survived, specifically in regard to their recorded experiences and memories of the deportation journey. This study first provides a brief account of how the Nazi regime moved from methods of emigration and ghettoization to systematic deportation and genocide. Then, the deportation journey will be studied in detail, focusing on three major themes of survivor testimony: the physical conditions, the psychological turmoil, and the chaos of arrival. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

A Unified Concept of Population Transfer

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 21 Number 1 Fall Article 4 May 2020 A Unified Concept of opulationP Transfer Christopher M. Goebel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Christopher M. Goebel, A Unified Concept of Population Transfer, 21 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 29 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Unified Concept of Population Transfer CHRISTOPHER M. GOEBEL* Population transfer is an issue arising often in areas of ethnic ten- sion, from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Western Sahara, Tibet, Cyprus, and beyond. There are two forms of human population transfer: removals and settlements. Generally, commentators in interna- tional law have yet to discuss the two together as a single category of population transfer. In discussing the prospects for such a broad treat- ment, this article is a first to compare and contrast international law's application to removals and settlements. I. INTRODUCTION International attention is focusing on uprooted people, especially where there are tensions of ethnic proportions. The Red Cross spent a significant proportion of its budget aiding what it called "displaced peo- ple," removed en masse from their abodes. Ethnic cleansing, a term used by the Serbs, was a process of population transfer aimed at removing the non-Serbian population from large areas of Bosnia-Herzegovina.2 The large-scale Jewish settlements into the Israeli-occupied Arab territories continue to receive publicity. -

Mass Displacement in Post-Catastrophic Societies: Vulnerability, Learning, and Adaptation in Germany and India, 1945–1952

Futures That Internal Migration Place-Specifi c Introduction Never Were and the Left Material Resources MASS DISPLACEMENT IN POST-CATASTROPHIC SOCIETIES: VULNERABILITY, LEARNING, AND ADAPTATION IN GERMANY AND INDIA, 1945–1952 Avi Sharma The summer of 1945 in Germany was exceptional. Displaced persons (UN DPs), refugees, returnees, ethnic German expellees (Vertriebene)1 and soldiers arrived in desperate need of care, including food, shelter, medical attention, clothing, bedding, shoes, cooking utensils, and cooking fuel. An estimated 7.3 million people transited to or through Berlin between July 1945 and March 1946.2 In part because of its geographical location, Berlin was an extreme case, with observers estimating as many as 30,000 new arrivals per day. However, cities across Germany were swollen with displaced persons, starved of es- sential supplies, and faced with catastrophic housing shortages. During that time, ethnic, religious, and linguistic “others” were frequently conferred legal privileges, while ethnic German expellees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) were disadvantaged by the occupying forces. How did refugees, returnees, DPs, IDPs and other migrants navigate the fractured governmentality and allocated scar- city of the postwar regime? How did survivors survive the postwar? The summer of 1947 in South Asia was extraordinary in diff erent ways.3 Faced with a hastily organized division of the Indian sub- continent into India and Pakistan (known as the Partition), between 10 and 14 million Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus crossed borders in a period of only a few months. Estimates put the one-day totals for 2 Angelika Königseder, cross-border movement as high as 400,000, and data on mortality Flucht nach Berlin: Jüdische Displaced Persons 1945– 4 range between 200,000 and 2 million people killed. -

The Denaturalization and Deportation of Nazi Criminals: Is It Constitutional

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 4 1-1-1989 The Denaturalization and Deportation of Nazi Criminals: Is It Constitutional Norine M. Winicki Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Norine M. Winicki, The Denaturalization and Deportation of Nazi Criminals: Is It Constitutional, 11 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 117 (1989). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol11/iss1/4 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENTS The Denaturalization and Deportation of Nazi Criminals: Is It Constitutional? I. INTRODUCTION On June 22, 1941, Adolf Hitler launched an invasion of the So- viet Union.1 Under the plan for this attack, known as Operation Bar- barossa, Russia was to become an eastern annex of the German Reich, helping to consolidate Hitler's plan of a master Aryan race. 2 Consequently, Operation Barbarossa had two objectives, the military conquest of the Soviet Union and the extermination of Soviet Jews.3 The group whose responsibility it was to effectuate the elimination of the Jews in Russia were mobile killing units of SS troops called 4 Einsatzgruppen. In carrying out Operation Barbarossa, Hitler and his army set out to conquer the Baltic countries of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia.5 In Latvia, the Einsatzgruppen formed the locals into the Arjs Kom- mando whose only purpose was to kill all the Jews of Latvia.6 In 1942, an Einsatzgruppe A report to Berlin stated, "'The number of Jews in Latvia in 1935 was 93,479-4.79 percent of the entire popula- tion ... -

Expelled Nazis Paid Millions in Social Security

Expelled Nazis paid millions in Social Security By DAVID RISING, RANDY HERSCHAFT and RICHARD LARDNEROctober 19, 2014 9:17 PM OSIJEK, Croatia (AP) — Former Auschwitz guard Jakob Denzinger lived the American dream. His plastics company in the Rust Belt town of Akron, Ohio, thrived. By the late 1980s, he had acquired the trappings of success: a Cadillac DeVille and a Lincoln Town Car, a lakefront home, investments in oil and real estate. Then the Nazi hunters showed up. In 1989, as the U.S. government prepared to strip him of his citizenship, Denzinger packed a pair of suitcases and fled to Germany. Denzinger later settled in this pleasant town on the Drava River, where he lives comfortably, courtesy of U.S. taxpayers. He collects a Social Security payment of about $1,500 each month, nearly twice the take-home pay of an average Croatian worker. Denzinger, 90, is among dozens of suspected Nazi war criminals and SS guards who collected millions of dollars in Social Security payments after being forced out of the United States, an Associated Press investigation found. The payments flowed through a legal loophole that has given the U.S. Justice Department leverage to persuade Nazi suspects to leave. If they agreed to go, or simply fled before deportation, they could keep their Social Security, according to interviews and internal government records. Like Denzinger, many lied about their Nazi pasts to get into the U.S. following World War II, and eventually became American citizens. Among those who benefited: —armed SS troops who guarded the Nazi network of camps where millions of Jews perished. -

Punishments and the Conclusion of Herodotus' Histories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library Punishments and the Conclusion of Herodotus’ Histories William Desmond NE MUST CONSIDER the end of every affair, how it will turn out.”1 Solon’s advice to Croesus has often been Oapplied to Herodotus’ Histories themselves: Is the con- clusion of Herodotus’ work a fitting and satisfying one? Older interpretations tended to criticize the final stories about Ar- tayctes and Artembares as anticlimactic or inappropriate: Did Herodotus forget himself here, or were the stories intended as interludes, preludes to further narrative?2 Entirely opposite is the praise accorded Herodotus in a recent commentary on Book 9: “The brilliance of Herodotus as a writer and thinker is mani- fest here, as the conclusion of the Histories both brings together those themes which have permeated the entire work and, at the same time, alludes to the new themes of the post-war world.” 3 More recent appreciation for Herodotus’ “brilliance,” then, is often inspired by the tightly-woven texture of Herodotus’ narrative. Touching upon passion, revenge, noble primitivism, 1 Hdt. 1.32: skop°ein d¢ xrØ pantÚw xrÆmatow tØn teleutÆn, kª épobÆsetai (text C. Hude, OCT). 2 For summaries of earlier assessments (Wilamowitz, Jacoby, Pohlenz, et al.) see H. R. Immerwahr, Form and Thought in Herodotus (Cleveland 1966) 146 n.19; D. Boedeker, “Protesilaos and the End of Herodotus’ Histories,” ClAnt 7 (1988) 30–48, at 30–31; C. Dewald, “Wanton Kings, Picked Heroes, and Gnomic Founding Fathers: Strategies of Meaning at the End of Herodotus’ Histories,” in D. -

Ancient Rome

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Ancient Julius Caesar Rome Reader Caesar Augustus The Second Punic War Cleopatra THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. Ancient Rome Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

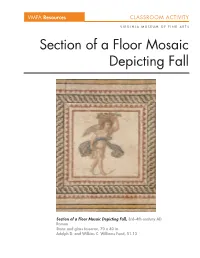

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

The Edictum Theoderici: a Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy

The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy By Sean D.W. Lafferty A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Sean D.W. Lafferty 2010 The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy Sean D.W. Lafferty Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This is a study of a Roman legal document of unknown date and debated origin conventionally known as the Edictum Theoderici (ET). Comprised of 154 edicta, or provisions, in addition to a prologue and epilogue, the ET is a significant but largely overlooked document for understanding the institutions of Roman law, legal administration and society in the West from the fourth to early sixth century. The purpose is to situate the text within its proper historical and legal context, to understand better the processes involved in the creation of new law in the post-Roman world, as well as to appreciate how the various social, political and cultural changes associated with the end of the classical world and the beginning of the Middle Ages manifested themselves in the domain of Roman law. It is argued here that the ET was produced by a group of unknown Roman jurisprudents working under the instructions of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic the Great (493-526), and was intended as a guide for settling disputes between the Roman and Ostrogothic inhabitants of Italy. A study of its contents in relation to earlier Roman law and legal custom preserved in imperial decrees and juristic commentaries offers a revealing glimpse into how, and to what extent, Roman law survived and evolved in Italy following the decline and eventual collapse of imperial authority in the region. -

Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-Determination Conflicts?

Can Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-determination Conflicts? A European Perspective Stefan Wolff Department of European Studies University of Bath Bath BA2 7AY England, UK [email protected] Introduction Self-determination conflicts are among the most violent forms of civil wars that can engulf modern societies. As they are in most cases linked to claims of ethnic, religious, linguistic or otherwise defined groups for secession from, or for political domination in, an existing state they also have repercussions on regional and international stability. Self-determination conflicts can be observed on all continents. Not all of them are violent, but most have a clear potential for violent escalation and are therefore an important concern for international and regional governmental organisations seeking to preserve peace and stability. However, the capacity of organisations like the UN, the OSCE and the EU to do so has only gradually developed over the past decade and is still a far cry from being sufficient. In the past and present, states (and population groups within them) have therefore felt that they had been and are left to their own devices when it comes to preserving their internal stability and external security. The largely incongruent political and ethnic maps of Europe have meant that self- determination conflicts on this continent have mostly taken the form of ethnic conflicts: from Northern Ireland to the Caucasus, from the Basque country to the Åland islands and from Kosovo to Silesia the competing claims of distinct ethnic groups to self-determination have been the most prominent sources of conflicts within and across state boundaries.