Richard Ybarra 1970-1975 1980-1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Formation of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez's Bond

Robert F. Kennedy and the Farmworkers: The Formation of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez’s Bond By Mariah Kennedy Cuomo Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Edward L. Widmer April 7, 2017 !1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all who made this work possible. Writing this thesis was a wonderful experience because of the incredible and inspirational stories of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez, and also because of the enthusiasm those around me have for the topic. I would first like to thank Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez for their lasting impact on our country, and for the inspiration they provide to live with compassion. I would also like to thank the farm workers, for their heroism and strength in their fight for justice. I also would like to thank my thesis advisor, Ted Widmer, for his ongoing support throughout writing my thesis. Thank you for always pushing me to think deeper, and for helping me to discover new insights. Thank you to Ethan Pollock, for providing me with the tools to undertake this mission. Thank you to my mother, Kerry Kennedy, for inspiring me to take on this topic with the amazing work you do—you too, are an inspiration to me. Thank you for your ongoing guidance. Thank you to Marc Grossman, who was an amazing help and provided invaluable assistance in making this piece historically accurate. And finally, thank you to the incredible participants in the farm worker movement who took the time to speak with me. -

UFW Michigan Boycott Records

UFW Michigan Boycott Collection Papers, 1964-1981 (Predominantly, 1970s) 11 linear feet Accession # 221 DALNET # OCLC# The UFW Michigan Boycott collection contains materials specific to the state, and the activities of the UFW within the state. The largest boycott in Michigan was of California grapes, and this is reflected in the numerous store surveys which the UFW conducted in an attempt to ascertain the amount of non-UFW wine available. In addition, the collection contains a small amount of material about the lettuce boycott . The collection however, is far more than boycott material. There is a large quantity of material on agriculture and migrants, and their living and working conditions in the state. (In the 1970s Michigan had the third largest migrant population in the nation.) Additionally, staff activities (other than the boycott ) such as fundraising are documented. There is a significant amount of correspondence to Michigan businesses about UFW concerns, and correspondence which shows support for UFW by a wide range of groups including Michigan colleges and universities, churches, and unions, notably the UAW. PLEASE NOTE: Folders are computer-arranged alphabetically within each series in this finding aid, but may actually be dispersed throughout several boxes in the collection. Note carefully the box number for each folder heading. Important subjects in the collection: Agriculture Boycotts Migrant labor Important correspondents in the collection: Lupe Anguiano* Sam Baca* Mayor Jerome P. Cavanaugh Shirley Charbonneau* Cesar Chavez Richard Chavez UFW Michigan Boycott Collection - 2 - Senator Roger Craig John Conyers, Jr. John Dingell Gerald R. Ford Robert P. Griffin Senator Philip A. Hart Rev. -

Lesson 6: Cesar Chavez

Unit Two: Peacemakers and Nonviolence Lesson 6: Cesar Chavez Standards Addressed by Lesson: CIVICS Standard 4.3 Students know how citizens can exercise their rights (d). Standard 4.4 Students know how citizens can participate in civic life (a-d). HISTORY Standard 5.1 Students understand how democratic ideas and institutions in the United States have developed, changed, and/or been maintained (c-d). Standard 5.3 Students know how political power has been acquired, maintained, used and /or lost throughout history (e). Standard 6.2 Students know how societies have been affected by religions and philosophies (a). Objectives of lesson: To introduce and discuss Cesar Chavez and the issue of human rights. Instructional Strategies: Reading, active video watching, group discussion, group activity, writing. Preliminary Lesson Preparation: Educator should read the article, ―The Story of Cesar Chavez,‖ and view the video available from the Denver Public Library, The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers’ Struggle (DPL R01980 09463, 1 hour 45 minutes long).Suggested homework for the class the night before the lesson would be to have them read the article,―The Story of Cesar Chavez,‖ prepared by the Cesar Chavez Foundation. Suggested Resources to Obtain: -The movie, Cesar Chavez (Hispanic and Latin American Heritage Video Collection DPL R0220020917, Denver Public Library) -The movie, The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers’ Struggle Suggested Time: Around 80 minutes or two class periods but it is possible to narrow it to a 50 minute class Materials Needed: -Video -―The Universal Declaration of Human Rights‖ -―Have the Human Rights of the Workers Been Violated?‖ Attachments: A. -

Roland Palencia and Queer Oral History

CALIFRONIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE From Middle Class Guatemalan to U.S. Gay Latino Activist: Roland Palencia and Queer Oral History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies By David Medina Guzmán May 2014 The thesis of David Medina Guzmán is approved: ________________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Alicia Ivonne Estrada Date ________________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Marta López-Garza Date ________________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Mary S. Pardo, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my chair Dr. Mary Pardo for the continuous support of my thesis study and research, for her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Her guidance helped me complete the research and writing of this thesis. I would also like to thank the other thesis committee members: Dr. Alicia Ivonne Estrada and Dr. Marta López-Garza, for providing me with encouragement, insightful comments, and valuable knowledge. My course professors, Doctors Christina Ayala-Alcantar, Peter J. García, Jorge García, Rosemary González, Breny Mendoza, and Theresa Montaño: Muchas gracias for sharing your knowledge and always respecting us, the students! I would like to acknowledge everyone in my Chicana and Chicano Studies cohort/co-heart: Fatima Acuña, Jose Amaro, Juan Betts, Norma Franco, Jocelyn Gómez, Mónica Hernández, Eva Longoria, Bryant Partida, Selene Salas, Mario Tolentino, Annette Trujillo, and Clara Urionabarrenechea. I was truly blessed to have been surrounded by intelligent and awesome individuals! I will always treasure our hugs, smiles, and laughs, chisme during study sessions, birthday celebrations, coffee/tea and dinner dates, in-class conversations, and all the adventures we had in West Hollywood, Chicago, San Antonio, and Corpus Christi. -

A Response to My Critics

A Response to my critics Matt Garcia Professor of History and Transborder Studies Arizona State University In September 2012, the University of California Press published my book From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement. As is common in publishinG these days, it took time for the public to read and diGest the book. While more formal reviews are certain to come, several responses have beGun to trickle in, many privately to me as well as more public statements. A substantial number of these reviews have been very positive and encouraGinG, includinG those from a number of veterans of the movement and their families who believe the book rinGs true to their experiences and accurately captures the sacrifices they or their family members’ made for the United Farm Workers. AlthouGh I did not write the book with the intent of receiving such affirmation, I am honored many veterans find my book a worthy testament to their struggles. Not surprisingly, others have objected to my characterization of Cesar Chavez, and more Generally, the net results of his contributions to farm worker justice. This was expected given that the sources led me to a very different interpretation of his legacy than the one typically told. In fact, as I approached the publication of the book, the thorough editing process of the University of California Press prepared me for the backlash. Now that I have received it, I want to respond those who have chosen to take issue with my characterizations of Chavez, and more broadly, my interpretation of the history of the United Farm Workers. -

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised Edition

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised edition by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) The STory of PCUN aNd The farmworker movement iN oregoN Revised and Expanded by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) Eugene, Oregon July 2012 Front cover photograph: Mural in the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. Title page photograph: Tenth Anniversary Organizing Campaign, Brooks, Oregon, June 1995. Back cover: Mural on back wall of the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. © Lynn Stephen and pCUn, 2012 Written by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) 6201 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-6201 (541)346-5286 [email protected] http://cllas.uoregon.edu July 2012 Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN) 300 Young Street Woodburn OR 97071 (503) 982-0243 www.pcun.org [email protected] Production Alice Evans Research Dissemination Specialist Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies Proofing Eli Meyer, Assistant Director, CLLAS June Koehler, Research Assistant, CLLAS All photographs credited to PCUN unless otherwise noted The University of Oregon is an equal-opportunity, affirmative- action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. This publication will be made available in accessible formats upon request. 750 CopieS 2 The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Child in the field, 1995. -

UNITED FARM WORKERS of AMERICA TRADEMARK LICENSING FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQ) Version 5-18-2016

UNITED FARM WORKERS OF AMERICA TRADEMARK LICENSING FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQ) Version 5-18-2016 What are the UFW’s trademarks? A trademark right is a commercial right to market and/or sell goods or services bearing a word or symbol. UFW’s trademark registrations include SI SE PUEDE and the Eagle Mark. The UFW’s exclusive rights to use the SI SE PUEDE mark in commerce are protected by Federal Trademark Registration No. 2,212,951 and No. 4,781,659. The UFW’s exclusive rights to use the Eagle Mark in commerce are protected by Federal Trademark Registration No.090466. The “®” symbol appears on products bearing UFW’s registered marks. Sí Se Puede® What is the history of the UFW trademarks? EAGLE The UFW’s Eagle Mark is symbolic of the extensive goodwill and recognition built up by the UFW in the broader Latino and Hispanic communities. In 1962, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and others founded the National Farm Workers Association, later to become the United Farm Workers. That same year, Richard Chavez designed the UFW Eagle. Cesar told the story of the birth of the eagle. He asked Richard to design the flag, but Richard had problems making an eagle that he liked. Finally, he sketched one on a piece of brown wrapping paper. He then squared off the wing edges so that the eagle would be easier for union members to draw on the handmade red flags that would give courage to the farm workers with their own powerful symbol. Cesar made reference to the flag by stating, “A symbol is an important thing. -

Patty(Proctor)Park1970–1975

Patty (Proctor) Park 1970–1975 Solidarity: The House the UAW Built The United AutoWorkers and the United Farmworkers Detroit, Michigan 1972–1975 In November 1972, I arrived in Detroit to head up the small UFW boycott office there. I crossed the country with Janis Lien on Thanksgiving weekend, arriving at the downtown boycott house on a dull November day. I had been working at the union headquarters in La Paz for about nine months, after six years as a supporter in Toronto, Canada. Marshall Ganz and Jessica Govea encouraged me to join the union full time, and it was an easy decision with both of them working at La Paz. But in November of 1972 it was time to send organizers back out across the continent to beef up the resources of the lettuce boycott. In an interesting process that let us have some say in where we would be sent on the boycott we were asked to list three cities in order of preference. I can remember trying to figure out what to write down. I wasn’t an American so really didn’t have a lot of firsthand knowledge to go on. My first choice was Detroit. I knew it was a working people’s city, but most important, that Solidarity House, the UAW International Headquarters, was there. The UAW had been a strong supporter of the UFW. The UAW president Walter Reuther had been one of the first union leaders to come to California in support of the Delano grape strike. It was a progressive and politically active union. -

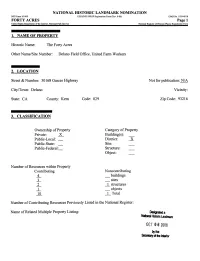

OCT 062008 by the Secretary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 FORTY ACRES Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: The Forty Acres Other Name/Site Number: Delano Field Office, United Farm Workers 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 30168 Garces Highway Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Delano Vicinity: State: CA County: Kern Code: 029 Zip Code: 93216 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: _X Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing _ buildings _ sites 1 structures _ _ objects 10 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: National Historic Landmark OCT 062008 by the Secretary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORTY ACRES Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Richard Ybarra, “Legacy of Cesar Chavez” 2006

Legacy of Cesar Chavez by Richard Ybarra Published in: Vida Nueva, February 2, 2006 Introduction As we prepare to celebrate another spring of our lives and the review of memories and lessons of Cesar Chavez, I am offering some personal perspectives and reflections that I have never written before now. Though I have many recollections of his teachings and example, in this column I will share my remembrances of my time with Cesar and my observations of his family and movement lives, which were one and the same. While Cesar Chavez Day festivities and events usually celebrate his deeds and achievements, this piece will focus on how the journey involved his wife, Helen, their eight children and now their thirty-one grandchildren and eight great grandchildren. The future of the Chavez Legacy is in their hands and I know they are all eager and ready for the challenges. Legacy of Cesar Chavez For Latinos and other poor people in the United States the journey to acceptance, understanding, and justice has been long and difficult. We all know the stories and challenges. One man among Mexican, Central, and Southern American descendents reached the pinnacle of American history. Cesar Chavez, who died in 1993, taught many to overcome the fear to succeed and gained worldwide fame for his achievements for farm workers and other underrepresented workers. Small in stature, dark skinned with a fierce drive for justice Chavez’s life inspired several generations and continues to inspire new immigrants to live in dignity and without fear as we claim our place in society and history. -

United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero

United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero PHOTO: EL MALCRIADO STAFF Photo: Jerry Whipple (center), regional director for UAW Region 6, presents a $100,000 check to the UFW executive board at a ceremony in Los Angeles in 1974. From left to right: Marshall Ganz, Eliseo Medina, Pete Velasco, Mack Lyons, Jerry Whipple, Richard Chavez, Cesar Chavez, Gil Padilla, Phillip Vera Cruz, Dolores Huerta. United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero Workers For Justice Today 23 United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero Kent Wong What I learned from Philip Vera Cruz first met Philip Vera Cruz when I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley in the early 1970s. I remember thinking how out of place Philip looked on campus. He wore old Iwork clothes, a sweater vest, and a crumpled brown hat. His hair was gray and his face lined from the years he had worked in the fields of California under the relentless sun. Philip had come to UC Berkeley to speak before an Asian American Studies class. When he opened his mouth to speak, the students were in for a surprise. Despite the quiet demeanor usually associated with older Asian immi- grants, Philip spoke with great force and passion. Philip was a vice president of the United Farm Workers Union, the highest-ranking Filipino in the union. advancing justice-la.org 2 aasc.ucla.edu Untold Civil Rights Stories: Asian Americans Speak Out for Justice United Farm Workers (UFW) Movement: Philip Vera Cruz, Unsung Hero 24 Untold Civil Rights Stories “My life within the union, my life now outside the union, are all one: my continual struggle to improve my life and the lives of my fellow workers. -

Forty Acres: Cesar Chavez and the Farm Workers

Forty Acres Cesar Chavez and the Farm Workers Mark Day INTRODUCTION BY CESAR CHAVEZ PRAEGER PUBLISHERS NEW YORK –WASHINGTON –LONDON Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the staff and parishioners of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Delano, to Fathers Al Peck, Ed Fronake, Ignatius DeGroot, Dave Duran, and Tom Messner, and to Ray Reyes and Lala Granillo for their many kindnesses. I am also indebted to the staff of El Maleriado—Doug Adair, Marcia Sanchez, Ben Madocks, and Richard Ibarra. My special thanks to Andy Zermeno, a sensitive man and a talented artist. I also owe thanks to: Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker for permission to adapt for us in this book my first article, “A Steak Dinner or a Plate of Beans?”; Bob Hoyt, editor of The National Catholic Reporter, for permission to use material from my article “The Grape Boycott: Where Is It Now?” (copyright April 24, 2970, The National Catholic Reporter); Clay Barbeau, editor of Way Magazine, for permission to adapt :”The Black Eagle and the Grapes of the Desert”; the Delano Historical Society; Ken Blum; writer Jacques Levy; five diligent journalists: Ron Taylor, of the Fresno Bee, Bill Acres, formerly of the Delano Record, Helen Manning and Eric Brazil of the Salinas Californian, and Sam Kushner, of the People’s World; Bob Thurber, Gene Daniels, Stanley Randal, George Ballis, Chris Sanchez, Bob Fitch, and Gerald Sherry, editor of the Central California Register, for their memorable photographs; the Fresno Bee; the Delano Record; and Juan A. Cuauhtemoc for his poem “Ese Chuy, Jesus,” from Poesias de la Causa.