HATUTAN Midline Evaluation June 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book 5 Development Partners

República Democrática de Timor-Leste State Budget 2017 Approved Development Partners Book 5 “Be a Good Citizen. Be a New Hero to our Nation” Table of Contents Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Part 1: Development Assistance in Combined Sources Budget 2017 ..................... 4 Part 2: National Development Plans .................................................................................. 4 2.1 Strategic Development Plan 20112030 .............................................................................. 4 2.1 Program of the 6th Constitutional Government 20152017 ......................................... 5 2.3 The New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States ............................................................... 6 2.3.1 SDG and SDP Harmonization ........................................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Timor‐Leste’s Second Fragility Assessment ............................................................................. 8 Part 3: Improved Development Partnership ............................................................... 10 3.1 Development Partnership Management Unit ................................................................. 10 3.2 Aid Transparency Portal (ATP) ........................................................................................... 10 Part 4: Trend of Development Assistance to TimorLeste ..................................... -

WFP Timor-Leste Country Brief February 2019 Government of Timor-Leste, SRAC/Multilateral Contributions, Private Donors

WFP Timor-Leste In Numbers Country Brief 1.3 mt of ready-to-use supplementary food February 2019 distributed to 532 girls and boys under five 7.7 mt of Super Cereal distributed to 1,796 pregnant and nursing women 14 nutrition education sessions organised in five municipalities, reaching 960 community members US$ 2.08 m six months (March - August 2019) net funding requirements 89% 11% 2,328 people assisted in February 2019 Operational Context Operational Updates Timor-Leste is one of the world’s newest countries, being Thanks to the coordination efforts by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (MoFA) a meeting was organized on internationally recognized as an independent state in 2002. 26 February with representatives from key line Ministries to Poverty rates have dropped from 49.9 percent in 2007 to discuss the upcoming signature of the Letter of 41.8 percent in 2014 according to the World Bank. Understanding (LoU) between MoFA and WFP for the CSP According to the first Integrated Food Security Phase implementation. Classification (IPC) Analysis Report released in January The results of a joint Ministry of Health-WFP Social 2019, approximately 430,000 people (36 percent) are Behaviour Change Communication (SBCC) partner mapping chronically food insecure, out of which 15 percent is survey questionnaire are being consolidated to identify who experiencing severe chronic food insecurity (IPC Level 4). is working in which SBCC intervention. The major contributing factors are low agricultural WFP and Australian programme TOMAK are developing productivity, poor quality and quantity of food communication materials including a series of posters for consumption, and low value livelihood strategies combined adolescents and a special edition on Adolescents on Lafaek with high dependency on single livelihoods. -

República Democrática De Timor-Leste

República Democrática de Timor-Leste Book 3A CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1. Background of the Infrastructure Fund ............................................................................. 4 1.2. Regulation framework of the Infrastructure Fund............................................................. 6 1.3. IF management and institutional arrangements ............................................................... 7 1.4. IF standards, tools and procedures .................................................................................... 8 1.4.1. Feasibility Study .............................................................................................................. 9 1.4.2. Project Appraisal ............................................................................................................. 9 1.4.3. Ex‐Post Evaluation ........................................................................................................ 10 1.4.4. GIS Database ................................................................................................................. 10 1.5. IF Budget allocation and expenditures ............................................................................ 11 1.6. Results of the IF projects implementation during 2011‐2020 ......................................... 12 2. PORTFOLIO OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE FUND ............................................................................ -

Dili to Baucau Highway Project

Updated Corrective Action Plan Project Number: 50211-001 May 2018 TIM: Dili to Baucau Highway Project Prepared by Ministry of Development and Institutional Reform for the Asian Development Bank. The Updated Corrective Action Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country programme or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Ministry of Development and of Institutional Reform Dili to Baucau Highway Project CORRECTIVE ACTION PLAN (CAP) Completion Report Package A01-02 (Manatuto-Baucau) May 2018 Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Corrective Action Plan (CAP) Ministry of Development and of Institutional Reform Completion Report Dili to Baucau Highway Project Table of Contents List of Tables ii List of Figures iii Acronyms iv List of Appendices v 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Methodology 2 2 THE PROJECT 3 2.1 Overview of the Project 3 2.2 Project Location 3 3 LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK 5 3.1 Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement 5 3.2 Definition of Terms Use in this Report 5 4 RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK 0 5 THE RAP PROCESS 0 5.1 RAP Preparation 0 5.1.1 RAP of 2013 0 5.1.2 RAP Validation in 2015 0 5.1.3 Revalidation -

A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste

2019 A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste 2018: A A Journal Journal of Changeof Change in Timor-Leste in Timor-Leste 2019 A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste 2018: A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste is an annual publication of UNICEF Timor-Leste. Data in this report are drawn from the most recent available statistics from UNICEF and other United Nations agencies, and the Government of Timor-Leste. Cover photograph: © UNICEF Timor-Leste/2019/BSoares Girls take part in the ‘Kick for Identity’ junior football match to promote birth registration in Timor-Leste. © UNICEF Timor-Leste/2019/Helin THREE DECADES OF CHILD RIGHTS This has been a significant year for Timor-Leste. The 30th of August 2019 marked 20 years since the Popular Consultation, the countrywide vote that eventually led to the restoration of the country’s independence in 2002. The two decades that followed this momentous day have had their challenges, but have seen Timor- Leste achieve many milestones. The proportion of Timorese living in poverty reduced from 50 per cent in 2007 to 42 per cent in 2014. However, 49 per cent of children between the ages of 0 and 14 live below the national poverty line as of 2014. Undoubtedly, there is much work that still needs to be done. Towards this goal, UNICEF has worked closely with the Government of Timor- Leste, partners and donors to accelerate progress for children in the country: through the provision of technical and policy advice; advocacy; and supporting modeling initiatives or larger nationwide actions that draw attention to issues children face, drive change, and support actions that can catalyze progress. -

National Coastal Vulnerability Assessment and Designing of Integrated Coastal Management and Adaptation Strategic Plan for Timor-Leste

National Coastal Vulnerability Assessment and Designing of Integrated Coastal Management and Adaptation Strategic Plan for Timor-Leste Coastal Vulnerability Assessment Report February 2018 © UNDP 2018 The report is contracted by United Nations Development Programme, UNDP and Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, MAF and prepared by Global CAD, 2018. The Copyright of the report is the property of UNDP and the Government of Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, 2018 1-2 List of Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank AL-GIS Agriculture and Land Use Geographic Information System ATSEA Arafura and Timor Seas Ecosystem Action AUSAID Australian Agency for International Development CC Climate Change CCCBTL Centre for Climate Change and Biodiversity Timor-Leste CBA Cost Benefit Analysis CEA Cost-Effectiveness Analysis CHW Coastal Hazard Wheel CI Conservation International CIVAT Coastal Integrity Vulnerability Assessment Tool cm centimetres CO2 Carbon Dioxide COP Conference of Parties CTC Coral Triangle Center CVA Coastal Vulnerability Assessment CVI Coastal Vulnerability Index DED Detailed Engineering Design DEM Digital Elevation Model DRR Disaster Risk Reduction EBA Ecosystem-Based Adaptation ECMWF European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasting ENSO El Niño Southern Oscillation EU European Union EWS Early Warning System FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FGD Focus Group Discussion GDP Gross Domestic Product GIS Geographical Information System GIZ German Corporation for International Cooperation GoTL Government of Timor-Leste GPS Global -

Manatuto.Pdf

Result of Data Collection of Existing Human Resources and The Main Key Areas of Training Municipality of Manatuto Fundo do Desenvolvimento do Capital Humano (FDCH) (Human Capital Development Fund – HCDF) www.fdch.gov.tl Council of Administration of Human Capital Development Fund (CA-FDCH) Former Office of Ministry of Finance, Building #5, 2nd Floor, Government Palace, Dili, Timor-Leste Email: [email protected] FUNDO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DO CAPITAL HUMANO (FDCH) CONTENT CONTENT ............................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF TABLE ........................................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................................................................ 4 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER ............................................................................................................. 6 INTRODUCTION FROM THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY OF FDCH................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 11 PART A: INTRODUCTION, OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY .............................................................. -

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’S Office (RCO) Situation Report No

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) Situation Report No. 6 (As of 21 April 2021) This report is produced by RCO Timor-Leste in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by UN Timor-Leste. It covers the period from 16 to 21 April 2021. The next report will be issued on or around 28 April 2021. HIGHLIGHTS • Following the Government’s declaration of a state of calamity in Dili on 8 April, several humanitarian donors have provided additional humanitarian support the flood response, equivalent to nearly USD 10 million. • According to the latest official figures (21 April) from the Ministry of State Administration, which leads the Task Force for Civil Protection and Natural Disaster Management, a total of 28,734 households have reportedly been affected by the floods across all 13 municipalities. Of whom, 90% - or 25,881 households – are in Dili municipality. • The same report cites that currently there are 6,029 temporary displaced persons in 30 evacuation facilities across Dili, the worst-affected municipality. • 4,546 houses across all municipalities have reportedly been destroyed or damaged. • According to the preliminary assessment by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries conducted in 9 municipalities to date, a total of 1,820 ha of rice crops and 190 ha of maize crops have been affected by the flooding. 13 28,734 4,546 30 41 Municipalities Total affected Houses Evacuation Fatalities affected (out households destroyed or facilities in of 13 across the damaged across Dili municipalities) country the country SITUATION OVERVIEW Heavy rains across the country from 29 March to 4 April have resulted in flash floods and landslides affecting all 13 municipalities in Timor-Leste to varying degrees, with the capital Dili and the surrounding low-lying areas the worst affected. -

Adapt Innovate Deliver ATSEA-2 Annual Report 2020: Adapt

Arafura and Timor Seas Ecosystem Action ATSEA-2 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Adapt Innovate Deliver ATSEA-2 Annual Report 2020: Adapt. Innovate. Deliver This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes or to provide dissemination for public responses, provided prior written permission is obtained from the ATSEA-2 Regional Project Manager, acknowledgment of the source is made and no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. ATSEA-2 would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale, any commercial purpose or any purpose other than those given above without a written agreement between ATSEA-2 and the requesting party. Published by the Arafura and Timor Seas Ecosystem Action Phase II (ATSEA-2). Printed in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia Suggested Citation: ATSEA-2. 2021. ATSEA-2 Annual Report 2020: Adapt. Innovate. Deliver. Arafura and Timor Seas Ecosystem Action Phase II (ATSEA-2), Bali, Indonesia. 62p. The activities described in this report were made possible with the generous support from our sponsoring organizations - the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of TSEA-2A implementing partners and its participating organizations. The designation employed and the presentation do not imply expression of opinion, whatsoever on the part of ATSEA-2 concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authority or concerning the delimitation of its boundaries. ATSEA-2 Regional Project Management Unit Jl. -

Intersectoral Collaboration for People-Centred Mental Health Care in Timor-Leste, a South-East Asian Country in the Process of Strengthening Its Mental Health System

Hall et al. Int J Ment Health Syst (2019) 13:72 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0328-1 International Journal of Mental Health Systems RESEARCH Open Access Intersectoral collaboration for people-centred mental health care in Timor-Leste: a mixed-methods study using qualitative and social network analysis Teresa Hall1* , Ritsuko Kakuma2,3, Lisa Palmer4, Harry Minas3, João Martins5 and Greg Armstrong1 Abstract Background: Intersectoral collaboration is fundamental to the provision of people-centred mental health care, yet there is a dearth of research about how this strategy operates within mental health systems in low- and middle- income countries. This is problematic given the known attitudinal, structural and resource barriers to intersectoral collaboration in high-income country mental health systems. This study was conducted to investigate intersectoral collaboration for people-centred mental health care in Timor-Leste, a South-East Asian country in the process of strengthening its mental health system. Methods: This study employed a mixed-methods convergent design. Qualitative data elicited from in-depth inter- views with 85 key stakeholders and document review were complemented with quantitative social network analysis to assess understandings of, the strength and structure of intersectoral collaboration in the Timorese mental health system. Results: There was consensus among stakeholder groups that intersectoral collaboration for mental health is impor- tant in Timor-Leste. Despite resource restrictions discussed by participants, interview data and social network analysis revealed evidence of information and resource sharing among organisations working within the health and social (disability and violence support) sectors in Timor-Leste (network density 0.55 and 0.30 for information and resource sharing, respectively). -

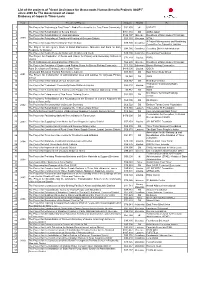

List of the Project of GGP 2000-2020

List of the projects of "Grant Assistance for Grass-roots Human Security Projects (GGP)" since 2000 by The Government of Japan Embassy of Japan in Timor-Leste Year The title of Project Amount District By 1 The Project for "Listening to East Timor" - Radio Receivers for the East Timor Community $91,850 all UNTAET 2 The Project for Rehabilitation of Becora School $151,934 Dili ADRA Japan 3 The Project for Rehabilitation of Laga Orphanage $146,107 Baucau Daughters of Mary Help of Christians 4 2000 The Project for Rebuilding of Traditional Weaving of Oecusse District $23,135 Oecusse IKTALI A Project Management and Monitoring 5 The Project for Carpentry Training for Youth in Suai $89,700 Covalima Committee for Carpentry Training The Project for Emergency Stock of Road Maintenance Materials and Fund for Early 6 $94,786 Covalima Covalima District Administration Response for Disaster 7 The Project for Build a Peaceful Nation with Children and Youth $80,200 6 districts Deo Gratias Foundation The Project for Production of Desks and Chairs for Primary and Secondary Schools in 8 $72,118 Liquica PARC Liquica 9 The Rehabilitation of Laga Orphanage (Phase II) $66,295 Baucau Daughters of Mary Help of Christians 10 The Project for Provision of Engines and Fishing Gears for Biacou Fishing Cooperative $15,192 Bobonaro Biacou Fishing Cooperative 11 Rural Development Training Center in East Timor $410,000 Liquica OISCA 12 Library and Education Training Facility Development $88,588 Dili East Timor Study Group 2001 The Project for Construction of Administration -

Infrastructure Fund Portfolio 4 1

República Democrática de Timor-Leste Infrastructure Fund Book 3A “Be a Good Cizen. Be a New Hero to our Naon” TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 I. INFRASTRUCTURE FUND PORTFOLIO 4 1. AGRICULTURE PROGRAM 5 2. WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM 5 3. URBAN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 6 4. ELECTRICITY PROGRAM 6 5. PORT PROGRAM 7 6. AIRPORT PROGRAM 7 7. MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS PROGRAM (MDG) 8 8. TASI MANE PROGRAM 8 9. EXTERNAL LOANS PROGRAM 9 10. FINANCIAL SYSTEM AND SUPPORTING INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM 9 11. INFORMATICS PROGRAM 10 12. YOUTH AND SPORTS PROGRAM 10 13. HEALTH PROGRAM 11 14. TOURISM PROGRAM 11 15. EDUCATION PROGRAM 12 16. SOCIAL SOLIDARITY PROGRAM 12 17. BRIDGES PROGRAM 12 18. SECURITY AND DEFENCE PROGRAM 13 19. ROAD PROGRAM 13 20. PUBLIC BUILDINGS PROGRAM 14 21. PREPARATION OF DESIGNS AND PROVISION OF SUPERVISION SERVICES 14 22. MAINTENANCE AND REHABILITATION PROGRAM 14 II. IF BUDGET SUMMARY 15 III. ANNEXES 17 2 | P a g e Rectification Budget Book 3A – Infrastructure Fund 2017 INTRODUCTION The infrastructure development is one of the key national priorities for strategic investment in Timor- Leste. According to the Strategic Development Plan 2011 – 2030, a central pillar of the long-term development is the building and maintenance of core and productive infrastructure that will be able to support and enhance social and economic growth that leads to a better quality of life. The main objective of the Infrastructure Fund is to support strategic projects for further growth of Timor- Leste’s economy. The Infrastructure Fund is the main governmental instrument which was established in 2011 in order to facilitate infrastructure development and provide financial sources for roads and bridges, airports and seaports, power and water supply, education and health, tourism and other major projects with budget over than $1 million which have significant impact to the country.