Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Civil War (Part II)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY CONTENTS Major-General John Campbell in British West Florida George C

Volume XXVII April 1949 Number 4 The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY CONTENTS Major-General John Campbell in British West Florida George C. Osborn Nocoroco, a Timucua Village of 1605 John W. Griffin Hale G. Smith The Founder of the Seminole Nation Kenneth W. Porter A Connecticut Yankee after Olustee Letters from the front Vaughn D. Bornet Book reviews: Kathryn Abbey Hanna: “Florida Land of Change” Paul Murray: “The Whig Party in Georgia, 1825-1853” Herbert J. Doherty Jr. Local History: “The Story of Fort Myers” Pensacola Traditions The Early Southwest Coast Early Orlando “They All Call it Tropical” The Florida Historical Society A noteworthy gift to our library List of members Contributors to this number SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS SINGLE COPIES ONE DOLLAR (Copyright, 1949, by the Florida Historical Society. Reentered as second class matter November 21, 1947, at the post office at Tallahassee, Florida, under the Act of August 24, 1912.) Office of publication, Tallahassee, Florida Published quarterly by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY St. Augustine, Florida MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN CAMPBELL IN BRITISH WEST FLORIDA by GEORGE C. OSBORN Late in the autumn of 1778 Brigadier-General John Campbell received a communication from Lord George Germain to proceed from the colony of New York to Pensacola, Province of West Florida.1 In this imperial province, which was bounded on the west by the Missis- sippi river, Lake Ponchartrain and the Iberville river, on the south by the Gulf of Mexico, on the east by the Apalachicola river and on the north by the thirty-first parallel but later by a line drawn eastward from the mouth of the Yazoo river,2 General Campbell was to take command of His Majesty’s troops. -

Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: a Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War

CHIEF BOWLEGS AND THE BANANA GARDEN: A REASSESSMENT OF THE BEGINNING OF THE THIRD SEMINOLE WAR by JOHN D. SETTLE B.A. University of Central Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Daniel Murphree © 2015 John Settle ii ABSTRACT This study examines in depth the most common interpretation of the opening of the Third Seminole War (1855-1858). The interpretation in question was authored almost thirty years after the beginning of the war, and it alleges that the destruction of a Seminole banana plant garden by United States soldiers was the direct cause of the conflict. This study analyzes the available primary records as well as traces the entire historiography of the Third Seminole War in order to ascertain how and why the banana garden account has had such an impactful and long-lasting effect. Based on available evidence, it is clear that the lack of fully contextualized primary records, combined with the failure of historians to deviate from or challenge previous scholarship, has led to a persistent reliance on the banana garden interpretation that continues to the present. Despite the highly questionable and problematic nature of this account, it has dominated the historiography on the topic and is found is almost every written source that addresses the beginning of the Third Seminole War. This thesis refutes the validity of the banana garden interpretation, and in addition, provides alternative explanations for the Florida Seminoles’ decision to wage war against the United States during the 1850s. -

Fort King National Historic Landmark Education Guide 1 Fig5

Ai-'; ~,,111m11l111nO FORTKINO NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Fig1 EDUCATION GUIDE This guide was made possible by the City of Ocala Florida and the Florida Department of State/Division of Historic Resources WELCOME TO Micanopy WE ARE EXCITED THAT YOU HAVE CHOSEN Fort King National Historic Fig2 Landmark as an education destination to shed light on the importance of this site and its place within the Seminole War. This Education Guide will give you some tools to further educate before and after your visit to the park. The guide gives an overview of the history associated with Fort King, provides comprehension questions, and delivers activities to Gen. Thomas Jesup incorporate into the classroom. We hope that this resource will further Fig3 enrich your educational experience. To make your experience more enjoyable we have included a list of items: • Check in with our Park Staff prior to your scheduled visit to confrm your arrival time and participation numbers. • The experience at Fort King includes outside activities. Please remember the following: » Prior to coming make staff aware of any mobility issues or special needs that your group may have. » Be prepared for the elements. Sunscreen, rain gear, insect repellent and water are recommended. » Wear appropriate footwear. Flip fops or open toed shoes are not recommended. » Please bring lunch or snacks if you would like to picnic at the park before or after your visit. • Be respectful of our park staff, volunteers, and other visitors by being on time. Abraham • Visitors will be exposed to different cultures and subject matter Fig4 that may be diffcult at times. -

Kevin E. Dudley, Et Al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma

INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS Alan Chapman; Kevin E. Dudley, et al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; Muskogee County, Oklahoma; Oklahoma Tax Commission; Harold Wade; Quik Trip, Inc., et al.; City of Catoosa, Oklahoma v. Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs 32 IBIA 101 (03/13/1998) Related Board case: 35 IBIA 285 United States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF HEARINGS AND APPEALS INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS 4015 WILSON BOULEVARD ARLINGTON, VA 22203 ALAN CHAPMAN, : Order Lifting Stay, Vacating Appellant : Decisions, and Remanding KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Cases Appellants : TOWN OF FORT GIBSON, OKLAHOMA, : Appellant : MUSKOGEE COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, : COMMISSIONERS, : Appellants : ALAN CHAPMAN, : Appellant : KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Docket No. IBIA 96-115-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 96-119-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-122-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-123-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-124-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-125-A HAROLD WADE, : Docket No. IBIA 97-2-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-3-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-10-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-11-A QUIK TRIP, INC., et al., : Docket No. IBIA 97-12-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 97-14-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-40-A Appellant : CITY OF CATOOSA, OKLAHOMA : Appellant : : v. : : MUSKOGEE AREA DIRECTOR, : BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, : Appellee : March 13, 1998 32 IBIA 101 These are consolidated appeals from four decisions of the Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs, to take certain tracts of land into trust. -

Territorial Florida Castillo De San Marcos National Monument Second Seminole War, 1835-1842 St

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Territorial Florida Castillo de San Marcos National Monument Second Seminole War, 1835-1842 St. Augustine, Florida ( Seminole Indians, c. 1870 Southern Migration The original native inhabitants of Florida had all but disappeared by 1700. European diseases and the losses from nearly constant colonial warfare had reduced the population to a mere handful. Bands from various tribes in the southeastern United States pressured by colonial expansion began moving into the unoccupied lands in Florida. These primarily Creek tribes were called Cimarrones by the Spanish “strays” or “wanderers.” This is the probable origin of the name Seminole. Runaway slaves or “Maroons” also began making their way into Florida where they were regularly granted freedom by the Spanish. Many joined the Indian villages and integrated into the tribes. Early Conflict During the American Revolution the British, who controlled Florida from 1763 to 1784, recruited the Seminoles to raid rebel frontier settlements in Georgia. Both sides engaged in a pattern of border raiding and incursion which continued sporadically even after Florida returned to Spanish control after the war. Despite the formal treaties ending the war the Seminoles remained enemies of the new United States. Growing America At the beginning of the 19th century the rapidly growing American population was pushing onto the frontiers in search of new land. Many eyes turned southward to the Spanish borderlands of Florida and Texas. Several attempts at “filibustering,” private or semi-official efforts to forcibly take territory, occurred along the frontiers. The Patriot War of 1812 was one such failed American effort aimed at taking East Florida. -

Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: a Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: A Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War John Settle University of Central Florida Part of the Public History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Settle, John, "Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: A Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1177. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1177 CHIEF BOWLEGS AND THE BANANA GARDEN: A REASSESSMENT OF THE BEGINNING OF THE THIRD SEMINOLE WAR by JOHN D. SETTLE B.A. University of Central Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Daniel Murphree © 2015 John Settle ii ABSTRACT This study examines in depth the most common interpretation of the opening of the Third Seminole War (1855-1858). The interpretation in question was authored almost thirty years after the beginning of the war, and it alleges that the destruction of a Seminole banana plant garden by United States soldiers was the direct cause of the conflict. -

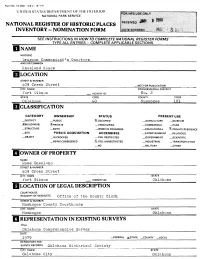

HCLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES •m^i:':^Mi:iMmm:mm-mmm^mmmmm:M;i:!m::::i!:- INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM 1 SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Dragoon Commandant's Quarters_____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON Kneeland House________________________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER /f09 Creek Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fort Gibs on _. VICINITY OF No. 2. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma uo Muskogee 101 HCLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ?_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT __|N PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ross Kneeland STREETS. NUMBER Creek Street CITY. TOWN STATE Fort Gibson VICINITY OF Oklahoma LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Muskogee County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Muskogee Oklahoma REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma City Oklahoma DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE XGOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Paint and a modern composition roof tend to disguise the age of the Dragoon Commandant's Quarters. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

Seminole Origins

John and Mary Lou Missall A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SEMINOLE WARS SEMINOLE WARS FOUNDATION, INC. Founded 1992 Pamphlet Series Vol. I, No. 2 2006 Copyright © 2006 By John & Mary Lou Missall Series Editor: Frank Laumer Seminole Wars Foundation, Inc. 35247 Reynolds St. Dade City, FL 33523 www.seminolewars.us 2 Florida During the Second Seminole War 3 The Seminole Wars Florida’s three Seminole Wars were important events in American history that have often been neglected by those who tell the story of our nation’s past. These wars, which took place between the War of 1812 and the Civil War, were driven by many forces, ranging from the clash of global empires to the basic need to protect one’s home and family. They were part of the great American economic and territorial expansion of the nineteenth century, and were greatly influenced by the national debate over the issue of slavery. In particular, the Second Seminole War stands out as the nation’s longest, costli- est, and deadliest Indian war. Lasting almost seven years, the conflict cost thousands of lives and millions of dollars, yet faded from the nation’s collective memory soon after the fighting ended. It is a story that should not have been forgotten, a story that can teach us lessons that are still relevant today. It is in hopes of restoring a portion of that lost mem- ory that the Seminole Wars Foundation offers this short history of one of our nation’s longest wars. Seminole Origins The ancestors of the Seminole Indians were primarily Creek Indians from Georgia and Alabama who migrated to Florida during the 18th century after the decimation of the aboriginal natives under Spanish rule. -

Fort Gibson National Cemetery Rostrum Is Located at Latitude 35.805259, Longitude -95.230778 (North American Datum of 1983)

HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY FORT GIBSON NATIONAL CEMETERY, ROSTRUM HALS No. OK-3-B Location: 1423 Cemetery Road, Fort Gibson, Muskogee County, Oklahoma The Fort Gibson National Cemetery rostrum is located at latitude 35.805259, longitude -95.230778 (North American Datum of 1983). The coordinate represents the structure’s approximate center. Present owner: National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Construction date: 1939 Builder / Contractor: unknown Description: The rostrum is an octagonal platform about 15' wide x 4' high. It is built of rock-faced local sandstone blocks of varying lengths with 1" margins laid in regular courses. A 6"-thick concrete pad sits atop and overhangs the platform. Eight five-sided cast-concrete posts stand at the corners of this pad. These posts support cast-concrete handrails, two rails running between each post. A flight of seven concrete steps leads onto the rostrum floor on the north side. It is flanked by sandstone cheek walls coped with cast-concrete blocks. Site context: The cemetery was originally a 6.9-acre rectangle laid out around a central flagpole mound. Numerous additions have enlarged the grounds to over 48 acres and given it an irregular L shape. The rostrum, used as a speaker’s stand on ceremonial occasions, is sited in the oldest part of the cemetery, in what is now Section 7, 170' southwest of the entrance gates. Its stairs face generally north, toward the main road that passes the cemetery. History: The national cemetery at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), was established in 1868 on land previously used as a post cemetery. -

Seminole War Period Towns and Camps Tallahassee

Seminole War period Towns and Camps Tallahassee Tallahassee (Also called Anhaica) was home to thousands of Muskogee speaking people. American forces burned Tallahasee to the ground at the start of the war. Later American settlers would build their own city, while keeping the Native name. Miccosukee Like Tallahassee, Miccosukee was a large town, with thousands of people living there. It was targeted early by Americans, who plundered and raised the town. Suwanee River This river was home to both Seminole people and free Black communities. The Black communities were largely made of escaped slaves from American plantations, but many in the early 1800s were born free in Florida. The two communities traded and worked together, and many Americans referred to them as Black Seminoles. Big City Island Long a home to the Tequesta people, Big City Island was a refuge for Seminole people during the War until Fort Lauderdale was established. Sam Jones Camp (Treetops) Abiaka (Sam Jones) established this camp during the war to be far from the Front Lines of battle Billy Bowlegs Village Billy Bowlegs and his family made their homes here during the height of the War. Billy Bowlegs Camp 3rd The home camp of Billy Bowlegs when he led the Seminole near the end of the War. It was sacked by U.S. Army scouts, and the retaliation led to a new declaration of war by the United States. Sam Jones Town (BC) Abiaka (Sam Jones) chose this area to evade American patrols. He and his followers remained hidden through the end of the War. -

A Diary of the Billy Bowlegs War

"The Firing of Guns and Crackers Continued Till Light" A Diary of the Billy Bowlegs War edited with commentary by Gary R. Mormino Historians have evoked a number of powerful metaphors to capture the spirit of the American adventure, but none arouses more emotion than the image of the frontier. The sweep across the con- tinent, the inexorable push westward emboldened democratic rhetoric and rugged individualism. Free land awaited pioneers willing to fight Indians. South Florida played a critical role in the history of the American frontier. At a time when fur trappers and mountain men explored the Rocky Mountains, the region south of Tampa was virgin territory. The erection of Fort Brooke in 1824 played a paradoxical role in the development of Tampa; on the one hand, it served as the begin- ning of the modern city; on the other hand, military regulations encumbered civilian growth around the fort. Tampa was to be the cutting edge of the newest frontier, an ethnic beachhead for Irish soldiers, Southern cavaliers, New England Yankees, African slaves, and Seminole warriors. In the 1830s it was a collection of wildly divergent ethnic groups held together by the rigorous demands of frontier life, and, after 1835, the omnipresent fear of Indian attack. A clash of people tested the future of Florida. Would the future architects of South Florida be homesteading pioneers or Seminole Indians? Would Tampa be cordoned by a 256-mile military reserva- tion, or be thrown open to homesteading white settlers? Two terrible wars were fought to answer these questions. Gary Mormino is an associate professor of history at the University of South Florida in Tampa and executive director of the Florida Historical Society.