Why Dogs Stopped Flying: Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josephine Miles, Poetry and Change

REVIEW Josephine Miles, Poetry and Change Robert F. Gleckner Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 9, Issue 4, Spring 1976, pp. 133-136 133 The elements of this final design, however, are often subtle, difficult to talk about, though modern linguistic study (to which Professor Miles acknowledges a major debt) helps us to discriminate Josephine Miles. Poetry and Change. Berkeley, "not merely obvious visual surfaces but auditory Los Angeles, London: University of California echoes, semantic associations, structural Press, 1974. 243 pp. $10.75. similarities which may work below the surface but are also implied in the surface richness" (9). With a sense of these, "the articulatable parts Reviewed by Robert F. Gleckner of language," we can "see and hear more, . feel more, of the poem's entity" (11). Style, then (in which Professor Miles includes not only From 1964, when she published Eras and Modes in use of language but also "style of moral judgments" English Poetry3 to her 1973 essay on "Blake's Frame and "style of attitude toward the reader"), is a of Language" Josephine Miles has been grappling product of a "number of small recurring selections with the problems facing all who wish intelligently and arrangements working together," a process of to study the language of poetry and prose. Her "creating and reshaping expectations which design work has ranged from the early Renaissance to contrives" (16). British and American writing of the twentieth- century, including a number of young poets writing The change in poetry observable through -

John W. Ehrstine, William Blake's Poetical Sketches

REVIEW John W. Ehrstine, William Blake’s Poetical Sketches Michael J. Tolley Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 2, Issue 3, December 15, 1968, pp. 55-57 -55- ; ' •.' • -.' ; : >• '■ * ■ REVIEW ' --; ■- - '■ :<x .■■•■■ ■ \,' oz Bweoq n#t Wi 11iam Blake's Poetical Sketches, by John W. Ehrstine. Washington State University Press (1967), pp. DO + 108 pp. '■■■><' It is a pity that the first fulllength study of the Poetical Sketched to be published since Margaret Ruth Lowery's pioneering work of 1940 should be so little worthy the serious attention of a Blake student. Ehrstine is one of the familiar new breed of academic bookproducers, whose business is not scholarship but novel thesisweaving* Having assimilated certain ideas and critical tech niques, they apply them ruthlessly to any work that has hithertobeen fortunate enough to escape such attentions. The process is simple and: the result—that of bookproduction—is infallible. If the poor little poems protest while struggling in their Procrustean bed, one covers their noise with bland asser' 1" tions and continues to mutilate them. Eventually they satisfy one's preconcep" tions. Unfortunately, they may also impose on other people. In revewing such books one must blame mainly the publishers and their advisors; secondly the universities for their incredibly lax assessment and training of postgraduate students; thirdly the authors, who are usually dupes of their own'1 processes, for rushing into print without consult!ng the best scholars In their field. Ehrstine shows his lack of scholarship on the first two pages of his book; thereafter he has an uphill tattle!1n convincing the reader that he has some special insights Which compensate foKtfris, once fashionable, disability. -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

Neville 12/16/1968 a PROPHECY in His Poem Called "Europe," Which Is

Neville 12/16/1968 A PROPHECY In his poem called "Europe," which is a prophecy about you, William Blake said: "Then Enitharmon woke, nor knew that she had slept, and eighteen hundred years were fled as if they had not been." Told in the form of a story, Blake used the name "Enitharmon" to express any emanating desire or image. Enitharmon is the emanation of Los, who - in the story - had the similitude of the Lord and all imagination. Entering into his image (his Enitharmon), Los dreams it into reality; and when he awoke he knew not that he had slept, yet eighteen hundred years had fled. In my case, 1,959 years had fled as though they had not been. And I had no idea I had entered into an image called Neville and made it real. But I, all imagination, so loved the shadow I had cast, I entered into it and made it alive. To those in immortality I seemed to be as one sleeping on a couch of gold, but to myself I was a wanderer. Although lost in dreary night, I kept the divine vision in time of trouble. I kept on dreaming I was Neville until I awoke, not knowing I had slept; yet 1,959 years had fled as though they had not been. Blake tells us that in the beginning we were all united with God in a death like his. Then we heard the story and entered into our shadows. Now, a shadow is a representation, either in painting or drama, in distinction from the reality portrayed. -

The Prophetic Books of William Blake : Milton

W. BLAKE'S MILTON TED I3Y A. G.B.RUSSELL and E.R.D. MACLAGAN J MILTON UNIFORM WirH THIS BOOK The Prophetic Books of W. Blake JERUSALEM Edited by E. R. D. Maclagan and A. G. B. Russell 6s. net : THE PROPHETIC BOOKS OF WILLIAM BLAKE MILTON Edited by E. R. D. MACLAGAN and A. G. B. RUSSELL LONDON A. H. BULLEN 47, GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1907 CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. INTRODUCTION. WHEN, in a letter to his friend George Cumberland, written just a year before his departure to Felpham, Blake lightly mentions that he had passed " nearly twenty years in ups and downs " since his first embarkation upon " the ocean of business," he is simply referring to the anxiety with which he had been continually harassed in regard to the means of life. He gives no hint of the terrible mental conflict with which his life was at that time darkened. It was more actually then a question of the exist- ence of his body than of the state of his soul. It is not until several years later that he permits us to realize the full significance of this sombre period in the process of his spiritual development. The new burst of intelle6tual vision, accompanying his visit to the Truchsessian Pi6lure Gallery in 1804, when all the joy and enthusiasm which had inspired the creations of his youth once more returned to him, gave him courage for the first time to face the past and to refledl upon the course of his deadly struggle with " that spe6lrous fiend " who had formerly waged war upon his imagination. -

William Sears, Thief in the Night

Thief in the Night or The Strange Case of the Missing Millennium by William Sears George Ronald Oxford, England First edition 1961 “But the day of the Lord will come as a thief in the night; in which the heavens shall pass away with a great noise, and the elements shall melt with fervent heat, the earth also and the works that are therein shall be burnt up.” II Peter 3:10 The Problem. In the first half of the nineteenth century, there was world- wide and fervent expectation that during the 1840’s the return of Christ would take place. The story made the headlines and even reached the Congress of the United States. From China and the Middle East to Europe and America, men of conflicting ideas shared in the expectancy. Scoffers were many but the enthusiasm was tremendous, and all agreed on the time. Why? And what became of the story? Did anything happen or was it all a dream? The Solution. Patiently, and with exemplary thoroughness, William Sears set out to solve this mystery. In Thief in the Night he presents his fully detailed “conduct of the case” in an easy style which enthuses the reader with the excitement of the chase. The solution to which all the clues lead comes as a tremendous challenge. This is a mystery story with a difference: the mystery is a real one, and of vital importance to every human being. The author presents the evidence in The case of the missing millennium in such a way that you can solve it for yourself. -

Year 8 Spring Term English School Booklet

Module 2 Year 8: Romantic Poetry Songs of Innocence and Experience, William Blake Name: Teacher: 1 The Industrial Revolution Industrial An industrial system or product is one that He rejected all items made using industrial (adjective) uses machinery, usually on a large scale. methods. Natural Natural things exist or occur in nature and She appreciated the natural world when she left (adjective) are not made or caused by people. the chaos of London. William Blake lived from 28 November 1757 until 12 August 1827. At this time, Britain was undergoing huge change, mainly because of the growth of the British Empire and the start of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was a time when factories began to be built and the country changed forever. The countryside, natural and rural settings were particularly threatened and many people did not believe they were important anymore because they wanted the money and the jobs in the city. The population of Britain grew rapidly during this period, from around 5 million people in 1700 to nearly 9 million by 1801. Many people left the countryside to seek out new job opportunities in nearby towns and cities. Others arrived from further away: from rural areas in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, for example, and from across large areas of continental Europe. As cities expanded, they grew into centres of pollution and poverty. There were good things about the Industrial Revolution, but not for the average person – the rich factory owners and international traders began to make huge sums of money, and the gap between rich and poor began to widen as a result. -

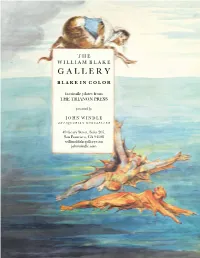

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake Author(s): PAUL MINER Source: Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Winter 1962), pp. 59-73 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23091046 Accessed: 20-06-2016 19:39 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 19:39:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAUL MINER* r" The TygerGenesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake There is the Cave, the Rock, the Tree, the Lake of Udan Adan, The Forest and the Marsh and the Pits of bitumen deadly, The Rocks of solid fire, the Ice valleys, the Plains Of burning sand, the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire, The Islands of the fiery Lakes, the Trees of Malice, Revenge And black Anxiety, and the Cities of the Salamandrine men, (But whatever is visible to the Generated Man Is a Creation of mercy & love from the Satanic Void). (Jerusalem) One of the great poetic structures of the eighteenth century is William Blake's "The Tyger," a profound experiment in form and idea. -

Norma Greco the Problematic Vision of Blake's Innocence: a View from Night Approaches to William Blake' S "Night" Typi

Norma Greco The Problematic Vision of Blake's Innocence: A View From Night Approaches to William Blake' s "Night" typify the larger critical view of Blake's Songs of Innocence as admirably accepting of Christian faith and fortitude.' Despite intrusions of danger and death into the pastoral sanctity of "Night," most critics have read the song ultimately as a proclamation of the essential hannony, if not expressly Christian character, of Blake's "state" of Inno.cence? D. G. Gillham, for example, sees the poem's speaker as one who has a "knowledge" of "real" love which is "at the centre of the poem" (239-40), while for E. D. Hirsch "Night," like Innocence, reveals a "radically immanental Christianity" (29) and a "religious affinnation" (28). Although many critics perceive the song's darker elements and note, as does Harold Bloom, its "gentle irony" (41), they avoid or palliate the speaker's easy religious resolution to the poem's spiritual dilemma. Like others who sense ambiguities in "Night," Zachary Leader resolves tensions within an optimistic and transcendent Christian framework, identifying Innocence with religious faith in the midst of adversity: As the speaker seeks out his nest, his meditations upon the night move from a sense of calm and soothing benevolence (the activities of the angels in stanzas 1 to 3) to an acknowledgement of danger and suffering .... The initial mood of calm acceptance lives on in stanza 4, ·and we feel that night's soothing influence prevents him from becoming frightened or despairing. Though the angels are THE PROBLEMATIC VISION OF BLAKE'S INNOCENCE 41 ineffectual, the speaker is himself still subject to the soothing spell of night, which is why he continues to speak of the angels, its visionary form, as "most heedful." He has no clear understanding of how their benevolent protection works .. -

The Metaphysical Grounds of Oppression in Blake's Visions of the Daughters of Albion

Colby Quarterly Volume 20 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 1984 The Metaphysical Grounds of Oppression in Blake's Visions of the Daughters of Albion Mark Bracher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 20, no.3, September 1984, p.164-176 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Bracher: The Metaphysical Grounds of Oppression in Blake's Visions of the The Metaphysical Grounds of Oppression in Blake's Visions of the Daughters of Albion by MARK BRACHER T IS generally recognized that the central doctrine of Blake's thought, I in many ways, is the sovereignty of the individual. And it is also generally recognized that virtually all of Blake's poetry is an attempt to free individuals from the "mind forg'd manacles" that prevent them from exercising their sovereignty-mind-forg'd manacles being the pro scriptive legal and moral codes which fetter desire and imagination. What is not so generally understood, however, is the way in which, in Blake's view, these legal and moral fetters are themselves the result of restricted metaphysical perspectives-perspectives which glimpse part of existence and fancy that the whole. Since (to paraphrase Blake's observation in The Marriage ofHeaven and Hell) everything we see is owing to our metaphysics, every action and feeling, every goal and desire that we have is ultimately grounded in and conditioned by our most fundamental metaphysical assumptions assumptions which are usually only tacitly or unconsciously held. -

![The [First] Book of Urizen](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2930/the-first-book-of-urizen-3092930.webp)

The [First] Book of Urizen

The [First] Book of Urizen (Engraved 1794) Preludium to the First Book of Urizen Of the primeval Priest’s assum’d power, When Eternals spurn’d back his Religion, And gave him a place in the North, Obscure, shadowy, void, solitary. Eternals! I hear your call gladly. Dictate swift wingèd words, and fear not To unfold your dark visions of torment. CHAP. I 1. LO, a Shadow of horror is risen In Eternity! unknown, unprolific, Self-clos’d, all-repelling. What Demon Hath form’d this abominable Void, This soul-shudd’ring Vacuum? Some said 5 It is Urizen. But unknown, abstracted, Brooding, secret, the dark Power hid. 2. Times on times he divided, and measur’d Space by space in his ninefold darkness, Unseen, unknown; changes appear’d 10 Like desolate mountains, rifted furious By the black winds of perturbation. 3. For he strove in battles dire, In unseen conflictions with Shapes, Bred from his forsaken wilderness, 15 Of beast, bird, fish, serpent, and element, Combustion, blast, vapour, and cloud. 4. Dark, revolving in silent activity, Unseen in tormenting passions, An Activity unknown and horrible, 20 A self-contemplating Shadow, In enormous labours occupièd. Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/engl404 Saylor.org This resource is in the public domain. Page 1 of 14 5. But Eternals beheld his vast forests; Ages on ages he lay, clos’d, unknown, Brooding, shut in the deep; all avoid 25 The petrific, abominable Chaos. 6. His cold horrors, silent, dark Urizen Prepar’d; his ten thousands of thunders, Rang’d in gloom’d array, stretch out across The dread world; and the rolling of wheels, 30 As of swelling seas, sound in his clouds, In his hills of stor’d snows, in his mountains Of hail and ice; voices of terror Are heard, like thunders of autumn, When the cloud blazes over the harvests.