Interministerial Conference, Libreville, Gabon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Twenty-Sixth Session Libreville, Gabon, 4

RAF/AFCAS/19 – INFO E November 2019 AFRICAN COMMISSION ON AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS Twenty-sixth Session Libreville, Gabon, 4 – 8 November 2019 INFORMATION NOTE 1. Introduction The objective of this General Information is to provide participants at the 26th Session of AFCAS with all the necessary information so as to guide them for their travel and during their stay in Libreville, Gabon. 2. Venue and date The 26th Session of the African Commission on Agricultural Statistics (AFCAS) will be held at the Conference Room No 2 of Hôtel Boulevard – Libreville, Gabon, from 4 to 8 novembre 2019. 3. Registration Registration of participants will take place at the Front Desk of Conference Room No 2 of Hôtel Boulevard – Libreville, Gabon: AFCAS: 4 November 2019, between 08h00 and 09h00 The opening ceremony begins at 09h00. 4. Technical documents for the meetings The technical documents related to the 26th Session will be available from 30 September 2019 onwards at the following Website: http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-events/afcas/afcas26/en/ 5. Organization of the meetings The Government of the Republic of Gabon is committed to provide the required equipment for the holding of this session. You will find the list of hotels where bookings can be made for participants at the Annex 1. Transportation will be provided from the hotel to the venue for the Conference. 6. Delegations All participants are kindly requested to complete the form in Annex 2 and return it to the organizers latest by 11 October 2019. The form contains all the details required for appropriate arrangements to be made to welcome and lodge delegates (Flight numbers and schedule). -

The Case of African Cities

Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Currie, Paul, et al. "Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities." Journal of Environmental Protection 6, 9 (September 2015): 1066-1083 © 2015 Author(s) As Published 10.4236/JEP.2015.69094 Publisher Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124946 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Journal of Environmental Protection, 2015, 6, 1066-1083 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2015.69094 Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities Paul Currie1*, Ethan Lay-Sleeper2, John E. Fernández2, Jenny Kim2, Josephine Kaviti Musango3 1School of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa 2Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA 3School of Public Leadership, and the Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies (CRSES), Stellenbosch, South Africa Email: *[email protected] Received 29 July 2015; accepted 20 September 2015; published 23 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Data sourcing challenges in African nations have led many African urban infrastructure develop- ments to be implemented with minimal scientific backing to support their success. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

Djibouti: Z Z Z Z Summary Points Z Z Z Z Renewal Ofdomesticpoliticallegitimacy

briefing paper page 1 Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub David Styan Africa Programme | April 2013 | AFP BP 2013/01 Summary points zz Change in Djibouti’s economic and strategic options has been driven by four factors: the Ethiopian–Eritrean war of 1998–2000, the impact of Ethiopia’s economic transformation and growth upon trade; shifts in US strategy since 9/11, and the upsurge in piracy along the Gulf of Aden and Somali coasts. zz With the expansion of the US AFRICOM base, the reconfiguration of France’s military presence and the establishment of Japanese and other military facilities, Djibouti has become an international maritime and military laboratory where new forms of cooperation are being developed. zz Djibouti has accelerated plans for regional economic integration. Building on close ties with Ethiopia, existing port upgrades and electricity grid integration will be enhanced by the development of the northern port of Tadjourah. zz These strategic and economic shifts have yet to be matched by internal political reforms, and growth needs to be linked to strategies for job creation and a renewal of domestic political legitimacy. www.chathamhouse.org Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub page 2 Djibouti 0 25 50 km 0 10 20 30 mi Red Sea National capital District capital Ras Doumeira Town, village B Airport, airstrip a b Wadis ERITREA a l- M International boundary a n d District boundary a b Main road Railway Moussa Ali ETHIOPIA OBOCK N11 N11 To Elidar Balho Obock N14 TADJOURA N11 N14 Gulf of Aden Tadjoura N9 Galafi Lac Assal Golfe de Tadjoura N1 N9 N9 Doraleh DJIBOUTI N1 Ghoubbet Arta N9 El Kharab DJIBOUTI N9 N1 DIKHIL N5 N1 N1 ALI SABIEH N5 N5 Abhe Bad N1 (Lac Abhe) Ali Sabieh DJIBOUTI Dikhil N5 To Dire Dawa SOMALIA/ ETHIOPIA SOMALILAND Source: United Nations Department of Field Support, Cartographic Section, Djibouti Map No. -

Feuille De Route Pour La Paix Et La Reconciliation En Republique

PA-X, Peace Agreement Access Tool www.peaceagreements.org ROADMAP FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 1. Introduction anD context 1.1 THe Central African Republic Has been for several Decades engaged in serious political-military crises, calling into question the founDations of the State. Since the return to constitutional legality witH tHe election of PresiDent of tHe Republic, HeaD of State, Pr. Faustin ArcHange TOUADERA, tHe Central African Republic has resolved to seek peace, restoration of the state’s authority, justice system, economy, and general social reconstruction. 1.2 THe presence of tHe United Nations peacekeeping mission (MINUSCA), wHich took over from tHat of the African Union (MISCA), has played a very important role in the stabilization of the country, the defense of Democratic institutions, and protection of civilians. However, the armed groups have continued to spread over large areas, and in certain cases have even strengthened, thereby leading the country to a de-facto separation, wHerein there is a lack of State autHority over tHe entire national territory, as well as a real process for reconciliation in the country. 1.3 In spite of tHe volatility of tHe security situation in a large part of tHe national territory, PresiDent TOUADERA, in his desire to concretize his first priority, namely the restoration of peace throughout the country, has formulated his wise policy, extending his hand to all countries’ sons and daughters. He called on His African brotHers anD CAR frienDs to support tHe Central African people in this quest for peace. It is in response to this, anD in orDer to translate into reality the soliDarity between the Government anD tHe Central African people, tHat tHe African initiative was born. -

Reflections on Identity in Four African Cities

Reflections on Identity in Four African Cities Lome Edited by Libreville Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé Johannesburg Cape Town Simon Bekker and Anne Leildé (eds.) First published in 2006 by African Minds. www.africanminds.co.za (c) 2006 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-920051-40-6 Edited, designed and typeset by Compress www.compress.co.za Distributed by Oneworldbooks [email protected] www.oneworldbooks.com Contents Preface and acknowledgements v 1. Introduction 1 Simon Bekker Part 1: Social identity: Construction, research and analysis 2. Identity studies in Africa: Notes on theory and method 11 Charles Puttergill & Anne Leildé Part 2: Profiles of four cities 3. Cape Town and Johannesburg 25 Izak van der Merwe & Arlene Davids 4. Demographic profiles of Libreville and Lomé 45 Hugues Steve Ndinga-Koumba Binza Part 3: Space and identity 5. Space and identity: Thinking through some South African examples 53 Philippe Gervais-Lambony 6. Domestic workers, job access, and work identities in Cape Town and Johannesburg 97 Claire Bénit & Marianne Morange 7. When shacks ain’t chic! Planning for ‘difference’ in post-apartheid Cape Town 97 Steven Robins Part 4: Class, race, language and identity 8. Discourses on a changing urban environment: Reflections of middle-class white people in Johannesburg 121 Charles Puttergill 9. Class, race, and language in Cape Town and Johannesburg 145 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé 10. The importance of language identities to black residents of Cape Town and Johannesburg 171 Robert Mongwe 11. The importance of language identities in Lomé and Libreville 189 Simon Bekker & Anne Leildé Part 5: The African continent 12. -

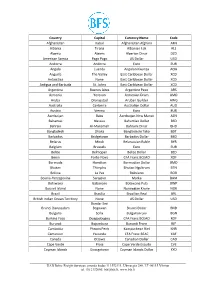

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

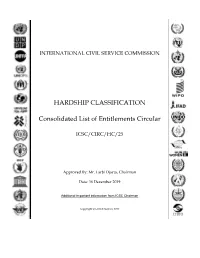

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 -

International Civil Aviation Organization Western And

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANIZATION WESTERN AND CENTRAL AFRICA OFFICE Twenty-third Meeting of the AFI Satellite Network Management Committee (SNMC/23) (Accra, Ghana, 15-19 February 2016) AFTN CIRCUIT AVAILABILITY STATISTICS FOR KANO FLIGHT INFORMATION REGION LAGOS CENTER AFTN CIRCUIT AVAILABILITY FROM JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2015. STATION ACCRA COTONOU DOUALA LIBREVILLE NIAMEY LOME MALABO MONTH % % % % % % % JAN. 2015 94.62 90.19 72.18 50.54 90.46 N/A N/A FEB. 2015 99.50 66.97 58.48 13.83 63.54 N/A N/A MAR.2015 100 100 80.60 100 97.98 N/A N/A APR. 2015 100 100 99.70 99.70 89.30 100 46.15 MAY.2015 100 100 80.60 100 98.00 100 42.00 JUN. 2015 0 100 100 93.89 98.75 100 0 JUL. 2015 100 94.7 100 100 100 100 16.10 AUG.2015 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 SEP. 2015 100 100 93.88 96.67 100 100 100 OCT. 2015 98.50 98.50 98.10 98.30 98.50 94.10 53.50 NOV.2015 100 99.6 99.6 99.6 99.6 99.6 99.6 DEC.2015 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 PLOT COMMENT ON THE STATISTICS Accra failed throughout June, 2016. This was due to faulty VSAT MODEM. Which GCAA fixed by the end of June Douala performed below ICAO recommended figure of 97% in Jan., Feb., May and Sept. Malabo circuit started operation in April 2015. Availability was below 97% in April, May, June, July and October. -

Congo-Brazzaville

CONGO-BRAZZAVILLE - The deep end of the Pool Hanlie de Beer and Richard Cornwell Africa Early Warning Programme, Institute for Security Studies Occasional Paper No 41 - September 1999 INTRODUCTION Congo-Brazzaville lies at the heart of one of Africa’s most unstable regions. To the south, Angolan conflict remains in flux between pretences of peace agreements while the war continues to rage on. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) experienced a rebel takeover, only to be constantly threatened by rebels with a further takeover. Gabon seems relatively stable, but conditions in the Central African Republic continue to boil underneath the surface. With Congo-Brazzaville in the throes of skirmishes between guerrilla fighters and a combination of government and Angolan forces, a full-blown eruption in this country will severely compromise what little peace is to be found in the entire region. Congo-Brazzaville’s history since independence in 1960, throws light on the country’s relentless woes. It has scarcely known a time when political power did not depend upon the sanction of armed force. Samuel Decalo has summed up the situation most pithily: "The complex political strife so characteristic of Congo is ... in essence a straightforward tug-of-war between ambitious elites within a praetorian environment ... power and patronage are the name of the game."1 His argument is convincing: what we have in Congo is a competition for scarce resources, made more desperate by the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) insistence on budgetary austerity and cuts in the numbers and pay of civil servants. More than half of the country’s three million people live in the towns of Brazzaville and Pointe Noire, many in shanty suburbs defined according to the ethnic and regional origins of their inhabitants. -

The Situation in the Central African Republic

ACP-EU JOINT PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ACP-EU 101.376/13/fin RESOLUTION1 on the situation in the Central African Republic The ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly, - meeting in Brussels (Belgium) from 17 to 19 June 2013, - having regard to Article 18(2) of its Rules of Procedure, - having regard to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1966 Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, - having regard to Article 3 and Protocol II of the 1949 Geneva Convention, ratified by the Central African Republic (CAR), which prohibit summary execution, rape, forced recruitment and other abuses, - having regard to the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), ratified by the CAR in 2001, as amended in Kampala in 2010, which defines the most serious international crimes, such as crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, attacks against civilian populations, torture, pillaging, sexual violence, the recruitment and use of children in armed forces and enforced disappearance, and which affirms the primary obligation of all national jurisdictions to investigate and punish, and thereby prevent, the perpetration of such crimes, - having regard to the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which has been signed by the CAR, - having regard to the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights, ratified by the CAR in 1986, - having regard to Partnership Agreement 2000/483/EC between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States of the one part, and the European Community and its Member States of the other part, signed in Cotonou (Benin) on 23 June 2000 and revised successively in 2005 and 2010, - having regard to the Libreville Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of the CAR and the Central African politico-military movements of 1 Adopted by the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly on 19 June 2013 in Brussels (Belgium).