Frontier in Transition : a History of Southwestern Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Section 1

COLORADO FLOODPLAIN AND STORMWATER CRITERIA MANUAL CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION 1 PURPOSE CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION 1 PURPOSE JANUARY 6, 2006 PURPOSE CH1-100 COLORADO FLOODPLAIN AND STORMWATER CRITERIA MANUAL CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION 1 PURPOSE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1 TITLE ............................................................................................................... CH1-102 1.2 PURPOSE ....................................................................................................... CH1-102 1.3 JURISDICTION................................................................................................CH1-103 1.3.1 VARIANCE PROCEDURES............................................................... CH1-103 CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION 1 PURPOSE JANUARY 6, 2006 PURPOSE CH1-101 COLORADO FLOODPLAIN AND STORMWATER CRITERIA MANUAL CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION 1 PURPOSE 1.1 TITLE The criteria and design standards presented herein together with all future amendments and revisions shall be known as the "COLORADO FLOODPLAIN AND STORMWATER CRITERIA MANUAL" (hereafter referred to as Statewide Manual or Manual). 1.2 PURPOSE The overall Manual contents have been prepared and organized into two volumes. Volume I of the Manual contains information and guidelines that are necessary for floodplain and stormwater management practices. Volume II contains guidelines and procedures for floodplain and stormwater engineering analyses and design. The criteria presented in Volume I of the Manual -

Origin and Classification of Mango Varieties in Hawaii

ORIGIN AND CLASSIFICATION OF MANGO VARIETIES IN HAWAII R. A. Hamilton Emeritus Professor, Department of Horticulture College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources University of Hawaii at Manoa Mangos (Mangifera indica) are widely grown of polyembronic mango that became popular in as a home garden fruit in the warmer, drier areas Hawaii was the "Chinese" mango (,No.9'), of all major islands of Hawaii. The fruit is mostly originally from the West Indies, but so called consumed fresh as a breakfast or dessert fruit. because it was frequently grown by persons of Small quantities are also processed into mango Chinese ancestry. Indian mangos are mostly seed preserves, pickles, chutney, and sauce. mono embryonic types originating on the Indian subcontinent, a center of mango diversity. Many Production monoembryonic mango cuitivars have been Most mangos in Hawaii are grown in introduced to Hawaii as a result of their dooryards and home gardens. Although introduction and selection in Florida, an important commercial production has been attempted, center of mango growing in the Americas. Finally, acreages remain small. Production from year to several cuitivars, mostly seedlings of mono year tends to be erratic, which has resulted in embryonic cuitivars, have been selected and limited commercial success. Shipment to the U.S. named in Hawaii (Tables 1 and 2). mainland is presently prohibited due to the presence in Hawaii of tephritid fruit flies and the Cultivar Introduction and Selection mango weevil, Cryptorhynchus mangiferae, which is The exact date of the first introduction of not found in other mango-growing areas of the mangos into Hawaii is not known. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 - 1890 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h33n2hw Author Luckett, Matthew S Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Matthew S Luckett 2014 © Copyright by Matthew S Luckett 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 by Matthew S Luckett Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Stephen A. Aron, Chair This dissertation explores the social, cultural, and economic history of horse stealing among both American Indians and Euro Americans in Lincoln County, Nebraska from 1860 to 1890. It shows how American Indians and Euro-Americans stole from one another during the Plains Indian Wars and explains how a culture of theft prevailed throughout the region until the late-1870s. But as homesteaders flooded into Lincoln County during the 1870s and 1880s, they demanded that the state help protect their private property. These demands encouraged state building efforts in the region, which in turn drove horse stealing – and the thieves themselves – underground. However, when newspapers and local leaders questioned the efficacy of these efforts, citizens took extralegal steps to secure private property and augment, or subvert, the law. -

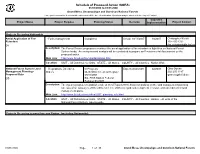

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2008 to 03/31/2008 Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management Completed Actual: 10/11/2007 10/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 202-205-1332 EA [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. National Forest System Land - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:02/2008 02/2008 Gina Owens Management Planning - Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-205-1187 Proposed Rule 08/31/2007 [email protected] EIS Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 01/2008 Description: The Agency proposes to publish a rule at 36 CFR part 219 to finish rulemaking on the land management planning rule issued on January 5, 2005 (2005 rule). The 2005 rule guides development, revision, and amendment of land management plans. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/emc/nfma/2007_planning_rule.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All -

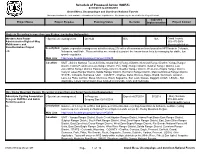

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Western Area Power - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A David Loomis Administration Right-of-Way 303-275-5008 Maintenance and [email protected] Reauthorization Project Description: Update vegetation management activities along 278 miles of transmission lines located on NFS lands in Colorado, EIS Nebraska, and Utah. These activities are intended to protect the transmission lines by managing for stable, low growth vegetation. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=30630 Location: UNIT - Ashley National Forest All Units, Grand Valley Ranger District, Norwood Ranger District, Yampa Ranger District, Hahns Peak/Bears Ears Ranger District, Pine Ridge Ranger District, Sulphur Ranger District, East Zone/Dillon Ranger District, Paonia Ranger District, Boulder Ranger District, West Zone/Sopris Ranger District, Canyon Lakes Ranger District, Salida Ranger District, Gunnison Ranger District, Mancos/Dolores Ranger District. STATE - Colorado, Nebraska, Utah. COUNTY - Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Eagle, Grand, Gunnison, Jackson, Lake, La Plata, Larimer, Mesa, Montrose, Routt, Saguache, San Juan, Dawes, Daggett, Uintah. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Linear -

Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © 1

MAGO PRODUCTIO I PAKISTA BY M. H. PAHWAR Published by: M. H. Panhwar Trust 157-C Unit No. 2 Latifabad, Hyderabad Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 Chapter No Description 1. Mango (Magnifera Indica) Origin and Spread of Mango. 4 2. Botany. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 3. Climate .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 4. Suitability of Climate of Sindh for Raising Mango Fruit Crop. 25 5. Soils for Commercial Production of Mango .. .. 28 6. Mango Varieties or Cultivars .. .. .. .. 30 7. Breeding of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 52 8. How Extend Mango Season From 1 st May To 15 th September in Shortest Possible Time .. .. .. .. .. 58 9. Propagation. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 61 10. Field Mango Spacing. .. .. .. .. .. 69 11. Field Planting of Mango Seedlings or Grafted Plant .. 73 12. Macronutrients in Mango Production .. .. .. 75 13. Micro-Nutrient in Mango Production .. .. .. 85 14. Foliar Feeding of Nutrients to Mango .. .. .. 92 15. Foliar Feed to Mango, Based on Past 10 Years Experience by Authors’. .. .. .. .. .. 100 16. Growth Regulators and Mango .. .. .. .. 103 17. Irrigation of Mango. .. .. .. .. .. 109 18. Flowering how it takes Place and Flowering Models. .. 118 19. Biennially In Mango .. .. .. .. .. 121 20. How to Change Biennially In Mango .. .. .. 126 Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 21. Causes of Fruit Drop .. .. .. .. .. 131 22. Wind Breaks .. .. .. .. .. .. 135 23. Training of Tree and Pruning for Maximum Health and Production .. .. .. .. .. 138 24. Weed Control .. .. .. .. .. .. 148 25. Mulching .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 150 26. Bagging of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 156 27. Harvesting .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 157 28. Yield .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 163 29. Packing of Mango for Market. .. .. .. .. 167 30. Post Harvest Treatments to Mango .. .. .. .. 171 31. Mango Diseases. .. .. .. .. .. .. 186 32. Insects Pests of Mango and their Control . -

THREE SACRED VALLEYS): an Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S

Paitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (THREE SACRED VALLEYS): An Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S. Air Force Electronic Combat Test Capability Actions and Alternatives at the Utah Test and Training Range Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David; Olmsted, John Publisher Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Download date 01/10/2021 12:00:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/271235 PAITU NANASUAGAINDU PAHONUPI(THREE SACRED VALLEYS): AN ASSESSMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL RESOURCES POTENTIALLY AFFECTED BY PROPOSED U.S. AIR FORCE ELECTRONIC COMBAT TEST CAPABILITY ACTIONS AND ALTERNATIVES AT THE UTAH TEST AND TRAINING RANGE DRAFT INTERIM REPORT By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo John E. Olmsted Institute for Social Research University of Michigan April 14, 1989 Submitted to: Science Applications International Corporation Las Vegas, Nevada TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Description of Study Area 2 Description of Project 2 Site Specific Assessment 3 Tactical Threat Area 3 Threat Sites and Array 4 Range Maintenance Facilities 4 Programmatic Assessment 5 Airspace and Flight Activities Effects 5 Gapfiller Radar Site 5 Future Programmatic Assessments 5 Commercial Power 5 Fiber -optic Communications Network 5 Project - Related Structures and Activities on DOD lands 5 CHAPTER TWO ETHNOHISTORY OF INVOLVED NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS 7 Ethnic Groups and Territories 7 Overview 7 Gosiutes 9 Pahvants 12 Utes 13 Early Contact, Euroamerican Colonization, -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018 Designated in the original Wilderness Act of 1964, the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness covers more than 183,000 acres spanning the Gunnison and White River National Forests. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

"Simulations of Paradox Salt Basin."

&>.; -A , - f %' . _ / I SIMULATIONS OF PARADOX SALT BASIN Ellen J. Quinn and Peter M. Ornstein 8402060151 620824 PDR WASTE WM-16PD 3104.1/EJQ/82/08/09/0 - 1 - Purpose This report documents the preliminary NRC in-house modeling of a bedded salt site. The exercise has several purposes: 1) to prepare for receipt of the site characterization report by analyzing one of the potential salt sites; 2) to gain experience using the salt related options of the SWIFT code; and 3) to determine the information and level of detail necessary to realistically model the site. Background The Department of Energy is currently investigating several salt deposits as potential repository horizons. The sites include both salt beds and salt domes located in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Utah. Site investigations will be occuring in all locations until receipt of the Site Characterization Report. In order to narrow the scope of this preliminary modeling effort, the staff decided to focus their analysis on the Paradox Basin. The site was chosen principally because of the level of information available about the site. At the time this work began, two reports on the Paradox had just been received by NRC: Permianland: A Field Symposium Guidebook of the Four Corners Geological Society (D. L. Baars, 1979), and Geology of the 3104.1/EJQ/82/08/09/0 - 2 - Paradox Basin, Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists (DL Wiegand, 1981). This in conjunction with the data information from topographic map of Paradox area (USGS Topographic Maps) and the Geosciences Data Base Handbook (Isherwood, 1981) provided the base data necessary for the modeling exercise. -

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Oklahoma Academic Standards for Social Studies, OSDE)

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Oklahoma Academic Standards for Social Studies, OSDE) Tribe:_____Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, Oklahoma_____________ Tribal website(s): http://www.c-a-tribes.org/________________________ 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” The Cheyenne and Arapaho people formed an alliance together around 1811 which helped them expand their territories and strengthen their presence on the plains. Like the Cheyenne, the Arapaho language is part of the Algonquian group, although the two languages are not mutually intelligible. The Arapaho remained strong allies with the Cheyenne and helped them fight alongside the Sioux during Red Cloud's War and the Great Sioux War of 1876, also known commonly as the Black Hills War. On the southern plains the Arapaho and Cheyenne allied with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache to fight invading settlers and U.S. soldiers. The Arapaho were present with the Cheyenne at the Sand Creek Massacre when a peaceful encampment of mostly women, children, and the elderly were attacked and massacred by US soldiers. -

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture by James Sandy, M.A. A Dissertation In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTORATE IN PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Dr. Aliza Wong Mark Sheridan, PhD. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James A. Sandy, May 2016 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way from raw idea to thesis to completed dissertation. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my career. Dr. Aliza Wong expanded my mind and horizons during a summer session course on Cultural Theory, which inspired a great deal of the theoretical framework of this work. As a co-chair of my committee, Dr. Barton Myers pushed both the project and myself further and harder than anyone else. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength and defining characteristic. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone, and for always providing the firmest yet most encouraging feedback.