Color, Grisaille and Pictorial Techniques in Works by Jean Pucelle Pascale Charron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painting: Color and Technique – ART 2010

Painting: Color and Technique – ART 2010 Spring 2020 Meeting days: Tuesday, Thursday Instructor: Karah Lain, MFA Meeting times: 9:00-11:20AM E-mail: [email protected] Meeting location: Keller 109 Office location: Starkey B, Room 108 Final Exam: Tuesday, May 5 Office hours: Mon/Wed/Fri 10:30AM-1PM 10:30AM – 1PM (and by appointment) CATALOG DESCRIPTION Introduction to the techniques, expressive qualities, and criticism of oil painting media. Additional description: This course offers an introduction to a variety of foundational oil painting techniques and processes, including direct and indirect painting methods, color mixing strategies, and methods for developing compositional effectiveness. Through an introduction to a variety of precedents for painting, the course is also meant to promote the development of conceptual ideation, personal voice, and historical contextualization in a personal painting practice. To this end, instruction will be given through lectures, demonstrations, one-on-one discussions, group discussions, hands-on experience, readings, videos, critiques, and a studio visit with a working artist from the area. LEARNING OUTCOMES Students will be able to: 1. Understand and utilize safe and effective studio methods for painting in oil. 2. Paint directly and indirectly, using a variety of painting techniques to this end. 3. Intentionally mix colors to achieve a range of effects. 4. Create a dynamic compositional structure in painting. 5. Develop personally relevant conceptual content for their work and communicate such content through painting. 6. Show an awareness of a range of precedents for painting, and apply this awareness to their painting practice, in order to begin contextualizing their work within painting’s history. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited 2 Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited

Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited 2 Bruegel in Black and White Three Grisailles Reunited Karen Serres with contributions by Dominique Allart, Ruth Bubb, Aviva Burnstock, Christina Currie and Alice Tate-Harte First published to accompany Bruegel in Black and White: Three Grisailles Reunited The Courtauld Gallery, London, 4 February – 8 May 2016 The Courtauld Gallery is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) Copyright © 2016 Texts copyright © the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. isbn 978 1 907372 94 0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Produced by Paul Holberton publishing 89 Borough High Street, London se1 1nl www.paul-holberton.net Designed by Laura Parker www.parkerinc.co.uk Printing by Gomer Press, Llandysul front cover and page 7: Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (cat. 3), detail frontispiece: Three Soldiers, 1568 (cat. 8), detail page 8: The Death of the Virgin, c. 1562–65 (cat. 1), detail contributors to the catalogue da Dominique Allart ab Aviva Burnstock rb Ruth Bubb cc Christina Currie ks Karen Serres at-h Alice Tate-Harte Foreword This focused exhibition brings together for the first At the National Trust, special thanks are due to David time Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s three surviving grisaille Taylor, Christine Sitwell, Fernanda Torrente and the staff paintings and considers them alongside closely related at Upton House. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 30 October 2017 – 18 February 2018 Sainsbury Wing Admission charge See differently At the National Gallery this autumn, journey through a world of shadow and light. With more than fifty painted objects created over 700 years, Monochrome: Painting in Black and White is a radical new look at what happens when artists cast aside the colour spectrum and focus on the visual power of black, white, and everything in between. Paintings by Old Masters such as Jan van Eyck, Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres appear alongside works by some of the most exciting contemporary artists working today including Gerhard Richter, Chuck Close, and Bridget Riley. Olafur Eliasson‘s immersive light installation Room for one colour (1997) brings a suitably mind-altering coda to the exhibition. With major loans from around the world, and works from the National Gallery’s Collection, Monochrome reveals fresh insights into the use of colour as a choice rather than a necessity. As Lelia Packer and Jennifer Sliwka, curators of Monochrome: Painting in Black and White, explain, “Painters reduce their colour palette for many reasons, but mainly as a way of focusing the viewer’s attention on a particular subject, concept or technique. It can be very freeing - without the complexities of working in colour, you can experiment with form, texture, mark making, and symbolic meaning.” Monochrome: Painting in Black and White guides visitors through seven rooms, each addressing a different aspect of painting in black, white and grey, also known as grisaille: Sacred Subjects The earliest surviving works of Western art made in grisaille were created in the Middle Ages for devotional purposes, to eliminate distractions, and focus the mind. -

On Making a Film of the MYSTIC LAMB by Jan Van Eyck

ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 Figure 1 The Mystic Lamb (1432), Jan van Eyck. Closed Wings. On Making a film of THE MYSTIC LAMB by Jan van Eyck Jules Cashford Accompanying sample clip of the Annunciation panel, closed wings middle register from DVD is available free on YouTube here. Full Length DVDs are also available. Details at the end of this article. The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. 1 ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 Figure 2 The Mystic Lamb (1432), Jan van Eyck. Open Wings. The Mystic Lamb by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) The Mystic Lamb (1432), or the Ghent Altarpiece, in St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, is one of the most magnificent paintings of the Early Northern Renais- sance. It is an immense triptych, 5 meters long and 3 meters wide, and was origi- nally opened only on feast days, when many people and painters would make a pilgrimage to be present at the sacred ritual. They could see – when the wings were closed – the annunciation of the Angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, which The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. 2 ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 they knew as the Mystery of the Incarnation. But when the wings were opened they would witness and themselves participate in the revelation of the new order: the Lamb of God, the story of Christendom, and the redemption of the World. -

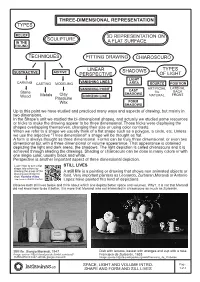

Techniques Three-Dimensional Representation 3D Representation on a Flat Surface Types Sculpture Chiaroscuro Fitting Drawing Type

THREE-DIMENSIONAL REPRESENTATION TYPES RELIEF 3D REPRESENTATION ON SCULPTURE IN THE A FLAT SURFACE ROUND TECHNIQUES FITTING DRAWING CHIAROSCURO LINEAR SHADOWS TYPES SUSTRACTIVE ADITIVE PERSPECTIVE OF LIGHT LIGHT VANISHING LINES CARVING CASTING MODELING AREA SOURCE POSITION VANISHING POINT ARTIFICIAL LATERAL Stone CAST Vs BACK Clay SHADOWS Wood Metals HORIZON LINE NATURAL FRONT Plasticine Wax FORM SHADOWS Up to this point we have studied and practiced many ways and aspects of drawing, but mainly in two dimensions. In the Shape's unit we studied the bi-dimensional shapes, and actually we studied some resources or tricks to make the drawing appear to be three dimensional. Those tricks were displaying the shapes overlapping themselves, changing their size or using color contrasts. When we refer to a shape we usually think of a flat shape such as a polygon, a circle, etc. Unless we use the adjective "Three dimensional" a shape will be thought as flat. A form is always thought as three dimensional. Forms can be truly three dimensional, or even two dimensional but with a three dimensional or volume appearance. That appearance is obtained depicting the light and dark areas, the shadows. The light depiction is called chiaroscuro and it is achieved through shading the drawings. Shading or chiaroscuro can be done in many colors or with one single color, usually black and white. Perspective is another important aspect of three dimensional depiction. Learn How to turn a flat STILL LIVES shape into a form by shading the areas of the A still life is a painting or drawing that shows non animated objects or drawing watching this short Youtube video food. -

Why Was Jan Van Eyck Here? the Subject, Sitters, and Significance of the Arnolfini Marriage Portrait

Venezia Arti [online] ISSN 2385-2720 Vol. 26 – Dicembre 2017 [print] ISSN 0394-4298 Why Was Jan van Eyck here? The Subject, Sitters, and Significance of The Arnolfini Marriage Portrait Benjamin Binstock (Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York City, USA) Abstract Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Marriage Portrait of 1434 still poses fundamental questions. An overlooked account explained the groom’s left hand holding his bride’s right hand as a secular, legal morganatic marriage with a bride of lower social rank and wealth. That would explain Van Eyck’s presence as witness in the mirror and through his inscription, and corresponds to the recent identification of the bride and groom as Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his previously unknown first wife Helene of unknown last name. Van Eyck’s scene can be called the first modern painting, as the earliest autonomous, illusionistic representation of secular reality, provided with the earliest artist’s signature of the modern type, framing his scene as perceived and represented by a particular individual. That is why Jan van Eyck was here. Summary 1 What is being disguised: religious symbolism or secular art? – 2 A morganatic, left-handed marriage. – 3 The sitters: Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his first wife Helene? – 4 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait as the first modern painting. – 5 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait within his oeuvre and tradition. – 6 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait and art historical method. Keywords Jan van Eyck. Signature. Arnolfini. Morganatic Marriage. Modern painting. For Marek Wieczorek What is the hardest of all? What you think is the easiest. -

OIL PAINTING GLOSSARY Alkyd (Pronounced: Al-Kid)

OIL PAINTING GLOSSARY Alkyd (Pronounced: al-kid) An alkyd is a synthetic resin that can be added to oil paint to speed up the drying time of oil paints. You can buy an alkyd-based medium that you can mix in with your oils; the most commonly available is Liquin by Winsor & Newton. “Alla Prima” (Pronounced: ah-luh pree-ma) Alla Prima is an Italian oil painting technique, usually from life, in which the entire painting is completed in one session or while the paint is still wet. Usually, there isn’t any underpainting to the piece. Portraits, landscapes, and still life are common subject matter using alla prima. It translates as “at the first”. In past eras, it was used primarily as a means of sketching, but eventually, it became a means of producing finished works of art by the Impressionists. “Bistre” Bistre (“the wipe-out method”) is an underpainting using warm browns (usually raw umber or burnt umber). A thin wash of Raw umber is painted over the white canvas and then ‘wiped out’ to create a tonal underpainting. The shadows are built up using thin color, allowing the warmth of the brown to show through while the lights and midtones are applied as opaque color. You can also use Burnt Umber for an even warmer, darker underpainting. The Bistre method lends itself very well to chiaroscuro. Chiaroscuro (Pronounced: key-ARE-oh-SCURE-oh) Chiaroscuro is an Italian word literally meaning “light dark”, used to describe the skillful balance of light and dark in a painting with strong contrasts to create a dramatic effect. -

Leonardo's Colour and Chiaroscuro Author(S): John Shearman Source: Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, 25

Leonardo's Colour and Chiaroscuro Author(s): John Shearman Source: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 25. Bd., H. 1 (1962), pp. 13-47 Published by: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH Munchen Berlin Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1481484 . Accessed: 27/02/2014 13:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH Munchen Berlin is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.111.215.12 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 13:46:34 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LEONARDO'S COLOUR AND CHIAROSCURO By JohnShearman It is unfortunatelythe case that the analysis and interpretationof colour in paintings lags far behind other aspects of formal historical criticism.The subject seems to be in some degree of dis- repute,or at the best open to suspicion,and not without reason. It is rare that observationsin this field descend fromthe general to the particular1, or fromfrank subjectivity(even quasi-mysticism) to the admittedlymore tedious but ultimatelymore rewardingobjectivity that is, for example, nor- mally regarded as indispensablein modern studies of perspective.The following study was under- taken in the belief that colour (and its dependents,light and chiaroscuro)can just as well be sub- 2 mittedto argumentand historicalcriticism The analogy between perspectiveand colour is not casual. -

The Friedsam Annunciation and the Problem of the Ghent Altarpiece Author(S): Erwin Panofsky Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

The Friedsam Annunciation and the Problem of the Ghent Altarpiece Author(s): Erwin Panofsky Reviewed work(s): Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Dec., 1935), pp. 432-473 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3045596 . Accessed: 14/06/2012 19:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org THE FRIEDSAM ANNUNCIATIONAND THE PROBLEMOF THE GHENT ALTARPIECE By ERWIN PANOFSKY N 1932 the collection of Early Flemish paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of New York was enriched by a fine and rather enigmatical Annunciation acquired and formerly owned by Col. Michael Friedsam (Fig. I). It has been tentatively attributed to Petrus Cristus, with the reservation, however, that it is "almost a van Eyck."1 To the attribution to Petrus Cristus there are several objections. The Friedsam painting does not show the technical characteristics of the other works by this master (the handling of the medium being "more archaic," as I learn from an eminent American X-ray expert,2 nor does it fit into his artistic development. -

Notes on Ingres' Odalisque En Grisaille

International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2017 Notes on Ingres’ Odalisque en grisaille Daniele Iozzia Department of Humanities University of Catania Piazza Dante 32, 95124 Catania, Italy Abstract The Odalisque en Grisaille raises questions about its attribution to Ingres and moreover about the reasons why it was painted. Through analysis of Ingres’ reflections on the importance of drawing over colour, this paper proposes a new hypothesis about the nature of the painting: that it could have been a studio exercise executed by the painter with his pupils in order to help them understand the value of monochrome. Keywords: monochrome, nude, studio practice, chiaroscuro An important section of Ingres’ thoughts concerns the problem of what is most important in art. Ingres’ position, which in this sense is strictly classical, is unambiguous in assigning supremacy to drawing, in accordance with the theories that already circulated in the Renaissance and which had led to the dispute between the supporters of the Florentine school of drawing and those of the Venetian school of colour. Ingres’ reflections, however, do not consitute a specifically theoretical position but are presented more as a recommendation for studio practice to his students. This is especially the case when he states that drawing is what contributes in the largest proportion to the success of a picture, while what colour brings to a painting is minimal and to some extent superficial: Dessiner ne veut pas dire simplement reproduire des contours, le dessin ne consiste pas simplement dans le trait: le dessin c’est encore l'expression, la forme intérieure, le plan, le modelé. -

Luxembourg & Dayan to Present Grisaille

LUXEMBOURG & DAYAN TO PRESENT GRISAILLE MASTERwORkS iN GREY wiLL GO ON viEw Simultaneously iN NEw YORk AND LONDON, inauguratiNG gallery’S NEw U.k. spacE London October 9, 2011 — December 23, 2011 New York November 7, 2011 — January 14, 2012 For Immediate Release Media Contact: Andrea Schwan, Andrea Schwan Inc. +1 917 371.5023 [email protected] © 2011 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. NEw YORk, NY...Taking a monochromatic grey palette as its organizing principle, Luxembourg & Dayan’s upcoming exhibition Grisaille will explore the conceptual impact of a centuries-old painting paradigm upon key figures of modern and contemporary art. In addition to a concise selection of rare historical works, including a pair of 16th century panel paintings by the Workshop of Albrecht Dürer, Grisaille will include more than 30 seminal pieces by artists as diverse as César, Glenn Brown, Vija Celmins, Pablo Picasso, Gerhard Richter, Rudolf Stingel, Betty Tompkins, and numerous others whose investigation of the monochrome palette and classical techniques have brought the vitality of grisaille’s history into the 21st first century. 1 of 4 Grisaille will unfold across two locations on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. One portion of the exhibition will open in London on October 9, 2011, inaugurating Luxembourg & Dayan’s new viewing space at 2 Savile Row. The balance of the exhibition will be unveiled in New York City on November 7th, filling the gallery’s Upper East Side townhouse. Grisaille will remain on view in both venues through January 14, 2012. Grisaille is the second in a series of thematic survey exhibitions at Luxembourg & Dayan to be organized by curator and writer Alison Gingeras, exploring specific trends in modern and contemporary art.