Liability in Professional Baseball and Hockey for Spectator Injuries Sustained During the Course of the Game Christopher T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In an Effort to Standardize Ringette Line Markings Across the Country, the CRFC Has Worked in Consultation with Ringette Canada

In an effort to standardize ringette line markings across the country, the CRFC has worked in consultation with Ringette Canada on how best to layout a ringette ice sheet. The CRFC supports the revised layout and encourages facility managers to consider the benefits of conforming to these layout guidelines whenever possible. New construction and/or retrofits to a facility should give consideration to these measurements, however, other ice sport marking requirements should be overlayed prior to making any changes so that all ice sports are given the same consideration. The following drawings are offered as a support tool for ice technicians to your planning and annual ice painting activities. As ice markings may change at any time, be reminded of the importance for you to annually recheck all local and regional ice sport marking requirements prior to undertaking the ice painting task! VERSION 2013-7 CRFC - RINGETTE CANADA LINE MARKINGS Ice rinks that offer the sport of Ringette will be required to install additional painted/fabric markings. Ringette utilizes most of the standard Hockey Canada (HC) ice hockey markings with additional free pass dots in each of the attacking zones and centre zone areas as well as a larger defined crease area. Two (2) additonal free play lines (1 in each attacking zone) are also required. Free Play Lines In both attacking zones located above the 30 ft. (9.14 m) circles is a 5.08 cm (2 in.) red “Free Play Line”. These lines shall be installed to completely overlap the top of each of the 30 ft. circles. -

The Effectiveness of Mouth Guards and Face Masks in Reducing Facial and Oral Injury in Ice Hockey Players

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MOUTH GUARDS AND FACE MASKS IN REDUCING FACIAL AND ORAL INJURY IN ICE HOCKEY PLAYERS ABSTRACT Purpose: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use and the effect of mouth guards and face masks in minimizing the number and severity of concussions and dental injuries in male hockey players; discuss the use of mouth guards in orthodontic wearers; and determine guidelines for the wear and replacement of mouth guards and face masks by junior hockey players. Methods: Data was compiled from scientific research papers published in medical and dental journals dating from 1998 through 2003, information provided through the Canadian and American Dental Associations, and the collaborative findings of sports medicine and sports dental practitioners actively involved in both minor and national hockey leagues. Results: The use of mouth guards and face masks helps prevent and minimize the extent of concussions and dental injuries in male hockey players, especially in players wearing orthodontic equipment such as braces. Maximal protection occurs when a mouth guard is used in conjunction with a face mask. Several different types of mouth guards are currently available; the choice of material and construction affects the protective ability, comfort, and durability of these various mouth guards. Conclusion: Mouth guards and face masks are strongly recommended to minimize the number and severity of concussions and dental injuries in hockey players. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Mouth guards Why wear a mouth guard? ° A hockey puck can -

INTERNATIONAL HOCKEY FEDERATION Multi-Sports Areas Gen 2 Maximising Sporting Opportunities

INTERNATIONAL HOCKEY FEDERATION multi-sports areas Gen 2 maximising sporting opportunities Web fih.ch/facilities Email [email protected] Hockey is the world’s third most popular team sport. Unfortunately, there is not a single type of synthetic Fast, technically skilful, and requiring good levels of turf that meets the needs of every sport. Small or large personal fitness, the sport is renowned for its social ball, contact or non-contact sport, high grip or low foot inclusiveness, gender equality, and ability to attract grip; all these factors affect how players rate a surface. and engage with players for many years. Finding the right compromises is key to success. With an innovative approach to improving the game, The GEN 2 concept shows how surfaces designed for hockey recognises the benefits synthetic turf surfaces hockey, can also be used by other sports. offer, and embraces their use at all levels of the game. Creating opportunities for people to discover and play hockey is often difficult. For some, the challenge is providing suitable areas to play, for others, ensuring facilities are sustainable is key to their long-term success. Many sports face these challenges, and this is making the concept of multi-sports fields increasingly attractive; sharing facilities and maximising opportunities is often the best way to secure investment. Community and school hockey is best played on 2G synthetic turf. Unlike longer pile turfs, the short dense pile of a 2G surface allows a hockey ball to travel quickly and predictably across the surface; just what the players want. By laying the correct shockpad under the 2G synthetic turf, you can also provide a great playing surface for community level: • Futsal • Soccer • Tennis • Netball • Lacrosse • Softball • Athletics training / jogging tracks Outdoors, the are two versions of hockey Hockey – played by two teams, each with 11 players on a full-size field Hockey5s - played by two teams, each with 5 players 2G synthetic turf surfaces on a court. -

WHY: to Spend a Week of Bandy & Hockey Training And

LEADERS: Steve Jecha and several In October 2018 the MPLS Storm will WHY: To spend a week of Bandy & coaches and parents to be named later. take a group to Sweden for a one week Hockey training and competition in Steve Jecha played four years of college trip over MEA weekend. Västerås, Sweden. hockey and 20+ years of international level bandy in Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Parents are welcome and encouraged to In addition to on ice training there will be Russia. come, but it is not mandatory as we have off ice activities, including visits to taken kids without parents on six prior schools, social time with local Swedish COST: To Be Determined, but trips with no issues. We will bring no youth, touring the town and region, plus a estimated at $1,850*. This includes more than 35 players (boys & girls). More day to visit and learn about Stockholm. In airfare, transportation from Stockholm details are as follows: the past, we have played Airport to Västerås and back, vans, Innebandy/Floorball, gone to a Professional lodging, ice time and breakfasts. WHO: Boys or Girls in the Hockey Game, and professional bandy and approximate age category of 11 - 15. innebandy games. All are dependent on LODGING: We typically stay at the Best While the trip is a MPLS Storm Trip, their game schedules and what can be Western Hotel Esplanade in kids/friends from other associations are arranged. Vasteras city center. welcome. Invite them if they are interested in more info. FOOD: Breakfasts are provided. Lunch & Dinners will be at local WHEN: October 16-24, 2018. -

Field Hockey

Field Hockey Fall 2020 General Information Every school district/program should consult with their local health department to determine which risk level to start this program safely. Continued consultation with local health department should be used to determine when progression to the next risk level can be initiated. This document is to be utilized in compliance with all EEA, DESE and DPH guidelines in place. Pre-Workout/Pre-Contest Screening: Athletes and coaches may not attend practices or games if they are isolated for illness or quarantined for exposure to infection. Prior to attending practices or games, athletes and coaches should check their temperature. If a student-athlete or a coaching staff member has a temperature of 100 degrees or above, they should not attend practices or games. Likewise if they have any other symptoms of COVID-19 infection (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html), they should not attend practices or games. Student-athletes and coaches who have symptoms of COVID19 infection should follow DPH guidance regarding isolation and testing. For students with symptoms who test negative for COVID-19 infection, they may return to sport once they are approved to return to school (when afebrile for 24 hours and symptomatically improved). Student athletes and coaches who are diagnosed with COVID-19 infection may return to school once they have been afebrile for 24 hours and with improvement in respiratory symptoms, and once ten days have passed since symptoms first appeared, according to DPH guidelines. In addition, persons with COVID19 infection need to receive written clearance from their health care provider in order to return to sport. -

2018 FRISCO ROUGHRIDERS MEDIA GUIDE Designed, Written and Laid out by Ryan Rouillard

table of contents CLUB INFORMATION club history & records Front office directory .................................. 4-5 Year-by-year records ......................................46 Ownership &and executive bios ............... 6-8 Year-by-year statistics ...................................47 Club information ..............................................9 RoughRiders timeline ..............................48-55 Dr Pepper Ballpark ...................................10-11 Single-game team records ...........................56 Texas League All-Star Games in Frisco .......12 Single-game individual records ..................57 Broadcasters, broadcast partners ...............13 Single-season team batting records ..........58 Media information and policies ..................14 Single-season team pitching records .........59 Rangers Minor League info ....................15-17 Single-season individual batting records ......60 Single-season individual pitching records ....61 COACHES & STAFF Career batting records ..................................62 Joe Mikulik (manager) .............................20-21 Career pitching records ................................63 Greg Hibbard (pitching coach) ....................22 Notable streaks...............................................64 Jason Hart (hitting coach) ............................23 Perfect games and no-hitters ......................65 Support staff, coaching awards ...................24 Opening Day lineups .....................................66 Midseason All-Stars, Futures Game ............67 -

Central Missouri, University of Vendor List

Central Missouri, University of Vendor List 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1052415 Standard Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1052556 Standard Effective Products: Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Tote Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - Travel Bag Automobile Items - Ice Scraper Automobile Items - Key Tag/Chain Crew Sweatshirt - Fleece Crew Domestics - Table Cover Domestics - Cloth 10/08/2019 Page 1 of 88 Domestics - Beach Towel Electronics - Flash Drive Electronics - Earbuds Furniture/Furnishings - Picture Frame Furniture/Furnishings - Screwdriver Furniture/Furnishings - Multi Tool Games - Bean Bag Toss Game Games - Playing Cards Garden Accessories - Seed Packet Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties -

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 10/21/2019 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

2018 MEDIA GUIDE Bios Player 2018 Review Season 2017 Fire Records Frogs Opponents |

front officefront | 2018 manager & staff & manager 2018 | atlanta braves atlanta | MEDIA GUIDE MEDIA 2018 player bios player 2018 | 2018 2017 season review season 2017 | 2018 florida fire mediaguide frogs florida 2018 fire records frogs | opponents | | 1 Miscellaneous Front officeFront TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office Fire Frogs Records Front Office Directory 3 All-Time Roster 78 Staff Bios 4-6 Single-Season Highs and Low 79 Single-Season Individual Records 80 | 2018 Manager & Staff The Last Time It Happened... 81 2018 manager & staff & manager 2018 Manager and Coaches 8 Yearly Batting Leaders 82 Training Staff 9 Yearly Pitching Leaders 83 Career Batting Leaders 84 Atlanta Braves Career Pitching Leaders 85 Atlanta Braves Directory 11 Year-By-Year Miscellaneous 86-87 Pl ayer Development, Scouting and Minor League Staff 12 Fire Frogs Daily History 88-94 Atlanta Braves 13 | Gwinnett Stripers (Triple-A) 14-15 Opponents atlanta braves atlanta Mississippi Braves (Double-A) 16-17 Florida State League Directory 97 Florida Fire Frogs (Advanced-A) 18-19 Florida State League Hall of Fame 99 Rome Braves (Low-A) 20-21 Bradenton Marauders 100 Danville Braves (Rookie) 22-23 Charlotte Stone Crabs 101 Gulf Coast League Braves (Rookie) 24 Clearwater Threshers 102 Dominican Summer League Braves (Rookie) 24 Daytona Tortugas 103 2017 Award Winners 25 Dunedin Blue Jays 104 | 2017 Pitching and Batting Leaders 26-27 Fort Myers Miracle 105 2018 Player bios Player 2018 2017 First-Year Player Draft 28 Jupiter Hammerheads 106 2018 Top Prospects 29 Lakeland Flying -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, December 17, 2015 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, December 17, 2015 Braves.com Braves make deal with catcher Flowers official By Mark Bowman / MLB.com | @mlbbowman | December 16th, 2015 ATLANTA -- Immediately after being non-tendered by the White Sox two weeks ago, Atlanta-area native Tyler Flowers began looking forward to a potential homecoming. The veteran catcher received his wish last week when he and the Braves agreed to a two-year, $5.3 million contract. The Braves officially announced the completion of the deal on Wednesday afternoon. Outfielder Dian Toscano was outrighted to Triple-A Gwinnett to create a spot on the 40-man roster for Flowers, who is now set to share the Braves' catching duties with his former White Sox teammate A.J. Pierzynski. "This turned out maybe even better than I had hoped," Flowers said. "Atlanta is home to me, and the [Braves] organization is somewhat home to me as well. When I was non-tendered, I was hoping the Braves would be interested because I knew I would love an opportunity to return." After being born and raised in suburban Atlanta, Flowers experienced the thrill of being selected by his hometown team in the 33rd round of the 2005 Draft. The 6-foot-4, 245-pound catcher steadily enhanced his stock during the three seasons he played in Atlanta's farm system. He was one of the key pieces the Braves used to acquire Javier Vazquez from the White Sox on Dec. 4, 2008. With the addition of Flowers, the Braves have gained an opportunity to lessen the workload placed on the 38-year-old Pierzynski, who logged 104 starts as Atlanta's catcher this year. -

Houston, University of Vendor List

Houston, University of Vendor List 4imprint, Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Number Type Status Contracts: 982284 Internal Usage Effective 985389 Standard Effective 999077 Clear Lake Marks Effective 999078 Downtown Marks Effective 999079 Victoria Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Tote Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - Travel Bag Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties - Koozie Gifts & Novelties - Lanyards Gifts & Novelties - tire gauge Gifts & Novelties - Rally Towel Home & Office - Fleece Blanket Home & Office - Dry Erase Sheets Home & Office - Night Light Home & Office - Mug Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Pencil Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Pen Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Notepad Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Desk Calendar Paper, Printing, & Publishing - Portfolio Specialty Items - Mouse Pad Specialty Items - Dental Floss Specialty Items - Sunscreen Specialty Items - Lip Balm Specialty Items - Massager Sporting Goods & Toys - Sports Bottle Sporting Goods & Toys - Chair-Outdoor Sporting Goods & Toys - Balloon Sporting Goods & Toys - Flashlight Sporting Goods & Toys - Frisbee Sporting Goods & Toys - Hula Hoop Sporting Goods & Toys - Pedometer T-Shirts - T shirt Womens Apparel - Fleece Vest 11/08/2013 Page 1 of 123 5th & Ocean Clothing Contact: Marla Sojo 305-822-4606 x206 590 West 83rd St Hialeah, FL 33014 [email protected] -

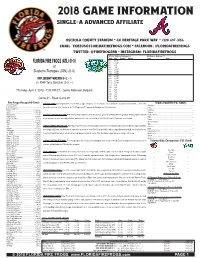

2018 Game Information Single-A Advanced Affiliate

2018 game information single-a advanced affiliate osceola county stadium • 631 heritage park way • (321) 697-3156 email: [email protected] • facebook: /floridafirefrogs twitter: @firefrogsbb • instagram: floridafirefrogs 2018 vs. Daytona Tortugas: 0-0 All-Time vs. Daytona: 7-7 Date Site Result Winner Loser Save FLORIDA FIRE FROGS (ATL) (0-0) 4/5 at DBT 4/6 at DBT 4/7 FLO at 4/8 FLO 4/23 at DBT Daytona Tortugas (CIN) (0-0) 4/24 at DBT 4/25 at DBT 6/21 at DBT RHp Jeremy Walker (0-0, --) 6/22 at DBT 6/23 at DBT vs. RHP Tony Santillan (0-0, --) 6/24 at DBT 6/29 FLO 6/30 FLO 7/1 FLO Thursday, April 5, 2018 - 7:05 PM ET - Jackie Robinson Ballpark 7/9 FLO 7/10 FLO 7/11 FLO Game #1 - Road Game #1 7/12 FLO Fire Frogs Recap (All-Time) TODAY’S GAME: Opening day in the Florida State League and game one of a 4 game series split between Daytona and Kissimmee. This is the TEAM LEADERS (FSL RANK) Current Streak ..................................................-- Average .................................................................... -- Last 5 Games ...................................................-- first of five series in 2018. Last year, the Fire Frogs went 7-7 against the Tortugas and 2-5 in Daytona. Hits ........................................................................... -- Last 10 Games .................................................-- Home .................................................... --(25-34) Doubles .................................................................... -- Away ....................................................