Chief Pleasant Porter: Preeminent Mediator of Creek and American Worlds by Nicholas Rinehart Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEQUOYA.Ii Constitu'tional Conveifflon 11

THE SEQUOYA.Ii CONSTITu'TIONAL CONVEifflON 11 THE SEQUOYAH CONSTITUTI OKAL CONVE?lTI ON AMOS DeZELL MAX'wELL,, Bachelor or Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater, Ok1ahana 191+8 Submitted to the Department of History Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Part1a1 Fu:l.f'illment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AR!S 195'0 111 OKLAHOMA '8BICULTUltAL & MlCHANICAL COLLE&I LIBRARY APR 241950 APPROVED Bia ) 250898 iv PREl'.lCE the Sequoy-ah Constitutional. Convention was held 1n Husk-0gee, Indian ferri to17, 1n. the aUBDller of 1905. It was the culminating event of a seriea ot eol.orrul occasions in the history or the .Five Civllized. Tribes. It was there that the deseendanta of those who made the trek west seventy-:f'ive years earlier sat with white men to vr1 te a eharter tor a new state.. They wrote a con st1tution, but it was never used as a charter tor a State or Sequo,yah. This work, which is primarily a stud,y or that convention and tbe reasons for its being called and its results, was undertaken at the suggestion of..,- father, Harold K. Max.well, in August, 1948. It has been carried to a conclusion through the a.id of a number o! persons, chief' among them being my wife, Betty Jo Max well. The need tor this study is a paramount one. Other than copies of the )(Q§koga f!l91P1J, the.re are no known records or the convention. Because much of the proceedings were in one or more Indian tongues there are some gaps in the study other than those due to the laek ot records,. -

Kevin E. Dudley, Et Al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma

INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS Alan Chapman; Kevin E. Dudley, et al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; Muskogee County, Oklahoma; Oklahoma Tax Commission; Harold Wade; Quik Trip, Inc., et al.; City of Catoosa, Oklahoma v. Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs 32 IBIA 101 (03/13/1998) Related Board case: 35 IBIA 285 United States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF HEARINGS AND APPEALS INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS 4015 WILSON BOULEVARD ARLINGTON, VA 22203 ALAN CHAPMAN, : Order Lifting Stay, Vacating Appellant : Decisions, and Remanding KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Cases Appellants : TOWN OF FORT GIBSON, OKLAHOMA, : Appellant : MUSKOGEE COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, : COMMISSIONERS, : Appellants : ALAN CHAPMAN, : Appellant : KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Docket No. IBIA 96-115-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 96-119-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-122-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-123-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-124-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-125-A HAROLD WADE, : Docket No. IBIA 97-2-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-3-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-10-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-11-A QUIK TRIP, INC., et al., : Docket No. IBIA 97-12-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 97-14-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-40-A Appellant : CITY OF CATOOSA, OKLAHOMA : Appellant : : v. : : MUSKOGEE AREA DIRECTOR, : BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, : Appellee : March 13, 1998 32 IBIA 101 These are consolidated appeals from four decisions of the Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs, to take certain tracts of land into trust. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Notice: study guide will be updated after the December general election. Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

Winter 2002 (PDF)

CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL ALSO INSIDE: EQUATIONS: AN INTERVIEW WITH BOB MOSES FLYING HISTORY AS SENTIMENTAL EDUCATION WHILE WHERE ARE YOU REALLY FROM? ASIAN AMERICANS AND THE PERPETUAL FOREIGNER SYNDROME ARAB MANAGING THE DIVERSITY Lessons from the Racial REVOLUTION: BEST PRACTICES FOR 21ST CENTURY BUSINESS Profiling Controversy U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, bipartisan agency first established by Congress in 1957. It is directed to: • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are being deprived of their right to Acting Chief vote by reason of their race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, Terri A. Dickerson or by reason of fraudulent practices; • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal Managing Editor protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, David Aronson age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Copy Editor • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to discrimination or denial of equal Dawn Sweet protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Editorial Staff • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or Monique Dennis-Elmore denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, Latrice Foshee disability, or national origin; Mireille Zieseniss • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress; • Issue public service announcements to discourage discrimination or denial of equal Interns protection of the laws. Megan Gustafson Anastasia Ludden In furtherance of its fact-finding duties, the Commission may hold hearings and issue Travis McClain subpoenas for the production of documents and the attendance of witnesses. -

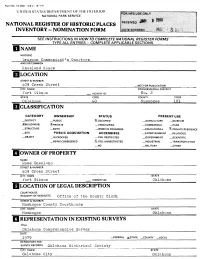

HCLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES •m^i:':^Mi:iMmm:mm-mmm^mmmmm:M;i:!m::::i!:- INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM 1 SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Dragoon Commandant's Quarters_____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON Kneeland House________________________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER /f09 Creek Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fort Gibs on _. VICINITY OF No. 2. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma uo Muskogee 101 HCLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ?_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT __|N PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ross Kneeland STREETS. NUMBER Creek Street CITY. TOWN STATE Fort Gibson VICINITY OF Oklahoma LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Muskogee County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Muskogee Oklahoma REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma City Oklahoma DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE XGOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Paint and a modern composition roof tend to disguise the age of the Dragoon Commandant's Quarters. -

The Past May Be Prologue, but It Does Not Dictate Our Future: This Is the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Table

Tulsa Law Review Volume 56 Issue 3 Special McGirt Issue Spring 2021 The Past May Be Prologue, But It Does Not Dictate Our Future: This Is the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Table Jonodev Chaudhuri Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonodev Chaudhuri, The Past May Be Prologue, But It Does Not Dictate Our Future: This Is the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Table, 56 Tulsa L. Rev. 369 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol56/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chaudhuri: The Past May Be Prologue, But It Does Not Dictate Our Future: Thi THE PAST MAY BE PROLOGUE, BUT IT DOES NOT DICTATE OUR FUTURE: THIS IS THE MUSCOGEE &5((. 1$7,21¶67$%/( Ambassador Jonodev Chaudhuri* I.INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 369 II.MUSCOGEE (CREEK)NATION¶S AMBASSADOR,CHITTO HARJO,PAVED THE WAY FOR OUR VICTORY IN MCGIRT .................................................................................. 371 III.THE MUSCOGEE (CREEK)NATION RESERVATION REMAINS TODAY ........................ 373 IV. MCGIRT UNDER ATTACK: THE PARALLELS TO THE FIGHTS AMBASSADOR CHITTO HARJO FOUGHT ................................................................................................. -

How Did the U.S. Government Finally Subdue the Indians?

Chapter How did the U.S. government finally subdue the Indians? How did courts and prisons operate in Indian Territory? For many years, there were no courts in Indian Territory with authority over 9 white people. As the number of whites in the area grew, this caused difficulties. So, in 1871, the federal court system gave authority to its District Court at Fort Smith, Arkansas, to try cases from Indian Terri- tory. The Fort Smith District Court would handle cases involving whites as well as cases of Indians charged with breaking federal laws. When it convicted defendants and sentenced them to prison, the Territory had to move them to a prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. Fort Smith was many miles from most settlements in Indian Terri- tory. Sometimes the greatest problem in bringing a lawbreaker to justice was getting him to court. Then if the court convicted him, another prob- lem was getting him to Kansas. Many men and a few women died on the trail to Fort Smith or Leavenworth. Some were law officers. Some were suspects or convicted criminals. However, considering the length of the journeys and the chances to escape, it is probably surprising that anyone ever completed it alive. What attracted outlaws to Indian Territory? With justice far away, numerous criminals found the Territory the perfect place to stay. Outlaws such as Jim Reed, Jesse James, Cole Younger, and Bill Doolin often took refuge in Indian Territory. A favorite stopover was “Young- er’s Bend,” a farm belonging to Belle Starr. Outlaws in Indian Territory came from a variety of backgrounds. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

A Five Minute History of Oklahoma

Chronicles of Oklahoma Volume 13, No. 4 December, 1935 Five Minute History of Oklahoma Patrick J. Hurley 373 Address in Commemoration of Wiley Post before the Oklahoma State Society of Washington D. C. Paul A. Walker 376 Oklahoma's School Endowment D. W. P. 381 Judge Charles Bismark Ames D. A. Richardson 391 Augusta Robertson Moore: A Sketch of Her Life and Times Carolyn Thomas Foreman 399 Chief John Ross John Bartlett Meserve 421 Captain David L. Payne D. W. P. 438 Oklahoma's First Court Grant Foreman 457 An Unusual Antiquity in Pontotoc County H. R. Antle 470 Oklahoma History Quilt D. W. P. 472 Some Fragments of Oklahoma History 481 Notes 485 Minutes 489 Necrology 494 A FIVE MINUTE HISTORY OF OKLAHOMA By Patrick J. Hurley, former Secretary of War. From a Radio Address Delivered November 14, 1935. Page 373 The State of Oklahoma was admitted to the Union 28 years ago. Spaniards led by Coronado traversed what is now the State of Oklahoma 67 years before the first English settlement in Virginia and 79 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. All of the land now in Oklahoma except a little strip known as the panhandle was acquired by the United States from France in the Louisiana Purchase. Early in the nineteenth century the United States moved the five civilized tribes, the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, from southeastern states to lands west of the Mississippi River, the title to which was transferred to the tribes in exchange for part of their lands in the East. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Studies in American Indian Literatures Editors James H

volume 21 . number 3 . fall 2009 Studies in American Indian Literatures editors james h. cox, University of Texas at Austin daniel heath justice, University of Toronto Published by the University of Nebraska Press The editors thank the Centre for Aboriginal Initiatives at the University of To- ronto and the College of Liberal Arts and the Department of English at the Uni- versity of Texas for their fi nancial support. subscriptions Studies in American Indian Literatures (SAIL ISSN 0730-3238) is the only schol- arly journal in the United States that focuses exclusively on American Indian lit- eratures. SAIL is published quarterly by the University of Nebraska Press for the Association for the Study of American Indian Literatures (ASAIL). Subscription rates are $38 for individuals and $95 for institutions. Single issues are available for $22. For subscriptions outside the United States, please add $30. Canadian subscribers please add appropriate GST or HST. Residents of Nebraska, please add the appropriate Nebraska sales tax. To subscribe, please contact the Univer- sity of Nebraska Press. Payment must accompany order. Make checks payable to the University of Nebraska Press and mail to The University of Nebraska Press PO Box 84555 Lincoln, NE 68501-4555 Phone: 402-472-8536 Web site: http://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu All inquiries on subscription, change of address, advertising, and other business communications should be addressed to the University of Nebraska Press at 1111 Lincoln Mall, Lincoln, NE 68588-0630. A subscription to SAIL is a benefi t of membership in ASAIL. For member- ship information please contact R. M. Nelson 2421 Birchwood Road Henrico, VA 23294-3513 Phone: 804-672-0101 E-mail: [email protected] submissions The editorial board of SAIL invites the submission of scholarly manuscripts fo- cused on all aspects of American Indian literatures as well as the submission of poetry and short fi ction, bibliographical essays, review essays, and interviews. -

Fort Gibson National Cemetery Rostrum Is Located at Latitude 35.805259, Longitude -95.230778 (North American Datum of 1983)

HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY FORT GIBSON NATIONAL CEMETERY, ROSTRUM HALS No. OK-3-B Location: 1423 Cemetery Road, Fort Gibson, Muskogee County, Oklahoma The Fort Gibson National Cemetery rostrum is located at latitude 35.805259, longitude -95.230778 (North American Datum of 1983). The coordinate represents the structure’s approximate center. Present owner: National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Construction date: 1939 Builder / Contractor: unknown Description: The rostrum is an octagonal platform about 15' wide x 4' high. It is built of rock-faced local sandstone blocks of varying lengths with 1" margins laid in regular courses. A 6"-thick concrete pad sits atop and overhangs the platform. Eight five-sided cast-concrete posts stand at the corners of this pad. These posts support cast-concrete handrails, two rails running between each post. A flight of seven concrete steps leads onto the rostrum floor on the north side. It is flanked by sandstone cheek walls coped with cast-concrete blocks. Site context: The cemetery was originally a 6.9-acre rectangle laid out around a central flagpole mound. Numerous additions have enlarged the grounds to over 48 acres and given it an irregular L shape. The rostrum, used as a speaker’s stand on ceremonial occasions, is sited in the oldest part of the cemetery, in what is now Section 7, 170' southwest of the entrance gates. Its stairs face generally north, toward the main road that passes the cemetery. History: The national cemetery at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), was established in 1868 on land previously used as a post cemetery.