Graphika Report Inauthentic Rep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bride^ of G^Arfes JK, : • First Presbyterian Church Was The, Setting Saturday Evening 'For ••

• I " II..No 49, ••:.;] ^^jy^ TEN GENTS •A."." ening s . In the true spirit of CHristmas, many local organisations and in- dividuals' have: contributed, time, effort and donations to make the. ."•'.. Finance Cbmmtssioner Wesley 'N; 3?hilio, who will become holidays brighter for less fortunate families in the township through mayor at the local governing body's, reorganization meeting on, , the annual holiday project'of the Cranford, Welfare Association. -. January 4, announced this week that there will be a, special , "Christmas for most, people is a tiniepf..happiness-and joy, but meeting of the Township^ Cpmrnittee at 8:30 p;m. on ..January . for others it could'be a id 18 to review the financial positron of Craniford and disedss occasion, were it not, for the ^gen- : !—'•' ' •'"" '; the /pireliminary budget. for erosity of our citizenry," Mrs.- Ar- : thur G. tie nnoxi executive secretary 1966.-::;:. "•:r'y-.-r: '\ '•:*••••:;•/.\'\ • of the association,, said hr ah- Wttkrs .Mayor-Elect Philo said mem- , , nouncing the niany. contributions to bers bf the public^ are invited . the Christmas project ><, >., tct^attend this^ ineeting ,and ex- >..• As a result of this generosity, press their views.' This marks the . Mrs>-JLennox reported, 44 fantilieslj first time that the public has been invited' to an open meeting for dis- ' and 121 children .are being remem-' Outgoing letter iize mail for the v hered in sonijB way this season, cussion of - the municipal budget period December 9 through Tues* prior to it* completion and pre- . •with parties, clothing, • gifts ", and day totilfed 687,079, pieces at the CHRISTMAS IN CRANFORD -~: Portion Of. -

GNB Detiene a Trocheros Que Burlan El Cerco Epidemiológico

Ultimas Preinscripción en Misión Sucre P3 Noticias GNB detiene Lunes Caracas PMV ultimasnoticiasve Año 79 Bs 30.000 N° 31.122 @UNoticias 29 @UNoticias Junio a trocheros que 2020 www.ultimasnoticias.com.ve CORONAVIRUS burlan el cerco Flexibilización a partir de hoy en 11 estados epidemiológico Ayer se confirmaron 167 casos positivos para l El protector del Táchira, Freddy Bernal, elevar a 5.297 el número de personas contagiadas. Fueron capturadas aseguró que todas las personas que sean De los casos nuevos, 39 son de transmisión sorprendidas en la frontera tratando in fraganti 39 personas de entrar a Venezuela sin pasar por los comunitaria, 22 de ellos en el Distrito Capital. P3 que intentaron ingresar controles sanitarios y epidemiológicos serán puestas a la orden del Ministerio AMISTAD desde Colombia Público. P16 Venezuela y China celebran por 46 años de relaciones El presidente Maduro ratificó su compromiso de elevar a nuevos niveles la asociación estratégica entre los dos países. P2 ASAMBLEA NACIONAL PULSO REGIONAL Equiparan cifra En Trujillo hay de diputados júbilo por 101 por lista y cumpleaños nominales P5 de Goyo P8 CORONAVIRUS La dexametasona disminuye riesgo de muerte por el virus El fármaco fue incorporado al tratamiento de los pacientes con covid-19 en Venezuela, por recomendación EFE de la Organización Mundial de la Salud. P3 ¡DETENGAN A BOLSONARO! En 60 ciudades del globo, miles de personas se unieron al llamado Día Mundial “Stop Bolsonaro”, un movimiento contra el presidente de Brasil por su irresponsabilidad en el manejo de la pandemia del coronavirus. En Brasilia, centenares de cruces fueron instaladas este domingo como homenaje a las víctimas de covid-19 en la Explanada de los Ministerios. -

Sxsw Film Festival Announces 2018 Features and Opening Night Film a Quiet Place

SXSW FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2018 FEATURES AND OPENING NIGHT FILM A QUIET PLACE Film Festival Celebrates 25th Edition Austin, Texas, January 31, 2018 – The South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals announced the features lineup and opening night film for the 25th edition of the Film Festival, running March 9-18, 2018 in Austin, Texas. The acclaimed program draws thousands of fans, filmmakers, press, and industry leaders every year to immerse themselves in the most innovative, smart and entertaining new films of the year. During the nine days of SXSW 132 features will be shown, with additional titles yet to be announced. The full lineup will include 44 films from first-time filmmakers, 86 World Premieres, 11 North American Premieres and 5 U.S. Premieres. These films were selected from 2,458 feature-length film submissions, with a total of 8,160 films submitted this year. “2018 marks the 25th edition of the SXSW Film Festival and my tenth year at the helm. As we look back on the body of work of talent discovered, careers launched and wonderful films we’ve enjoyed, we couldn’t be more excited about the future,” said Janet Pierson, Director of Film. “This year’s slate, while peppered with works from many of our alumni, remains focused on new voices, new directors and a range of films that entertain and enlighten.” “We are particularly pleased to present John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place as our Opening Night Film,” Pierson added.“Not only do we love its originality, suspense and amazing cast, we love seeing artists stretch and explore. -

Luettelo Kirjallisesta Toiminnasta Oulun Yliopistossa 2004

RAILI TOIVIO LUETTELO KIRJALLISESTA TOIM. TOIMINNASTA OULUN YLIOPISTOSSA 2004 Catalogue of publications by the staff of the University of Oulu 2004 20042003 57 K57kansi.fm Page 2 Thursday, September 22, 2005 10:26 AM OULUN YLIOPISTON KIRJASTON JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF OULU UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 57 Raili Toivio (toim.) Luettelo kirjallisesta toiminnasta Oulun yliopistossa 2004 Catalogue of publications by the staff of the University of Oulu 2004 Oulu 2005 K57kansi.fm Page 3 Thursday, September 22, 2005 10:26 AM Oulun yliopiston kirjaston julkaisuja Toimittaja/Editor Kirsti Nurkkala Copyright © 2005 Oulun yliopiston kirjasto PL 7500 90014 Oulun yliopisto Oulu University Library POB 7500 FI-90014 University of Oulu Finland ISBN 951-42-7834-8 ISSN 0357-1440 SAATAVISSA MYÖS ELEKTRONISESSA MUODOSSA ALSO AVAILABLE IN ELECTRONIC FORM ISBN 951-42-7835-6 URL: http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514278356/ OULUN YLIOPISTOPAINO Oulu 2005 Esipuhe Tähän julkaisuluetteloon on koottu tiedot Oulun yliopistossa tehdyistä opinnäytteistä ja henkilö- kunnan julkaisuista vuodelta 2004. Yhteisjulkaisut on mainittu vain kerran. Luetteloon on painettu- jen julkaisujen lisäksi otettu myös elektroniset julkaisut, atk-ohjelmat ja audiovisuaalinen aineisto, ja se sisältää myös edellisestä, vuoden 2003 luettelosta puuttuneet julkaisuviitteet. Luetteloa laadittaessa on noudatettu seuraavia periaatteita: 1. Luettelo perustuu kirjoittajien antamiin tietoihin. 2. Julkaisutiedot on järjestetty tiedekunnittain ja laitoksittain ensimmäisen yliopiston henkilökun- taan kuuluvan tekijän -

Police: Girl's Death Accidental

SPORTS Keith West returns to coaching staff at alma mater SHS FRIDAY, JUNE 7, 2019 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents B1 Police: Girl’s death accidental Gilmore was “very outdoing, surveillance video footage and the child when it was discov- Sumter department funny” and a “loving person. the initial autopsy results de- ered something was wrong, says no charges as She is the child when you’re termined the incident was the although she remained above having a bad day, she would “result of a tragic accident, water.” of now after child give you a hug.” and no charges are forthcom- McGirt said everyone who The child was unresponsive ing,” according to Tonyia Mc- was at the pool was associated drowned at hotel when she was pulled from the Girt, public information offi- or acquainted with each other. BY KAYLA ROBINS pool at the Econo Lodge on cer for the department. Initial autopsy results found [email protected] North Washington Street “Anywhere from 20 to 30 or there was no physical trauma, about 5 p.m. Saturday, accord- more children and adults and toxicology results are The aunt of the 5-year-old ing to the Sumter Police De- were in and around the pool pending. girl who died from a likely ac- partment, and transported to leading up to the incident,” “Members of the Sumter cidental drowning at a hotel Prisma Health Tuomey Hospi- McGirt said. “The video foot- Police Department are deeply PHOTO PROVIDED pool in Sumter said she miss- tal, where she later died. -

1992 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1992 Reference Index Contents: page Statistics n General in Appeals in Arguments iv Attorneys iv Briefs iv Certiorari iv Costs v Judgments, Mandates and Opinions v Original Cases v Parties vi Records vi Rules vi Stays vii Conclusion vii (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 28, 1993 In Forma Paid Original Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket 12 2,441 4,792 7,245 Cases disposed of......... 1 2,099 4,256 6,366 Remaining on docket 11 342 536 889 Cases docketed during term: Paid cases 2,062 In forma pauperis cases 4,240 Original cases...... 1 Total.. 6,303 Cases remaining from last term 942 Total cases on docket 7,245 Cases disposed of 6,366 Number remaining on docket 889 Petitions for certiorari granted: In paid cases 79 In in forma pauperis cases 14 Appeals granted: In paid cases ., 4 In in forma pauperis cases 0 Total cases granted plenary review 97 Cases argued during term 116 Number disposed of by full opinions Ill Number disposed of by per curiam opinions 4 Number set for reargument next term 0 Cases available for argument at beginning of term 66 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 4 Original cases set for argument 3 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 109 Total cases available for argument at start of next term 46 Number of written opinions of the Court 107 Per curiam opinions in argued cases 4 Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of June 28, 1993: On written motion 2,775 On oral motion 1,345 Total 4,120 Ill GENERAL: page 1991 Term closed and 1992 Term convened October 5, 1992; adjourned October 4, 1993 1 Allotment order of Justices entered 972 Bryson, William C, named Acting Solicitor General Janu- ary 20, 1993; presents Attorney General Janet Reno; re- marks by the Chief Justice 619, 865 Clinton, President, attends investiture of Justice Ginsburg 971 Court adjourned to attend Inauguration of President Clin- ton January 20, 1993 425 Court closed December 24, 1992, by order of Chief Justice Days, Drew S., Solicitor General, presented to the Court. -

May 2019 Volume Lii

201 S. Gammon Rd, Madison, WI 53717 jmmswordandshield.com “Sword & Shield” @jmmnews [email protected] MAY 2019 VOLUME LII James Madison Memorial High School Student Newspaper 5 MUST-READ THE LONG-AWAITED HUMAN RIGHTS SOCIAL JUSTICE FINAL INSTALLMENT WEEK RECAP BOOKS OF THE ASHFORDS P. 6 P. 21 P. 19 is MentalMAY Health Awareness Month 5 CELEBRITIES WHO THE INCREASING HOW YOU SHOULD HAVE STRUGGLED LINK BETWEEN SPEND YOUR WITH MENTAL HEALTH HEART DISEASE AND SUMMER BREAK DISORDERS MENTAL HEALTH P. 7 P. 17 P. 13 MAY 2019 HELLO SPARTANS, Your favorite editors-in-chief, Beatrice and Garrett, here with the the final (regular) issue of the year! We’ll save all the sappy stuff for the senior issue coming out next month, so you don’t need to grab your box of tissues quite yet. We hope you all had a great prom and good BEATRICE luck on the rest of your AP tests! We have a fan- NAUJALYTE tastic final issue for you. Our personal favorite part of the issue is the April comics. That’s right, there’s two of them this month! Also make sure to checkout our Endgame review (no spoilers!), get your questions answered by the lovely senior Megan Li, and pick out a social justice book to read over the summer. Make sure to stop and smell the May flowers! GARRETT KENNEDY STUDENT LIFE NEWS ARTS & ENTER. SPORTS OPINIONS 4 // Ask A 8 // San Diego 14 // The Perfect Date 23 // March 26 // Pros and Cons UnityPoint Health Shooting Review Madness Recap of AP Testing Professional 9 // Civil War 14 // The Act 23 // Badger 27 // The #MeToo Eating healthy during school. -

The False Promise of Adolescent Brain Science in Juvenile Justice, 85 Notre Dame Law Review

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 The alF se Promise of Adolescent Brain Science in Juvenile Justice Terry A. Maroney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Juvenile Law Commons, and the Neurology Commons Recommended Citation Terry A. Maroney, The False Promise of Adolescent Brain Science in Juvenile Justice, 85 Notre Dame Law Review. 89 (2009) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/769 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FALSE PROMISE OF ADOLESCENT BRAIN SCIENCE IN JUVENILE JUSTICE Terry A. Maroney* Recent scientific findings about the developing teen brain have both captured public attention and begun to percolate through legal theory and practice. Indeed, many believe that developmental neuroscience contributed to the U.S. Supreme Court's elimination of the juvenile death penalty in Roper v. Simmons. Post-Roper, scholars assert that the developmentally normal attributes of the teen brain counsel differential treatment of young offenders, and advocates increasingly make such arguments before the courts. The success of any theory, though, depends in large part on implementation, and challenges that emerge through implementation illuminate problematic aspects of the theory. This Article tests the legal impact of developmental neuroscience by analyzing cases in which juvenile defendants have attempted to put it into practice.It reveals that most such efforts fail. -

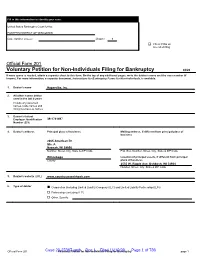

1 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 04/20 If More Space Is Needed, Attach a Separate Sheet to This Form

Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: EASTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN Case number (if known) Chapter 7 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 04/20 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and the case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name Hypervibe, Inc. 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed names, trade names and doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 39-1741497 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 2065 American Dr. Ste. A Neenah, WI 54956 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Winnebago Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business 2535 W. Ripple Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54904 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) www.countryusaoshkosh.com 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Case 20-27367-gmhVoluntary Petition for Non-IndividualsDoc 1 Filed Filing 11/10/20 for Bankruptcy Page 1 of 736 page 1 Debtor Hypervibe, Inc. Case number (if known) Name 7. Describe debtor's business A. Check one: Health Care Business (as defined in 11 U.S.C. -

Compos Mentis

composUndergraduate Journal mentis of Cognition and Neuroethics Volume 9, Issue 1 compos mentis Student Editor Coner Segren Production Editor Zea Miller Publication Details Volume 9, Issue 1 was digitally published in June of 2021 from Flint, Michigan, under ISSN: 2330-0264. © 2021 Center for Cognition and Neuroethics The Compos Mentis: Undergraduate Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics is produced by the Center for Cognition and Neuroethics. For more on CCN or this journal, please visit cognethic.org. Center for Cognition and Neuroethics University of Michigan-Flint Philosophy Department 544 French Hall 303 East Kearsley Street Flint, MI 48502-1950 Table of Contents 1 How the Self-Serving Attributional Bias Affects 1–12 Teacher Pedagogy Natalie Anderson 2 Murdoch’s Vision: Original-M vs. Brain-of-M 13–17 Betty Barnett 3 Coherent Infinitism as a Hybrid Model of Epistemic 19–36 Justification Luke Batt 4 Defending Free Will: A Libertarian’s Response to 37–45 Waller and Waller’s Challenge Mitchell Baty 5 Impoverished Bees: A Critical Analysis of Heidegger’s 47–66 Conception of Man as World-Forming and the Animal as Poor-In-World Abigail Bergeron 6 Issues Surrounding Attempts to Ground Political 67–78 Obligation in Gratitude Joshua Doland 7 Everyone’s a Critic: The Importance of Accountability 79–96 in Artistic Engagement and Creation Emma Fergusson Table of Contents (cont.) 8 The Moral Distinctiveness of Torture 97–103 Ethan Galanitsas 9 Putting the “Judge” in “Prejudice:” Neutralizing Anti- 105–117 discrimination Efforts Through Mischaracterizing -

100 Women Artists and Cultural Creators Respond to Centennial Of

100 Women Artists and Cultural Creators Respond to Centennial of the 19th Amendment and 100 Years of Women’s Suffrage in America in the Context of COVID and Black Lives Matter Cross-Disciplinary Group of Participants in 100 Years | 100 Women Initiative Includes Carrie Mae Weems, Deborah Willis, Toshi Reagon, Zoë Buckman, Andrea Jenkins, Meshell Ndegeocello, and Martha Redbone Commissioned by Park Avenue Armory with National Black Theatre and 9 Partner Cultural Institutions, New Works to be Launched Online on August 18 at Public Viewing Party New York, NY – August 4, 2020 – On August 18, marking the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, Park Avenue Armory and lead partner National Black Theatre, together with nine other New York City cultural institutions, will unveil the next phase of the 100 Years | 100 Women initiative. The project was launched in February 2020 with a day-long symposium and the announcement of the 100 commissioned artists and cultural creators who were invited to respond to and interrogate the complex legacy of women’s suffrage through their creative practices. In the time since, the creation of new works by the participants— including Zoë Buckman, Staceyann Chin, Karen Finley, Ebony Noelle Golden, Andrea Jenkins, Meshell Ndegeocello, Toshi Reagon, Martha Redbone, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis—has been shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing, #BlackLivesMatter, and a divisive election season. In lieu of the in-person celebration of the commissions that was planned for the spring, the Armory is hosting an online launch party streamed on YouTube on August 18 at 2pm, which will feature a sneak peek at select commissioned works, remarks by artists and partner organizations, and appearances by special guests including Maya Wiley, Susan Herman, Jari Jones, Tantoo Cardinal, Rita Dove, Catherine Gray, and the Kasibahagua Taíno Cultural Society. -

(C) 8:00 P.M. 1

f/Lc5 _.,,-------- TOWN OF SAN ANSELMO TOWN COUNCIL AGENDA October 25, 1994 Council Chambers -Town Hall 525 San Anselmo Avenue, San Anselmo 6:30 p.m. .. '· Open session to announce adjournment to closed session regarding negotiations with Peter and Pamela Fraser:, Hugh and Luanne Cadden, Ronald Lachman and Christine Troffer, Robert and Virginia Cary, David Ha.rlsen, Lewis Epstein, and Robert Pisarii, on the price and terms of payment for the purchase and exchange of real prop.erty in the vicinity of Bald Hill, Redwood Road, and Oak Avenue, AIP 7-101-01, 02, 7-071-01, 02, 03, and 7-154-01, 02, 03 and 04, ~d the Town-owned parcel on Indian Rock Court, AIP 177-250-55. 6:35 p.m. Closed session regarding: (A) Negotiations with Peter and Pamela Fraser, Hugh and Luanne Cadden, Ronald Lachman and Christine Troffer, Robert and Virginia Cary, David Hansen, Lewis Epstein, and Robert Pisani, on the purchase and exchange ofreal property in the vicinity of Bald Hill, Redwood Road, anq Oak Avenue, NP 7-101-01, 02, 7- 071~01, 02, 03, and 7-154-01, 02, 03 and 04, and the Town-owned parcel on Indian Rock Court, NP 177- 250-55. (B) Pending litigation pursuant to Government Code Section 54956;9(b)(l), regarding the subdivision of Lot 94, Bush Tract, Messrs. Mayne and Fitzgerald, property owners. (D) Pending litigation pursuant to Government Code Section 54956.9(a), San Anselmo v. Gill, et al,· Marin Supei:ior Court #155116. (C) Conference with labor negotiator (Town Administrator), regarding negotiatiOJJS with the Marin Association of Public Employees/SEID 949.