Ukraine: Running out of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIGS Alexander PROKHANOV 氏・Alexander NAGORNY 氏 Seminar 「ロシア保守派の広島訪問と最近のロシア情勢」

CIGS Alexander PROKHANOV 氏・Alexander NAGORNY 氏 Seminar 「ロシア保守派の広島訪問と最近のロシア情勢」 Date & time: 7th August 2015 (Friday) 14:00 - 16:30 Venue: ”大会堂”(Auditorium) (2F, Nihon Kogyo Club Kaikan Bldg., 4-6 Marunouchi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo) Agenda: 14:00-14:05 Opening 14:05-14:35 Alexander Prokhanov’s lecture 「広島訪問の印象。現在の世界情勢」 (Russian with Japanese) 14:35-15:05 Alexander Nagorny’s lecture 「ロシアの情勢とウクライナをめぐる状況」 (English) 15:05-15:35 Larion Lebedev’s lecture 「福島原発事故と原子力分野における日ロ協力の道」 (Russian with Japanese) 15:35-16:30 Q&A Moderator: Daisuke Kotegawa, Research Director, CIGS Language: English・Russian Speaker's profile: ■Alexander PROKHANOV 氏(アレキサンダー・プロハーノフ氏) Born in Tbilisi. Enrolled the Moscow Aviation Institute, where he first started to write poetry and prose. Prominent writer since 1960s. Extensive experience as foreign correspondent in Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Cambodia, Angola and Ethiopia. The editor-in-chief of newspaper “Zavtra” (Tomorrow). ■Alexander NAGORNY 氏(アレキサンダー・ナゴルニー氏) Graduated post graduate course of Institute of USA and Canada in 1978 Chief analytical group, Russian Parliament, Committee of Foreign Relations Visiting Professor at University of Washington in 1991-93 Professor at Kung Hee University of Republic of Korea in 1993-95 Executive secretary general of “Izborsk Group” Deputy Editor-in-chief of “Zavtra” (Tomorrow). ■Larion LEBEDEV 氏(ラリオン・レベジェフ氏) General Director of the State Research and Development Center for Expertises of Projects and Technologies Graduated from Moscow Physical-Engineering Institute –PhD in 1984. Professor Lebedev acts as an expert of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). He actively participated in the elimination of impacts of the Chernobyl NPP accident - he worked in 1986 as the Head of Radiation Reconnaissance Group of US-605. -

Russia's Hybrid Warfare

Research Paper Research Division – NATO Defense College, Rome – No. 105 – November 2014 Russia’s Hybrid Warfare Waging War below the Radar of Traditional Collective Defence by H. Reisinger and A. Golts1 “You can’t modernize a large country with a small war” Karl Schlögel The Research Division (RD) of the NATO De- fense College provides NATO’s senior leaders with “Ukraine is not even a state!” Putin reportedly advised former US President sound and timely analyses and recommendations on current issues of particular concern for the Al- George W. Bush during the 2008 NATO Summit in Bucharest. In 2014 this liance. Papers produced by the Research Division perception became reality. Russian behaviour during the current Ukraine convey NATO’s positions to the wider audience of the international strategic community and con- crisis was based on the traditional Russian idea of a “sphere of influence” and tribute to strengthening the Transatlantic Link. a special responsibility or, stated more bluntly, the “right to interfere” with The RD’s civil and military researchers come from countries in its “near abroad”. This perspective is also implied by the equally a variety of disciplines and interests covering a 2 broad spectrum of security-related issues. They misleading term “post-Soviet space.” The successor states of the Soviet conduct research on topics which are of interest to Union are sovereign countries that have developed differently and therefore the political and military decision-making bodies of the Alliance and its member states. no longer have much in common. Some of them are members of the European Union and NATO, while others are desperately trying to achieve The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the this goal. -

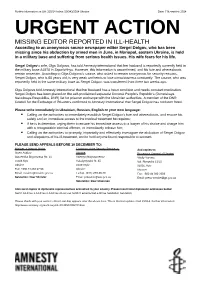

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 215/14 Index: 50/043/2014 Ukraine Date: 7 November 2014 URGENT ACTION MISSING EDITOR REPORTED IN ILL-HEALTH According to an anonymous source newspaper editor Sergei Dolgov, who has been missing since his abduction by armed men in June, in Mariupol, eastern Ukraine, is held in a military base and suffering from serious health issues. His wife fears for his life. Sergei Dolgov’s wife, Olga Dolgova, has told Amnesty international that her husband is reportedly currently held in the military base A1978 in Zaporizhhya. However, this information is unconfirmed, and his fate and whereabouts remain uncertain. According to Olga Dolgova’s source, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, Sergei Dolgov, who is 60 years old, is very weak and tends to lose consciousness constantly. The source, who was reportedly held in the same military base as Sergei Dolgov, was transferred from there two weeks ago. Olga Dolgova told Amnesty International that her husband has a heart condition and needs constant medication. Sergei Dolgov has been placed on the self-proclaimed separatist Donetsk People’s Republic‘s (Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, DNR) list for prisoner exchange with the Ukrainian authorities. A member of the DNR Council for the Exchange of Prisoners confirmed to Amnesty International that Sergei Dolgov has not been freed. Please write immediately in Ukrainian, Russian, English or your own language: . Calling on the authorities to immediately establish Sergei Dolgov’s fate and whereabouts, and ensure his safety and an immediate access to the medical treatment he requires; . If he is in detention, urging them to ensure his immediate access to a lawyer of his choice and charge him with a recognizable criminal offence, or immediately release him; . -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Ukrainian Far Right

Nations in Transit brief May 2018 Far-right Extremism as a Threat to Ukrainian Democracy Vyacheslav Likhachev Kyiv-based expert on right-wing groups in Ukraine and Russia Photo by Aleksandr Volchanskiy • Far-right political forces present a real threat to the democratic development of Ukrainian society. This brief seeks to provide an overview of the nature and extent of their activities, without overstating the threat they pose. To this end, the brief differentiates between radical groups, which by and large ex- press their ideas through peaceful participation in democratic processes, and extremist groups, which use physical violence as a means to influence society. • For the first 20 years of Ukrainian independence, far-right groups had been undisputedly marginal elements in society. But over the last few years, the situation has changed. After Ukraine’s 2014 Euro- maidan Revolution and Russia’s subsequent aggression, extreme nationalist views and groups, along with their preachers and propagandists, have been granted significant legitimacy by the wider society. • Nevertheless, current polling data indicates that the far right has no real chance of being elected in the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections in 2019. Similarly, despite the fact that several of these groups have real life combat experience, paramilitary structures, and even access to arms, they are not ready or able to challenge the state. • Extremist groups are, however, aggressively trying to impose their agenda on Ukrainian society, in- cluding by using force against those with opposite political and cultural views. They are a real physical threat to left-wing, feminist, liberal, and LGBT activists, human rights defenders, as well as ethnic and religious minorities. -

Urgent Action

UA: 297/14 Index: EUR 50/045/2014 Ukraine Date: 24 November 2014 URGENT ACTION ESTABLISH WHEREABOUTS OF DISAPPEARED MAN Aleksandr Minchenok, a 31-year-old civilian man from Lisichansk, disappeared on 21 July after being “arrested” by pro-Kyiv forces while travelling with his grandmother in eastern Ukraine. His parents, who have not heard from him since July, fear for his life. On the morning of 21 July Aleksandr Minchenok was traveling in his car with his grandmother Maria Naumova from Lisichansk, a town in Luhansk Region, to Kharkiv. He called his parents to tell them that they had passed the checkpoints controlled by pro-Russian separatist near Severodonetsk. After about 30 minutes, an unknown person who did not identify himself called Aleksandr Minchenok’s parents and told them that their son had been arrested and was being taken to the Prosecutor’s office. After this phone call, neither Aleksandr Minchenok nor the unknown caller could be reached again. Ekaterina Naumova and Yuriy Naumov, Aleksandr Minchenok’s parents, rushed to their son’s last known location and found people who told them that their son had been apprehended by the territorial defence battalion Aidar, one of over thirty so-called volunteer battalions to have emerged as part of the pro-Kyiv forces in the wake of the conflict. Members of the pro-Kyiv forces present at the site told the parents that Aleksandr Minchenok had already been released near Starobelsk, a town a short distance from Luhansk. Aleksandr Minchenok’s grandmother said that they had been stopped by men in military uniforms, but she could not remember what insignia they had. -

The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(S): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(s): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No. 179 (May, 2003), pp. 197-234 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600827 . Accessed: 05/01/2014 17:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.110.33.183 on Sun, 5 Jan 2014 17:29:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE CAUSES OF UKRAINIAN-POLISH ETHNIC CLEANSING 1943* Ethniccleansing hides in the shadow of the Holocaust. Even as horrorof Hitler'sFinal Solution motivates the study of other massatrocities, the totality of its exterminatory intention limits thevalue of the comparisons it elicits.Other policies of mass nationalviolence - the Turkish'massacre' of Armenians beginningin 1915, the Greco-Turkish'exchanges' of 1923, Stalin'sdeportation of nine Soviet nations beginning in 1935, Hitler'sexpulsion of Poles and Jewsfrom his enlargedReich after1939, and the forcedflight of Germans fromeastern Europein 1945 - havebeen retrievedfrom the margins of mili- tary and diplomatichistory. -

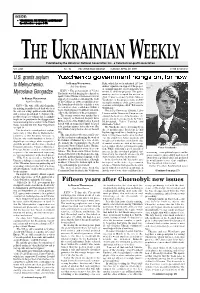

Yuschenko Government Hangs On, For

INSIDE: • “CHORNOBYL: THE FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY” Special section — pages 4-10. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX No. 16 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 22, 2001 $1/$2 in Ukraine HE YuschenkoKRAINIAN government hangsEEKLY on, for now U.S.T grants asylum U W by Roman Woronowycz Rada, which last week submitted 237 law- Kyiv Press Bureau makers’ signatures in support of the propos- to Melnychenko, al. A simple majority of 226 signatures was KYIV – The government of Victor needed to table the proposal. The parlia- Yuschenko was left hanging by a thread on mentary session accepted the motion on Myroslava Gongadze April 19 after Ukraine’s Parliament voted in April 17 prior to a report by Prime Minister by Roman Woronowycz support of a resolution criticizing the work Yuschenko on the progress made in 2000 Kyiv Press Bureau of his Cabinet in 2000 as unsatisfactory. on implementation of the government’s The lawmakers decided to schedule a vote KYIV – The wife of Heorhii Gongadze, economic revival plan, called “Reforms for on a motion of no confidence within a the missing journalist feared dead who is at Well-Being.” week, which if passed would lead automati- the center of a huge political crisis in Kyiv, The Social Democrats (United), Labor and a former presidential bodyguard who cally to the dissolution of the government. Ukraine and the Democratic Union are con- produced tape recordings that seemingly The stormy session was marked by a sidered the bastions of the business oli- implicate the president in the disappearance near tragedy as National Deputy Lilia garchs and are led respectively, by Viktor have received political asylum in the United Hryhorovych of the Rukh faction doused Medvedchuk, Viktor Pinchuk and States, revealed the U.S. -

Biden and Ukraine: a Strategy for the New Administration

Atlantic Council EURASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Biden and Ukraine: A Strategy for the New Administration ANDERS ÅSLUND, MELINDA HARING, WILLIAM B. TAYLOR, MARCH 2021 JOHN E. HERBST, DANIEL FRIED, AND ALEXANDER VERSHBOW Introduction US President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., knows Ukraine well. His victory was well- received in Kyiv. Many in Kyiv see the next four years as an opportunity to reestablish trust between the United States and Ukraine and push Ukraine’s reform aspirations forward while ending Russia’s destabilization of Ukraine’s east. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is greatly interested in reestablishing a close US-Ukraine relationship, which has gone through a bumpy period under former US President Donald J. Trump when Ukraine became a flash point in US domestic politics. Resetting relations with Kyiv will not be simple. As vice president, Biden oversaw Ukraine policy, visited the country six times, and knows most of its players and personalities, which is an obvious advantage. But Zelenskyy is different from his immediate predecessor. He hails from Ukraine’s Russian- speaking east, was not an active participant in the Revolution of Dignity, has had little contact with the West, and took a battering during Trump’s first impeachment in which Ukraine was front and center. However, Zelenskyy is keen to engage with the new Biden team and seeks recognition as a global leader. The Biden administration would be wise to seize this opportunity. The first priority for the new Biden team should be to get to know the players in Ukraine and Zelenskyy’s inner circle (Zelenskyy’s team and his ministers are not household names in Washington) and to establish a relationship of trust after the turbulence of the Trump years. -

Olena Semenyaka, the “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism

Olena Semenyaka, The “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism Adrien Nonjon Illiberalism Studies Program Working Papers, September 2020 For years, Ukrainian nationalist movements such as Svoboda or Pravyi Sektor were promoting an introverted, state-centered nationalism inherited from the early 1930s’ Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (Orhanizatsiia Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv) and largely dominated by Western Ukrainian and Galician nationalist worldviews. The EuroMaidan revolution, Crimea’s annexation by Russia, and the war in Donbas changed the paradigm of Ukrainian nationalism, giving birth to the Azov movement. The Azov National Corps (Natsional’nyj korpus), led by Andriy Biletsky, was created on October 16, 2014, on the basis of the Azov regiment, now integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard. The Azov National Corps is now a nationalist party claiming around 10,000 members and deployed in Ukrainian society through various initiatives, such as patriotic training camps for children (Azovets) and militia groups (Natsional’ny druzhiny). Azov can be described as a neo- nationalism, in tune with current European far-right transformations: it refuses to be locked into old- fashioned myths obsessed with a colonial relationship to Russia, and it sees itself as outward-looking in that its intellectual framework goes beyond Ukraine’s territory, deliberately engaging pan- European strategies. Olena Semenyaka (b. 1987) is the female figurehead of the Azov movement: she has been the international secretary of the National Corps since 2018 (and de facto leader since the party’s very foundation in 2016) while leading the publishing house and metapolitical club Plomin (Flame). Gaining in visibility as the Azov regiment transformed into a multifaceted movement, Semenyaka has become a major nationalist theorist in Ukraine. -

The Kremlin's Irregular Army: Ukrainian Separatist Order of Battle

THE KREMLIN’S IRREGULARY ARMY: UKRAINIAN SEPARATIST ORDER OF BATTLE | FRANKLIN HOLCOMB | AUGUST 2017 Franklin Holcomb September 2017 RUSSIA AND UKRAINE SECURITY REPORT 3 THE KREMLIN’S IRREGULAR ARMY: UKRAINIAN SEPARATIST ORDER OF BATTLE WWW.UNDERSTANDINGWAR.ORG 1 Cover: A Pro-Russian separatist sits at his position at Savur-Mohyla, a hill east of the city of Donetsk, August 28, 2014. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing or from the publisher. ©2017 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2017 in the United States of America by the Instittue for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 understandingwar.org 2 Franklin Holcomb The Kremlin’s Irregular Army: Ukrainian Separatist Order of Battle ABOUT THE AUTHOR Franklin Holcomb is a Russia and Ukraine Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War where he focuses on the war in Ukraine, Ukrainian politics, and Russian foreign policy in Eastern Europe. His current research focuses on studying the development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Russian-backed separatist formations operating in Eastern Ukraine, as well as analyzing Russian political and military activity in Moldova, the Baltic, and the Balkans. Mr. Holcomb is the author of “The Order of Battle of the Ukrainian Armed Forces: A Key Component in European Security,” “Moldova Update: Kremlin Will Likely Seek to Realign Chisinau”, “Ukraine Update: Russia’s Aggressive Subversion of Ukraine,” as well as ISW’s other monthly updates on the political and military situation in Ukraine. -

Managed Nationalism: Contemporary Russian Nationalistic Movements

88 FIIA Working Paper August 2015 Veera Laine MANAGED NATIONALISM CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAN NATIONALISTIC MOVEMENTS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO THE GOVERNMENT Veera Laine Research Fellow The Finnish Institute of International Affairs The Finnish Institute of International Affairs Kruunuvuorenkatu 4 FI-00160 Helsinki tel. +358 9 432 7000 fax. +358 9 432 7799 www.fiia.fi ISBN: 978-951-769-460-5 ISSN: 2242-0444 Language editing: Lynn Nikkanen The Finnish Institute of International Affairs is an independent research institute that produces high-level research to support political decision-making and public debate both nationally and internationally. All manuscripts are reviewed by at least two other experts in the field to ensure the high quality of the publications. In addition, publications undergo professional language checking and editing. The responsibility for the views expressed ultimately rests with the authors. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Research design and data used 6 1.2 Concepts and structure of the paper 9 2 THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS 12 2.1 The Eurasian Youth Union and the Russian March as examples of nationalism 15 2.2 The example movements’ ideas as presented today 18 2.3 EuroMaidan, Crimea, and “Novorossiya” 21 2.4 General notes on the Internet presence 23 2.5 The ideological basis of the movements 23 3 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE STATE AND THE NATIONALISTS 25 3.1 Electoral protests 2011–2012 – the “Bolotnaya case” 25 3.2 Ethnic riots in Moscow in 2013 – the “Biryulevo case” 27 3.3 Russian Marches in Moscow in 2014 29 3.4 “Antimaidan” and the Russian Spring 32 4 CONCLUSIONS: MANAGED NATIONALISM – HOW IS IT ACHIEVED? 35 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 3 SUMMARY This paper argues that nationalist movements in Russia can have a certain role to play in the Kremlin’s management of nationalism in the country, despite the fact that they might promote a very different form of nationalism than the state leadership itself.