Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS of ST. PIUS X's DECREE on FREQUENT COMMUNION JOHN A

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF ST. PIUS X's DECREE ON FREQUENT COMMUNION JOHN A. HARDON, SJ. West Baden College HPHE highest tribute to the apostolic genius of St. Pius X was paid by * his successor on the day he raised him to the honors of the altar: "in the profound vision which he had of the Church as a society, Pius X recognized that it was the Blessed Sacrament which had the power to nourish its intimate life substantially, and to elevate it high above all other human societies." To this end "he overcame the prejudices springing from an erroneous practice and resolutely promoted frequent, even daily, Communion among the faithful," thereby leading "the spouse of Christ into a new era of Euchari^tic life."1 In order to appreciate the benefits which Pius X conferred on the Church by his decree on frequent Communion, we might profitably examine the past half-century to see how the practice which he advo cated has revitalized the spiritual life of millions of the faithful. Another way is to go back in history over the centuries preceding St. Pius and show that the discipline which he promulgated in 1905 is at once a vindication of the Church's fidelity to her ancient traditions and a proof of her vitality to be rid of whatever threatens to destroy her divine mission as the sanctifier of souls. The present study will follow the latter method, with an effort to cover all the principal factors in this Eucharistic development which had its roots in the apostolic age but was not destined to bear full fruit until the present time. -

The Origins of Old Catholicism

The Origins of Old Catholicism By Jarek Kubacki and Łukasz Liniewicz On September 24th 1889, the Old Catholic bishops of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany signed a common declaration. This event is considered to be the beginning of the Union of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches, federation of several independent national Churches united on the basis of the faith of the undivided Church of the first ten centuries. They are Catholic in faith, order and worship but reject the Papal claims of infallibility and supremacy. The Archbishop of Utrecht a holds primacy of honor among the Old Catholic Churches not dissimilar to that accorded in the Anglican Communion to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Since the year 2000 this ministry belongs to Archbishop JorisVercammen. The following churches are members of the Union of Utrecht: the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands, the Catholic Diocese of the Old Catholics in Germany, Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland, the Old Catholic Church of Austria, the Old Catholic Church of the Czech Republic, the Polish-Catholic Church and apart from them there are also not independent communities in Croatia, France, Sweden, Denmark and Italy. Besides the Anglican churches, also the Philippine Independent Church is in full communion with the Old Catholics. The establishment of the Old Catholic churches is usually being related to the aftermath of the First Vatican Council. The Old Catholic were those Catholics that refused to accept the doctrine of Papal Infallibility and the Universal Jurisdiction. One has to remember, however, that the origins of Old Catholicism lay much earlier. We shouldn’t forget, above all, that every church which really deserves to be called by that name has its roots in the church of the first centuries. -

St. Francis of Assisi Parish ! ! !! ! the Catholic Community in Weston ! Sunday, Aug

35 NǐǓLJNJdžǍDž RǐǂDž ! WdžǔǕǐǏ, CǐǏǏdžDŽǕNJDŽǖǕ 06883 ! ST. FRANCIS! We extend a warm welcome to all who ! worship at our church! We hope that you ! will find our parish community to be a place ! where your faith is nourished. ! OF ASSISI ! ! Rectory: 203 !227 !1341 FAX: 203 !226 !1154 Website: www.stfrancisweston.org Facebook: Saint Francis of Assisi ! The PARISH! Catholic Community in Weston Religious Education/Youth Ministry: ! ! 203 !227 !8353 THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITY IN WESTON Preschool: 203 !454 !8646 ! ! RdžDŽǕǐǓǚ OLJLJNJDŽdž HǐǖǓǔ ! August 4, 2019 Monday Through Friday 9:00 a.m. ! 4:00 p.m. ! SǖǏDžǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! Saturday Vigil ! 5:00 P.M. Sundays 8:00, 9:30 ! Family Mass, 11:00 A.M. 5:00 p.m. Scheduled Weekly ! Except for Christmas & Easter. ! WdždžnjDžǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! Monday ! Friday ! 7:30 A.M. Saturday & Holidays ! 9:00 A.M. ! HǐǍǚ Dǂǚ Mǂǔǔdžǔ ! 7:30 A.M. , Noon , 7:00 P.M. ! NǐǗdžǏǂ ! Novena prayers in honor of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal every Saturday following the 9:00 A.M. Mass. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ RdžDŽǐǏDŽNJǍNJǂǕNJǐǏ ! Saturdays, 4:00 !4:45 P.M.; Sundays 4:00 P.M. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ BǂǑǕNJǔǎ ! The Sacrament of Baptism is offered every Sunday at 12:00 noon. Please make arrangements for the Pre !Baptismal instructions after the birth of the child in person at the rectory. Pre !instruction for both parents is required. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ MǂǕǓNJǎǐǏǚ ! Arrangements must be made at the rectory in person by the couple. Where possible, arrangements should be made one year in advance and no later than six months. ! SǂDŽǓǂǎdžǏǕ OLJ AǏǐNJǏǕNJǏLj ! Communal anointings of the sick are celebrated. -

Irenaeus Shed Considerable Light on the Place of Pentecostal Thought for Histories That Seek to Be International and Ecumenical

Orphans or Widows? Seeing Through A Glass Darkly By Dr. Harold D. Hunter Abstract Scholars seeking to map the antecedents of Pentecostal distinctives in early Christendom turn to standard reference works expecting to find objective summaries of the writings of Church Fathers and Mothers. Apparently dismissing the diversity of the biblical canon itself, the writers of these reference works can be found manipulating patristic texts in ways which reinforce the notion that the Classical Pentecostal Movement is a historical aberration. This prejudice is evident in the selection of texts and how they are translated and indexed as well as the surgical removal of pertinent sections of the original texts. This problem can be set right only by extensive reading of the original sources in the original languages. The writings of Irenaeus shed considerable light on the place of Pentecostal thought for histories that seek to be international and ecumenical. Introduction I began advanced study of classical Pentecostal distinctives at Fuller Theological Seminary in the early 1970s. Among those offering good advice was the then academic dean of Vanguard University in nearby Costa Mesa, California, Russell P. Spittler. While working on a patristic project, Spittler emphasized the need for me to engage J. Quasten and like scholars. More recently I utilized Quasten et al in dialogue with William Henn in a paper presented to the International Roman Catholic - Pentecostal Dialogue which convened July 23-29, 1999 in Venice, Italy. What follows is the substance of the paper delivered at that meeting.i The most influential editions of Church Fathers and Mothers available in the 20th Century suffered from inadequate translation of key passages. -

Thehebrewcatholic

Publication of the Association of Hebrew Catholics No. 78, Winter Spring 2003 TheTheTheTheTheThe HebrewHebrewHebrewHebrewHebrewHebrew CatholicCatholicCatholicCatholicCatholicCatholic “And so all Israel shall be saved” (Romans 11:26) Our new web site http://hebrewcatholic.org The Hebrew Catholic, No. 78, Winter Spring 2003 1 Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ International The Association of Hebrew Catholics aims at ending the alienation Founder of Catholics of Jewish origin and background from their historical Elias Friedman, O.C.D., 1916-1999 heritage, by the formation of a Hebrew Catholic Community juridi- Spiritual Advisor cally approved by the Holy See. Msgr. Robert Silverman (United States) The kerygma of the AHC announces that the divine plan of salvation President has entered the phase of the Apostasy of the Gentiles, prophesied by David Moss (United States) Our Lord and St. Paul, and of which the Return of the Jews to the Secretary Holy Land is a corollary. Andrew Sholl (Australia) Advisory Board Msgr. William A. Carew (Canada) “Consider the primary aim of the group to be, Nick Healy (United States) not the conversion of the Jews but the creation of a new Hebrew Catholic community life and spirit, Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ United States an alternative society to the old.” David Moss, President A counsel from Elias Friedman, O.C.D. Kathleen Moss, Secretary David Moss, (Acting) Treasurer The Association of Hebrew Catholics (United States) is a non-profit corpo- The Association of Hebrew Catholics is under the patronage of ration registered in the state of New York. All contributions are tax deduct- Our Lady of the Miracle ible in accordance with §501(c)(3) of the IRS code. -

Blaise Pascal: from Birth to Rebirth to Apologist

Blaise Pascal: From Birth to Rebirth to Apologist A Thesis Presented To Dr. Stephen Strehle Liberty University Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Course THEO 690 Thesis by Lew A. Weider May 9, 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 Chapter I. JANSENISM AND ITS INFLUENCE ON BLAISE PASCAL 12 The Origin of Jansenism . 12 Jansenism and Its Influence on the Pascals . 14 Blaise Pascal and his Experiments with Science and Technology . 16 The Pascal's Move Back to Paris . 19 The Pain of Loneliness for Blaise Pascal . 21 The Worldly Period . 23 Blaise Pascal's Second Conversion 26 Pascal and the Provincial Lettres . 28 The Origin of the Pensees . 32 II. PASCAL AND HIS MEANS OF BELIEF 35 The Influence on Pascal's Means of Belief 36 Pascal and His View of Reason . 42 Pascal and His View of Faith . 45 III. THE PENSEES: PASCAL'S APOLOGETIC FOR THE CHRISTIAN FAITH 50 The Wager Argument . 51 The Miracles of Holy Scripture 56 The Prophecies . 60 CONCLUSION . 63 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 65 INTRODUCTION Blaise Pascal was a genius. He was revered as a great mathematician and physicist, an inventor, and the greatest prose stylist in the French language. He was a defender of religious freedom and an apologist of the Christian faith. He was born June 19, 1623, at Clermont, the capital of Auvergne, which was a small town of about nine thousand inhabitants. He was born to Etienne and Antoinette Pascal. Blaise had two sisters, Gilberte, born in 1620, and Jacqueline, born in 1625. Blaise was born into a very influential family. -

Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017

The Holy Sacrament of Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017 Icon of Pentecost © by Monastery Icons – www.monasteryicons.com Used with permission. “Come Holy Spirit and inflame our hearts with the fire of divine love!” Darryl Adams 540-622-8073, [email protected] St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, Front Royal, VA A.M.D.G Table of Contents Weekly Class Schedule 5 Confirmation Preparation Entrance Questionnaire 6 Note to Parents 7 Specific Confirmation Prayers 8 Summary of the Faith of the Church 9 Summary of Basic Prayers 10 Preparation Checklist 12 Forms and Requirements (Final Requirements start on page 121) Confirmation Sponsor Certificate*1 14 Choosing a Patron Saint and Sponsor 16 Sponsor & Proxy Form* 19 Retreat from* 21 Patron Saint Report 23 Historical Report 24 Gospel Report 26 Apostolic Project 28 Apostolic Project Proposal Form 31 Apostolic Project Summary Form (2 pages) 33 THE EXISTENCE OF GOD 36 The Problem of Evil 39 Hell is Real 43 Guardian Angels including information from St. Padre Pio 47 Guardian Angel Litany 51 The Last Things 52 SACRED SCRIPTURE 55 Are the Books of the New Testament Reliable Historical Documents? 56 How do the Books of the New Testament indicate the manner in which they are supposed to be read? 57 Where the rubber hits the road… 59 How does the Church further instruct us on how to read the Holy Bible? 60 The Bottom Line 61 Diagram of Highlights of Christ’s Life 62 THE DIVINITY OF CHRIST AND THE HOLY TRINITY 63 What Jesus did and said can be done by no man 64 Who do people say that He is? 66 -

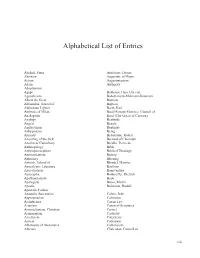

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews

Publication of the Association of Hebrew Catholics No. 79, Winter 2004 TheThe HebrewHebrew CatholicCatholic “And so all Israel shall be saved” (Romans 11:26) Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews Christ the King Church, Ann Arbor, Michigan Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ International The Association of Hebrew Catholics aims at ending the alienation Founder of Catholics of Jewish origin and background from their historical Elias Friedman, O.C.D., 1916-1999 heritage, by the formation of a Hebrew Catholic Community juridi- Spiritual Advisor cally approved by the Holy See. Msgr. Robert Silverman (United States) The kerygma of the AHC announces that the divine plan of salvation President has entered the phase of the Apostasy of the Gentiles, prophesied by David Moss (United States) Our Lord and St. Paul, and of which the Return of the Jews to the Secretary Holy Land is a corollary. Andrew Sholl (Australia) Advisory Board Msgr. William A. Carew (Canada) “Consider the primary aim of the group to be, Nick Healy (United States) not the conversion of the Jews but the creation of Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ United States a new Hebrew Catholic community life and spirit, David Moss, President an alternative society to the old.” Kathleen Moss, Secretary A counsel from Elias Friedman, O.C.D. David Moss, (Acting) Treasurer The Association of Hebrew Catholics (United States) is a non-profit corpora- The Association of Hebrew Catholics is under the patronage of tion registered in the state of New York and Michigan. All contributions are Our Lady of the Miracle tax deductible in accordance with §501(c)(3) of the IRS code. -

St. Peter Vicar of Christ, Prince of the Apostles

St. Peter St. Paul the Apostle Ex ossibus (particle of bone) Vicar of Christ, Prince of the Apostles Ex ossibus (particle of bone) Also known as: Saul of Tarsus. Also known as: Simon; Prince of the Apostles; Feasts: Cephas. 25 January (celebration of his conversion) Feasts: 29 June (feast of Peter 29 June (feast of Peter and Paul). and Paul) 22 February (feast of the Chair 18 November (feast of the of Peter, emblematic of the dedication of the Basilicas world unity of the Church). of Peter and Paul) 18 November (feast of the dedication of the Basilicas of Profile: Peter and Paul). Birth name was Saul. Was a Talmudic student and Pharisee, and a Tent-maker by trade. Profile: Hated and persecuted Christians as heretical, even assisting at the Fisherman by trade. Brother of stoning of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr. On his way to St. Andrew the Apostle who led Damascus to arrest another group of them, he was knocked to the him to Christ. Was renamed ground, struck blind by a heavenly light, and given the message that “Peter” (Rock) by Jesus to indicate that he would be the rock-like in persecuting Christians, he was persecuting Christ Himself. The foundation on which the Church would be built. Was the first Pope. experience had a profound spiritual effect on him, causing his Miracle worker. Martyr. conversion to Christianity. He was baptized, changed his name to Born: date unknown. Paul to reflect his new persona, and began traveling and preaching. Died: martyred circa 64 (crucified head downward because he claimed Martyr. -

1. Apostle Page 1

1. Apostle Page 1 1. APOSTLE Summary: 1. The apostles in the New Testament were chosen to be witnesses to the resurrection of Jesus Christ. They were sent to bring to the whole world the message of salvation in Christ. - 2. In his writings, De La Salle refers frequently to the New Testament apostles as the reference point for the traditional content of the Christian faith and as models for the zeal of the Brothers. - 3. De La Salle envisions the vocation of the Brother as succeeding in some way to the minis try of the apostles, especially in the catechizing of the poor. 4. Consequently, Lasaillan spiri tuality is an apostolic spirituality, integrating the elements of faith and zeal. J. THE MEANING OF THE WORD ment distinction when it defines an apostle vaguely as "someone who was a disciple of Jesus 1.1. The word is used almost exclusively in the Christ". The role of the Apostles is said to be "to meaning allached to it in the New Testament serve as a model for those who have embraced the scriptures. As derived from the Greek., apos/el/ein. ecclesiastical state". The dictionary also notes that the root meaning of the word refers to someone the term apostle had some currency as applied to who is sent or charged with a special mission. In comical persons, practical jokers, and libertines. It the . ew Testament the Apostles are chosen by goes without saying tbat these dictionary entries Jesus to carry on his mission to announce the neither do justice to tbe vocation and function of good news of the kingdom of God. -

JOHN HUGO and an AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY of NATURE and GRACE Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences of Th

JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Benjamin T. Peters UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May, 2011 JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Approved by: ________________________________________________________________ William Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _______________________________________________________________ Dennis Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ______________________________________________________________ Kelly Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Michael Baxter, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Benjamin Tyler Peters All right reserved 2011 iii ABSTRACT JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Tyler University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation examines the theological work of John Hugo by looking at its roots within the history of Ignatian spirituality, as well as within various nature-grace debates in Christian history. It also attempts to situate Hugo within the historical context of early twentieth-century Catholicism and America, particularly the period surrounding the Second World War. John Hugo (1911-1985) was a priest from Pittsburgh who is perhaps best known as Dorothy Day‟s spiritual director and leader of “the retreat” she memorialized in The Long Loneliness. Throughout much of American Catholic scholarship, Hugo‟s theology has been depicted as rigorist and even labeled as Jansenist, yet it was embraced by and had a great influence upon Day and many others.